Music of Detroit

Detroit, Michigan, is a major center in the United States for the creation and performance of music, and is best known for three developments: Motown, early punk rock (or proto-punk), and techno.[1]

The Metro Detroit area has a rich musical history spanning the past century, beginning with the revival of the world-renowned Detroit Symphony Orchestra in 1918. The major genres represented in Detroit music include classical, blues, jazz, gospel, R&B, rock, pop, punk, soul, electronic music, and hip hop. The greater Detroit area has been the birthplace and/or primary venue for numerous platinum-selling artists, whose total album sales, according to one estimate, had surpassed 40 million units by 2000.[2][3] The success of Detroit-based rappers quadrupled that figure in the first decade of the 2000s.[4][5]

Historical background

The Detroit area's diverse population includes residents of European, Middle Eastern, Latino, Asian and African descent, with each group adding its rich musical traditions.[6] The African-American population in particular contributed greatly to the musical legacy of Detroit in almost all genres. During the 1930s and 1940s, the near-east side neighborhoods known as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley became a major entertainment district, drawing nationally known blues singers, big bands, and jazz artists – such as Duke Ellington, Billy Eckstine, Pearl Bailey, Ella Fitzgerald, and Count Basie.

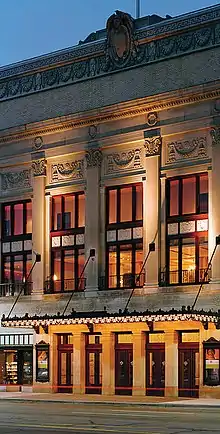

During the 1940s, many of the same jazz acts also performed nearby at Orchestra Hall, which had been renamed the Paradise Theatre in honor of the Paradise Valley district.[7] Eventually urban renewal projects during the late 1950s and early 1960s demolished Black Bottom and replaced it with a freeway and the neighborhood centered on Lafayette Park, (designed by Mies van der Rohe and others).[8] As Black Bottom was disappearing, the nascent Motown label was beginning to build an eventual empire on West Grand Boulevard. From the 1960s on, the nightclubs and music venues in Detroit could be found dispersed throughout the city and catering to all genres; from jazz at Baker's Keyboard Lounge on the northern border of the city, to rock and roll at the Grande Ballroom on the west side.[9][10]

Blues

The genesis of Blues music in Detroit occurred as a result of the first wave of the Great Migration of African-Americans from the Deep South. In the 1920s, Detroit was home to a number of pianists who performed in the clubs of Black Bottom and played in the Boogie-woogie style of blues, such as Speckled Red (Rufus Perryman), Charlie Spand, William Ezell, and most prominently, Big Maceo Merriweather. As Detroit had no established recording scene at the time, all of these players eventually migrated to Chicago to record for various labels. Spand reminisced about his time in Detroit while playing on the 1929 Blind Blake single "Hastings Street".

During the 1920s, Detroit was also host to most of the famous singers of the classic female blues, including "The Queen of the Blues" Mamie Smith, "The Mother of the Blues" Ma Rainey, "The Empress of the Blues" Bessie Smith, "The Uncrowned Queen of the Blues" Ida Cox, "The Queen of the Moaners" Clara Smith, "The Famous Moanin' Mama" Sara Martin, and Ethel Waters.[11] Most of these performers visited Detroit on tour as part of the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA) circuit, playing primarily at the Koppin Theatre on the southern edge of Paradise Valley.[11]

The Koppin was the premier venue for Detroit's black musical community throughout the 1920s. It ceased operation in 1931, a casualty of the Great Depression. The decade of the 1930s saw a dearth of blues music in Detroit, which did not see a resurgence until the second wave of the Great Migration hit during the 1940s, bringing artists such as John Lee Hooker to Detroit to work in the factories of the Arsenal of Democracy.

These artists brought with them a style of blues music rooted in the Mississippi Delta region. Though not strictly a Delta blues musician, Hooker was born in the epicenter of the tradition, in Clarksdale, Mississippi, and migrated to Detroit in 1943. He scored an early hit with his first single Boogie Chillen, and began a long career that made him the most prominent and successful of the Detroit blues players of the post-war period, as well as the most-recorded, with over 500 tracks to his credit.[12] Teaming up with Hooker in the late 1940s was the guitarist and harmonica player Eddie "Guitar" Burns, who played on several Hooker tracks and performed regularly on the Detroit blues scene. Another sideman of Hooker was Eddie Kirkland, who played second guitar for him in Detroit and on tour from 1949 to 1962, and later went on to a long solo career.

Other notable musicians on the 1950s blues scene were the singers Alberta Adams and singer/guitarists Doctor Ross, Baby Boy Warren, Johnnie Bassett, Sylvester Cotton, Andrew Dunham, Calvin Frazier, Mr. Bo, John Brim and Louisiana Red; percussionist Washboard Willie; harmonica players Big John Wrencher, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Little Sonny (Willis), and Grace Brim (who also sang and played drums); and pianists Joe Weaver and Boogie Woogie Red. Also of note were singer Johnnie Mae Matthews and singer/guitarist Bobo Jenkins, both of whom started their own labels, Northern Records and Big Star Records, respectively.[11]

It was the emergence of local record labels in Detroit in the 1940s and 1950s which helped the blues scene to flourish, compared to the 1920s, when blues artists generally emigrated to Chicago to record their music. Some small labels, including Staff, Holiday, Modern, and Prize Records, only existed for a brief time, while other labels experienced greater success.[13] The most prominent of the Detroit-based labels from this era was Fortune Records, and its subsidiary labels Hi-Q, Strate 8 and Blue Star, which ran from 1948 to 1970. Fortune released hundreds of recordings in many genres, including tracks by Hooker, Kirkland, Jenkins, Dr. Ross and Maceo Merriweather.[14]

