Deutsche Reichsbahn

The Deutsche Reichsbahn, also known as the German National Railway,[1] the German State Railway, German Reich Railway,[2] and the German Imperial Railway,[3][4] was the German national railway system created after the end of World War I from the regional railways of the individual states of the German Empire. The Deutsche Reichsbahn has been described as "the largest enterprise in the capitalist world in the years between 1920 and 1932";[1] nevertheless its importance "arises primarily from the fact that the Reichsbahn was at the center of events in a period of great turmoil in German history".[1]

DR emblem during the Weimar Republic | |

| Industry | Rail transport |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | German state railways |

| Founded | 1 April 1920 |

| Defunct | 7 October 1949 |

| Successors | |

Area served |

|

Overview

The company was founded on 1 April 1920 as the Deutsche Reichseisenbahnen ("German Imperial Railways")[1] when the Weimar Republic, which still used the nation-state term of the previous monarchy, Deutsches Reich (German Reich, hence the usage of the Reich in the name of the railway; the monarchical term was Deutsches Kaiserreich), took national control of the German railways, which had previously been run by the German states (Länderbahnen). In 1924 it was reorganised under the aegis of the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft ("German Imperial Railway Company", DRG), a nominally private railway company, which was 100% owned by the German state. In 1937 the railway was reorganised again as a state authority and given the name Deutsche Reichsbahn ("German Imperial Railway", DRB). After the Anschluss in 1938 the DR also took over the Bundesbahn Österreich ("Federal Railway of Austria", BBÖ).[5][6][7][8]

The East and West German states were founded in 1949. East Germany took over the control of the DR on its territory and continued to use the traditional name Deutsche Reichsbahn, while the railway in West Germany became the Deutsche Bundesbahn ("German Federal Railway", DB). The Austrian Österreichische Bundesbahnen ("Austrian Federal Railways", ÖBB) was founded in 1945, and was given its present name in 1947.

In January 1994, following German reunification, the East German Deutsche Reichsbahn merged with the West German Deutsche Bundesbahn to form Germany's new national carrier, Deutsche Bahn AG ("German Rail", DBAG), technically no longer a government agency but still a 100% state-owned joint stock company.

History

Deutsche Reichseisenbahnen (1920–1924)

The first railways to be owned by the German Empire, which was founded in 1871, were the Imperial Railways in Alsace-Lorraine, whose Imperial General Division of Railways in Alsace-Lorraine (Kaiserliche General-Direktion der Eisenbahnen in Elsass-Lothringen) had its headquarters in Straßburg (now Strasbourg). It was formed after France had ceded the territory of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871 to the German Empire and the newly created Third French Republic had formally purchased the French Eastern Railway Company (French: Compagnie des chemins de fer de l'Est or German: Französische Ostbahn-Gesellschaft) and then sold it again to the German Empire. After the end of the First World War this national "imperial railway" was taken back by France.

In the remaining German states, by contrast, the existing state railways continued to be subject to their respective sovereigns, despite the fact that Otto von Bismarck had tried in vain to purchase the main railway lines for the Empire. A similar attempt failed in 1875 as a result of opposition from the middle powers when Albert von Maybach presented a draft Reich Railway Act to the Bundesrat.

In the wake of the stipulations of the Weimar Constitution of 11 August 1919, the state treaty on the foundation of the Deutsche Reichseisenbahnen ("German Reich Railways") came into force on 1 April 1920. This resulted in the merger of the existing state railways (Länderbahnen) of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Württemberg, Baden, Mecklenburg and Oldenburg under the newly formed German Reich. The state railways that merged were the:

- Baden state railways

- Mecklenburg state railways

- Oldenburg state railways

- Bavarian state railways

- Saxon state railways

- Württemberg state railways

- Prussian-Hessian state railways

Initially called the Reichseisenbahnen or Deutsche Reichseisenbahnen, the Reich Minister of Transport, Wilhelm Groener, formerly gave them the name "Deutsche Reichsbahn" in his decree of 27 June 1921. In 1922 the old railway divisions (Eisenbahndirektionen) were renamed as Reich railway divisions (Reichsbahndirektionen).[9]

Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft (1924–1937)

Among the provisions of the 1924 Dawes Plan was a plan to utilize the state railway completely for the payment of war reparations. Following the plan's publication, on 12 February 1924, the Reich government announced the creation of the Deutsche Reichsbahn as a state enterprise under the Reich Ministry of Transport (German: Reichsverkehrsministerium).

