Parliament of 1327

The Parliament of 1327, which sat at the Palace of Westminster between 7 January and 9 March 1327, was instrumental in the transfer of the English Crown from King Edward II to his son, Edward III. Edward II had become increasingly unpopular with the English nobility due to the excessive influence of unpopular court favourites, the patronage he accorded them, and his perceived ill-treatment of the nobility. By 1325, even his wife, Queen Isabella, despised him. Towards the end of the year, she took the young Edward to her native France, where she entered into an alliance with the powerful and wealthy nobleman Roger Mortimer, who her husband previously had exiled. The following year, they invaded England to depose Edward II. Almost immediately, the King's resistance was beset by betrayal, and he eventually abandoned London and fled west, probably to raise an army in Wales or Ireland. He was soon captured and imprisoned.

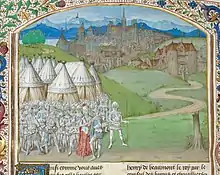

Isabella and Mortimer summoned a parliament to confer legitimacy on their regime. The meeting began gathering at Westminster on 7 January, but little could be done in the absence of the King. The fourteen-year-old Edward was proclaimed "Keeper of the Realm" (but not yet king), and a parliamentary deputation was sent to Edward II asking him to allow himself to be brought to parliament. He refused, and the parliament continued without him. The King was accused of offences ranging from the promotion of favourites to the destruction of the church, resulting in a betrayal of his coronation oath to the people. These were known as the "Articles of Accusation". The City of London was particularly aggressive in its attacks on Edward II, and its citizens may have helped intimidate those attending the parliament into agreeing to the King's deposition, which occurred on the afternoon of 13 January.

On or around 21 January, the Lords Temporal sent another delegation to the King to inform him of his deposition, effectively giving Edward an ultimatum: if he did not agree to hand over the crown to his son, then the lords in parliament would give it to somebody outside the royal family. King Edward wept but agreed to their conditions. The delegation returned to London, and Edward III was proclaimed king immediately. He was crowned on 1 February 1327. In the aftermath of the parliamentary session, his father remained imprisoned, being moved around to prevent attempted rescues; he died—presumed killed, probably on Mortimer's orders—that September. Crises continued for Mortimer and Isabella, who were de facto rulers of the country, partly because of Mortimer's own greed, mismanagement, and mishandling of the new king. Edward III led a coup d'état against Mortimer in 1330, overthrew him, and began his personal rule.

Background

King Edward II of England had court favourites who were unpopular with his nobility, such as Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger. Gaveston was killed during an earlier noble rebellion against Edward in 1312, and Despenser was hated by the English nobility.[1] Edward was also unpopular with the common people due to his repeated demands from them for unpaid military service in Scotland.[2] None of his campaigns there were successful,[3] and this led to a further decline in his popularity, particularly with the nobility. His image was further diminished in 1322 when he executed his cousin, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, and confiscated the Lancaster estates.[4] Historian Chris Given-Wilson has written how by 1325 the nobility believed that "no landholder could feel safe" under the regime.[5] This distrust of Edward was shared by his wife, Isabella of France,[6][note 1] who believed Despenser responsible for poisoning the King's mind against her.[9] In September 1324 Queen Isabella had been publicly humiliated when the government declared her an enemy alien,[10] and the King had immediately repossessed her estates,[10] probably at the urging of Despenser.[11] Edward also disbanded her retinue.[12] Edward had already been threatened with deposition on two previous occasions (in 1310 and 1321).[9] Historians agree that hostility towards Edward was universal. W. H. Dunham and C. T. Wood ascribed this to Edward's "cruelty and personal faults",[13] suggesting that "very few, not even his half-brothers or his son, seemed to care about the wretched man"[13] and that none would fight for him.[13] A contemporary chronicler described Edward as rex inutilis, or a "useless king".[14]

France had recently invaded the Duchy of Aquitaine,[11] then an English royal possession.[9] In response, King Edward sent Isabella to Paris, accompanied by their thirteen-year-old son, Edward, to negotiate a settlement.[9] Contemporaries believed she had sworn, on leaving, never to return to England with the Despensers in power.[11] Soon after her arrival, correspondence between Isabella and her husband, as well between them and her brother King Charles IV of France and Pope John XXII, effectively disclosed the royal couple's increasing estrangement to the world.[9] A contemporary chronicler reports how Isabella and Edward became increasingly scathing of each other,[15] worsening relations.[9] By December 1325 she had entered into a possibly sexual relationship in Paris with the wealthy exiled nobleman Roger Mortimer.[9] This was public knowledge in England by March 1326,[11] and the King openly considered a divorce.[note 2] He demanded that Isabella and Edward return to England, which they refused to do:[9] "she sent back many of her retinue but gave trivial excuses for not returning herself" noted her biographer, John Parsons.[11] Their son's failure to break with his mother angered the King further.[15][note 3] Isabella became more strident in her criticisms of Edward's government, particularly against Walter de Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter, a close associate of the King and Despenser.[17] King Edward alienated his son by putting the prince's estates under royal administration in January 1326, and the following month the King ordered that both he and his mother be arrested on landing in England.[19]

While in Paris, the Queen became the head of King Edward's exiled opposition. Along with Mortimer, this group included Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent,[20] Henry de Beaumont, John de Botetourt, John Maltravers and William Trussell.[21] All were united by hatred of the Despensers.[22] Isabella portrayed her and Prince Edward as seeking refuge from her husband and his court, both of whom she claimed were hostile to her, and claimed protection from Edward II.[23] King Charles refused to countenance an invasion of England; instead, the rebels gained the Count of Hainaut's backing. In return, Isabella agreed that her son would marry the Count's daughter Philippa.[21][24] This was a further insult to Edward II, who had intended to use his eldest son's marriage as a bargaining tool against France, probably intending a marriage alliance with Spain.[25]

Invasion of England

.svg.png.webp)

From February 1326 it was clear in England that Isabella and Mortimer intended to invade. Despite false alarms,[note 4] large ships, as a defensive measure, were forbidden from leaving English ports, and some were pressed into royal service. King Edward declared war on France in July; Isabella and Mortimer invaded England in September, landing in Suffolk on the 24th.[28] The commander of the royal fleet assisted the rebels: the first of many betrayals Edward II suffered.[29] Isabella and Mortimer soon found they had significant support among the English political class. They were quickly joined by Thomas, Earl of Norfolk, the King's brother, accompanied by Henry, Earl of Leicester (brother of the executed Earl of Lancaster), and soon afterwards arrived the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishops of Hereford and Lincoln.[11][note 5] Within the week, support for the King had dissolved, and, accompanied by Despenser, he deserted London and travelled west.[31][note 6] Edward's flight to the west precipitated his downfall.[32] Historian Michael Prestwich describes the King's support as collapsing "like a building hit by an earthquake". Edward's rule was already weak, and "even before the invasion, along with preparation, there had been panic. Now there was simply panic".[21] Ormrod notes how

Given that Mortimer and his adherents were already condemned traitors and that any engagement with the invading force was to be treated as an act of open rebellion, it is all the more striking how many great men were prepared to enter upon such a high-risk venture at so early a stage in its prosecution. In this respect at least the presence of the heir to the throne in the queen's entourage may have proved decisive.[33]

King Edward's attempt to raise an army in South Wales was to no avail, and he and Despenser were captured on 16 November 1326 near Llantrisant.[9] This, along with the unexpected swiftness with which the entire regime had collapsed, forced Isabella and Mortimer to wield executive power until they made arrangements for a successor to the throne.[34] The King was incarcerated by the Earl of Leicester, while those suspected of being Despenser spies[35] or supporters of the King[9]—particularly in London, which was aggressively loyal to the Queen[36]—were murdered by mobs.[9][note 7]

Isabella spent the last months of 1326 in the West Country, and while in Bristol witnessed the hanging of Despenser's father, the Earl of Winchester on 27 October. Despenser himself was captured in Hereford and executed there within the month.[9] In Bristol Isabella, Mortimer and the accompanying lords discussed strategy.[45][note 8] Not yet possessing the Great Seal, on 26 October they proclaimed the young Edward guardian of the realm,[9] declaring that "by the assent of the whole community of the said kingdom present there, they unanimously chose [Edward III] as keeper of the said kingdom". He was not yet officially declared king.[47] The rebels' description of themselves as a community deliberately harked back to the reform movement of Simon de Montfort and the baronial league, which had described its reform programme as being of the community of the realm against Henry III.[48] Claire Valente has pointed out how, in reality, the most common phrase heard "was not 'the community of the realm', but 'the quarrel of the earl of Lancaster'", illustrating how the struggle was still a factional one within baronial politics, whatever cloak it may have appeared to possess as a reform movement.[49]

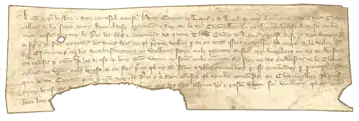

By 20 November 1326 the Bishop of Hereford had retrieved the Great Seal from the King,[50] and delivered it to the King's son. He could now be announced as his father's heir apparent.[9] Although, at this stage, it might still have been possible for Edward II to remain king, says Ormrod, "the writing was on the wall".[51] A document issued by Isabella and her son at this time described their respective positions thus:

Isabel by the grace of God Queen of England, lady of Ireland, Countess of Ponthieu and we, Edward, eldest son of the noble King Edward of England, Duke of Gascony, Earl of Chester, of Ponthieu, of Montreuil...[34]

— TNA SC 1/37/46.

