Dexter King

Dexter Scott King (born January 30, 1961) is an American civil rights and animal rights activist and the second son of civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King. King is also the brother of Martin Luther King III, Bernice King, and Yolanda King; and also grandson of Martin Luther King Sr.

Dexter King | |

|---|---|

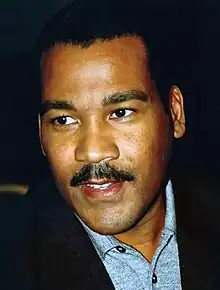

King in 1999 | |

| Born | Dexter Scott King January 30, 1961 |

| Education | Morehouse College |

| Occupation(s) | Civil rights activist, advocate |

| Known for | Son of Martin Luther King Jr. Chairman, The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change |

| Spouse |

Leah Weber (m. 2013) |

| Parent(s) | Martin Luther King Jr. (father) Coretta Scott King (mother) |

| Relatives | Yolanda Denise King (sister) Martin Luther King Sr. (paternal grandfather) Martin Luther King III (brother) Bernice Albertine King (sister) Alveda King (paternal first cousin) Edythe Scott Bagley (maternal aunt) James Albert King (paternal great-grandfather) |

Early life

King was born in 30 January 1961 at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta - Hughes Spalding Children's Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia[2] and named after the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, where his father was pastor before moving to the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia.[3] His eldest sister Yolanda watched after him.[4] He was seven years old when his father was assassinated. King and his siblings were assured an education thanks to the help of Harry Belafonte, who set up a trust fund for them years prior to their father's death.[5] King attended the Democratic National Convention in 1972, which led him to gain an interest in politics.[6]

Schooling

Dexter Scott King went to Spring Street Elementary School, in Midtown Atlanta, Georgia. He attended with his brother "Marty" and his sister Yolanda. Dexter, and his siblings, did not return to Spring Street Elementary for the Fall semester of 1968, following the assassination of their father on April 4, 1968.

King then attended The Galloway School in Atlanta.

Following his graduation from High school, King enrolled in Morehouse College, in Atlanta, Georgia, his late father's alma mater. He studied business administration, but did not graduate. He later became an actor and documentary filmmaker.

Activities

King splits his time between Atlanta, Georgia, where he serves as chairman of the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change, and Malibu, California.[7]

In May 1989, King's mother named the twenty-eight-year-old as her successor as president of the King Center. Before his mother's choice, King openly expressed interest in changing the King Center into "a West Point of nonviolent training".[8][9] Dexter Scott King served as president of the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change, but resigned only four months after taking the office after a dispute with her. He resumed the position in 1994, but the King Center's influence was sharply reduced by then.[7] As President, he cut the number of staff from 70 to 14 and shut down a child care center among a shift from conventional activities to prioritizing preserving his father's legacy. Reflecting, King admitted that the time was not right since he was "probably moving faster than the board was ready to".[10]

Dexter has been a dedicated vegan[11] and animal rights activist since the late 1980s.[12]

On August 28, 2013, he attended the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, the event at which his father delivered his I Have a Dream speech.

Film

Dexter Scott King portrayed his father and Civil rights movement activist Martin Luther King Jr. in the 2002 American television movie The Rosa Parks Story, and even voiced his father's 34-year-old self in the 1999 educational film, Our Friend, Martin.

Loyd Jowers trial

In 1997, 29 years after Martin Luther King Jr.'s death, Dexter met with James Earl Ray, the man imprisoned for his father's 1968 murder. When confronting him, King asked Ray, "I just want to ask you, for the record, um, did you kill my father?" Ray replied, "No-no I didn't." King then told Ray that he along with the rest of the King family believed him.[13][14] King and Ray had then discussed the latter's health and the actions of J. Edgar Hoover.[15] King also told him that his family believed in his testament of innocence and were seeking to help him. The two spoke privately after 25 minutes with reporters, and King asserted to reporters that he did not know who killed his father and that this uncertainty was the cause of their request for a new trial.[16] As he asserted that he did not believe Ray had any role in his father's death, he brought up evidence taken from the scene such as the murder weapon and concluded that Ray would not have disposed of it near the scene of the crime, calling his belief as having been in his "gut".[17]

At a 1999 press conference, Dexter was subsequently asked by a reporter, "there are many people out there who feel that as long as these conspirators remain nameless and faceless there is no true closure, and no justice". He replied:

No, he (Loyd Jowers) named the shooter. The shooter was the Memphis Police Department Officer, Lt. Earl Clark who he named as the killer. Once again, beyond that you had credible witnesses that named members of a Special Forces team who didn't have to act because the contract killer succeeded, with plausible denial, a Mafia contracted killer.[18]

His belief towards a conspiracy extended to President Lyndon B. Johnson.[19] He believed that with the evidence he was shown, there would be difficulty "for something of that magnitude to occur on his watch and he not be privy to it".[20] King pursued Andrew Young to get him involved, and Young changed his position on the assassination of his father after being visited by Dexter in the spring of 1997. His position had always been "that it didn't matter who killed Dr. King but what killed him".[21]

Family

Dexter charged The Atlanta Journal-Constitution with "viciously attacking" his family after the newspaper printed a claim by a German television program that his sister Bernice wanted $4,000 or $5,000 for a ten-minute interview, which King denied.[22]

King's mother, Coretta Scott King, died on January 30, 2006, at the age of 78 on his 45th birthday.

