German South West Africa

German South West Africa (German: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884[1] until 1915,[2] though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

German South West Africa Deutsch-Südwestafrika | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884–1915 | |||||||||||||||

Service flag of the Colonial Office

Coat of arms of the German Empire

| |||||||||||||||

Green: German South West Africa Dark gray: Other German colonial possessions Darkest gray: German Empire (1911 borders) | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Colony of Germany | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Windhuk (from 1891) | ||||||||||||||

| Official languages | German | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity Indigenous beliefs | ||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||

• 1894–1905 | Theodor von Leutwein | ||||||||||||||

• 1905–1907 | Friedrich von Lindequist | ||||||||||||||

• 1907–1910 | Bruno von Schuckmann | ||||||||||||||

• 1910–1919 | Theodor Seitz | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Scramble for Africa | ||||||||||||||

• Start of colonial occupation by the German Empire | 7 August 1884 | ||||||||||||||

| 1904–1908 | |||||||||||||||

| 9 July 1915 | |||||||||||||||

| 28 June 1919 | |||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1912 | 835,100 km2 (322,400 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1912 | 250,000 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | German South West African Mark | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Namibia | ||||||||||||||

German rule over this territory was punctuated by numerous rebellions by its native African peoples, which culminated in a campaign of German reprisals from 1904 to 1908 known as the Herero and Namaqua genocide.

In 1915, during World War I, German South West Africa was invaded by the Western Allies in the form of South African and British forces. After the war its administration was taken over by the Union of South Africa (part of the British Empire) and the territory was administered as South West Africa under a League of Nations mandate. It became independent as Namibia on 21 March 1990.

Early settlements

Initial European contact with the areas which would become German South West Africa came from traders and sailors, starting in January 1486 when Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão, possibly accompanied by Martin Behaim, landed at Cape Cross. However, for several centuries, European settlement would remain limited and temporary. In February 1805, the London Missionary Society established a small mission in Blydeverwacht, but the efforts of this group met with little success. In 1840, the London Missionary Society transferred all of its activities to the German Rhenish Missionary Society. Some of the first representatives of this organisation were Franz Heinrich Kleinschmidt (who arrived in October 1842) and Carl Hugo Hahn (who arrived in December 1842). They began founding churches throughout the territory. The Rhenish missionaries had a significant impact initially on culture and dress, and then later on politics. During the same time that the Rhenish missionaries were active, merchants and farmers were establishing outposts.

Early history

On 16 November 1882, a German merchant from Bremen, Adolf Lüderitz, requested protection for a station that he planned to build in South West Africa, from Chancellor Bismarck. Once this was granted, his employee, Heinrich Vogelsang, purchased land from a native chief and established a settlement at Angra Pequena which was renamed Lüderitz.[1] On 24 April 1884, he placed the area under the protection of Imperial Germany to deter possible encroachment by other European powers. In early 1884, the gunboat SMS Nautilus visited to review the situation. A favourable report from the government, and acquiescence from the British, resulted in a visit from the corvettes Leipzig and Elisabeth. The German flag was finally raised in South West Africa on 7 August 1884. The German claims on this land were confirmed during the Conference of Berlin. In October, the newly appointed Commissioner for West Africa, Gustav Nachtigal, arrived on the Möwe.[3]

In April 1885, the Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft für Südwest-Afrika (German Colonial Society for Southwest Africa, known as DKGSWA) was founded with the support of German bankers (Gerson von Bleichröder, Adolph von Hansemann), industrialists (Count Guido Henckel von Donnersmarck) and politicians (Frankfurt mayor Johannes von Miquel).[4] DKGSWA was granted monopoly rights to exploit mineral deposits, following Bismarck's policy that private rather than public money should be used to develop the colonies.[5] The new Society soon bought the assets of Lüderitz's failing enterprises, land and mineral rights.[4] Lüderitz drowned the next year while on an expedition to the mouth of the Orange River.[1] Later, in 1908, diamonds were discovered. Thus along with gold, copper, platinum, and other minerals, diamonds became a major investment.[5]

In May, Heinrich Ernst Göring was appointed Commissioner and established his administration at Otjimbingwe. Then, on 17 April 1886, a law creating the legal system of the colony was passed, creating a dual system with laws for Europeans and different laws for natives.[6]

Over the following years, relations between the German settlers and the indigenous peoples continued to worsen. Additionally, the British settlement at Walvis Bay, a coastal enclave within South West Africa, continued to develop, and many small farmers and missionaries moved into the region. A complex web of treaties, agreements, and vendettas increased the unrest. In 1888 the first group of Schutztruppen—colonial protectorate troops—arrived, sent to protect the military base at Otjimbingwe.