Summoning of parliament

Isabella, Mortimer and the lords arrived in London on 4 January 1327.[50] In response to the previous year's spate of murders, Londoners had been forbidden to bear arms, and two days later all citizens had sworn an oath to keep the peace.[52] Parliament met on 7 January to consider the state of the realm now the King was incarcerated. It had originally been summoned by Isabella and the Prince, in the name of the King, on 28 October the previous year. Parliament had been intended to assemble on 14 December 1326, but on 3 December—still in the name of the King[note 9]—further writs were issued deferring the sitting until early the next year. This, it was implied, was due to the King being abroad, rather than imprisoned.[9] Because of this, parliament would have to be held before the Queen and Prince Edward.[54] The History of Parliament Trust has described the legality of the writs as being "highly questionable",[9] and C. T. Wood called the sitting "a show of pseudo-parliamentary regularity",[55][note 10] "stage-managed" by Mortimer and Thomas, Lord Wake.[56] For Isabella and Mortimer, governing through parliament was only a temporary solution to a constitutional problem, because at some point their positions would likely be challenged legally.[50] Thus, suggests Ormrod, they had to enforce a solution favourable to Mortimer and the Queen, by any means they could.[54]

Contemporaries were uncertain as to the legality of Isabella's parliament.[13] Edward II was still king, although in official documents, this was only alongside his "most beloved consort Isabella queen of England" and his "firstborn son keeper of the kingdom",[57] in what Phil Bradford called as a "nominal presidency".[58] King Edward was said to be abroad when in reality he was imprisoned in Kenilworth Castle. It was maintained that he desired a "colloquium" and a "tractatum" (conference and consultation)[57] with his lords "upon various affairs touching himself and the state of his kingdom", hence the holding of parliament. Supposedly it was Edward II himself who postponed the first sitting until January, "for certain necessary causes and utilities", presumably at the behest of the Queen and Mortimer.[9]

A priority for the new regime was deciding what to do with Edward II. Mortimer considered holding a state trial for treason, in the expectation of a guilty verdict and a death sentence. He and other lords discussed the matter at Isabella's Wallingford Castle just after Christmas, but with no agreement. The Lords Temporal affirmed that Edward had failed his country so gravely that only his death could heal it; the attending bishops, on the other hand, held that whatever his faults, he had been anointed king by God. This presented Isabella and Mortimer with two problems. First, the bishops' argument would be popularly understood as risking the wrath of God. Second, public trials always bring the danger of an unintended verdict, particularly as it seems likely a broad body of public opinion doubted whether an anointed king could even commit treason. Such a result would mean not only Edward's release but his restoration to the throne. Mortimer and Isabella sought to avoid a trial and yet keep Edward II imprisoned for life.[59][note 11] The King's imprisonment (officially by his son) had become public knowledge, and Isabella's and Mortimer's hand was forced as the arguments for the young Edward being named keeper of the kingdom were now groundless (as the King had clearly returned to his realm—one way or another).[60]

Attendance

Although the deposition of Edward II did not attack kingship itself, the actual process of deposing a legitimate and anointed king involved an attempt to square the circle. That process had taken place during, in, on the margins of, and outside an assembly whose own legitimacy was, to say the least, doubtful.[61]

No parliament had sat since November 1325.[62] Only 26 of the 46 barons who had been summoned in October 1326 for the December parliament were then also summoned to that of January 1327, and six of those had never received summonses under Edward II at all.[63] Officially, the instigators of the parliament were the Bishops of Hereford and Winchester, Roger Mortimer and Thomas Wake; Isabella almost certainly played a background role.[64] They summoned, as Lords Spiritual, the Archbishop of Canterbury and fifteen English and four Welsh bishops as well as nineteen abbots. The Lords Temporal were represented by the Earls of Norfolk, Kent, Lancaster, Surrey, Oxford, Atholl and Hereford. Forty-seven barons, twenty-three royal justices, and several knights and burgesses were summoned from the shires[9] and the Cinque Ports.[50] They may well have been encouraged, suggests Maddicott, by the wages to be paid to those attending: the "handsome sum" of four shillings a day for a knight and two for a burgess.[65][note 12] The knights provided the bulk of Isabella's and the Prince's vocal support; they included Mortimer's sons, Edward, Roger and John.[66] Sir William Trussell was appointed procurator, or Speaker,[67] despite his not being an elected member of parliament.[56] Although the office of procurator was not new, the purpose of Trussell's role set a constitutional precedent, as he was authorised to speak on behalf of parliament as a body.[68] A chronicle describes Trussell as one "who cannot disagree with himself and, [therefore], shall ordain for all".[67] There were fewer lords present than were traditionally summoned, which increased the influence of the Commons.[62][note 13] This may have been a deliberate strategy on behalf of Isabella and Mortimer, who, suggests Dodd, would have known well that in the occasionally tumultuous parliaments of earlier reigns, "the trouble that had been caused in parliament had emanated almost exclusively from the barons".[71] The Archbishop of York, who had been summoned to the December parliament, was "conspicuous by his absence" from the January sitting.[72] Some Welsh MPs also received summonses, but these had deliberately been despatched too late for those elected to attend; others, such as the sheriff of Meirionnydd, Gruffudd Llwyd, refused to attend, out of loyalty to Edward II and also hatred of Roger Mortimer.[73]

Although a radical gathering, the parliament was to some degree consistent with previous assemblies, being dominated by lords reliant on a supportive Commons. It differed, though, in the greater-than-usual influence that outsiders and commoners had, such as those from London. The January–February parliament was geographically broader too, as it contained unelected members from Bury St Edmunds and St Albans: says Maddicott, "those who planned the deposition reached out in parliament to those who had no right to be there".[74][note 14] And, says Dodd, the rebels deliberately made parliament "centre stage" to their plans.[75]

Parliament assembled

The King's absence

Before parliament met, the lords had sent Adam Orleton (the Bishop of Hereford) and William Trussell to Kenilworth to see the King, with the intention of persuading Edward to return with them and attend parliament. They failed in this mission: Edward flatly refused and roundly cursed them. The envoys returned to Westminster on 12 January; by which time parliament had been sitting five days. It was felt that nothing could be done until the King had arrived:[76] historically a parliament could only pass statutes with the monarch present.[50][76][9][note 15] On hearing from Orleton and Trussell how Edward had denounced them, the King's opponents were no longer willing to let his absence stand in their way.[9] Edward II's refusal to attend failed to prevent the parliament from taking place, the first time this had ever happened.[78]

Constitutional crisis

The various titles bestowed on the younger Edward at the end of 1326—which acknowledged his unique position in government while avoiding calling him king—reflected an underlying constitutional crisis, of which contemporaries were keenly aware. The fundamental question was how the crown was transferred between two living kings, a situation which had never arisen before.[note 16] Valente has described how this "upset the accepted order of things, threatened the sacrosanctity of kingship, and lacked clear legality or established process".[79] Contemporaries were also uncertain as to whether Edward II had abdicated or was being deposed. On 26 October it had been recorded in the Close Rolls that Edward had "left or abandoned his kingdom",[9][note 17] and his absence enabled Isabella and Mortimer to rule.[82] They could legitimately argue that King Edward, having provided no regent during his absence (as would be usual), should make his son governor of the kingdom in his father's stead.[48] They also said Edward II held Parliament in contempt by calling it a treasonous assembly[82] and insulted those attending it as traitors".[52] It is unknown whether the King did, in fact, say or believe this, but it certainly suited Isabella and Mortimer for parliament to think so.[82] If Edward did denounce parliament then he probably did not realise how it could be used against him.[51] In any case, Edward's absence saved the couple the embarrassment of having a reigning king present when they deposed him, and Seymour Phillips suggests that if Edward had attended he may have found enough support to disrupt their plans.[52]

