Tunceli Province

Tunceli Province (Turkish: Tunceli ili), formerly Dersim Province (Kurdish: Parêzgeha Dêrsim; Zazaki: Dêsim wilayet; Armenian: Դերսիմի մարզ), is a province in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey.[3] The province is considered part of Turkish Kurdistan and has a Kurdish majority. Moreover, it is the only province in Turkey with an Alevi majority.[4][5] Its population is 84,366 (2022).[1] The province has eight municipalities, 366 villages and 1,087 hamlets.[3]

Tunceli Province | |

|---|---|

Munzur River runs through the province | |

Location within Turkey | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Established | 25 December 1935 |

| Seat | Tunceli |

| Government | |

| • Vali | Bülent Tekbıyıkoğlu |

| Area | 7,582 km2 (2,927 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[1] | 84,366 |

| • Density | 11/km2 (29/sq mi) |

| Time zone | TRT (UTC+3) |

| Area code | 0428[2] |

| Website | www |

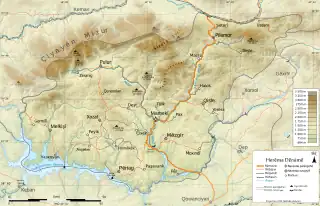

Geography

The adjacent provinces are Erzincan to the north and west, Elazığ to the south, and Bingöl to the east. The province covers an area of 7,582 km2 (2,927 sq mi).[6] Tunceli is traversed by the northeasterly line of equal latitude and longitude. The Munzur Valley National Park is also situated in the province.[7]

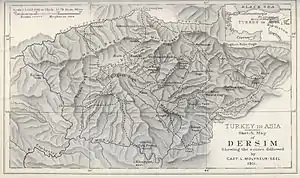

Tunceli Province is a plateau characterized by its high, thickly forested mountain ranges. The historical region of Dersim, which largely corresponds to Tunceli Province, lies roughly between the Karasu and Murat rivers, both tributaries of the Euphrates.[8]

Name

Tunceli, which is a modern name, literally means "bronze fist" in Turkish (tunç meaning "bronze" and eli (in this context) meaning "fist"). It shares the name with the military operation that the Dersim Massacre was conducted under.[9]

It has been proposed that the name Dersim is connected with various placenames mentioned by ancient and classical writers, such as Daranis, Derxene (a district of Armenia mentioned by Pliny), and Daranalis/Daranaghi (a district of Armenia mentioned by Ptolemy, Agathangelos, and Faustus of Byzantium).[10][11] One theory as to the origin of the name associates it with Darius the Great.[10]

One Armenian folk tradition derives the name Dersim from a certain 17th-century priest named Der Simon, who, fearing the maurading Celali rebels, proposed that his parishioners convert to the Alevi faith of their Kurdish neighbors. The proposal was accepted, and the Armenian converts renamed their home region Dersimon in honor of their religious leader, which later transformed into Dersim.[12]

History

Antiquity

This region was known as Ishuva in the 2000s BC. As a result of the struggle of the Ishuva Kingdom, which was established by the Hurrians in the region, with the Hittites, the region came under the rule of the Hittites in the 1600s BC. Then, it came under the domination of the Urartians and formed the westernmost part of the country of Urartu. After that, it was ruled by Medes and the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and after that it was ruled by Alexander the Great, king of Macedon.[13]

Ottoman Empire rule

Although the presence of Ottoman Empire was beginning to be felt in the region after Mehmed II the Conqueror defeated the Aq Qoyunlu in 1473, its incorporation into Ottoman lands took place after the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, during the reign of Selim the Grim. However, the harsh and rugged geographical structure of the region helped preserved its autonomy, keeping the control of the region away from the centralized government. The people of Dersim displayed rebellious attitudes during the weak periods of the central administrations.[13] Various Armenian and Alevi Kurdish rebellions took place in the region in 1877, 1885, 1892, 1907, 1911, 1914 and 1916.[13]