As this was not enough to satisfy the reparations creditors, on 30 August 1924 a law was enacted providing for the establishment of a state-owned Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft ("German Imperial Railway Company", DRG) as a public holding company to operate the national railways. The aim was to earn profits which, under the Dawes Plan, were to be used to contribute to Germany's war reparations.

At the same time as the Reichsbahn law was enacted, the company was handed a bill of eleven billion Goldmarks to be paid to the Allied powers, while its original capital was valued at fifteen billion Goldmarks. These terms were later amended in the Young Plan. Nevertheless, the Great Depression and the regular payment of war reparations (about 660 million Reichsmarks annually) put a considerable strain on the Reichsbahn. Not until the Lausanne Conference of 1932 was the Reichsbahn released from its financial obligations. In total, about 3.87 billion Goldmarks was paid in reparations to the Allied powers.

During the DRG period the following milestones occurred:

- 1 October 1930: the DRG took over the Bremen Port Railway (Hafenbahn Bremen)

- 27 June 1933: the DRG's sister company the Reichsautobahn was founded

- 1 March 1935: the railways of the Saar were incorporated

The beginning of the DRG was characterised by the acquisition of new rolling stock built to standard types, such as the standard steam locomotives (Einheitsdampflokomotiven). The stock already in use had been inherited from the various state railways and comprised a great number of designs, many of them quite old. In fact, the DRG was unable to procure new stock in the numbers it wanted to both for financial reasons and due to delays in upgrading the lines to carry higher axle loads. The locomotive classes taken over from the old state railways, especially those from the Prussia, continued to dominate the scene until the end of the 1930s. They included, for example, the Prussian P 8 (BR 38.10-40), Prussian P 10 (BR 39), Prussian G 12 (BR 58.10) and the Prussian T 20 (BR 95). The Bavarian S 3/6 (BR 18.5) express locomotive even continued in production until 1930.

Not until the procurement programme for the wartime Kriegslokomotiven were new goods locomotives built in large numbers, but of course now for a very different purpose.

Taking lead from the German Labor Front, the Deutsche Reichsbahn took part in the conflict of intermarriage in Germany. In August 1933 Robert Ley, leader of Reich Labor, demanded that those administrators working for the German Labor Front be married only to German individuals. The Deutsche Reichsbahn took the lead in discriminating against intermarried workers, firing German employees married to Jews and forbidding intermarried Germans from working there in the future, starting in November 1933.[10]

In 1935 the railway network had a total of 68,728 kilometres (42,706 mi) of line, of which 30,330 km (18,850 mi) was main line railway, 27,209 km (16,907 mi) were branch lines and 10,496 km (6,522 mi) were light railways.[11]

In the latter part of the 1930s, the development of high-speed trains like the "Flying Hamburger" was accelerated. Before that streamlined steam engines had been built, but they were not as economical as the high-speed diesel and electric railcars. Although the Borsig streamlined steam engine, the no. 05 002 reached a speed of 200.4 km/h (124.5 mph) during a demonstration run, the Reichsbahn preferred fast railcars on its high speed network. The potential of these express trains was demonstrated by the Schienenzeppelin in its record run on 21 June 1931 when it reached a top speed of 230.2 km/h (143.0 mph).

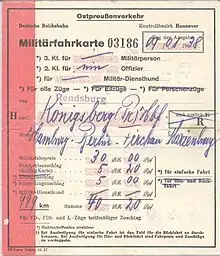

Before the Second World War the most important railway lines ran in an east–west direction. The high-speed lines at that time were on the Prussian Eastern Railway which ran through the Polish corridor (albeit slower there due to the poor state of the tracks), the lines from Berlin to Hamburg, via Hanover to the Ruhrgebiet, via Frankfurt am Main to southwest Germany, on which the diesel express trains ran, and the Silesian Railway from Berlin to Breslau (now Wrocław).