Another important Detroit label from the period was Sensation Records, started by John Kaplan and Bernard Besman. In 1948, Besman recorded Hooker's seminal "Boogie Chillen" and ran the artistic side of the label until its demise in 1952.[11] Local entrepreneur Joe Von Battle was another key figure on the blues scene; in the back of his record shop on Hastings Street he recorded a number of blues acts that appeared on his JVB and Von record labels.[15]

The entertainment districts of Hastings Street and Paradise Valley were razed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the victims of urban renewal programs. This loss of music venues, along with the rise of Motown in Detroit and the popularity of rock and roll, led to the eventual demise of the Detroit blues scene in the late 1960s. Many Detroit-based musicians pursued their careers on tour elsewhere in the world, leaving only a few noteworthy artists to carry on the tradition. Among them were The Butler Twins, Clarence (guitar and vocals) and Curtis (harmonica), who emigrated to Detroit from Alabama in 1961, joining a long list of blues forebears who came to work in the automotive industry. Another transplant was the former classic female blues singer Sippie Wallace, who had moved to Detroit in 1929, but did not resume her blues singing career until 1966.

In the wake of the 1967 Detroit riot the local blues scene nearly died out, being salvaged only through the help of Mississippi Delta native Uncle Jessie White, pianist and harmonica player, who hosted weekend-long blues jams at his house for the next four years.[16] In 1973, the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival put on a "Music of Detroit" showcase, featuring a number of the older generation of blues artists, such as John Lee Hooker, Dr. Ross, Baby Boy Warren, Mr. Bo, Johnnie Mae Matthews, Eddie Burns, Bobo Jenkins, and Boogie Woogie Red. Shortly thereafter, the Chicago bluesman Willie D. Warren moved to Detroit, and spent the rest of his life performing on the blues scene in and around the city. Another transplant from Chicago in the 1970s was Johnny "Yard Dog" Jones, who played in Detroit for the next four decades.[13] Jones became part of a strong tradition of Detroit harp players, including Harmonica Shah, who also came on the scene in the 1970s.

In the late 1980s, one of the most prominent Detroit blues players was Jim McCarty. After successful stints with the Buddy Miles Express and the rock bands Cactus and The Rockets, McCarty joined the Detroit Blues Band, with whom he cut two records in the 1990s, after which he formed his own blues band, Mystery Train. Another artist to appear in the late 1980s was the blues singer and Detroit native Thornetta Davis, who cut her first solo album in 1996. Davis has won numerous local awards as a blues artist and vocalist, and continues to perform locally and nationally.

The late 1990s saw the emergence of The White Stripes, led by guitarist and Detroit native Jack White. Although ostensibly a garage rock band, a significant amount of their material consisted of blues cover songs, and the band is considered a proponent of the punk blues and blues rock genres.[17][18][19]

Gospel

Detroit has produced some of the most famous gospel singers in past decades. In the 1940s, Oliver Green formed The Detroiters, who became one of the most popular Gospel groups of their era. In the 1950s, Laura Lee and a young Della Reese began their long and distinguished careers coming out of the Meditations Singers, indisputably the premier Detroit-based, female gospel group of that era. Theirs was the first Motor City act to introduce instrumental backing to traditional a cappella vocals. Della joined the ranks of the gospel elite in Detroit, while Mattie Moss Clark is believed to be the first to introduce three part harmony into gospel choral music.

In the 1960s, the Reverend CL Franklin found success with his recorded sermons on Chess Record's gospel label and with an album of spirituals recorded at his New Bethel Baptist Church included the debut of his young daughter, Grammy Award winner Aretha Franklin.[2]

In the 1980s, the Winans dynasty produced Grammy winners Cece and BeBe Winans. Other notable gospel acts include J Moss, Bill Moss, Jr., The Clark Sisters, Rance Allen Group, Vanessa Bell Armstrong, Thomas Whitfield, Byron Cage and Fred Hammond.[20]

Jazz

As the Jazz Age began, Detroit quickly emerged as an important musical center. Among the musicians who relocated to Detroit were drummer William McKinney, who formed the seminal big band McKinney's Cotton Pickers with the great arranger, bandleader and composer, Don Redman. Detroit's musical prominence continued through the 1950s.[11] Musicians from Detroit who achieved international recognition include Elvin Jones, Hank Jones, Thad Jones, Howard McGhee, Tommy Flanagan, Lucky Thompson, Louis Hayes, Barry Harris, Paul Chambers, Yusef Lateef, Marcus Belgrave, Milt Jackson, Kenny Burrell, Ron Carter, Curtis Fuller, Julius Watkins, Hugh Lawson, Frank Foster, J. R. Monterose, Doug Watkins, Sir Roland Hanna, Donald Byrd, Kenn Cox, George "Sax" Benson, Sonny Stitt, Alice Coltrane, Dorothy Ashby, Roy Brooks, Phil Ranelin, Faruq Z. Bey, Pepper Adams, Tani Tabbal, Charles McPherson, Frank Gant, Billy Mitchell, Kirk Lightsey, Lonnie Hillyer, James Carter, Geri Allen, Rick Margitza, Kenny Garrett, Betty Carter, Sippie Wallace, Robert Hurst, Rodney Whitaker, Karriem Riggins, Major Holley and Carlos McKinney.

Other significant players who spent part of their career in Detroit include Benny Carter, Joe Henderson, Wardell Gray, Grant Green and Don Moye. As this list reflects, Detroit musicians were major contributors to the hard-bop and post-bop styles, especially in the rhythm sections that drove the classic groups of Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and contributions to the bands of Charles Mingus, Horace Silver and The Jazz Messengers.

Venues in Detroit today include The Hot Club of Detroit, founded 2003 at Wayne State University,[21] Cliff Bell's, Baker's Keyboard Lounge and The Dirty Dog Jazz Cafe.

Pop

Detroit has been the home to several well-known pop artists, including Margaret Whiting, Sonny Bono and Suzi Quatro, who may be best known for her role as Leather Tuscadero on the hit 1970s TV show Happy Days.[2] One of the most famous is Madonna. Although Madonna was born and spent her early summers in Bay City, she was raised outside of Detroit, in Rochester (about 35 miles from Detroit itself) and went to the University of Michigan on a dance scholarship. Several of Madonna's early hits were co-written by ex-boyfriend and fellow Detroit Native Stephen Bray.