Dexter's elder sister, Yolanda, collapsed at the home of his best friend, Philip Madison Jones, on May 15, 2007. King called his aunt Christine King Ferris and reported that he had tried to save her, but was not successful and was transporting her to the hospital.[23] She could not be revived and died at the age of 51. Her family believes she had a heart condition. Dexter spoke to her just an hour before her death, and did not think much of it when she told him she was tired due to her "hectic" schedule.[24] In regards to his sister's passing and the role she had played in his life, King stated

She gave me permission. She allowed me to give myself permission to be me".[25]

It was reported in the Atlanta-Journal Constitution that in July 2013, Dexter married his fiancée Leah Weber in a private ceremony in California.[1]

Lawsuits

On July 11, 2008, Dexter King was sued by his sister Bernice Albertine King and brother Martin Luther King III; in addition, he was sued by Bernice King on behalf of the estate of Coretta King. The lawsuit alleged that Dexter improperly took funds from their parents' estate. On August 18, 2008, Dexter filed a countersuit stating his siblings had "breached their fiduciary and personal duties to the King Center in Atlanta and [their] father’s estate, misused assets belonging to the center, and kept money that should have been channeled back into the center and the estate".[26]

These lawsuits were filed in Fulton County, Georgia Superior Court[27] and were settled out of court in October 2009. In 2010, the three supported that year's census, seemingly indicating they had reaffirmed their relationships since the dispute.[28]

Films

Acting

King (1978)

King Holiday Music Video by The King Dream Chorus (1986)

Television

- 1-800-Missing, Lost Sister episode (2004)

- The Rosa Parks Story

- Our Friend, Martin (1999)

Literary works

- Growing Up King: An Intimate Memoir (2003)

References

- Poole, Sheila; Ernie Suggs (July 15, 2013). "Dexter King marries longtime girlfriend Leah Weber". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- King, Dexter Scott; Wiley, Ralph (2003-01-07). Growing Up King: An Intimate Memoir. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7595-2733-1.

- "King, Dexter Scott". The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. 2017-06-12. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- "First Christmas without him. Inside MLK's home in 1968". Youtube.

- "King's Kids Assured Education by Belafonte". Jet. April 18, 1968.

- Dexter Scott King. Ebony. January 1987.

- Firestone, David. "A civil rights group suspends, then reinstates, its president." The New York Times, July 26, 2001. Retrieved on 2008-08-28.

- "Rev. King's Son, Dexter, Resigns From Position as President of the King Center". Jet. August 28, 1989.

- "Son Dexter To Take Reign of The King Center in Atlanta". Jet. February 6, 1989.

- Dyson, p. 270.

- "A King Among Men," in Vegetarian Times, October 1995, Issue 218, p. 128.

- "taintedgreen.com".

- Today in History March 27 at Youtube

- Sack, Kevin (28 March 1997). "Dr. King's Son Says Family Believes Ray Is Innocent". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Harrison, Eric (March 28, 1997). "King's Son Meets Ray, Agrees He's Not Assassin". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- Dexter King Visits James Earl Ray in Prison; Says He Believes Ray is Innocent. Jet. April 14, 1997.

- Who Killed King?. Ebony. May 1997.

- "The Transcription of the King Family Press Conference on the MLK Assassination Trial Verdict". Archived from the original on September 1, 2009.

- Sack, Kevin (June 20, 1997). "Son of Dr. King Asserts L.B.J. Role in Plot". The New York Times.

- "Dexter King: I Think LBJ Knew About Assassination". Orlando Sentinel. June 20, 1997.

- Curry, pp. 489-490.

- Dyson, p. 261.

- Farris, p. 189.

- Haines, Errin (May 24, 2007). "Hundreds Mourn Eldest of King Children". The Washington Post.

- "Hundreds pay tribute to Yolanda King". USA Today. May 24, 2007.

- "AJC Homepage".

- "EarthLink - Top News". enews.earthlink.net.

- "2010 Census Message: The King Family". Youtube. May 4, 2010. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.

Works cited

- Dyson, Michael Eric (2000). I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King Jr. Free Press. ISBN 978-0684867762.

- Curry, George (2003). The Best of Emerge Magazine. One World/Ballantine. ISBN 978-0345462282.

External links

- MLK Conspiracy Trial (Scroll down to questions and answers by Dexter King):

- King family lawsuit called ‘disheartening’ Archived 2012-01-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Appearances on C-SPAN