In Turkey

With the abolition of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey became the owner of the region. It was originally named Dersim Province (Dersim vilayeti), then demoted to a district (Dersim kazası) and incorporated into Elazığ Province in 1926.[14] In 1935, the Tunceli Law was passed, which established a state of emergency in the region, changed its name to Tunceli and made it a separate province consisting of the Nazımiye, Hozat, Mazgirt, Pertek, Ovacık, and Çemişgezek districts of Elazığ Province and the Pülümür District of Erzincan Province.[15][16][17][18] In January 1936, the Fourth Inspectorate-General (Umumi Müfettişlik, UM) was created, which spanned the provinces of Elazığ, Erzincan, Bingöl and Tunceli and was governed by a Governor-Commander, who had the authority to evacuate whole villages and resettle them in other regions.[19] This effectively established military rule in those provinces, and significant military infrastructure was established in the region.[16] Judicial guarantees such as the right to appeal were suspended, and the Governor-Commander had the right to apply the death penalty, whereas normally this would have to be approved by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey.[19] In 1937–1938, the Dersim rebellion took place in Tunceli Province and the adjacent regions, which resulted in the massacre of 30,000 Kurds and displacement of tens of thousands of inhabitants of the region by Turkish forces.[16] In 1946 the Tunceli Law was abolished and the state of emergency removed but the authority of the Fourth UM was transferred to the military.[19] Some of the deported families were allowed to return home.[20] The Inspectorates-General were dissolved in 1952 during the government of the Democrat Party.[21]

Since the 1970s, Tunceli Province has been a stronghold for insurgent groups such as the Communist Party of Turkey/Marxist–Leninist and the Kurdistan Workers' Party.[22]

Name changes

Before and after the Dersim rebellion, any villages and towns deemed to have non-Turkish names were renamed and given Turkish names in order to suppress any non-Turkish heritage.[23][24][25] During the Turkish Republican era, the words Kurdistan and Kurds were banned. The Turkish government had disguised the presence of the Kurds statistically by categorizing them as Mountain Turks.[26][27]

Linguist Sevan Nişanyan estimates that 4,000 Kurdish geographical locations have been changed (both Zazaki and Kurmanji).[28] Prior to the name changes, Many villages in Tunceli had recognizably Armenian names, often in corrupted forms.[8][29] The people of Tunceli have been actively fighting to get their province reverted to its old Kurdish name "Dersim". Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) claimed they are working on what it called a “democratization package” that includes the restoration of the Kurdish name of the eastern province of Tunceli back to Dersim in early 2013, but there has been no updates or news of it since then.[30] The local authority decided to call it Dersim in May 2019, while the Governor said it was against the law to call it Dersim.[31]

Demographics

.jpg.webp)

Tunceli Province has the lowest population density of any province in Turkey, at just 11 inhabitants/km2.

Language

In 1927, Tunceli's language distribution was 69.5% Kurmanji Kurdish and Zazaki, 29.8% Turkish and 0.74% Armenian.[32] Kurmanji Kurdish is the main dialect around Pertek, while Zazaki is spoken in Hozat, Pülümür, Ovacık and Nazımiye. Both Kurmanji and Zaza are spoken in Tunceli town and Mazgirt.[33]

Zazas/Alevis

The majority of Dersim's population are Zaza Kurds, many of whom practice Kurdish Alevism.[5] The Zazas migrated into Dersim during the 10th-12th centuries, probably originating from the Daylam region of northern Iran.[34] Today, the Dersim region is the heartland and sacred land of Kurdish Alevis.[35] The region's isolation has insulated it from the influence of Turkey's dominant Sunni sect of Islam, helping to keep its unique Alevi character relatively pure.[36]

Armenians of Dersim

Dersim had a large Armenian population prior to the Armenian genocide, with one estimate placing it at 45 percent of the total population of the region.[37] The districts of Mazgirt, Nazımiye and Çemişgezek had large Armenian populations during the Ottoman period.