Also during the 1980s, Detroit pop rockers Was (Not Was) breakthrough album What Up, Dog? spawned two Top 20 hits with the songs "Spy in the House of Love" and "Walk the Dinosaur."

1990s pop star Aaliyah (1979-2001) was raised in Detroit and graduated from the Detroit School of Arts. Aaliyah was also the niece of former Detroit politician Barry Hankerson and soul singer Gladys Knight.[2] She had several hit songs including the No. 1 hit "Try Again" in 2000.

Aaliyah was not the only Detroit School of Arts graduate to go on to musical success; since her graduation, Teairra Marí has enjoyed a successful career, including her hit single "Make Her Feel Good" in 2005.[22]

R&B/Soul

One of the highlights of Detroit's musical history was the success of Motown Records during the 1960s and early 1970s.[2] The label was founded in the late 1950s was founded by auto plant worker Berry Gordy, and was originally known as Tamla Records. As Motown, it became home to some of the most popular recording acts in the world, including Marvin Gaye, The Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross & The Supremes, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, The Four Tops, Martha Reeves & the Vandellas, Edwin Starr, Little Willie John, The Contours and The Spinners.[23][24]

Even before Motown, Detroit had an active R&B and soul community. In 1955, the influential soul singer Little Willie John made his debut, and throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, Detroit-based R&B label Fortune Records enjoyed success with Nolan Strong & The Diablos and their hit songs "The Wind", "Mind Over Matter", and "The Way You Dog Me Around". Smokey Robinson noted in his biography that Strong's high tenor was his biggest vocal influence. Strong is remembered on the 2010 album Daddy Rockin Strong: A Tribute to Nolan Strong & The Diablos – a tribute compilation that features current rock and roll bands covering Diablos songs. The album was compiled and released by The Wind Records and Norton Records.

In 1956, notable blues and R&B singer Zeffrey "Andre" Williams recorded a string of singles for Fortune, including the song "Bacon Fat." In 1961, Nathaniel Mayer & Fabulous Twilights hit the charts with "Village of Love," which became one of Fortune's top-selling singles. Mayer recorded a string of popular 45s for Fortune, even once performing on Dick Clark's American Bandstand.

In 1959, The Falcons (featuring Wilson Pickett and Eddie Floyd) had a hit with "You're So Fine". Also that year, Jackie Wilson had his first hit with "Reet Petite", which was co-written by a young Berry Gordy Jr. The Volumes had a hit single in 1962 for Chex Records with the single "I Love You". That same year singer/songwriter Barbara Lewis had a hit with the single "Hello Stranger.", while Gino Washington had cross-racial appeal and achieved Midwest hits in 1963 and 1964 with "Out of This World" and "Gino Is a Coward".

Several other Detroit artists became nationally known without the help of Motown. Perhaps the best known of such artists was Aretha Franklin. Other non-Motown acts included The Capitols with their 1966 hit "Cool Jerk" and Darrell Banks with "Open the Door to Your Heart". The following year, J.J Barnes had his biggest hit with "Baby Please Come Back Home".

In 1967, longtime back room barbershop doo wop group The Parliaments, featuring George Clinton, scored a hit with "I Wanna Testify" for Revilot Records, and marked the beginning of funk in mainstream R&B. In 1968, Clinton changed the name of The Parliaments in 1968 to Funkadelic following a legal dispute with Revilot, but in 1970 reclaimed the rights and renamed the group as simply "Parliament". Eventually the group became known as simply P-Funk which is short for Parliament-Funkadelic.

In 1967, Berry Gordy purchased what is now known as Motown Mansion in Detroit's Boston-Edison Historic District.[25] Motown Records relocated to the West coast 1972, yet Detroit remained an important center of R&B with acts such as Freda Payne, The Floaters, Enchantment, Ray Parker Jr.; both solo and with his group Raydio, One Way, Oliver Cheatham, Cherrelle, The Jones Girls, Anita Baker, and BeBe & CeCe Winans.

In 1969 The Flaming Ember had several hits for Hot Wax Records, a Detroit-based record label created in 1968 by the Holland/Dozier/Holland song writing team after they left Motown Records. The following year Chairmen of the Board had the first hit for Invictus with "Give Me Just a Little More Time."

During the disco craze of the late 1970s, Detroit artists had several dance hits. In 1975, Stevie Wonder's drummer Hamilton Bohannon had a hit with "Foot Stompin' Music", while Donald Byrd & The Blackbyrds infused jazz with dance friendly elements that produced the song "Change (Makes You Wanna Hustle)". In 1977 Brainstorm & C. J. & Company each had soul driven dance hits.

In 1978, George Clinton's bass player Bootsy Collins had a top charting hit with Bootzilla. George Clinton and his band Parliament-Funkadelic is often cited as being a direct influence on the future Detroit Techno scene that emerged in the early 1980s.

Rock

1950s

Detroit has a long and rich history associated with rock and roll. In 1954 Hank Ballard & the Midnighters crossed over from the R&B charts to the pop charts with "Work With Me, Annie". The song nearly broke into the elite top 20 despite being barred from airplay on many stations due to its suggestive lyrics. In 1955, Detroit-native Bill Haley ushered in the rock and roll era with the release of "Rock Around The Clock".[26]

In the late 1950s rockabilly guitarist Jack Scott had a string of top 40 hits. First, in 1957 with "Leroy", then in 1958 with the hits "My True Love" and "With Your Love" and then twice again in 1959 with the hits "Goodbye Baby" and "The Way I Walk." Scott was one of the first musicians to marry country music's melodic song craft to the dangerous, raw power of rock and roll.[26]

1960s

In 1959 Hank Ballard & The Midnighters had a minor hit with their b-side song "The Twist". A cover by Philadelphia native Chubby Checker followed in 1960. His single became a smash hit, reaching No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and started a national dance craze. Also in 1960, Jack Scott had his final top 10 hits with "What in the World's Come Over You" and "Burning Bridges".