In 1890, the colony was declared a German Crown Colony, and more troops were sent.[7] In July of the same year, as part of the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty between Britain and Germany, the colony grew in size through the acquisition of the Caprivi Strip in the northeast, promising new trade routes into the interior.[8]

Almost simultaneously, between August and September 1892, the South West Africa Company Ltd (SWAC) was established by the German, British, and Cape Colony governments, aided by financiers to raise the capital required to enlarge mineral exploitation (specifically, the Damaraland concession's copper deposit interests).

A veterinary cordon fence was introduced in 1896 to control rinderpest by restricting population and livestock movement. Later known as the Red Line, it became a political boundary with police protection concentrated south of the line, while northern areas were controlled though indirect colonial rule using traditional authorities. This led to different political and economic outcomes for example between the northern Ovambo people compared to the more centrally located Herero people.[9]

German South West Africa was the only German colony in which Germans settled in large numbers. German settlers were drawn to the colony by economic possibilities in diamond and copper mining, and especially farming. In 1902 the colony had 200,000 inhabitants, although only 2,595 (1.2%) were recorded as German, while 1,354 (0.6%) were Afrikaners and 452 (0.2%) were British. By 1914, 9,000 more German settlers had arrived. There were probably around 80,000 Herero, 60,000 Ovambo, and 10,000 Nama, who were referred to as Hottentots.

Rebellion against German rule and genocide of the Herero and Namaqua

Through 1893 and 1894, the first "Hottentot Uprising" of the Nama and their leader Hendrik Witbooi occurred. The following years saw many further local uprisings against German rule. Before the Herero and Namaqua genocide of 1904–1907, the Herero and Nama had good reasons to distrust the Germans, culminating in the Khaua-Mbandjeru rebellion. This rebellion, in which the Germans tried to control the Khaua by seizing their property under cover of European legal views of property ownership (criticised at home for being no real reform of the notion of collective tribal ownership). This led to the largest of the rebellions, known as the Herero Wars (or Herero genocide) of 1904.

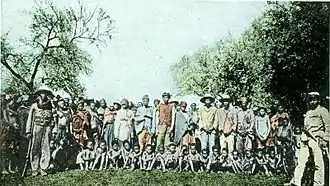

Remote farms were attacked, and approximately 150 German settlers were killed. The Schutztruppe of only 766 troops and native auxiliary forces was, at first, no match for the Herero. The Herero went on the offensive, sometimes surrounding Okahandja and Windhoek, and destroying the railway bridge to Osona. Additional 14,000 troops, hastened from Germany under Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha, crushed the rebellion in the Battle of Waterberg.

Earlier von Trotha issued an ultimatum to the Herero people, denying them the right of being German subjects and ordering them to leave the country or be killed. To escape, the Herero retreated into the waterless Omaheke region, a western arm of the Kalahari Desert, where many of them died of thirst. The German forces guarded every water source and were given orders to shoot any adult male Herero on sight. Only a few Herero managed to escape into neighbouring British Bechuanaland.[10]

The German official military report on the campaign lauded the tactics:

This bold enterprise shows up in the most brilliant light the ruthless energy of the German command in pursuing their beaten enemy. No pains, no sacrifices were spared in eliminating the last remnants of enemy resistance. Like a wounded beast the enemy was tracked down from one water-hole to the next until finally, he became the victim of his own environment. The arid Omaheke [desert] was to complete what the German army had begun: the extermination of the Herero nation.

— Bley, 1971: 162

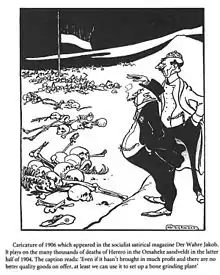

In late 1904, the Nama entered the struggles against the colonial power under their leaders Hendrik Witbooi and Jakobus Morenga, the latter often referred to as "the black Napoleon", despite losing most of his battles. This uprising was finally quashed during 1907–1908. In total, between 25,000 and 100,000 Herero, more than 10,000 Nama and 1,749 Germans died in the conflict.