The region is home to the ruins of a number of Armenian monasteries and churches, such as St. Karapet Monastery, which remains an object of reverence for Alevi Zaza-Kurds in Dersim today.[8][37] The Armenians and Alevi Zaza-Kurds of the region had generally good relations.[8][37] During the Armenian genocide, many of the Kurds of Dersim saved thousands of Armenians by hiding them or helping them reach the positions of the Russian army.[37] Some of the region's Armenian inhabitants that managed to survive converted to Alevism, and an unknown number of inhabitants of the province today have Armenian roots.[37][38] Distinctly Armenian settlements continued to exist in parts of Dersim until the massacre of 1938, after which the remaining Armenians completely assimilated into the Alevi Kurdish population.[38] An organization called Union of Dersim Armenians has been founded in Turkey by people from Dersim seeking to reconnect with their Armenian identity.[39]

| Muslim[lower-alpha 1] and Armenian population of the region according to Ottoman censuses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Muslims | Armenians | Notes |

| 1881/82–1893[40] | 41,089 (75.33%) | 13,050 (23.92%) | – |

| 1906/7[41] | 56,266 (81.19%) | 12,591 (18.16%) | 9,167 "Armenians", 3,424 "Armenian Catholics" |

| 1914[42] | 65,976 (82.39%) | 13,825 (17.26%) | 13,367 "Armenians", 458 "Armenian Catholics" |

Politics

In the municipal elections held in March 2019, Fatih Mehmet Maçoğlu was elected mayor of Tunceli municipality with 32% of the votes cast (Maçoğlu had previously been elected mayor of Ovacık in 2014).[43] He ran as the candidate of the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP), making him the first communist mayor of a municipality in Turkey.[44] In his first year in office, he has established free public transport in parts of the city. The development of industrial and agricultural cooperatives, which are meant to tackle unemployment, has already begun.[45]

Tunceli recorded the strongest "No" vote at 80.42% during the 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum. Previously, the province had recorded the strongest "No" vote at 81.02% during the 2010 Turkish constitutional referendum.

The province is a stronghold for pro-Kurdish parties as well as the Republican People's Party.

June 2015

| Party | Votes | % | +/– | Seats | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peoples' Democratic Party | 32,281 | 60.94 | new | 2 | +2 | |

| Republican People's Party | 10,906 | 20.59 | –36.91 | 0 | –2 | |

| Justice and Development Party | 5,631 | 10.63 | –5.10 | – | – | |

| Nationalist Movement Party | 3,131 | 5.91 | +3.78 | – | – | |

| Other | 1,026 | 1.94 | – | – | ||

| Total | 52,975 | 100.00 | – | 2 | – | |

| Valid votes | 52,975 | 98.63 | ||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 736 | 1.37 | ||||

| Total votes | 53,711 | 100.00 | ||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 63,614 | 84.43 | ||||

November 2015

| Party | Votes | % | +/– | Seats | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peoples' Democratic Party | 27,882 | 56.42 | –4.52 | 1 | +1 | |

| Republican People's Party | 14,094 | 28.52 | +7.93 | 1 | –1 | |

| Justice and Development Party | 5,837 | 11.81 | +1.18 | – | – | |

| Nationalist Movement Party | 1,292 | 2.61 | –3.30 | – | – | |

| Other | 315 | 0.64 | – | – | ||

| Total | 49,420 | 100.00 | – | 2 | – | |

| Valid votes | 49,920 | 98.90 | ||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 554 | 1.10 | ||||

| Total votes | 50,474 | 100.00 | ||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 62,608 | 80.62 | ||||

2018

| Party | Votes | % | +/– | Seats | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peoples' Democratic Party | 28,219 | 52.07 | –4.35 | 1 | 0 | |

| Republican People's Party | 14,358 | 26.49 | –2.03 | 1 | 0 | |

| Justice and Development Party | 7,228 | 13.34 | +1.53 | – | – | |

| Nationalist Movement Party | 3,019 | 5.57 | +2.96 | – | – | |

| Good Party | 849 | 1.57 | new | – | – | |

| Other | 521 | 0.96 | – | – | ||

| Total | 54,194 | 100.00 | – | 2 | – | |

| Valid votes | 54,194 | 97.74 | ||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 1,255 | 2.26 | ||||

| Total votes | 55,449 | 100.00 | ||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 64,290 | 86.25 | ||||

Education

Tunceli University was established on May 22, 2008.[46] Tunceli is famous for excellent rankings in National Education statistics.[47]

Places of interest

Tunceli is known for its old buildings such as the Çelebi Ağa Mosque,[48] Elti Hatun Mosque,[49] Mazgirt Castle,[50] Pertek Castle,[51] and the Derun-i Hisar Castle.[52][53]

Notable people

.jpg.webp)