The following year, rocker Del Shannon had his own No. 1 hit in March 1961 with the song "Runaway". This was followed by the top 10 hits "Hats Off to Larry" in June 1961 and "Little Town Flirt" in 1962. In 1964, Detroit's one-hit wonders The Reflections had their own Top 10 hit single with "(Just Like) Romeo and Juliet".[26]

By 1964, teen clubs around Metro Detroit such as the Fifth Dimension in Ann Arbor and the Hideout off of 8 Mile Road and Harper Road, were a hotbed for young and promising garage rock bands such as The Underdogs, The Fugitives, Unrelated Segments, Terry Knight and the Pack (which featured Don Brewer), ASTIGAFA (which featured a young Marshall Crenshaw), The Lords (featuring a young Ted Nugent), The Pleasure Seekers (which featured a young Suzi Quatro), Four of Us and the Mushrooms (which both featured Glenn Frey), Sky (which featured a young Doug Fieger), and blue-eyed soul rockers the Rationals.[26]

In 1965 Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels had a national top 10 hit with "Jenny Take A Ride!" and then again the following year in 1966 with "Devil With A Blue Dress On"/"Good Golly, Miss Molly". Also in 1966, Flint's Question Mark & the Mysterians had a No. 1 hit with "96 Tears". In 1967, Detroit blues-rock outfit the Woolies had a regional smash hit with the Bo Diddley song "Who Do You Love?".[26] Tommy James and the Shondells had several top 40 hits including "I Think We're Alone Now" and "Crimson and Clover".

In the late 1960s, two well-known high-energy rock bands emerged from Detroit – the MC5 and Iggy and the Stooges.[27][28] These two bands laid the groundwork for the future punk and hard rock movements in the late 1970s.[29][30][31] Other notable bands from this time frame included Alice Cooper, The Amboy Dukes (featuring Ted Nugent), The Bob Seger System, Frijid Pink, SRC, The Up, The Frost (featuring Dick Wagner), Popcorn Blizzard (featuring Meat Loaf), Cactus and the soulful sounds of Rare Earth and The Flaming Ember. Much of the music scene during this time was centered around the legendary Grande Ballroom and its owner Russ Gibb.[32]

In 1969 a magazine based in and around Detroit known as CREEM: "America's Only Rock 'n' Roll Magazine," was started by Barry Kramer and founding editor Tony Reay. CREEM is known as the first publication to coin the words "punk rock" and "heavy metal" and featured such famous editors such as Rob Tyner, Jaan Uhelszki, Patti Smith, Cameron Crowe, and Lester Bangs, who is often cited as "America's Greatest Rock Critic,".

Detroit in the 1960s also contributed to the national folk scene with southeastern Michigan native Phil Ochs, who gained fame as a Greenwich Village folk artist; Detroit was also home for a few years to the then unknown Joni Mitchell. Fortune Records also released numerous "Hillbilly" Americana folk records in this period.

1970s

During the 1970s, several local Metro Detroit acts achieved national or international fame, including Bob Seger, Iggy Pop, Ted Nugent, Alice Cooper, Grand Funk Railroad, and Glenn Frey of Eagles.[2] Other local groups, like Brownsville Station and Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, enjoyed brief national exposure. Non-Detroit rock bands paid tribute to the city through such songs as "Detroit Rock City" by Kiss, "Detroit Breakdown" by The J. Geils Band and "Panic in Detroit" by David Bowie.

In the early 1970s, several new Detroit bands were formed out of earlier bands that had broken up. These acts included rock acts such as Sonic's Rendezvous Band (featuring Fred "Sonic" Smith of the MC5, Scott Morgan of The Rationals, Scott Asheton of The Stooges), the band simply called Detroit, which featured Mitch Ryder on vocals and Johnny "Bee" Badanjek on drums, The Rockets, which featured Jim McCarty on guitar and Badanjek on drums, and The New MC5 featuring Rob Tyner on vocals. Two groups from this period remained relatively obscure while they were together, achieving greater fame only decades later: Destroy All Monsters and Death. Destroy All Monsters featured artists Niagara, Mike Kelley, Carey Loren, and Jim Shaw as well as Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton in its later incarnation. Formed in 1971, Death is now recognized as the first all African American punk band. Rodriguez began his career in the early 1970s, and while an unknown in Detroit, gained a following in South Africa and Australia. Also during this time, Detroit area native Deniz Tek was creating the punk band Radio Birdman in Australia in the mold of classic Detroit rock bands of the MC5 and The Stooges.[32]

1980s and 1990s

During the 1980s & 1990s, metro Detroit rock bands that had minor to major attention and/or critical acclaim include The Romantics, The Gories, Kid Rock and his band Twisted Brown Trucker, The Dirtbombs, Outrageous Cherry, The Hentchmen, Electric Six, Sponge, The Verve Pipe, Big Chief, Discipline, Goober & the Peas, Robert Bradley's Blackwater Surprise, Adrenalin, His Name Is Alive, Majesty Crush, Brendan Benson, Demolition Doll Rods, The Sights, and ska-punk band The Suicide Machines.

The 1980s also saw Marshall Crenshaw from the Detroit suburb of Berkley, attain fame with his releases on Warner Bros. and an appearance as Buddy Holly in the film La Bamba. His 1981 recording, "Someday, Someway", made the Top 40 in both Billboard and Cash Box in 1982.