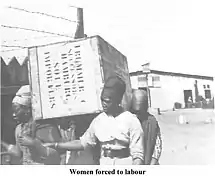

After the official end of the conflict, the remaining natives, when finally released from detention, were subject to a policy of dispossession, deportation, forced labour, and racial segregation and discrimination in a system that in many ways anticipated apartheid. The genocide remains relevant to ethnic identity in independent Namibia and to relations with Germany.[11]

The neighbouring British objected to what they regarded as the inhumane German policy. This involved maintaining a number of concentration camps in the colony during their war against the Herero and Nama peoples. Besides these camps, the indigenous people were interned in other places. These included private businesses and government projects,[12] ships offshore,[13][14][15] Etappenkommando in charge of supplies of prisoners to companies, private persons, etc., as well as any other materials. Concentration camps implies poor sanitation and a population density that would imply disease.[16] Prisoners were used as slave labourers in mines and railways, for use by the military or settlers.[17][18][19]

The Herero and Namaqua genocide has been recognised by the United Nations and by the Federal Republic of Germany.[20] On the 100th anniversary of the camp's foundation, German Minister for Economic Development and Cooperation Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul commemorated the dead on-site and apologised for the camp on behalf of Germany.[21][22] In May 2021, after five years of negotiations, the German government - recognising the Hottentot Rebellion as a colonial genocide - set up a $1.3 billion compensation fund.[23]

Gallery

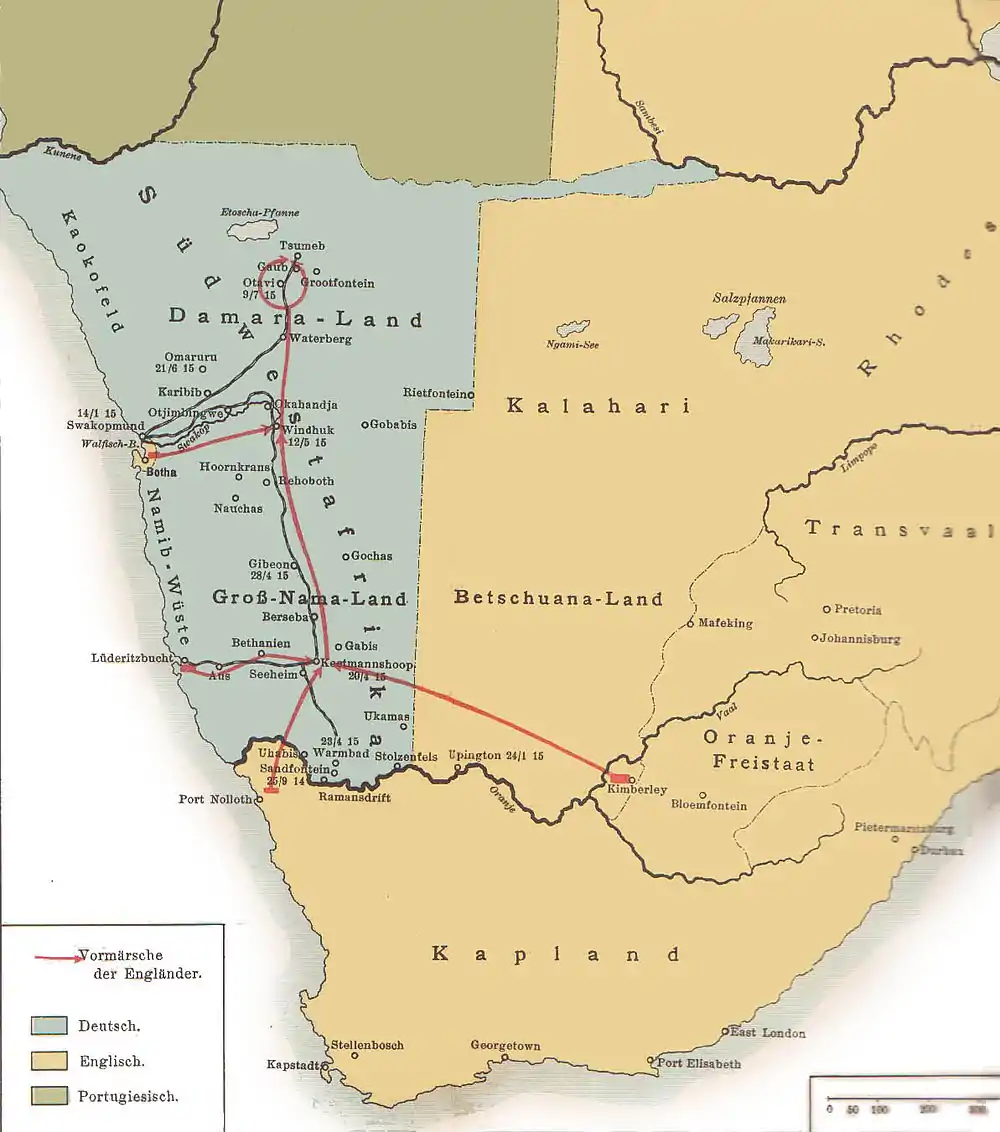

First World War

The news about the start of World War I reached German South West Africa on 2 August 1914 via radio telegraphy. The information was transmitted from the Nauen transmitter station via a relay station in Kamina and Lomé in Togoland to the radio station in Windhoek.