- John I Tzimiskes (925–976)[54] - Byzantine emperor between 969 and 976

- Seyid Riza (1863–1937) - Alevi Zaza-Kurdish political leader of the Alevi Zaza-Kurds of Dersim, a religious figure and the leader of the Dersim movement in Turkey during the 1937–1938 Dersim Rebellion

- Nuri Dersimi (1893–1973) - Kurdish nationalist writer, revolutionary and intellectual

- Aurora Mardiganian (1901–1994) - Armenian author, actress, and a survivor of the Armenian genocide

- Vazken Andréassian (1903–1995) - Armenian engineer, author, and a survivor of the Armenian genocide

- Andranik Andréassian (1909–1996) - Armenian author, editor, and a survivor of the Armenian genocide

- Sait Kırmızıtoprak (1935–1971) - Kurdish nationalist writer and revolutionary

- Kemal Burkay (1937) - Kurdish writer and politician

- Kamer Genç (1940–2016) - Turkish politician

- Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (1948) - economist, retired civil servant, social democratic politician and leader of the Republican People's Party

- Mehmet Ali Eren (1951) - Kurdish politician

- Ali Haydar Kaytan (1952–2021) - Kurdish militant, co-founder of the Kurdistan Workers' Party

- Gülşen Aktaş (1957) - educator and social worker of Kurdish origin

- Hıdır Aslan (1958–1984) - Kurdish rebel

- Sakine Cansız (1958–2013) - Kurdish activist, co-founder of the Kurdistan Workers' Party

- Hamide Akbayir (1959) - German politician of Kurdish descent

- Edibe Şahin (1960) - Kurdish politician, former mayor of the municipality of Tunceli

- Hüseyin Kenan Aydın (1962) - German politician of Kurdish descent

- Hasan Saltık (1964) - Turkish record producer of mixed Turkish and Kurdish descent

- Ferhat Tunç (1964) - Kurdish singer, songwriter and musician

- Hozan Diyar (1966) - Kurdish singer

- Alican Önlü (1967) - Kurdish politician

- Fatih Mehmet Maçoğlu (1968) - Kurdish politician, currently the mayor of the municipality of Tunceli

- Hüseyin Aygün (1970) - Zaza-Kurdish lawyer and politician

- Kenan Engin (1974) - German-Kurdish political scientist

- Nilüfer Gündoğan (1974) - Dutch politician of Kurdish descent

- Aynur Doğan (1975) - Kurdish singer and songwriter

- Hülya Oran (1978) - Kurdish militant, one of leaders of Kurdistan Workers' Party and is the co-chair of the Kurdistan Communities Union

- Volga Sorgu (1981) - actor of Zaza-Kurdish descent

Originating from Tunceli

- Turgut Özal (1927–1993)[55][56] - 8th president of Turkey, he was of mixed Turkish and Kurdish descent

- Gültan Kışanak (1961)[57] - Kurdish journalist, author and politician

- Yıldız Tilbe[58] (1966) - singer of Kurdish descent

- Gülnaz Karataş (1971-1992) - Kurdish female fighter

- Dilan Yeşilgöz-Zegerius (1977) - Dutch politician of Kurdish descent, current Minister of Justice and Security in Netherlands

- Zuhal Demir (1980)[59] - Belgian lawyer and politician of Kurdish origin, current Flemish minister of Environment, Justice, Tourism and Energy

- Fırat Çelik (1981) - German-Turkish actor of Zaza-Kurdish descent

References

- "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- Area codes page of Turkish Telecom website Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- "Türkiye Mülki İdare Bölümleri Envanteri". T.C. İçişleri Bakanlığı (in Turkish). Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Watts, Nicole F. (2010). Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey (Studies in Modernity and National Identity). Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-295-99050-7.

- "Kurds, Kurdistān". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2 ed.). BRILL. 2002. ISBN 9789004161214.

- "İl ve İlçe Yüz ölçümleri". General Directorate of Mapping. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- "Munzur Valley National Park | National Parks Of Turkey". www.nationalparksofturkey.org. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- Arakelova, Victoria; Grigorian, Christine. "The Halvori Vank': An Armenian Monastery and a Zaza Sanctuary". academia.edu. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "The Massacre in Dersim Still Haunts Kurds in Turkey". jacobin.com. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- Korkmaz, M. (2012). Deylem’den Dersim’e Dersimliler. Ankara: Alter Yayıncılık, pp. 164–169. Archived from the original on 2022-05-04.