2000s and 2010s

During the 2000s & 2010s, metro Detroit rock bands that had minor to major success and/or critical acclaim include: The White Stripes, The Raconteurs, Uncle Kracker, The Von Bondies, Taproot, Pop Evil, Jack White, Greta Van Fleet, and I Prevail.[33]

Hardcore punk

The Detroit suburbs were the location of one of the first important hardcore punk scenes that swept underground America in the early 1980s. By the end of 1981 the new style sometimes known as "Midwest Hardcore" had exploded across North America and Detroit was one of several important regional centers fostering its spread.[34] Two of the earliest Suburban Detroit hardcore punk bands were the Grosse Pointe Woods, Michigan band The Holes and Grosse Pointe Park band Degenerates.[35]

The Detroit scene was not an isolated phenomenon but also the focus for a number of sister scenes throughout Michigan and northern Ohio. The major hardcore bands of this early regional scene included Lansing, Michigan's The Meatmen, Kalamazoo, Michigan's Violent Apathy,[36] Spite,[37] and The Crucifucks, Toledo, Ohio's Necros, and Detroit's Negative Approach.[38]

1980s–1990s

During this period, the Detroit hardcore scene become most important over the years for Touch and Go Records, which was started in Lansing, Michigan, in 1979 by Tesco Vee and Dave Stinson as a popular local fanzine and eventually became a hardcore record label in 1981. Touch and Go subsequently moved to Chicago.[39]

Many small clubs popped up hosting hardcore bands. The Golden Gate, The Falcon Lounge, the Freezer Theater, Kurt Kohls' Asylum, and The Hungry Brain (named after the club in the movie "The Nutty Professor"). A crucial venue for hardcore fans in Detroit was known as Clutch Cargo's, named after a limited-animation TV series. It featured such bands as Black Flag, Fear, X, and the Dead Kennedys, who played the venue while on tour, while the Necros, Negative Approach, L-Seven (not to be confused with L7) and other local and nearby regional bands also appeared. The venue was formerly located in a large, former athletic club in Detroit. As Clutch Cargo's often had shows for 18+ fans, many younger hardcore fans either never attended the site due to age, or even knew of it due to their tardy introduction to the subgenre.[34] Now the former club is a church called the Grace Gospel Fellowship.

The Hungry Brain, situated in a former second-hand store in Delray, Detroit, had been forced to relocate several times and by 1985 found a permanent home at a run-down old hall on Michigan Avenue deep in Detroit called[40] Graystone Hall. Bands that started at the Hungry Brain, like political hardcore stalwarts Forced Anger,[41] often opened for many West Coast touring punk bands, including 7 Seconds, T.S.O.L and Minor Threat, at the Graystone. The band published the fanzine, "Placebo Effect", which produced several compilation tapes featuring upstart punk bands from all over Michigan. Many Graystone gigs were captured by Back Porch Video, a video project of Dearborn public schools run by Russ Gibb (DJ of "Paul is Dead" rumor fame and previously known as the impresario of the Grande Ballroom) and aired on local public-access television cable TV.[34]

The band Cold As Life developed a loyal following right up to their demise in 2001, even surviving the murder of their frontman Rawn Beauty. Other important bands of that time period were the Almighty Lumberjacks of Death (A.L.D.), fronted by the charismatic and deep-voiced Jimmy Doom.[42]

Techno

Detroit has been cited as the birthplace of techno music.[43][44] Prominent Detroit Techno artists include Juan Atkins, Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, Carl Craig, and Jeff Mills. The template for a new style of dance music (that by the mid to late 1980s was being referred to as techno) was primarily developed by four individuals, Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May ("The Belleville Three"), and Eddie Fowlkes, all of whom attended high school together at Belleville High School, near Detroit, Michigan. By the close of the 1980s the four had operated under various guises: Atkins as Model 500, Flintstones, and Magic Juan; Fowlkes simply as Eddie "Flashin" Fowlkes; Saunderson as Reese, Keynotes, and Kaos; with May using the aliases Mayday, R-Tyme, and Rhythim Is Rhythim. There were also a number of joint ventures, the most commercially successful of which was the Atkins and Saunderson (with James Pennington) collaboration on the first Inner City single Big Fun. Prior to achieving notoriety the budding musicians, mix tape traders, and aspiring DJs found inspiration in Midnight Funk Association, an eclectic, 5-hour, late-night radio program hosted on various Detroit radio stations including WCHB, WGPR, and WJLB-FM from 1977 through the mid-1980s by DJ Charles "The Electrifying Mojo" Johnson.[45][46] Mojo's show featured heavy doses of electronic sounds from the likes of Giorgio Moroder, Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream alongside the funk of Parliament and the new wave sounds of the B-52s.[47]

Of the four individuals responsible for establishing techno as a genre in its own right, it is Juan Atkins who is recognized as the originator; indeed in 1995 American music technology publication Keyboard Magazine honored Atkins as one of "12 Who Count" in the history of keyboard music (this is remarkable considering Detroit techno was still relatively unknown in the United States at that time despite its notoriety in Europe). In the early 1980s Atkins began recording with musical partner Richard "3070" Davis (and later with a third member Jon-5) as Cybotron. This trio released a number of electro inspired tunes, the best known of which is "Clear". Eventually, Atkins started producing his own music under the pseudonym Model 500, and in 1985 he established the record label Metroplex. In the same year he released a seminal work entitled "No UFO's" which, in terms of its aesthetic values, is credited by many as the first Detroit techno production. Another earlier track that is often cited is A Number of Names' Sharevari.