Proceedings of Monday, 12 January

Parliament had to consider its next step. Bishop Orleton—emphasising Isabella's fear of the King—asked the assembled lords whom they would prefer to rule, Edward or his son. The response was sluggish, with no rush to either depose or acclaim.[76] Deposition had been raised too suddenly for many members to stomach:[83] the King was still not entirely friendless,[64] and indeed, has been described by Paul Dryburgh as casting an "ominous shadow" over the proceedings.[84] Orleton suspended proceedings until the next day to allow the lords to dwell on the question overnight.[76] Also on the 12th, Sir Richard de Betoyne, the Mayor of London, and the Common Council wrote to the lords in support of both the Earl of Chester being made King and the deposition of Edward II, whom they accused of failing to uphold his coronation oath and the duties of the crown.[9] Mortimer, who was highly regarded by Londoners,[83][note 18] may well have instigated this as a means of influencing the lords.[9] The Londoners' petition also proposed that the new king should be governed by his Council until it was clear he understood his coronation oath and regal responsibilities. This petition the lords accepted; another, requesting the King should hold Westminster parliaments annually until he reached his majority, was not.[87]

Proceedings of Tuesday, 13 January

...the whole community of the realm there present, unanimously chose [Edward] to be guardian of the said kingdom ... and govern the said kingdom in the name and in the right of the Lord King his father, then being absent. And the same [Edward] there assumed the rule of the said kingdom on the same day in the form aforesaid, and began to exercise those things which were rightful under his privy seal, which was then in the custody of his clerk Sir Robert Wyville, because he did not then have any other seal for the said rule...[88]

Close Rolls, 26 October 1326

Whether Edward II resigned his throne or was forced from it[89] under pressure,[61] the crown legally changed hands on 13 January[89] with the support, it was recorded, of "all the baronage of the land".[13] Parliament met in the morning and then suspended itself.[89] A large group of the lords temporal and spiritual[note 19] made their way to the City of London's Guildhall where they swore an oath[89] "to uphold all that has been ordained or shall be ordained for the common profit".[92] This was intended to present those in parliament who disagreed with deposition with a fait accompli.[93] At the Guildhall they also swore to uphold the constitutional limitations of the Ordinances of 1311.[94][note 20]

The group then returned to Westminster in the afternoon, and the lords formally acknowledged that Edward II was no longer to be King.[89] Several orations were made.[96] Mortimer, speaking on behalf of the lords,[97] announced their decision. Edward II, he proclaimed, would abdicate and[96] "...Sir Edward ... should have the government of the realm and be crowned king".[98] The French chronicler Jean Le Bel described how the lords proceeded to document Edward II's "ill-advised deeds and actions" to create a legal record which was duly presented to parliament.[97] This record declared "such a man was unfit ever to wear the crown or call himself King".[99] This list of misdeeds—probably drawn up by Orleton and Stratford personally[98]—were known as the Articles of Accusation.[96][note 21] The bishops gave sermons—Orleton, for example, spoke of how "a foolish king shall ruin his people",[102] and, report Dunham and Wood, he "dwelt weightily upon the folly and unwisdom of the king, and upon his childish doings".[102] This, says Ian Mortimer, was "a tremendous sermon, rousing those present in the way he knew best, through the power of the word of God".[83] Orleton based his sermon on the biblical text "Where there is no governor the people shall fall"[103] from the Book of Proverbs,[note 22] while the Archbishop of Canterbury took for his text Vox Populi, Vox Dei.[106]

Articles of accusation

During the sermons, the articles of deposition were officially presented to the assembly. In contrast to the elaborate and floridly hyperbolic accusations previously launched at the Despensers, this was a relatively simple document.[106] The King was accused of being incapable of fair rule; of indulging false counsellors; preferring his own amusements to good government; neglecting England and losing Scotland; dilapidating the church and imprisoning the clergy; and, all in all, being in fundamental breach of the coronation oath he had made to his subjects.[47] All of which, the rebels claimed, was so well known as to be undeniable.[107] The articles accused Edward's favourites of tyranny although not the King himself,[107] whom they described as "incorrigible, without hope of reform".[108] England's succession of military failures in Scotland and France rankled with the lords: Edward had fought no successful campaigns in either theatre, yet had raised enormous levies to enable him to do so. Such levies says F. M. Powicke, "could only have been justified by military success".[109] Accusations of military failure were not wholly fair in placing the blame for these losses, as they did, so squarely on Edward II's shoulders: Scotland had arguably been almost lost in 1307.[107] Edward's father had, says Seymour Phillips, left him "an impossible task", having started the war without making sufficient gains to allow his son to finish it. And Ireland had been the theatre of one of the King's few military successes[107]—the English victory at the Battle of Faughart in 1318 had crushed Robert the Bruce's ambitions in Ireland (and seen the death of his brother).[110][note 23] Only the King's military failures, though, were remembered, and indeed, they were the most damning of all the articles:[112][note 24]

By the common consent of all, the archbishop of Canterbury declared how the good King Edward when he died had left to his son his lands of England, Ireland, Wales, Gascony and Scotland in good peace; how Gascony and Scotland had been as good as lost by evil counsel and evil ward [note 25] ...

The King's deposition

Every speaker on 13 January reiterated the articles of accusation, and all concluded by offering the young Edward as king, if the people approved him.[116] The crowd outside, which included a large company of unruly Londoners, says Valente,[117] had been "whipped ... into such fervour" by "dramatic outcries at appropriate points in the orations" from Thomas Wake,[117][note 26] who repeatedly rose and demanded of the assembly whether they agreed with each speaker; "Do you agree? Do the people of the country agree?"[93] Wake's exhortations—arms outstretched, says Prestwich, he cried "I say for myself that he shall reign no more")[34]—combined with the intimidating mob, led to tumultuous responses of "Let it be done! Let it be done!"[93] This, says May McKisack, gave the new regime a degree of "support of popular clamour".[36] The Londoners played a key role in ensuring that remaining supporters of Edward II were intimidated and overwhelmed by events.[9]

Edward III was proclaimed king.[118][119] At the end of the day, said Valente, "the electio of the magnates received the acclamatio of the populi, 'Fiat!,." Proceedings drew to a close with a chorus of Gloria, laus et honor,[117] and perhaps oaths of homage from the lords to the new king. Assent to the new regime was not universal: the Bishops of London, Rochester and Carlisle abstained from the day's affairs in protest,[117][note 27] and Rochester was later beaten up by a London mob because of his opposition.[83]

The King's response

The articles accused the king, the fount of justice, of a series of high crimes against his country. Instead of good government by good laws, he had ruled by evil counsel. Instead of justice, he had sent noblemen to shameful and illegal deaths. He had lost Scotland and Gascony, and he had oppressed and impoverished England. In short, he had broken his coronation oath—here treated as a solemn contract with his people and country—and he must pay the price.[121]

David Starkey, Crown and Country: A History of England Through the Monarchy

One final action remained to be taken: the ex-King in Kenilworth had to be informed that his subjects had chosen to withdraw their allegiance from him. A delegation was organised to take the news. The delegates were the Bishops of Ely, Hereford and London, and around 30 laymen.[9][74] Among the latter, the Earl of Surrey represented the lords and Trussell represented the shire knights.[9][note 28] The group was intended to be as representative of parliament—and so the kingdom—as possible.[124] It was not composed solely of parliamentarians, but there were enough of them in it to appear parliamentarian.[75] Its size also had the added advantage of spreading collective responsibility far more broadly than would have happened in a small group.[124][125] They left on or shortly after Thursday 15 January and had arrived in Kenilworth by either 21 or 22 January,[126] when William Trussell asked for the King to be brought to them in the name of parliament.[126]