Bavarian Group Administration

Within the state of Bavaria, the Bavarian Group Administration (Gruppenverwaltung Bayern) had its head office (Zentrales Maschinen- und Bauamt) and was largely independent by § III 14 of the DRG's company regulations. It was responsible for the electrification of many lines, following the commencement of electric power generation to the railways at the Walchensee Power Plant, and for the independent trialling and procurement of locomotives and passenger coaches. The Group Administration introduced, for example, the Class E 32 locomotive and Class ET 85 railcar into service.

Bavaria also continued to use its own signalling system for many years after the merger.

In 1933 the Group Administration was disbanded and administration of the railways in Bavaria was taken over by the Deutsche Reichsbahn.

Leadership of the Reichsbahn

At the head of the Reichsbahn was a director general (Generaldirektor). The office holders were:

- 1924–1926 Rudolf Oeser

- 1926–1945 Julius Dorpmüller

From 1925, the director general had a permanent deputy. These were:

- 1925–1926 Julius Dorpmüller

- 1926–1933 Wilhelm Weirauch

- 1933–1942 Wilhelm Kleinmann

- 1942–1945 Albert Ganzenmüller

As a result of the Reichsbahn Act of 11 July 1939, the Reich Transport Minister became the director general of the Reichsbahn by his office. Dorpmüller, who since 1937 was also in charge of the Reich Ministry of Transport, continued in office as the director general after 1939 under this new legal framework.

Deutsche Reichsbahn (1937–1945)

With the Act for the New Regulation of the Conditions of the Reichsbank and the Deutsche Reichsbahn (Gesetz zur Neuregelung der Verhältnisse der Reichsbank und der Deutschen Reichsbahn) of 10 February 1937 the Deutsche Reichsbahn Gesellschaft was placed under Reich sovereignty and was given the name Deutsche Reichsbahn.

World War II and military use

The Reichsbahn had an important logistic role in supporting the rapid movement of the troops of the Wehrmacht, for example:

- March 1938: the annexation of Austria (Anschluss) and

- October 1938: the annexation of the Sudetenland after the Munich Agreement

- March 1939: the German occupation of Czechoslovakia

- September/October 1939: the invasion of Poland

- April 1940: Operation Weserübung (the invasions of Denmark and Norway)

- May/June 1940: the Battle of France

- 1941: Operation Barbarossa and the Balkan Campaign.

In all the occupied lands the Reichsbahn endeavoured to incorporate the captured railways (rolling stock and infrastructure) into their system. Even towards the end of the war the Reichsbahn continued to move military formations. For example, in the last great offensive, the Battle of the Bulge (from 16 December 1944), tank formations were transported from Hungary to the Ardennes.

The railways managed by the "Eastern Railway Division" (Generaldirektion der Ostbahn) were initially run from that part of the Polish State Railways within the so-called General Government-assigned part of the Polnischen Staatsbahnen (PKP), but from November 1939 by the Ostbahn (Generalgouvernement).

_Lantern_c1942.jpg.webp)

In the campaigns against Poland, Denmark, France, Yugoslavia, Greece etc. the newly acquired standard gauge networks could be used without difficulty. By contrast, after the start of the invasion of Russia on 22 June 1941, the problem arose of transferring troops and materiel to Soviet broad gauge lines or converting them to German standard gauge. Confounding German plans, the Red Army and Soviet railways managed to withdraw or destroy the majority of its rolling stock during its retreat. As a result, German standard gauge rolling stock had to be used for an additional logistic role within Russia; this required the laying of standard gauge track. The price was high: Reichsbahn railway staff and the railway troops of the Wehrmacht had to convert a total of 16,148 kilometres (10,034 mi) of Soviet trackage to German standard gauge track between 22 June and 8 October 1941.[12]

During the war, locomotives in the war zones were sometimes given camouflage livery. In addition, locomotives were painted with the Hoheitsadler symbol (the eagle, Germany's traditional symbol of national sovereignty) holding a swastika. On goods wagons the name "Deutsche Reichsbahn" was replaced by the letters "DR". Postal coaches continued to bear the name "Deutsche Reichspost".

The logistics of the Reichsbahn were crucial to the conduct of Germany's military offensives. The preparations for the invasion of Russia saw the greatest troop deployment by rail in history.