Electro-disco tracks share with techno a dependence on machine-generated beats and dancefloor popularity. However, the comparisons remain contentious; as do the efforts to regress further into the past to find antecedents. The logical extension of this rationale entails a further regression: to the sequenced electronic music of Raymond Scott (The Rhythm Modulator, The Bass-Line Generator, and IBM Probe, being remarkable examples of techno-like music).[48]

Hip hop

Early Detroit hip hop (1980s)

In 1980, Detroit electro duo Cybotron formed; the group were a staple of the Electrifying Mojo, an influential FM radio personality who helped popularize hip hop music.[50] The same year, Detroit record store Future Funk Records opened on West Seven Mile Road, and an aspiring hip-hop emcee named Jerry Flynn Dale befriended the owner, Carl Mitchell, and convinced him to allow Dale to set up a makeshift stage in the store, play instrumentals and rap, signaling the beginnings of Detroit's hip-hop scene, as aspiring rappers would use the store to battle rap, test out new songs and sell their albums, until 1992, when the store closed.[51][52] Dale would initially produce hip-hop beats in his bedroom, before launching Def Sound Studios in Detroit in 1985.[51] Another important figure who helped shape Detroit hip-hop was DJ the Blackman, who, as a teenager, helped teen emcees develop their lyrical skills in his basement.[51] Additionally, Detroit radio disc jockey Billy T helped popularize hip-hop in Detroit through his programs Billy T's Basement Tapes and The Rap Blast, which exposed listeners to local developing emcees, helping to expand the genre's popularity in the city.[51] However, the growing popularity of the genre was not without problems, as rap shows in Detroit often ended in violence in the developing years of the city's local scene at concert venues such as Harpo's.[51]

The earliest successful Detroit rap act was the duo Felix & Jarvis, who released "The Flamethrower Rap" in 1983, utilizing large portions of the song "Flamethrower" by the J. Geils Band. However, it would take several years before more rap acts would come to prominence in Detroit. These would include Magic Juan & Normski and Prince Vince and the Hip Hop Force, both of which debuted in 1988, as well as Awesome Dre & The Hardcore Committee, Kaos & Mystro, Merciless Amir, Esham and Nikki D, who all debuted in 1989.[50] Detroit's Most Wanted and A.W.O.L. pioneered Detroit hardcore hip-hop and gangsta rap, respectively, while Prince Vince was one of the first rappers to sample the funk music of Detroit's Parliament-Funkadelic collective in his song "Gangster Funk", whose release predated the coining of the term G-funk by West Coast producer Dr. Dre.[51]

National breakthrough (1990s)

The early 1990s Detroit hip hop scene was the launching point for several prominent female rappers, including Nikki D., Smiley, and Boss.[50] MC Breed, who was originally from Flint, Michigan, launched his career in Detroit and would go on to national success with a G-funk sound influenced by West Coast hip-hop, while Awesome Dre became the first Detroit rapper to appear on Yo! MTV Raps and BET's Rap City.[50][51] The mid-90s would come to be known as Detroit hip-hop's "Golden Age". However, despite the city being predominantly African American, many of Detroit's most successful hip-hop acts have been white rappers.[50]

A thriving local hip hop scene developed with club parties at St. Andrew's Hall on Friday evenings and the following day, at the clothing store the Hip Hop Shop, emcee Proof hosted rap battles showcasing the skills of young, developing rap talents.[50] The Hip Hop Shop opened in 1993 and closed in 1997, before reopening under new management in 2005, where it stayed in business until 2014, when the store shut down again.[52] Not all Detroit rappers, however, developed their careers out of this battle rap scene, as Esham, Kid Rock and Insane Clown Posse all developed their own paths to success, before the Hip Hop Shop had even opened.[51][53][54][55] The Hip Hop Shop scene did, however, help a young Eminem develop his lyrical skills and flow. As M&M, he appeared on Bassmint Productions' single "Steppin' On To The Scene" in 1990. Two years later, he appeared in an acting performance in the music video for Champtown's single "Do-Da-Dippity".[50] The same year, Champtown, Chaos Kid and Eminem formed the group Soul Intent, releasing "What Color Is Soul" in 1992, followed by "Biterphobia" and "Fuckin' Backstabber" in 1995, the latter of which featured an appearance from rapper Proof.[50] Champtown released the album Check It the following year, in the same year Eminem released his debut album Infinite.[50] After being discovered by Jimmy Iovine and Dr. Dre, Eminem would go on to achieve mainstream success with The Slim Shady LP in 1999, which was certified 5x platinum.[56][57] Credited with popularizing hip hop in middle America, Eminem is critically acclaimed as one of the greatest rappers of all time.[49] Eminem's global success and acclaimed works are widely regarded as having broken racial barriers for the acceptance of white rappers in popular music, as well as helping launch the nationally successful careers of other Detroit rappers, including Hush, Proof, Obie Trice and Trick Trick, and forming the groups D12, and Bad Meets Evil, the latter of which featured fellow Detroit rapper Royce da 5'9".[50][58]

Rapper, DJ and breakdancer Kid Rock was a member of the Beast Crew in the 1980s, alongside Champtown and the Blackman, before signing a solo record contract with Jive Records at the age of 17, releasing his debut album Grits Sandwiches for Breakfast in 1990. The label subsequently dropped Kid Rock, fearing that the backlash against white rapper Vanilla Ice would hurt Kid Rock's sales,[59] and subsequently in 1993, a college radio station was fined $23,750 for playing Kid Rock's vulgar song, "Yo-Da-Lin In the Valley," the highest penalty leveled against a college radio station by the FCC up until that point. Undeterred by these controversies, Kid Rock continued to record independently. Although his debut album featured a hip-hop sound, the rapper became known locally in Detroit for his rap rock sound, which he developed with his backing band, Twisted Brown Trucker. After developing a strong local following in Detroit, Kid Rock signed with Atlantic Records and released his most successful album, Devil Without a Cause in 1998, which was certified diamond.[50][60] Kid Rock also helped launch the careers of Detroit hip-hop artists Joe C., Uncle Kracker and Paradime.[50] Additionally, Devil Without a Cause featured the national debut of Eminem, who delivered a guest verse on Kid Rock's song "Fuck Off" in exchange for Kid Rock scratching on Eminem's song "My Fault" on The Slim Shady LP, which was released the following year.[59]

Further developments (1996 onward)