Edward, dressed in a black gown and under the Earl of Lancaster's escort, was brought to the great hall.[80] Geoffrey le Baker's Chronicle describes how the delegates equivocated at first, "adulterating the word of truth" before coming to the point.[13] Edward was offered the choice of resigning in favour of his son, and being provided for according to his rank,[127] or of being deposed. This, it was emphasised, could lead to the throne being offered to someone, not of royal blood[126] but politically experienced,[80] clearly referring to Mortimer.[80][note 29] The King protested—mildly—and wept,[126] fainting at one point.[80] According to Orleton's later report, Edward claimed he had always followed the guidance of his nobles, but regretted any harm he had done.[103] The deposed king took comfort from his son succeeding him. It seems probable that a memorandum of acknowledgement was drawn up between the delegation and Edward, minuting what was said, although this has not survived.[126] Baker says that at the end of the meeting Edward's Steward, Thomas Blunt, dramatically broke his staff of office in half, and dismissed Edward's household.[note 30]

The delegation left Kenilworth for London on 22 January: their news preceded them.[130] By the time they reached Westminster, around 25 January, Edward III was already officially referred to as king, and his peace had been proclaimed at St Paul's Cathedral on the 24th. Now the new king could be proclaimed in public;[131] Edward III's reign was thus dated from 25 January 1327.[130] Behind the scenes, though, discussions must have begun on the thorny question of what to do with his predecessor,[132] who still had not had any judgement—legal or parliamentary—passed upon him.[133]

Subsequent events and aftermath

Recall of parliament

Original Latin: Henricus comes Lancastrie et Leicestrie queritur quod cum preceptum fuit cancellario quod deliberare faceret dicto comiti brevia de diem clausit extremum post mortem Thome nuper comitis Lancastrie fratris sui per que debeat inquiri de omnibus terris unde dictus Thomas obiit seisitus et de vero valore eorundem, etc., que brevia deliberata fuerunt per ipsum comitem escaetoribus et subescaetoribus, qui in extentis suis nullam fecerunt mencionem de feodis militum nec de advocacionibus ecclesiarum, unde petit remedium. Responsum. Habeat brevia de liberacione tam feodorum et advocacionum quam maneriorum, terrarum et tenementorum.

|

Edward III's political education was deliberately accelerated by the tutelage of advisors such as William of Pagula and Walter de Milemete.[135] Still a minor,[136] Edward III was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 1 February 1327:[137][note 31] executive power remained with Mortimer and Isabella.[139][note 32] Mortimer was made Earl of March in October 1328,[133] but otherwise, received few grants of land or money. Isabella, on the other hand, gained an annual income of 20,000 marks (£13,333)[note 33] within the month. She achieved this by requesting the return of her dower which her husband had confiscated; it was returned to her substantially augmented.[142] Ian Mortimer has called the grant she received as amounting to "one of the largest personal incomes anyone had ever received in English history".[138][143] Following Edward's coronation parliament was recalled.[126] According to precedent, a new parliament should have been summoned with the accession of a new monarch, and this failure of process indicates the novelty of the situation.[58] Official records regnally date the entire parliament to the first year of Edward III's reign rather than the last of his father's, even though it spread over both.[144]

When recalled, parliament returned to its usual business, and heard a large number (42) of petitions from the community.[9][note 34] These not only included the political—and often lengthy—petitions related directly to the deposition, but a similar number coming from the clergy and the City of London.[146] This was the greatest number of petitions to have been submitted by the Commons in the history of parliament.[62] Their requests ranged from confirmation of the acts against the Despensers[9][note 35] and those in favour of Thomas of Lancaster, to the reconfirmation of the Magna Carta. There were ecclesiastical petitions, and those from the shires dealt mainly in annulling debts and amercements of both individuals and towns. There were numerous requests for the King's grace, for example, overturning perceived false judgements in local courts and concerns for law and order in the localities generally.[9] Restoring law and order was a priority of the new regime,[37] as Edward II's reign had foundered on his inability to do so, and his failure then used to depose him.[148] The principle behind Edward's deposition was, supposedly, to redress such wrongs his reign had caused.[149] One petition requested members of the Commons be authorised to take written confirmation of their petition and its concomitant answer to their localities,[150] while another protested against corrupt local royal officials. This eventually resulted in a proclamation in 1330 instructing individuals who had cause of complaint or need of redress from such should attend the approaching parliament.[151]

The Commons too were concerned for the restoration of law and order, and one of their petitions called for the immediate appointment of wide-ranging keepers of the peace who could personally put men on trial. This request was agreed by the King's council.[152] This return to normal parliamentary business demonstrated, it was hoped, both the regime's legitimacy and its ability to repair the injustices of the previous reign.[9] Most of the petitions were accepted—resulting in seventeen statute articles—which indicates how keen Isabella and Mortimer were to placate the Commons.[147] When parliament finally dissolved on 9 March 1327, it had been the second longest, at seventy-one days, of the century to date;[62][note 36] further, notes Dodd, because of this it was "the only assembly in the late medieval period to outlive a king and see in his successor".[75]

The deposition of Edward II "exemplifies the feudal view of the tie of fealty, which really persisted for two centuries after the Conquest; namely, that if a lord persistently refuses justice to his man, the bond is broken and the man may, after openly "defying " his lord, make war upon him."[154]

Alfred O'Rahilly, 1922.

The dead Earl of Lancaster's titles and estates were restored to his brother Henry,[4] and the 1323 judgement against Mortimer, which exiled him, was overturned.[155] The invaders were also restored to their estates in Ireland.[84] In an attempt at settling the Irish situation, parliament issued ordinances on 23 February pardoning those who had supported Robert Bruce's invasion.[84] The deposed King was referred to only obliquely in official records—for example, as "Edward his father, when he was king,"[126] "Edward, the father of the King who now is"[156] or as he had been known as a youth, "Edward of Caernarfon".[128] Isabella and Mortimer were careful to try to prevent the deposition from tarnishing their reputations, reflected in their concern of not just obtaining Edward II's ex-post facto agreement to his removal, but then publicising his agreement.[157][note 37] The problem they faced was that this effectively involved having to rewrite a piece of history in which many people were actively involved and had taken place only two weeks earlier.[158]

The City of London also benefited. In 1321, Edward II had disenfranchised London, and royal officials, in the words of a contemporary, had "pris[ed] every privilege and penny out of the city", as well as deposing their mayor: Edward had ruled London himself through a system of wardens.[155] Gwyn Williams described this as "an emergency regime of dubious legality".[159] In 1327 Londoners petitioned the recalled parliament for their liberties to be restored, and, since they had been of valuable—probably crucial—importance in enabling the deposition,[160] on 7 March they received not just the rights Edward II had removed from them, but greater privileges than they had ever possessed.[160][note 38]

Later events

The overt manipulation of parliament was entirely Roger [Mortimer]'s doing ... Roger was able to say that the decision was with the assent of the people of parliament. The English monarchy had changed forever.[93]

Ian Mortimer, The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March

Meanwhile, Edward II was still imprisoned[161] at Kenilworth, and was intended to stay there forever.[102][note 39] Attempts to free him led to his transfer to the more secure Berkeley Castle in early April 1327.[161] Plotting continued, and he was frequently moved to other places.[164] Eventually being returned to Berkeley for good, Edward died there on the night of 21 September. Mark Ormrod described this as "suspiciously timely", for Mortimer, as Edward's almost-certain murder permanently removed a rival and a target for restoration.[165]

Parliamentary proceedings were traditionally drawn up contemporaneously and entered onto a parliament roll by clerks. The Roll of 1327 is notable, according to the History of as Parliament, because "despite the highly charged political situation in January 1327, [it] contains no mention of the process by which Edward II ceased to be king".[9] The roll only begins with the reassembling of parliament under Edward III in February, after the deposition of his father.[9] It is likely, says Phillips, that since those involved were aware of the precarious legal basis for Edward's deposition—and how it would not bear "too close an examination"[160]—there may never have been an enrolment: "Edward II had been airbrushed from the record".[160] Other possible reasons for the lack of an enrolment are that it would never have been entered on a roll because the parliament was clearly illegitimate, or because Edward III later felt it was undesirable to have an official record of a royal deposition in case it suggested a precedent had been set, and removed it himself.[144]

