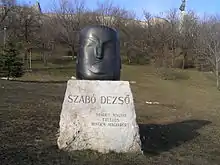

Dezső Szabó (writer)

Dezső Szabó (born June 10, 1879 in Kolozsvár, Austria-Hungary (present-day Cluj-Napoca, Romania), died January 5, 1945 in Budapest) was a Hungarian linguist, writer, noted mainly for his three-volume novel "Az elsodort falu" ("The Eroded Village") and his pamphlets.[1] Szabó's oeuvre is contradictory, some consider it as the peak of Hungarian expressionist prose,[2] others call it one of the first "pioneers of Magyar populist literature".[3] He was a Nobel Prize nominee in 1935.[4] He is also known for his anti-semitic views.

Szabó came to live in Budapest in 1918 and started publishing short essays in the literary revue Nyugat which was the leading newspaper of Hungary's intellectuals.[5] He had a great success with his pamphlet criticizing István Tisza, the liberal-conservative prime minister of Hungary. Due to this writing he became one of the leading figures of Hungarian progressive intellectuals.[6]

Initially he supported the Hungarian Revolution of 1918. Arthur Koestler, at the time a high school pupil in Budapest, recalls Szabó as one of the new teachers brought to his school by the revolutionary regime – "A shy, soft spoken, somewhat absent-minded man, he told us of a subject more faraway than the Moon: the daily life of hired agricultural workers in the countryside" [7]

Support for the revolution was, however, a brief interlude in Szabó's life, and he soon developed into an outspoken and vehement opponent of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic proclaimed by Béla Kun. He proclaimed to attack not the revolution itself, which was according to him unnecessary, but the "corruption of the revolution".[8]

He was quick to become a well-known and highly influential and energetic writer, gaining fame for his 1919 "Az elsodort falu" ("The Eroded Village"), an expressionist work espousing the idea that hope for a Hungarian renaissance lay in the peasant class, as opposed to the middle class which Szabó believed was "corrupted by the mentalities of the assimilated Germans and Jews".[9] Though he published many later books, this was considered as the peak of his literary achievements. Although the views of the novel is considered later unrealistic, stylistically it is still remarkable.[2]

He was not only the opponent of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, but later became one of the greatest critic of the conservative Horthy-era. He called the system "polecat-course", and his critic included democratic, antisemitic, progressive and conservative reasoning as well according to his contradictious personality.[10]

Historian Joseph Varga wrote:[11] "Szabo passionately represented the idea that the unique characteristics of the Magyar race and its national uniqueness could only be ensured through the Magyar peasantry. To him, the people were the peasants, its best characteristics and virtues were embodied in the peasantry, a significant improvement in the financial and cultural status of the Magyar peasantry was an historical necessity, in the interest of the entire nation [since] the peasantry was the sole social segment that remained true to Hungary’s Christian and national traditions through the revolutions of 1918 and 1919".

Szabó has been considered the first "intellectual anti-Semite among Hungarian writers",[3] and he was a regular contributor to the journal Virradat, one of the most rabidly anti-semitic papers of the inter-war period, in which he published no less than 44 articles during three years. These articles were couched in highly apocalyptic and alarmist tones, reprimanding the Hungarian nation for its "feebleness".

He was against the influence of Jews and Germans in Hungary, and although he proclaimed himself a non-anti-semitic, because of his articles and views cited above, he is considered to be anti-semitic. Due to this, there is also an accusation that Szabó explicitly called for the physical extermination of the Hungarian Jews. According to Yehuda Marton, an Israeli-Hungarian scholar who wrote the article about Szabó in the Hebrew Encyclopedia, Szabó did make such a call for extermination at a public meeting in 1921.[12] Apologists for the writer note that in "The Eroded Village" Miklós (a key figure of this main work) says to an old Jewish friend: "If you should know that all my anger comes out from that I know that we depend on each other, because I love you". In an other book he also wrote "I consider the honest Hungarian-Jew cooperation as a must for the two races and the foundation of a more human future".[8]

At the same time Szabó was also vehemently anti-German, embarking in 1923 on a "Campaign to eradicate German influence in Hungary". After 1932 he was also outspokenly opposed to the Arrow Cross Party, the Hungarists—without abandoning his anti-semitic views. This combination of views was due to his own specific brand of racism, which Szabó termed "The Apotheosis of the Hungarian Race".

Szabó died in January 1945, during the siege of Budapest by the Soviet Army.

Works

- Az Elsodort Falu (1918)

- Csodálatos élet (1920)

- Jaj! (1925)

- Feltámadás Makucskán´ (1925)

- Karácsony Kolozsvárt (1931)

References

- Nagy, Péter. A pamflet Michalengalója. In: Szabó, Dezső "A magyar káosz". Szépirodalmi Kiadó, 1990. p.17

- Hegedüs, Géza, A magyar irodalom arcképcsarnoka

- Lukacs, John. Budapest 1900. Grove Press, 1994. p.168

- Official Nomination Archive

- MacDonald, Agnes, Generation West : Hungarian modernism and the writers of the Nyugat review, 2008. p. 1.

- Nagy, Péter. A pamflet Michalengalója. In: Szabó, Dezső "A magyar káosz". Szépirodalmi Kiadó, 1990. p.6-7.

- Arthur Koestler, "Arrow in the Blue – An Autobiography", London, 1953, Ch. 8

- Szabó, Dezső. Megered az eső. Lazi Könyvkiadó, 2012. p.236

- Held, Joseph. Columbia History of Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Columbia University Press, 1993. p. 196

- Nagy, Péter. A pamflet Michalengalója. In: Szabó, Dezső "A magyar káosz". Szépirodalmi Kiadó, 1990. p.5-17.

- Joseph Varga, "GUILTY NATION or UNWILLING ALLY? A short history of Hungary and the Danubian basin 1918–1939"

- Yehuda Marton, Hebrew Encyclopedia, Jerusalem, 1974, Volume 25 p. 422 (in Hebrew)