The late 1990s saw the launch of Detroit's booty bass scene, a sound that was popular at Belle Isle Park parties, with artists DJ Assault, DJ Godfather and Disco D, and fusions of hip-hop and techno with artists like Anthony "Shake" Shakir, Robert Hood, Daniel Bell, Claude Young, Kenny Larkin, Eddie "Flashin'" Fowlkes, and Stacey Pullen.[50] After the Hip Hop Shop first closed in 1997, Lush Lounge became the new launching pad for aspiring hip-hop emcees, until the mid-2000s, when it closed down, although it was briefly reopened in 2008.[52] The following year, the sportswear store Bob's Classic Kicks began hosting the Air Up There Hip-Hop Showcase for developing hip-hop talents in its first 40 events, after which it has continued once a year at several other venues.[52]

Detroit hip-hop producer J Dilla developed his beat making skills as a member of the groups 1st Down and Slum Village, before embarking on a solo career in 2002; Dilla's music raised the artistic level of hip-hop production in Detroit, before his death in 2006. Dilla would subsequently become a major source of inspiration for future Detroit hip-hop artists, including Guilty Simpson and Elzhi.[50] The 2010s saw the rise of Detroit's underground hip-hop scene with artists such as Danny Brown, and the Crown Nation collective's Quelle Chris and Denmark Vessey, and Nick Speed.[2][50][61]

Venues

The city is home to the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and the Detroit Opera House. Major theaters include the Fox Theatre, Masonic Temple Theatre,[62] Fisher Theatre, The Fillmore Detroit, Music Hall Center for the Performing Arts, St. Andrews Hall, The Shelter, The Majestic Theatre, The Old Miami, The Magic Stick, The Lager House,[63] Detroit Repertory Theatre and the Detroit Film Theatre at the Detroit Institute of Arts,[64] along with Wayne State University's Hillberry, Bonstelle, and Studio Theatres.[64]

The metropolitan Detroit area boasts two of the top live music venues in the U.S. DTE Energy Music Theater (formerly Pine Knob) was the most attended summer venue in the U.S. in 2005 for the fifteenth consecutive year, while The Palace of Auburn Hills ranked twelfth, according to music industry source Pollstar.[65]

Suburban Detroit is also home to a handful of live music venues, including Clutch Cargo's (Pontiac), The Magic Bag (Ferndale),[66] The Crofoot (Pontiac),[62] The Historic Eagle Theater (Pontiac), The Blind Pig (Ann Arbor) The Ritz (Roseville MI 1980–1995, Warren MI 2006–present), Smalls (Hamtramck), High Octane—formerly Static Age (Romeo), Royal Oak Music Theatre (Royal Oak), NTP Backstage (Waterford).[67]

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

At least 25 groups or solo artists, non-performers and sidemen who are connected with the Detroit area have been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, including Detroit-native Bill Haley, Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson, Jackie Wilson, the Supremes, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Hank Ballard, the Four Tops, Gladys Knight & The Pips, John Lee Hooker, Alice Cooper, Wilson Pickett, Martha and the Vandellas, Little Willie John, Parliament-Funkadelic, James Jamerson, Holland-Dozier-Holland, Bob Seger, Glenn Frey, The Stooges, Berry Gordy, Patti Smith and Eminem.[68][69]

Symphony

See also

References

- "How Detroit Is Monetizing Techno". Forbes.com. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- Gavrilovich, Peter & Bill McGraw (2000). The Detroit Almanac. Detroit Free Press. ISBN 0-937247-34-0.

- Gavrilovich, Peter & Bill McGraw (2006). The Detroit Almanac, 2nd edition. Detroit Free Press. ISBN 978-0-937247-48-8.

- Jesaro, May (September 11, 2014). "Eminem's 'Rap God' Breaks Guinness World Record; Has 'Most Words in a Hit Record' With Roughly 4 Words Per Second". The Standard. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Paul Grein (December 11, 2013). "A Britney Spears Bummer: New Album Fizzles". Yahoo Music.

- Baulch, Vivian M. (September 4, 1999). Michigan's greatest treasure – Its people Archived July 31, 2007, at archive.today. Michigan History, The Detroit News. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- "Paradise Valley | Detroit Historical Society". Detroithistorical.org. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- Vivian Baulch (August 7, 1996).Paradise Valley and Black Bottom Archived February 15, 2013, at archive.today.Detroit News, Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- "HOME". Theofficialbakerskeyboardlounge.com.

- Dan Austin. "Grande Ballroom | Historic Detroit". Historicdetroit.org.

- Bjorn, Lars (2001). Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit 1920-60. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06765-6.

- "John Lee Hooker". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- Komara, Edward (2005). Encyclopedia of the Blues. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92699-8.

- "The Westwood Music Group". westwoodmusicgroup.com. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- "Joe von Battle - Requiem for A Record Shop Man". marshamusic.wordpress.com. November 8, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- "Farewell To A Detroit Blues Great". metrotimes.com. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- "The White Stripes Bio". AllMusic. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- "The White Stripes Sputnik". Sputnik Music. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- Leahey, Andrew. "The White Stripes". AllMusic. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- Lisa Collins (January 10, 2004). "Legacy Plays Role In New Sets". Billboard.com. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- Jazz Improv 2007, Volume 7, Issues 1–2, p. 209: "The Hot Club of Detroit was founded four years ago at Wayne State University and since that time has gone on to take first place in the 2004 Detroit International Jazz Festival competition and win the 2006 Detroit Music Award for Outstanding ..."

- Hirshey, Gerri (1994). Nowhere to Run: The Story of Soul Music. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80581-2.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 5, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Motownmansion.com". Motownmansion.com. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Carson, David A. (2005). Noise, and Revolution: The Birth of Detroit Rock 'n' Roll. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11503-0.

- Harrington, Joe (2002). Sonic Cool: The Life and Death of Rock'N'Roll. Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-634-02861-8., p. 251.

- Bogdanov, Vladimir and Chris Woodstra, Stephen Thomas Erlewine, John Bush (2002). All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (3rd Ed.). Hal Leonard: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-653-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The Stooges Set the Stage for Punk 50 Years Ago". The Saturday Evening Post. August 9, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- Milo, Jeff (September 30, 2018). "MC5 - 50 Years Later: Local Musicians Chime In On Lasting Influence". ecurrent.com. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- Callwood, B. (2010). Mc5 : Sonically speaking. Wayne State University Press. p. 129.