It was not long before the crisis affected Mortimer's relationship with Edward III. Notwithstanding Edward's coronation, Mortimer was the country's de facto ruler.[166] The high-handed nature of his rule was demonstrated, according to Ian Mortimer, on the day of Edward III's coronation. Not only did he arrange for his three eldest sons to be knighted, but—feeling a knight's ceremonial robes were inadequate—he had them dressed as earls for the occasion.[140] Mortimer himself occupied his energies in getting rich and alienating people, and the defeat of the English army by the Scots at the Battle of Stanhope Park (and the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton which followed it in 1328) worsened his position.[166] Maurice Keen describes Mortimer as being no more successful in the war against Scotland than his predecessor had been.[133] Mortimer did little to rectify this situation and continued to show Edward disrespect.[167] Edward, for his part, had originally (and unsurprisingly) sympathised with his mother against his father, but not necessarily for Mortimer.[19][note 40] Michael Prestwich has described the latter as a "classic example of a man whose power went to his head", and compares Mortimer's greed to that of the Despensers and his political sensitivity to that of Piers Gaveston.[143] Edward had married Philippa of Hainault in 1328, and they had a son in June 1330.[167][168] Edward decided to remove Mortimer from the government: accompanied and assisted by close companions, Edward launched a coup d'état which took Mortimer by surprise at Nottingham Castle on 19 October 1330. He was hanged at Tyburn a month later[169] and Edward III's personal reign began.[170]

Scholarship

... Although Edward II's reign as king ended in January 1327, his story did not end there. The lurid reports about the brutal, and possibly symbolic, manner of Edward II's death the following September have fuelled a prurient interest in him on the one hand, while on the other the circulation of claims that he had instead survived and escaped from captivity gave him in effect a long 'after-life' which has provided endless scope for further research and speculation.[171]

Seymour Phillips, The Reign of Edward II: New Perspectives

The parliament of 1327 is the focus of two main areas of interest for historians: in the long term, the part it played in the development of the English parliament, and in the short term, its place in the deposition of Edward II. On the first point, Gwilym Dodd has described the parliament as a landmark event in the institution's history,[172] and, say Richardson and Sayles, it began a fifty-year period of developing and honing procedure.[173] The assembly also, suggests G. L. Harriss, marks a point in the history of the English monarchy in which its authority was curtailed to a similar degree to the limitation previously imposed on King John by the Magna Carta and Henry III by de Montfort.[174] Maddicott agrees with Richardson and Sayles regarding the significance of 1327 for the development of separate chambers, because it "saw the presentation of the first full set of commons' petitions [and] the first comprehensive statute to derive from such petitions".[175] Maude Clarke described its significance as being in how "feudal defiance" was for the first time subsumed to the "will of the commonality, and the King was rejected not by his vassals but by his subjects".[176]

The second question it raises for scholars is whether Edward II was deposed by parliament, as an institution, or just while parliament sat.[61] While many of the events necessary for the King's removal had taken place in parliament, others of equal significance (for example, the oath-taking at the Guildhall) occurred elsewhere. Parliament was certainly the public setting for the deposition.[61] Victorian constitutional historians saw Edward's deposition as demonstrating fledgeling authority by the House of Commons akin to their own parliamentary system.[80] Twentieth-century historiography remains divided on the issue. Barry Wilkinson, for example, considered it a deposition—but by the magnates, rather than parliament—but G. L. Harriss termed it an abdication,[79] believing "there was no legal process of deposition, and kings like ... Edward II were induced to resign".[177] Edward II's position has been summed up as his being offered "the choice of abdication in favour of his son Edward or forcible deposition in favour of a new king selected by his nobles".[178] Seymour Phillips has argued that it was the "combined determination of the leading magnates, their personal followers and the Londoners" that Edward should be gone.[61]

To try to determine precisely how it was that Edward II was removed from the throne, whether by abdication, deposition, Roman legal theory, renunciation of homage, or parliamentary decision is a futile task. What was necessary was to ensure that every conceivable means of removing the King was adopted, and the procedures combined all possible precedents.[179]

Michael Prestwich

Chris Bryant argues it is not clear whether these events were driven by parliament, or merely happened to occur in parliament, although he suggests Isabella and Roger Mortimer thought it necessary to have parliamentary support.[118] Valente has suggested "the deposition was not revolutionary and did not attack kingship itself",[132] it was not "necessarily illegal and outside the bounds of the 'constitution'",[132] even though historians commonly describe it as such. The discussion is confused further, she says, because varying descriptions are given of the assembly by contemporaries. Some described it as being a royal council, others called it a parliament in the King's absence or a parliament with the Queen presiding,[132] or one summoned by her and Prince Edward.[180] Ultimately, she wrote, it was magnates deciding on policy, and being able to do so through the support of the knights and commoners.[181]

Dunham and Wood suggested that Edward's deposition was forced by political rather than legal factors.[102] There is also a choice of who deposed: whether "the magnates alone deposed, that the magnates and people jointly deposed, that Parliament itself deposed, even that it was the 'people' whose voice was decisive".[82] Ian Mortimer has described how "the representatives of the community of the realm would be called upon to act as an authority over and above that of the King".[50] It was no advance of democracy, and was not intended to be—its purpose was to "unite all classes of the realm against the monarch" of the time.[50] John Maddicott has said the proceedings began as a baronial coup but ended up becoming something close to a "national plebiscite",[64] in which the commons were part of a radical reform of the state.[182] This parliament also clarified procedures, such as codifying petitioning, legislating for it, and promulgating statutes, which would become the norm.[147]

Magnates and prelates had deposed a King in response to the clamour of the whole people. That clamour had a distinct London accent.[183]

Gwyn A. Williams

The parliament also illustrates how contemporaries viewed the nature of tyranny. The leaders of the revolution, aware that deposition was a barely understood and unpopular concept in the political culture of the day, began almost immediately re-casting events as an abdication instead.[184] Few contemporaries overtly disagreed with Edward's deposition, "but the fact of deposition itself caused immense anxiety", suggested David Matthews.[185] It was an event as yet unheard of in English history.[34][note 41] Phillips comments that "using accusations of tyranny to remove a legitimate and anointed king were too contentious and divisive to be of any practical use",[135] which is why Edward had been accused of incompetence and inadequacy and much else, and not of tyranny.[135][note 42] The Brut Chronicle, in fact, goes so far as to ascribe Edward's deposition, not to intentions of men and women, but to the fulfilment of a prophecy by Merlin.[130]

Edward's deposition also set a precedent and laid out arguments for subsequent depositions.[47] The 1327 articles of accusation, for example, were drawn on sixty years later during the series of crises between King Richard II and the Lords Appellant. When Richard refused to attend parliament in 1386, Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester and William Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury visited him at Eltham Palace[189] and reminded him how—per "the statute by which Edward [II] had been adjudged"[190]—a King who did not attend parliament was liable to deposition by his lords.[191]

Indeed, it has been suggested Richard II may have been responsible for the disappearance of the 1327 parliament roll when he recovered personal power two years later.[192][note 43] Given-Wilson says that Richard considered Edward's deposition a "stain which he was determined to remove"[194] from the royal family's history by proposing Edward's canonisation.[194] Richard's subsequent deposition by Henry Bolingbroke in 1399 naturally drew direct parallels with that of Edward. Events which had taken place over 70 years earlier were by 1399 considered "ancient custom",[196] which had set legal precedent, if an ill-defined one.[196] A prominent chronicle of Henry's usurpation, composed by Adam of Usk, has been described as bearing "a striking resemblance" to the events of the 1327 parliament. Indeed, said Gaillard Lapsley, "Adam uses words that strongly suggest that he had this precedent in mind."[197]

Edward II's deposition was used as political propaganda as late as the troubled last years of James I in the 1620s. The King was very ill and played a peripheral role in government; his favourite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham became proportionately more powerful. Attorney general Henry Yelverton publicly compared Buckingham to Hugh Despenser on account of Villiers' penchant for enriching his friends and relatives through royal patronage.[198] Curtis Perry has suggested that 17th-century "contemporaries applied the story [of Edward's deposition] to the political turmoil of the 1620s in conflicting ways: some used the parallel to point towards the corrupting influence of favourites and to criticize Buckingham; others drew parallels between the verbal intemperance of Yelverton and his ilk and the unruliness of Edward's opponents".[199]

The Parliament of 1327 was the last parliament before the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 to summon Welsh representatives. They never took their seats,[118] having been deliberately summoned too late to attend, because South Wales supported Edward, and North Wales was equally opposed to Mortimer.[50] The 1327 parliament also provided almost the same list of attendees for the next five years of parliaments.[63]

Cultural depictions

Christopher Marlowe was the first to dramatise the life and death of Edward II, with his 1592 play Edward II (or The Troublesome Reign and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second, King of England, with the Tragical Fall of Proud Mortimer). Marlowe emphasises the importance of parliament in Edward's reign, from his original taking of the coronation oath (Act I, scene 1), to his deposition (in Act V, scene 1).[200]