Expansion

Characteristic of the first six and a half years of this period was the exponential growth of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, which was almost exclusively due to the takeover of other national railways. This affected both parts of foreign state railways (in Austria the entire state railway) in the countries annexed by the Deutsche Reich, as well as private railways in Germany and in other countries:

| Date of takeover | Name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 18 March 1938 | Austrian Federal Railways (BBÖ) | The takeover of rolling stock officially followed on 1 January 1939. |

| 19 October 1938 | Parts of the Czechoslovak State Railway (ČSD) | Only railways located in the regions annexed by the Deutsche Reich ("Sudetenland") |

| 23 March 1939 | Parts of the Lithuanian State Railway | Railways in Memelland |

| 1 November 1939 | Parts of the Polish State Railways (PKP) | Lines in regions that had been German to 1918 and in adjacent areas with a German-speaking minority |

| from 1940 | Parts of the Belgian Railways (NMBS/SNCB) | Gradual takeover of the regions ceded to Belgium in 1920 |

| 1941 | Parts of the Yugoslavian Railways (JŽ-ЈЖ) | Lines within the incorporated regions of Lower Styria and Upper Carniola |

| 1941 | Parts of the Soviet Railways (SŽD/СЖД) | Lines located in the pre-1939 Polish district of Białystok |

| Date of takeover | Name | Network length |

|---|---|---|

| 1 January 1938 | Lübeck-Büchen Railway (LBE) | 160.8 km |

| 1 January 1938 | Brunswick State Railway (BLE) | 109.5 km |

| 1 August 1938 | Lokalbahn Munich (LAG) | 187.7 km |

| 1 January 1939 | Lusatian Railway Company | 80.9 km |

| 1939 to 1940 | In former Austria: Schneeberg Railway, Schafberg Railway, Steyr Valley Railway, Lower Austrian Waldviertel Railway, Vienna–Aspang railway, Mühlkreis Railway | |

| 1940 | 9 former Czechoslovak private railways, which the DR had already taken over the operations of in October 1938 | |

| From 1940 | Railways in Luxembourg (Prince Henri Railway and Mining Company, William Luxembourg Railway Company, Luxemburg Narrow Gauge Railways) | |

| 1 January 1941 | Mecklenburg Frederick William Railway Company | 112.6 km |

| 1 January 1941 | Prignitz Railway | 61.5 km |

| 1 January 1941 | Wittenberge–Perleberg Railway | 10 km |

| 1 Mai 1941 | Eutin–Lübeck Railway Company (ELE) | 39.3 km |

| 1 August 1941 | Kreis Oldenburg Railway (KOE) | 72.3 km |

| 1 January 1943 | Toitz–Rustow–Loitz light railway | 7 km |

| 1 July 1943 | Schipkau–Finsterwald Railway Company | 33 km |

Holocaust

The logistics of the Reichsbahn were also an important factor during the Holocaust. Jews were transported like cattle to the concentration and extermination camps by the Deutsche Reichsbahn in trains of covered goods wagons, now known as Holocaust trains. These movements using cattle wagons from the goods station of the great Frankfurt Market Hall, for example, thus played a significant role in the genocide within the extermination machinery of the Holocaust. In 1997, the market erected a memorial plaque in recognition of this dark period of history.[13][14]

The following is an excerpt from the testimony of Holocaust scholar Raul Hilberg:

The Reichsbahn was ready to ship in principle any cargo in return for payment. And therefore, the basic key – price controlled key – was that Jews were going to be shipped to Treblinka, were going to be shipped to Auschwitz, Sobibor ... so long as the railroads were paid by the track kilometer, so many pfennigs per mile. The rate was the same throughout the war, with children under ten going at half-fare and children under four going free. Payment had to be made for only one way. The guards of course had to have return fare paid for them because they were going back to their place of origin ...[15]

Conditions in the wagons were inhumane because no water or food was provided, and sanitary arrangements were minimal, usually a bucket in a corner of the wagon. Although each wagon was intended to hold about 50 people, they were frequently overcrowded and holding 100 to 150 people. No heating was provided, so people could freeze in winter and overheat in summer. Deaths in the wagons were frequent among the young, old, sick, and disabled, especially as travel was slow and often lasted many days since the trains had low priority on the tracks. Their small amount of luggage was stored separately, sometimes at the station and never left with the train, but examined for valuables which were stolen or resold for profit.