- McNeil, Legs (2006). Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-4264-8.

- Pevos, Edward (March 4, 2020). "30 famous singers and bands you may not know are from Michigan". MLive.

- Rettman, Tony (2008). "Michigan hardcore pioneers Violent Apathy reunite for shows". Swindle (issue 12). Archived from the original on October 25, 2007.

- Nelson, Jason."Degenerates (Online Band Profile / Biography)". stereokiller.com (website).

- Sauter, Cale (June 20, 2007). "Michigan hardcore pioneers Violent Apathy reunite for shows". City Pulse.

- Nelson, Jason. "Spite (Online Band Profile & Biography)". stereokiller.com (website).

- "KFTH - Negative Approach Interview from Game of the Arseholes #4". Homepages.nyu.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- "Touch and Go / Quarterstick Records". Touchandgorecords.com. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Jackman, Michael. "Before punk broke". Detroit Metro Times. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- "FORCED ANGER | Free Music, Mixes, Tour Dates, Photos, Videos". Myspace.com. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Squirrel & Gabby. "A Tribute to the Detroit Punk Rock Scene 1977-1990". detroitpunk.net (website).

- Edwards, Jessica. "High Tech Soul". Plexifilm. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Woodford, Arthur M. (2001). This is Detroit 1701–2001. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2914-4.

- "Techno music pulses in Detroit". CNN. February 13, 2003. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- "A Brief History of Techno". Gridface. October 17, 1999. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Shapiro, Peter (2000). Modulations: A History of Electronic Music, Throbbing Words on Sound. Caipirinha Productions. pp. 108–121. ISBN 1-891024-06-X.

- "Raymond Scott's Manhattan Research". February 21, 2006. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- "Best Rappers List | Greatest of All Time". Billboard. November 12, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Rubin, Mike (October 10, 2013). "The 411 On The 313: A Brief History of Detroit Hip-Hop". Complex. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- Santori Davison, Kahn (March 9, 2016). "An instant lesson in the history of Detroit hip-hop". Metro Times. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- Santori Davison, Kahn (March 15, 2018). "Remembering notable locales among Detroit's hip-hop history". Metro Times. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- McCollum, Brian (November 8, 2002). "Film exaggerates the support early hip-hop had in Detroit.". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- Bruce, Joseph; Hobey Echlin (August 2003). "Paying Dues". In Nathan Fostey (ed.). ICP: Behind the Paint (second ed.). Royal Oak, Michigan: Psychopathic Records. pp. 164–167. ISBN 0-9741846-0-8.

- "Before Eminem, there was Esham". Chicago Tribune. December 9, 2003. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- "Eight Eminem Albums Charted On Billboard 200 This Week". XXL. Harris Publications. Archived from the original on June 12, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- David, Barry (February 8, 2003). "Shania, Backstreet, Britney, Eminem and Janet Top All Time Sellers". Music Industry News Network. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

- Icons of hip hop : an encyclopedia of the movement, music, and culture. Internet Archive. Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-313-33902-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - McCollum, Brian (August 6, 2015). "Kid Rock before the fame: The definitive Detroit oral history". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- Unterberger, Andrew (September 29, 2016). "All 92 Diamond-Certified Albums Ranked From Worst to Best: Critic's Take". www.billboard.com. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Bogdanov, Vladimir and Chris Woodstra, Stephen Thomas Erlewine, John Bush (2003). All Music Guide to Hip-Hop: The Definitive Guide to Rap and Hip-Hop. Hal Leonard: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-759-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Live in the D: Masonic Temple, The Crofoot team up for concerts | News - Home". Clickondetroit.com. September 24, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- "10 Note-Worthy Detroit Music Venues". Pure Michigan.

- Hauser, Michael & Marianne Weldon (2006). Downtown Detroit's Movie Palaces (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-4102-8.

- "DTE Energy Music Theatre Listed as 2004 Top Attended Amphitheatre". Palacenet.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2005. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- "Home - The Magic Bag - Detroit's Premier Nightlife, Concert & Comedy Venue". The Magic Bag. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- "NTP Backstage". Ntpbackstage.tumblr.com. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- "Inductees A to Z". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- Dresdale, Andrea; Tuccillo, Andrea (November 7, 2022). "Dolly Parton, Eminem, Lionel Richie and more inducted into Rock & Roll Hall of Fame". ABC News. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

Further reading

- Bogdanov, Vladimir and Chris Woodstra, Stephen Thomas Erlewine, John Bush (2003). All Music Guide to Hip-Hop: The Definitive Guide to Rap and Hip-Hop. Hal Leonard: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-759-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bogdanov, Vladimir and Chris Woodstra, Stephen Thomas Erlewine, John Bush (2002). All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (3rd Ed.). Hal Leonard: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-653-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bjorn, Lars with Jim Gallert (2001). Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit 1920-1960. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06765-6.

- Boland, S.R. & Marilyn Bond (2002). The Birth of the Detroit Sound: 1940-1964. Arcadia. ISBN 0-7385-2033-0.

- Gavrilovich, Peter & Bill McGraw (2000). The Detroit Almanac. Detroit Free Press. ISBN 0-937247-34-0.

- Harrington, Joe (2002). Sonic Cool: The Life and Death of Rock'N'Roll. Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-634-02861-8.

- Heiles, Ann Mischakoff (2007). America's Concertmasters (Detroit Monographs in Musicology). Harmonie Park. ISBN 978-0-89990-139-8.

- Schmitt, Jason M. (2008). Like the Last 30 Years Never Happened: Understanding Detroit Rock Music Through Oral History. OCLC 655118703.

- Taylor, Harold Keith (2004). The Motown Music Machine. Jadmeg Music. ISBN 0-9741196-2-8.

- Woodford, Arthur M. (2001). This is Detroit 1701–2001. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2914-4.

.svg.png.webp)