Notes

- This had not always been the case. For most of her marriage, she had been a loyal wife who had provided the King with four children. Moreover, she was politically active in Edward's cause, having shared his hatred of the Earl of Lancaster, and played a pivotal role in Anglo-French relations.[7] This is at variance with the impression received from chroniclers writing under Isabella and Mortimer between 1327 and 1330, who, says Lisa St John, tend to give "the impression that Isabella's relationship with Edward was dysfunctional from the start".[8]

- Edward II's attitude was summed up by a contemporary, who reported that the King "carried a knife in his hose to kill queen Isabella, and had said that if he had no other weapon he would crush her with his teeth".[9]

- Indeed, the King threatened to "ordain in such wise that Edward shall feel it all the days of his life and that all other sons shall take example thereby of disobeying their lords and father".[16] Historian Mark Ormrod suggests that the young Edward had never, until then, "experienced so powerfully and so long the full force of Isabella's dominant personality and her strident assertion of maternal authority".[17] King Edward's behaviour combined an increasingly threatening attitude with a complete dearth of familial affection, and this meant that when the king tried to appeal to his son's sense of loyalty, it came to nothing.[18]

- Hugh Despenser had a spy within the household of Roger Mortimer in Calais, who not only informed him of Mortimer's eventual landing place but also alerted Despenser to Mortimer's various diversionary tactics in the meantime.[27]

- Orleton was one of the leading political thinkers of his day, and he has been described by Kathleen Edwards as being a "combination of ability, subtlety, and boldness in seizing opportunities"; although a firm supporter of the Queen, over the three years following Edward II's deposition, "Orleton was quite unscrupulous in putting his own interests before those of Mortimer".[30]

- Either to the West Country, where the bulk of Mortimer's estates lay,[9] or to raise the Welsh Marches against Mortimer in a rebellion similar to that which had forced him into exile in 1322. The Welsh had provided the bulk of the King's army then, so, once again being in need of support and soldiers, it was logical for Edward to seek their support once again.[31]

- The London mobs pursued those senior officials most closely associated with Edward II, and who had been left exposed by the King's flight from London.[37] Targets included Walter Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter, who was Treasurer, and the Chancellor, Robert Baldock, whom they also imprisoned[38] in Newgate prison before his murder.[39] There was an "orgy of rioting, murder and looting", wrote Natalie Fryde:[40] Londoners were influenced by a letter from Isabella—described by May McKisack as inflammatory[41]—that had recently been received by the mayor, Hamo de Chigwell, pleasing their help. A volatile public meeting robustly informed the mayor of the mob's command: that "Stapledon was the Queen's enemy and that all those hostile to Isabella and her cause should be put to death".[42] The contemporary Annales Paulini chronicle describes how the mob "attacked and robbed the London property of the King's Treasurer, Bishop Stapledon[43] (who had published bulls of excommunication against Edward II's political opponents),[36] forcing him to flee to St Paul's, where he was hit on the head and then dragged into Cheapside to be beheaded ... Stapledon's head was then sent to the Queen who was residing in Bristol".[43] That same October, another mob had broken into the Tower of London and forced the Constable of the Tower, John de Weston, to release all the prisoners he held. The mobs proclaimed their loyalty to Queen Isabella at the Guildhall; some other senior government officials within government only escaped Stapledon's fate by fleeing for their lives.[44]

- With Isabella and Mortimer, says Ormrod, were the Archbishop of Dublin (his counterpart of Canterbury, says Ormrod, was "keeping out of sight and dithering"[46] over his loyalties), the Bishops of Winchester, Ely, Lincoln, Hereford and Norwich, the earls of Norfolk, Kent and Leicester, Thomas Wake, Henry Beaumont, William de la Zouche, amongst others.[45]

- The writs were not just issued in the name of the King, but were sealed in Chancery as if they had been instructed from Kenilworth, where the King was confined. This was a bureaucratic fiction; Mortimer and the Queen instructed Chancery, first from Woodstock, then from Wallingford, and Ormrod is clear that "no one actively involved in the regime was now under any illusion as to where the source of royal authority lay".[53]

- And one that did not go unnoticed by contemporary observers: Ormrod cites the case of the Bishop of Salisbury's registrar, who "took great exception" to the misuse of the King's seal in authenticating his bishop's writ of parliamentary summons.[54]

- Ian Mortimer goes on to note that "the hardest line was taken by the Lancastrians, whose world had been shattered by Edward's destruction of Thomas of Lancaster. Roger had been saved from his death sentence in 1322 by the King's intervention, and indeed had for many years before that been a loyal supporter of the King. Even now as a royalist, he wanted to gain Prince Edward's respect, which was very unlikely to be forthcoming if he were held responsible for the death of his father."[59]

- This, says Maddicott, compared favourably to contemporary salaries. These amounts remained the fixed rate for parliamentary attendance for the next fifty years.[65]

- Historians H. G. Richardson and G. O. Sayles have identified the 1327 parliament as the point when knights of the shires and burgesses started to be consistently summoned to parliament.[69] What had previously been an indulgence of the king had become the "right—perhaps we should say the duty" of the Commons to attend.[70] Although, they say, "the intention behind this was doubtless political", it was still an important shift in the balance of power between the two classes of MPs. Until now, for example, the difference between knight and baron was still relatively fluid, and indeed, in the 1306 parliament, they sat together.[69]

- In this, John Maddicott has compared the 1327 parliament with that of 1311 (which published the Ordinances against Edward II and exiled Piers Gaveston, and the 1321 assembly, which had exiled the Despensers.[74]

- On the other hand, Edward II had regularly missed periods of his own parliaments, for reasons ranging from absence in other parts of the realm (the parliament of August–October 1311) to diplomatic missions abroad (July 1313), or "important" but otherwise undescribed business (in September 1314). Some parliaments he completely missed, sometimes for stated reasons (such as that of March–April 1313, which Edward missed due to illness), but often with no reason being recorded, such as the parliament of November–December 1311.[77]

- This was the first time a king had been deposed since the Norman Conquest; even the barons who rebelled against King John in 1215 (to the extent of welcoming a French invasion against him) had never formally attempted to depose him. And the barons aligned to Simon de Montfort who revolted against his son, Henry III, seem to have never even mentioned it.[79] It was not only the first deposition in English history, but no European ruler of equivalent status had suffered the fate (with the exception, says Ian Mortimer, of a "minor German prince of small reputation earlier in the fourteenth century".[80]

- Even if, as J. R. S. Phillips has noted, when Edward had been captured he had been attempting to escape to Ireland: If he had reached there successfully, the accusation of abandoning his realm would have fallen since, at that time, Ireland was part of the royal dominions.[81]

- The new mayor (also spelt de Bethune) had been one of Mortimer's most loyal supporters for some years by the time of his mayoralty.[50] Edward II had commuted his death sentence in 1323 and had him committed to the Tower; in August, Mortimer had contrived to escape to France, and it seems probable that de Bethune[85] and John de Gisors (a former mayor)[86] had been Mortimer's accomplices. May McKisack has suggested—following Froissart's chronicle—that it was London's civic leaders who had originally invited Isabella and Mortimer to invade England, telling them that they would find London and most other towns ready to support them.[41]

- The group was composed of twenty-four barons, two archbishops, twelve bishops, seven abbots and priors twelve elected shire knight (and one who was unelected), thirty men from the Cinque Ports, thirteen from St Albans, and five from Bury St Edmunds. This group included men who were not formally attending the parliament but were closely aligned with the protagonists (for example, Isabella's household knights took the oath), as well as omitting some who would have been expected to attend but whom the political situation kept out of London (the Earl of Lancaster, for instance, was guarding Edward II at Kenilworth Castle).[90][91]

- The 1311 ordinances specifically restricted the King's reliance on any perceived as "evil councillors" (such as Gaveston) and placed other limits on royal power, which was replaced by baronial control. The King could only appoint officials "by the counsel and assent of the baronage, and that in parliament". Likewise, the baronial council had the deciding say on the launching of foreign wars, and parliament had to be held annually.[95]

- It was described by Adam Orleton as a concordia; the term "articles of accusation" was first used by nineteenth-century historians George Burton Adams and H. Morse Stephens in their Select Documents of English Constitutional History,[100] where they printed the document in full.[101]

- Specifically, Proverbs 11:14, a well-known verse that could be loaded, when necessary, with political weight. "And it is impossible that one governs others usefully when he is subverted by his own errors", said John of Salisbury of this verse, in the context of "what bad and good happens to subjects on account of the morals of their rulers". John of Salisbury wrote in the twelfth-century;[104] in the fourteenth, William of Occam also described the dangers to souls if a "ruler would not have sufficient authority to control things subjected to him, and in such a case the saying of Solomon [at Proverbs 11:14] would apply".[105]