Beginning in November 2007, a museum train, the "Train of Commemoration" (Zug der Erinnerung), began a 3,000 km (1,900 mi) tour of Germany as a rolling memorial to the thousands of youth and children who were deported from all over Europe, many via the Reichsbahn, to the camps. A certain amount of controversy has surrounded the train's tour through Germany, in part because of the apparent lack of cooperation on the part of Deutsche Bahn AG (DB AG) concerning such matters as compensation for the use of the DB AG's right of way (during the tour) and the stationing of the train, during its visit to Berlin, at the Ostbahnhof station instead of the more centrally located Hauptbahnhof main railway station. The tour was scheduled to end on 8 May 2008 (the 63rd anniversary of the end of the European portion of World War II) when the train arrived at Auschwitz. However, it continued to make appearances through 2009, and as of January 2010 the website requests visitors to look for further travel plans at the end of February.[16]

Rebuilding after 1945

German railways were heavily bombed by Allied RAF and USAAF bombers. Marshalling yards, bridges, repair shops, and service facilities were all destroyed. Fighter-bombers targeted locomotives and bombed them. As a result, trains were at a standstill in the spring of 1945. The cities of Hamburg, Munich, Nuremberg, Frankfort, Dusseldorf, Berlin, Leipzig, Dresden and others were affected. Stations were completely destroyed and wagons and carriage set on fire and destroyed. Bomb craters and blast seriously damaged the permanent way or rail track. The Allied forces of Occupation were put in charge and instantly had myriad problems regarding food, lack of housing, fuel, displaced persons and people on the move.

The Engineering Corps of British and American forces oversaw the partial rebuilding of the lines and cars with local labour from Prisoners-of-War, rubble women, and de-mobilized soldiers. Temporary wooden bridges were put up over destroyed spans. Multiple tracks were disassembled into one smaller working line, equipment assessed and rebuilt. In three months, the railway was working again in a rudimentary form. The Armies of Occupation needed the railways to move coal and the soon to be gathered agricultural harvest. Deutschebahn had a critical shortage of wagons, carriages and locomotives, so much so that the US gave war surplus engines to ensure the movement of freight.

Breakup of the Reichsbahn

With the end of the Second World War in 1945 those parts of the Deutsche Reichsbahn that were outside the new German borders laid down in the Potsdam Agreement were transferred to the ownership and administration of the states in whose territory they were situated. For example, on 27 April 1945, the Austrian railways became independent again as the Austrian State Railway (Österreichische Staatseisenbahn or ÖStB), later renamed as the Austrian Federal Railways (Österreichische Bundesbahnen or ÖBB) on 5 August 1947.

Railways in the occupation zones

Operational control of the rest of the DR was devolved to the respective zones of occupation so that the Reichsbahn legally existed in four parts until 1949.

US Zone

In the American Zone the Reichsbahn divisions of Augsburg, Frankfurt am Main, Kassel, Munich, Regensburg and Stuttgart (for the railways in Württemberg-Baden) were subordinated to the Senior Control Office US Zone (Oberbetriebsleitung United States Zone) in Frankfurt.

British Zone

The Reichsbahn divisions of Essen, Hamburg, Hanover, Cologne, Münster (Westfalen) and Wuppertal were grouped into the Reichsbahn-Generaldirektion in the British Zone under Director General Max Leibbrand in Bielefeld.

French Zone

In the French Occupation Zone, the railways were grouped into the Operating Association of the Southwest German Railways (Betriebsvereinigung der Südwestdeutschen Eisenbahnen) with its headquarters in Speyer. The Operating Association included the railway divisions of Karlsruhe (in the US Zone), Mainz and Saarbrücken. After the Saarland was transferred from the French Zone and was given its own state railway – the Railways of the Saarland (Eisenbahnen des Saarlandes) – the rest of the network of the Saarbrücken division went into the new Trier division. After the Deutsche Bundesbahn was formed this Operating Association was merged with it.

Soviet Zone

The Soviet zone of occupation became a self-declared socialist state, the German Democratic Republic (commonly known as East Germany), on 7 October 1949. One month prior, on 7 September 1949, the railway systems in the three western zones (the Federal Republic of Germany), were reunified and renamed the Deutsche Bundesbahn (DB – German Federal Railways).