- "Daranaghi". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 3. 1977. p. 311.

- Halajyan, Gevorg (1973). Dersimi hayeri azgagrutʻyuně, masn A [Ethnography of the Dersim Armenians, part I] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Haykakan SSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun. pp. 249–250.

- Tuncel 2012, pp. 380–381.

- Album of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey Archived 2013-08-01 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 1, p. XXII, Dersim İli, 26.06.1926 tarih ve 404 sayılı Resmi Ceride'de yayımlanan 30.5.1926 tarih ve 877 sayılı Kanunla ilçeye dönüstürülerek Elazıg'a bağlanmıştır.

- "Hükümet Konağı Tarihçe". tunceli.gov.tr. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2016-01-19). "Dersim Massacre, 1937-1938". www.sciencespo.fr. Retrieved 2022-05-06.

- Kanun No. 2885, Resmî Gazete, 4 January 1936.

- "İl İdaresi ve Mülki Bölümler Şube Müdürlüğü İstatistikleri - İl ve İlçe Kuruluş Tarihleri" (PDF) (in Turkish). p. 81. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Bayir, Derya (2016-04-22). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-1-317-09579-8.

- McDowall, David (2007). A Modern History of the Kurds. London and New York: I. B. Tauris. pp. 105, 209. ISBN 9781850434160. OCLC 939584596.

- Fleet, Kate; Kunt, I. Metin; Kasaba, Reşat; Faroqhi, Suraiya (2008-04-17). The Cambridge History of Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3.

- Dinc, Pinar; Eklund, Lina; Shahpurwala, Aiman; Mansourian, Ali; Aturinde, Augustus; Pilesjö, Petter (2021-08-01). "Fighting Insurgency, Ruining the Environment: the Case of Forest Fires in the Dersim Province of Turkey". Human Ecology. 49 (4): 481–493. doi:10.1007/s10745-021-00243-y. ISSN 1572-9915. S2CID 237770099.

- Nişanyan 2011, p. 14.

- Tunçel 2000, p. 1.

- T.C İçişleri Bakanlığı İller İdaresi Genel Müdürlüğü (1968). "Köylerimiz".

- Hooglund 1996, p. 95.

- Bartkus 1999, p. 91.

- Nişanyan 2011, p. 54.

- Gasparyan, H. H. (1979). "Dersim (Patmaazgagrakan aknark)" [Dersim (historical-ethnographical outline)] (PDF). Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). 2: 195–210. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

- "After 78 years, Turkey to restore Tunceli’s original name". Today's Zaman. (in Turkish). "Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) is working on what it called a “democratization package” that includes the restoration of the Kurdish name of the eastern province of Tunceli. The original name of the province was Dersim and was changed to Tunceli in 1935."

- "A short history of Turkification: From Dersim to Tunceli". Ahval. (in Turkish). "The local authority in Tunceli in eastern Turkey decided this month to call the city and the province by its Kurdish name–Dersim–saying the Turkish name, which means bronze fist, did not represent the culture, history or religious beliefs of an area often at odds with central government."

- Sertel, Savaş (2016-01-31). "TÜRKİYE CUMHURİYETİ'NİN İLK GENEL NÜFUS SAYIMINA GÖRE DERSİM BÖLGESİNDE DEMOGRAFİK YAPI". Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 24 (1). doi:10.18069/fusbed.82073. ISSN 1300-9702.

- Malmîsanij, Mehemed (1988). "Dımıli ve Kurmanci Lehçelerinin Köylere Göre. Dağılımı". Berhem (in Kurdish and Turkish). 3: 62–67.

- "DIMLĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2021-09-22.

- Gültekin (2019), p. 4.

- Benanav, Michael (26 June 2015). "Finding Paradise in Turkey's Munzur Valley". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Hakobyan, T. Kh.; Melik-Bakhshyan, St. T.; Barseghyan, H. Kh. (1988). Hayastani ev harakitsʻ shrjanneri teghanunneri baṛaran [Dictionary of toponymy of Armenian and adjacent territories] (in Armenian). Vol. 2. Yerevan: Yerevan State University. pp. 93–94.