After the start of the war, South African troops opened hostilities with an assault on the Ramansdrift police station on 13 September 1914. German settlers were transported to concentration camps near Pretoria and later in Pietermaritzburg. Because of the overwhelming numerical superiority of the South African troops, the German Schutztruppe, along with groups of Afrikaner volunteers fighting in the Maritz rebellion on the German side, offered opposition only as a delaying tactic. On 9 July 1915, Victor Franke, the last commander of the Schutztruppe, capitulated near Khorab.

Two members of the Schutztruppe, geography professors Fritz Jaeger and Leo Waibel, are remembered for their explorations of the northern part of German South West Africa, which became the book Contributions to the Geography of South West Africa (Beiträge zur Landeskunde von Südwestafrika).[24]

Postwar

After the war, the territory came under the control of Britain which was then formalized through a South African League of Nations mandate which made Union of South Africa responsible for administration.[25] The territory eventually became subject to apartheid under South African rule, as well as becoming involved in the Angolan civil war in 1975.[26] In 1990, the former colony became independent as Namibia, governed by the former liberation movement SWAPO.

German legacy

Many German names, buildings, and businesses still exist in the country, and about 30,000 people of German descent still live there. German is still widely used in Namibia, with the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation operating a German-language radio station and broadcasting television news bulletins in German, while the daily newspaper Allgemeine Zeitung, founded in 1916, remains in publication.[27] Deukom, a satellite television service, offers television and radio channels from Germany.[28]

In addition, Lutheranism is the predominant Christian denomination in present-day Namibia.

German placenames

Most place names in German South West Africa continued to bear German spellings of the local names, as well as German translations of some local phrases. The few exceptions to the rule included places founded by the Rhenish Missionary Society, generally biblical names, as well as:

- Hoornkrans

- Sandfontein

- Stolzenfels

- Waterberg (Otjiwarongo)

Planned symbols for German South West Africa

In 1914 a series of drafts were made for proposed Coat of Arms and Flags for the German Colonies. However, World War I broke out before the designs were finished and implemented and the symbols were never actually taken into use. Following the defeat in the war, Germany lost all its colonies and the prepared coat of arms and flags were therefore never used.

Proposed flag

Proposed flag Proposed coat of arms

Proposed coat of arms

See also

References

- Notes

- Hammer, Joshua (13 June 2008). "Retracing the steps of German colonizers in Namibia". The New York Times.

- "German South West Africa". Away from the Western Front. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- Dierks 2002, p. 38 Chapter 4.1 Initial Period of German South West Africa (SWA): 1884-1889 Chronology 1884 Section

- "Deutsches Koloniallexikon 1920, SCHNEE, H.(Buchstabe: Deutsche_Kolonialgesellschaft_fuer_Suedwestafrika)". www.ub.bildarchiv-dkg.uni-frankfurt.de.

- "39-1885". www.klausdierks.com.

- "40-1886". www.klausdierks.com.

- "45-1890". www.klausdierks.com.

- Heawood, Edward; and several others (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 01 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 320–358, see page 343.

Germany's share of South Africa......in July 1890, the British and German governments came to an agreement as to the limits of their respective spheres of influence in various parts of Africa, the boundaries of German South-West Africa were fixed in their present position.

- Indirect Colonial Rule Undermines Support for Democracy: Evidence From a Natural Experiment in Namibia, Marie Lechler and Lachlan McNamee, Comparative Political Studies 2018, Vol. 51(14) 1858–1898

- "Michael Mann – German South West Africa: The Genocide of the Hereros, 1904-5". Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- Reinhart Kössler, and Henning Melber, "Völkermord und Gedenken: Der Genozid an den Herero und Nama in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1904–1908," ("Genocide and memory: the genocide of the Herero and Nama in German South West Africa, 1904–08") Jahrbuch zur Geschichte und Wirkung des Holocaust 2004: 37–75

- Erichsen 2005, p. 49

- Erichsen 2005, p. 23

- Erichsen 2005, pp. 59, 111

- Erichsen 2005, p. 76

- Erichsen 2005, p. 113

- Erichsen 2005, p. 43

- "The loads … are out of all proportion to their strength. I have often seen women and children dropping down, especially when engaged on this work, and also when carrying very heavy bags of grain, weighing from 100 to 160lbs." Erichsen 2005, p. 58

- "Forcing women to pull carts as if they were animals was in tune with the treatment generally meted out to Herero prisoners in Lüderitz as elsewhere in the colony." Erichsen 2005, p. 84

- Zimmerer 2016, pp. 215–225

- "Germany admits Namibia genocide," BBC News, 14 August 2004

- "Namibia – Genocide and the second Reich". Netherlands: Mazalien (defunct). Archived from the original on 9 June 2007.