- As Mark Ormrod puts it, "Whatever his other deficiencies, Edward of Caernarfon tended to be resolute in the defence of his theoretical rights".[111]

- In fact, Powicke says, many attendees of the 1327 parliament would have had direct knowledge of the catastrophic 1322 campaign, particularly among the knights of the shire (less so for the barons, only a few of whom had taken part): "The class of county knights, organised in their thirty-seven county communities, supplied nearly all the judicial and administrative leadership in the nation",[113] as a result of which the ordinary soldier would identify more with them in the localities than with an earl or baron.[113]

- "Ward" in this context probably refers to "A judicial decision, verdict, or award or a similar authoritative judgment"[114] or possibly a reference to the King's guardians having failed him.[115]

- Seymour Phillips has suggested that Wake—who was the absent Earl of Lancaster's son-in-law—was standing in for Lancaster during the parliamentary proceedings and acting at the earl's command and in his interests.[66]

- It is possible, says Valente, that the proceedings saw oaths of homage and fealty being given to one king before they had been formally withdrawn from another.[120]

- According to the contemporary Lanercost Chronicle, which provides the most detailed report as to the precise composition of the delegation to Edward, it had twenty-four members. The Chronicle lists them as being "two bishops (Winchester and Hereford) two earls (Lancaster and Surrey), two barons (William of Ross and Hugh de Courtenay), two abbots, two priors, two justices, two Dominicans, two Carmelites, four knights (two from North of the Trent and two from South of the Trent), two citizens of London, and two citizens of the Cinque Ports".[9] The chronicler also claims that the Queen explicitly forbade Franciscans—which she favoured above all other religious orders in England—from joining, to spare them the subsequent unpleasant duty of having to bring her bad news.[122] It is also the case, though, that the Lanercost chronicler omits any mention of either Trussell (who is known to have been there) or the Bishops of Ely or London.[9] Trussell, incidentally, had been a judge at the trial of Hugh Despenser the Younger in Hereford the previous November.[123]

- Although, as Phillips points out, the delegation's threat to disinherit Edward II and break the line of succession was clearly "an empty one, since the placing on the throne of anyone other than the young Edward would scarcely have met with general acceptance and would have been a recipe for civil war".[128] Further, for this ever to have been possible, it would have been necessary for both Edward II's half-brothers, Thomas, Earl of Norfolk and Edmund, Earl of Kent, as well as his sons Edward and John to have been dead, and Phillips considers that "there is no reason to believe that such a move was ever considered".[129]

- Dunham and Wood note that the act of breaking a virge, or staff, in this context, was deeply symbolic, as it was traditionally done over the grave of a dead king.[102]

- The Bishop of Rochester, says Ian Mortimer, attended the coronation, if "still nursing his bruises".[138]

- Not only did the couple control who had access to the new King, they advised him, appointed government officials in his name, and even kept the privy seal in their own possession.[140]

- The mark was a medieval accounting unit, and was valued at two-thirds of a pound (13s. 4d. or 160d.)[141]

- Petitioning was the mechanism by which medieval litigants appealed for justice from the King personally, if they felt they had not received it through his courts, or if they desired the King's grace or bounty. The litigant could be an individual, a group, a community or even a town. A petition would be presented by the petitioner in parliament personally to the parliamentary receivers of petitions, who would pass it to the triers of petitions (those who evaluated them). If it was a simple matter, it would probably be dealt with by parliament immediately; the more complex cases would be passed to the King's council for discussion with the King before resolution.[145]

- The duration of Mortimer's and Isabella's regime was to see 140 such acts against the Despensers.[147]

- "Prior to 1327", wrote Richardson and Sayles, "business other than judicial can have taken very little time".[153]

- The importance that Isabella and Mortimer placed on receiving Edward II's agreement to his own removal is indicated, says Valente, by the fact that in the (admittedly short) period between Edward III's coronation and his father's acquiescence, there were almost no official actions undertaken by government, and no Letters Patent or Close were issued in the new King's name.[157]

- This included the automatic appointment of the mayor as a royal justice of Newgate and escheator, and also the new charter guaranteed that the city's liberties could no longer be forfeit as the result of the actions of a single city official. The new King, says Caroline Barron, "decided to work through the London mayors rather than against them".[155]

- Although he does not seem to have been particularly ill-treated: his son sent him two tuns of Rhenish wine, and supplies of "wine, wax, spices, eggs, cheese, capons, cattle" are evidenced in the Berkeley Castle muniments. His bed, clothes, and other various personal effects had been sent to his wife on his capture.[162] The choice of the west country as the location of his imprisonment was, says Natalie Fryde, determined by the weaknesses of the new regime: the north was ruled out because the regional English barons were notoriously unreliable and proximity to Scotland risked an invasion from Scottish lords sympathetic to Edward, such as the Earl of Mar. In the south, on the other hand, the recent volatility of London and Londoners' willingness to rebel probably made the Tower of London seem risky.[163]

- In fact, says Ormrod, Edward III rightly or wrongly seems to have held Mortimer—rather than the Despensers—as the true cause of the rift between Isabella and Edward II in 1326.[19]

- Prestwich notes that "there was no workable English precedent; chronicle tales taken from Geoffrey of Monmouth's fantasy Arthurian history may have told of kings being removed from office, but did not give any details of how to do it".[34]

- Contemporary analyses of royal tyranny are ambiguous. Both John of Salisbury ("a tyrant ... brings the laws to nought")[186] and Bracton ("the King who violates his duty to maintain justice ... is no longer a king, but a tyrant")[187] are clear about what constituted tyranny in the medieval mind. Both are also equivocal about what action to take against a tyrant, and Bracton, at least, refuses to justify tyrannicide.[188]

- The earldom of Lancaster provides another direct link between the two Kings; in 1397, there was rumoured to be major plotting against John of Gaunt, to which Richard II was said to be a party. The King, allegedly, was intending to repeal the act of the 1327 parliament which restored Henry of Lancaster, which would, in turn, have reaffirmed the 1322 confiscation:[193] "From such a process there could be but one real loser: the house of Lancaster".[194] Gaunt held his Lancastrian titles and estates through his wife, Blanche (Earl Henry, restored 1328, was her grandfather).[195]

References

- Le Baker 2012, p. 11.

- Powicke 1956, p. 114.

- Prestwich 2003, p. 70.

- Given-Wilson 1994, p. 553.

- Given-Wilson 1994, p. 571.

- Warner 2014, p. 196.

- Doherty 2003, p. 90.

- St John 2014, p. 24.

- Given-Wilson et al. 2005.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 32.

- Parsons 2004.

- Lord 2002, p. 45 n.5.

- Dunham & Wood 1976, p. 739.

- Peters 1970, p. 217.

- Ormrod 2006, p. 41.

- Fryde 1979, p. 185.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 34.

- Ormrod 2011, pp. 36–37.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 36.

- Waugh 2004.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 215.

- McKisack 1959, p. 93.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 35.

- Phillips 2011, p. 531 n.38.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 37.

- Doherty 2003, pp. 105–132.

- Cushway 2011, p. 13.

- Cushway 2011, p. 14.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 41.

- Edwards 1944, pp. 343, 343 n.5.

- Chapman 2015, p. 219.

- Phillips 2011, p. 512.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 42.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 216.

- Home 1994, p. 126.

- McKisack 1979, p. 82.

- Verduyn 1993, p. 842.

- Kaeuper 2000, p. 86.

- Mortimer 2010, p. 162.

- Fryde 1979, p. 193.

- McKisack 1979, p. 81.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 43.

- Liddy 2004, pp. 47–48.

- Dryburgh 2016, p. 30.

- Ormrod 2011, pp. 512–513.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 512.

- Dunham & Wood 1976, p. 740.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 44.

- Valente 2016, p. 231.

- Mortimer 2010, p. 166.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 513.

- Phillips 2011, p. 525.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 48.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 49.

- Wood 1972, p. 533.

- Phillips 2011, p. 537.

- Fryde 1996, p. 526.

- Bradford 2011, p. 192 n.15.

- Mortimer 2010, p. 165.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 47.

- Phillips 2011, p. 538.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 359.

- Powell & Wallis 1968, pp. 310–314.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 360.

- Maddicott 1999, p. 78.

- Phillips 2011, p. 532 n.63.

- Clarke 1933, p. 42.