On the formation of East Germany on 7 October 1949, the railway system in the Soviet Zone retained the name Deutsche Reichsbahn (DR), despite the connotations of the word "Reich". This was due to the designation of the Reichsbahn in postwar treaties and military protocols as the railway operator in West Berlin, a role it retained until the creation of the unified DBAG at the beginning of 1994.

Bizone and creation of the DB

To conform to the formation of the Bizone in 1946 the Head Office of the Railways of the American and British Occupation Regions (Hauptverwaltung der Eisenbahnen des amerikanischen und britischen Besatzungsgebiets) was created. In 1947 it moved its headquarters to Offenbach am Main and called itself the Deutsche Reichsbahn in the United Economic Region (Deutsche Reichsbahn im Vereinigten Wirtschaftsgebiet). Following the foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany, it was renamed Deutsche Bundesbahn.

East German Deutsche Reichsbahn

In the post-war years, the DR in East Germany continued to develop independently of the DB, but very much in parallel. The locomotive classification scheme, based on that of the DRG, was extended. The production, conversion and development of steam locomotives initially continued in earnest; older, especially ex-Länderbahn classes being rationalised and withdrawn from service. A major conversion (Rekonstruktion) programme to update steam locomotives and rectify flawed, mainly wartime austerity, classes was carried out in the 1950s. Gradually, however, they were replaced by the more economical and easier-to-maintain diesel and electric classes. In general this happened rather later than in the West. In 1970, the DR renumbered its locomotives in order to conform to new computerised data standards.

On 3 October 1990, the GDR states acceded to the Federal Republic of Germany. Initially the two railway administrations continued to operate separately, albeit with increasing cooperation, and in 1994 they were merged to form the new Deutsche Bahn.

See also

References

- Mierzejewski, Alfred C. (2014). The Most Valuable Asset of the Reich: A History of the German National Railway. Vol. 1: 1920–1932. UNC Press Books. pp. v, xi–xii, 26. ISBN 978-1469620206.

- Zeller, Thomas (2007). Driving Germany: The Landscape of the German Autobahn, 1930–1970. Bergbahn Books. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-84545-309-1.

- Germany's Economy, Currency and Finance: A Study Addressed by Order of the German Government to the Committees of Experts, as Appointed by the Reparations Commission. Zentral-Verlag GmbH, 1924, pp. 4, 98 and 99.

- Anastasiadou, Irene (2011). Constructing Iron Europe: Transnationalism and Railways in the Interbellum. Amsterdam University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-9052603926.

- Information about railroad, history and technology of German state railway Archived 2006-04-08 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- Constitution of the Deutsches Reich Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine affecting railways. (in German)

- Law relating to the state treaty for the transfer of state railways to the Reich Archived 2012-02-16 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- Act for the creation of the "Deutsche Reichsbahn" company Archived 2012-02-16 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- Alfred C. Mierzejewski: The most valuable asset of the Reich. A history of the German National Railway. Vol. 1: 1920–1932. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill / London 1999, p. 26

- Resistance of the Heart. Rudgers University Press, New Jersey, 1996, .p.44.

- Schlag nach! – Wissenswerte Tatsachen aus allen Gebieten. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig, 1938, p. 341.

- Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Bundesarchiv

- Gedenktafel an der Großmarkthalle Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, dokumentiert beim Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Karmeliterkloster, Frankfurt am Main

- "Auf dem deutschen Schienennetz nach Auschwitz: 11000 Kinder" [On the German railway network to Auschwitz: 11,000 children] (in German). Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Lanzmann, Claude (1995). Shoah: The Complete Text of the Acclaimed Holocaust Film. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80665-7.

- "'Train of Commemoration' Travels Through Germany". Zug der Erinnerung e.V. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

Sources

- Roland Beier, Hans Sternhart: Deutsche Reichsbahn in Österreich 1938–1945 (–1953). Internationales Archiv für Lokomotivgeschichte Vol 14, Slezak, Wien, 1999, ISBN 3-85416-186-7

- Alfred C. Mierzejewski: The Most Valuable Asset of the Reich: A History of the German National Railway.

- Vol 1: 1920–1932, Chapel Hill und London, The University of North Carolina Press 1999

- Vol 2: 1933–1945, Chapel Hill und London, The University of North Carolina Press 2000

- Lothar Gall and Manfred Pohl: Die Eisenbahn in Deutschland. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich, 1999