- "Germany officially recognizes colonial-era Namibia genocide". Deutsche Welle. 28 May 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- Jaeger, Fritz; Leo Waibel (1920–1921). "Contributions to the Geography of South West Africa". World Digital Library (in German). Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "South-West Africa". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- "Namibia - the Boer conquest | Britannica".

- Tools of the Regime: Namibian Radio History and Selective Sound Archiving 1979–2009 Archived 18 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Presented at the Sound Archives Workshop, Basel, 4 September 2009

- "Sender | Deukom". www.deukom.co.za.

- Bibliography

- Dierks, Klaus (2002). Chronology of Namibian History: From Pre-historical Times to Independent Namibia (second ed.). Windhoek: Namibia Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft/Namibia Scientific Society. ISBN 978-99916-40-10-5. Table of Contents

- Erichsen, Casper W. (2005). "The angel of death has descended violently among them": Concentration camps and prisoners-of-war in Namibia, 1904–1908. African Studies Centre, University of Leiden. ISBN 978-90-5448-064-8.

- Zimmerer, Jürgen; et al. (2016). Völkermord in Deutsch-Südwestafrika der Kolonialkrieg (1904-1908) in Namibia und seine Folgen [Genocide in German South West Africa, the colonial war (1904-1908) in Namibia and its consequences] (in German) (second ed.). Berlin: Christoph Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86153-898-1. Table of Contents

- Schnee, Heinrich, ed. (1920). Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon (in German). Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer. OCLC 560343661. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

Further reading

- Aydelotte, William Osgood. "The First German Colony and Its Diplomatic Consequences." Cambridge Historical Journal 5#3 (1937): 291-313. Online

- Bullock, A.L.C. Germany's Colonial Demands, Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). pp. 800–804.

- Hull, Isabel. Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006. Preview

- Hillebrecht, Werner. "'Certain uncertainties', or venturing progressively into colonial apologetics?" Journal of Namibian Studies, 1. 2007. pp. 73–95. Accessed 6 September 2020. Online

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 1, 2. Auflage, Windhoek 2012, ISBN 978-99916-872-1-6

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 2, "Naulila", Windhoek 2012, ISBN 978-99916-872-3-0

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 3, "Kämpfe im Süden", Windhoek 2014, ISBN 978-99916-872-8-5

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 4, "Der Süden ist verloren", Windhoek 2016, ISBN 978-99916-909-2-6

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 5, "Aufgabe der Küste", Windhoek 2016, ISBN 978-99916-909-4-0

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 6, "Aufgabe der Zentralregionen", Windhoek 2017, ISBN 978-99916-909-5-7

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 7, "Der Ring schließt sich", Windhoek 2018, ISBN 978-99916-909-7-1

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 8, "Das Ende bei Khorab", Windhoek 2018, ISBN 978-99916-909-9-5

- Krömer/Krömer: "Fotografische Erinnerungen an Deutsch-Südwestafrika", Band 1, Fotos und Ansichtskarten aus Kriegs- und Friedenstagen, Windhoek 2012, ISBN 978-99916-872-4-7

- Krömer/Krömer: "Fotografische Erinnerungen an Deutsch-Südwestafrika", Band 2, Orte, Menschen und Geschichte in alten Fotografien, Windhoek 2013, ISBN 978-99916-872-7-8

- Krömer/Krömer: "Fotografische Erinnerungen an Deutsch-Südwestafrika", Band 3, Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika, Windhoek 2018, ISBN 978-99916-909-8-8

- Reith, Wolfgang: "Die Oberhäuptlinge des Hererovolkes", Von den Anfängen bis zum ungelösten Streit der Gegenwart, Windhoek 2017, ISBN 978-99916-895-1-7

- Reith, Wolfgang: "Die Kaiserlichen Schutztruppen", Deutschlands Kolonialarmee 1889-1919, Windhoek 2017, ISBN 978-99916-909-6-4