- Roskell 1965, p. 5.

- Richardson & Sayles 1930, pp. 44–45.

- Richardson 1946, p. 27.

- Dodd 2006, p. 170.

- Phillips 2011, p. 532 n.86.

- Chapman 2015, p. 54.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 361.

- Dodd 2006, p. 168.

- Valente 1998, p. 855.

- Bradford 2011, pp. 191–192.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 217.

- Valente 1998, p. 852.

- Mortimer 2010, p. 169.

- Phillips 2006, p. 232.

- Valente 1998, p. 869.

- Mortimer 2010, p. 167.

- Dryburgh 2006, p. 136.

- Hilton 2008, pp. 259–292.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 479.

- Hartrich 2012, p. 97.

- H. M. S. O. 1892, pp. 655–656.

- Valente 1998, p. 858.

- Phillips 2011, p. 432 n.59.

- Phillips 2011, p. 432 n.63.

- Keen 1973, p. 76.

- Mortimer 2010, p. 168.

- Bryant 2015, p. 66.

- Prestwich 2005, pp. 182–183.

- Valente 1998, p. 856.

- Phillips 2011, p. 527.

- Valente 1998, p. 857.

- Le Bel 2011, pp. 32–33.

- Valente 1998, p. 856 n.6.

- Adams & Stephens 1901, p. 99.

- Dunham & Wood 1976, p. 741.

- Phillips 2011, p. 528.

- Forhan & Nederman 1993, p. 39.

- Lewis 1954, p. 227.

- Phillips 2011, p. 529.

- Phillips 2011, p. 530.

- Ormrod 2006, p. 32.

- Powicke 1960, p. 556.

- McNamee 1997, pp. 166–205.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 31.

- Powicke 1960, pp. 556–557.

- Powicke 1960, p. 557.

- M. E. D. 2014a.

- M. E. D. 2014b.

- Valente 1998, pp. 858–859.

- Valente 1998, p. 859.

- Bryant 2015, p. 67.

- Camden Society 1935, p. 99.

- Valente 1998, p. 859 n.6.

- Starkey 2010, p. 225.

- Gransden 1996, p. 14.

- Holmes 1955, p. 262.

- Phillips 2011, p. 534.

- Phillips 2011, p. 534 n.76.

- Valente 1998, p. 860.

- McKisack 1959, p. 90.

- Phillips 2011, p. 535.

- Phillips 2011, p. 535 n.81.

- Phillips 2011, p. 536.

- Valente 1998, p. 861.

- Valente 1998, p. 862.

- Keen 1973, p. 77.

- National Archives 1326.

- Phillips 2011, p. 531.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 220.

- Mortimer 2006, p. 54.

- Mortimer 2010, p. 171.

- Holmes 1957, p. 9.

- Mortimer 2010, p. 170.

- Spufford 1988, p. 223.

- Liddy 2004, p. 55.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 221.

- Phillips 2011, p. 539 n.105.

- Keeney 1942, p. 334.

- Harriss 1999, p. 50.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 364.

- Verduyn 1993, p. 843.

- Keeney 1942, p. 333.

- Maddicott 1999, p. 81.

- Harriss 1999, p. 45.

- Verduyn 1993, p. 845.

- Richardson & Sayles 1930, p. 45.

- O'Rahilly 1922, p. 173.

- Barron 2005, p. 33.

- Ormrod 1990, p. 6.

- Valente 1998, p. 870.

- Valente 1998, p. 876.

- Williams 2007, p. 287.

- Phillips 2011, p. 539.

- Phillips 2011, pp. 542–543.

- Phillips 2011, p. 541.

- Fryde 1979, p. 201.

- Phillips 2011, p. 547.

- Ormrod 2011, p. 177.

- McKisack 1959, pp. 98–100.

- Mortimer 2006, p. 67.

- Mortimer 2006, p. 81.

- Keen 1973, p. 105.

- Prestwich 2005, pp. 223–224.

- Phillips 2006, p. 2.

- Dodd 2006, p. 165.

- Richardson & Sayles 1931.

- Harriss 1976, p. 35.

- Maddicott 1999, p. 86.

- Clarke 1933, p. 43.

- Harriss 1994, p. 14.

- Amt & Smith 2018, pp. 305–306.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 218.

- Valente 1998, p. 863 n.3.

- Valente 1998, p. 168.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 363.

- Williams 2007, p. 298.

- Valente 1998, p. 853.

- Matthews 2010, p. 81.

- Rouse & Rouse 1967, pp. 693–695.

- Schulz 1945, pp. 151–153.

- Phillips 2011, p. 531 n.53.

- Saul 1997, pp. 171–175.

- Goodman 1971, pp. 13–15.

- Brown 1981, p. 113.n.

- Clarke 1964, p. 177 n.1.

- Given-Wilson 1994, p. 560.

- Given-Wilson 1994, p. 567.

- Palmer 2007, p. 116.

- Giancarlo 2002, p. 98.

- Lapsley 1934, p. 437 n.4.

- Stewart 2004, p. 314.

- Perry 2003, p. 313.

- Knowles 2001, p. 108.

Sources

- Adams, G.; Stephens, H. M., eds. (1901). Select Documents of English Constitutional History. New York: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 958650690.

- Amt, E.; Smith, K. A., eds. (2018). Medieval England, 500–1500: A Reader, Second Edition. Readings in Medieval Civilizations Cultures VI (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-44263-465-7.

- Barron, C. M. (2005). London in the Later Middle Ages: Government and People 1200–1500. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19928-441-2.

- Bradford, P. (2011). "A Silent Presence: The English King in Parliament in the Fourteenth Century". Historical Research. 84: 189–211. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2009.00532.x. OCLC 300188139.

- Brown, A. L. (1981). "Parliament, c. 1377–1422". In Davies, R. G.; Denton, J. H. (eds.). The English parliament in the Middle Ages. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 109–140. ISBN 978-0-71900-833-7.

- Bryant, Chris (2015). Parliament: The Biography. Vol. I. London: Transworld. ISBN 978-0-55277-995-1.

- Camden Society (1935). Parliament at Westminster, Epiphany-Candlemas 1327. third. Vol. 51. London: Camden Society. OCLC 4669199754.

- Chapman, A. (2015). Welsh Soldiers in the Later Middle Ages, 1282–1422. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-78327-031-6.

- Clarke, M. V. (1933). "Committees of Estates and the Deposition of Edward III". In Edwards, J. G.; Galbraith, V. H.; Jacob, E. F. (eds.). Historical Essays in Honour of James Tait. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 27–46. OCLC 499986492.

- Clarke, M. V. (1964) [First published 1936]. Medieval Representation and Consent: A Study of Early Parliaments in England and Ireland (repr. ed.). New York: Russell & Russell. OCLC 648667330.

- Cushway, G. (2011). Edward III and the War at Sea: The English Navy, 1327–1377. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-621-6.

- Dodd, D. (2006). "Parliament and Political Legitimacy in the Reign of Edward II". In Musson, A.; Dodd, G. (eds.). The Reign of Edward II: New Perspectives. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 165–189. ISBN 978-1-90315-319-2.

- Doherty, P. (2003). "The She-Wolf Triumphant". Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II. London: Carroll & Graf. pp. 105–132. ISBN 978-0786711932.

- Dryburgh, J. (2006). "The Last Refuge of a Scoundrel? Edward II and Ireland, 1321–7". In Musson, A.; Dodd, G. (eds.). The Reign of Edward II: New Perspectives. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 119–140. ISBN 978-1-90315-319-2.

- Dryburgh, P. (2016). "John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall (1316–36)". In Bothwell, J.; Dodd, G. (eds.). Fourteenth Century England. Vol. IX. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 23–48. ISBN 978-1-78327-122-1.

- Dunham, W. H.; Wood, C. T. (1976). "The Right to Rule in England: Depositions and the Kingdom's Authority, 1327–1485". The American Historical Review. 81: 738–761. doi:10.2307/1864778. OCLC 1830326.

- Edwards, K. (1944). "The Political Importance of the English Bishops during the Reign of Edward II". The English Historical Review. 59: 311–347. doi:10.1093/ehr/lix.ccxxxv.311. OCLC 2207424.

- Forhan, K. L.; Nederman, C. J. (1993). Medieval Political Theory: A Reader: The Quest for the Body Politic 1100–1400. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41506-489-7.

- Fryde, E. B. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52156-350-5.

- Fryde, N. (1979). The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II 1321–1326. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52154-806-9.