- Kharatyan, Hranush (2014-06-25). "The search for identity in Dersim Part 2: the Alevized Armenians in Dersim". repairfuture.net. Archived from the original on 2022-05-04.

- Abrahamyan, Gayane (2015-04-23). "Turkey's Armenians Rediscover Their Identity". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- Karpat 1985, p. 144, Ottoman General Census of 1881/82-1893 (continued), see the Hozat (Dersim) and Mazgirt.

- Karpat 1985, p. 164, Summary of Census of Ottoman Population, 1906/7 (continued), see the Dersim.

- Karpat 1985, p. 182, Summary of Ottoman Population, 1914 see the Dersim, Çemişgezek, Çarsancak, Ovacık, Nazımiye and Mazgirt.

- "Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) wins Dersim province in local elections". Liberation. March 31, 2019. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- Malzahn, Philip (April 1, 2019). "TKP gewinnt in Dersim". Neues Deutschland. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- Ashly, Jaclynn (February 3, 2020). "The Communist Mayor of Dersim". The Indypendent. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- "Tunceli University Signs Protocol with 4 American Universities". Turkish Daily Mail. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Eğitim sıralamasında Tunceli birinci". 11 December 2018.

- "ÇELEBİ AĞA CAMİİ". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Pushover Analysis of Historical Elti Hatun Mosque" (PDF). Semantic Scholar. S2CID 194452128. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Sinclair, T. A. (31 December 1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-904597-78-0.

- "Pertek Kalesi". Archived from the original on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2016-10-19.

- "Derun-i Hisar (Sağman) Kalesi". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- "DERUN-İ HİSAR (SAĞMAN) KALESİ". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Çemişgezek" in The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names, 2005, by John Everett-Heath, Oxford University Press.

- "Çemişgezek'e bir gelen geri dönmek istemiyor". Sabah. (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2023. "8. Cumhurbaşkanı Turgut Özal'ın annesi Hafize Özal, Çemişgezek Mezire Köyü doğumlu."

- "Turgut Özal'ı rahmetle anıyoruz". Yeni Akit. (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2023. "Babası Malatya/Çırmıktı'lı Ünlüoğulları'ndan banka memuru Mehmet Sıddık Özal, annesi ise Tunceli Çemişgezekli, ilkokul öğretmeni Hafize Hanım (d. 1906 - ö. 1988) olan Turgut Özal kısmen Kürt kökenlidir."

- "Gültan Kışanak Kimdir?". Bianet. (in Turkish). 9 February 2023. "Ailesi zamanında Dersim'den göçerek Elazığ'ın merkez köylerinden Sünköy'e yerleşmiş bulunan Ağuce aşiretine mensuptur."

- "Star'daki Yıldız Tilbe'nin Programında Türk-Kürt Gerginliği...". Haber Vitrini. (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2023. "Programın ilerki bölümlerinde Yıldız Tilbe, “Ulaştırma Bakanından uyarı gelmiş. Benim anam Tuncelili, hem Zaza hem Kürt, babam Ağrılı Kürt. Ben bu topraklarda doğdum, büyüdüm. Kürt neyse benim için Türk de odur, Laz da odur, Çerkez de odur. Hiç bir farkı yoktur birbirinden asla” dedi."

- "Belçika’nın Kürt asıllı bakanı Zuhal Demir tehdit edildi". Ahval. (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2023. "Tunceli ve Elazığ kökenli, maden işçisi bir babanın üçüncü çocuğu olan Zuhal Demir, 12 Mart 1980'de Belçika'nın Genk kentinde dünyaya geldi."

Sources

- Gültekin, Ahmet Kerim (2019). Kurdish Alevism: Creating New Ways of Practicing the Religion (PDF). University of Leipzig.

- Karpat, K.H. (1985). Ottoman population, 1830-1914: demographic and social characteristics. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299091606.

- Tunçel, H. (2000). "Türkiye'de İsmi Değiştirilen Köyler" [Changed Villages in Turkey]. Journal of Social Sciences (in Turkish). Firat University. 10 (2).

- Tuncel, Metin (2012). "Tunceli". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Vol. 41. pp. 380–381.