Dictyostelium discoideum

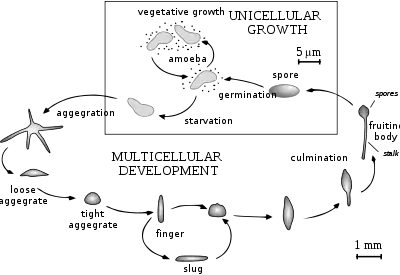

Dictyostelium discoideum is a species of soil-dwelling amoeba belonging to the phylum Amoebozoa, infraphylum Mycetozoa. Commonly referred to as slime mold, D. discoideum is a eukaryote that transitions from a collection of unicellular amoebae into a multicellular slug and then into a fruiting body within its lifetime. Its unique asexual life cycle consists of four stages: vegetative, aggregation, migration, and culmination. The life cycle of D. discoideum is relatively short, which allows for timely viewing of all stages. The cells involved in the life cycle undergo movement, chemical signaling, and development, which are applicable to human cancer research. The simplicity of its life cycle makes D. discoideum a valuable model organism to study genetic, cellular, and biochemical processes in other organisms.[2]

| Dictyostelium discoideum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fruiting bodies of D. discoideum | |

| A migrating D. discoideum whose boundary is colored by curvature, scale bar: 5 µm, duration: 22 seconds | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Amoebozoa |

| Class: | Dictyostelia |

| Order: | Dictyosteliida |

| Family: | Dictyosteliidae |

| Genus: | Dictyostelium |

| Species: | D. discoideum |

| Binomial name | |

| Dictyostelium discoideum | |

Natural habitat and diet

In the wild, D. discoideum can be found in soil and moist leaf litter. Its primary diet consists of bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, found in the soil and decaying organic matter. Uninucleate amoebae of D. discoideum consume bacteria found in their natural habitat, which includes deciduous forest soil and decaying leaves.[3]

Life cycle and reproduction

The life cycle of D. discoideum begins when spores are released from a mature sorocarp (fruiting body). Myxamoebae hatch from the spores under warm and moist conditions. During their vegetative stage, the myxamoebae divide by mitosis as they feed on bacteria. The bacteria secrete folic acid, which attracts the myxamoebae. When the supply of bacteria is depleted, the myxamoebae enter the aggregation stage.

During aggregation, starvation initiates the production of protein compounds such as glycoproteins and adenylyl cyclase.[4] The glycoproteins allow for cell-cell adhesion, and adenylyl cyclase creates cyclic AMP. Cyclic AMP is secreted by the amoebae to attract neighboring cells to a central location. As they move toward the signal, they bump into each other and stick together by the use of glycoprotein adhesion molecules.

The migration stage begins once the amoebae have formed a tight aggregate and the elongated mound of cells tips over to lie flat on the ground. The amoebae work together as a motile pseudoplasmodium, also known as a slug. The slug is about 2–4 mm long, composed of up to 100,000 cells,[5] and is capable of movement by producing a cellulose sheath in its anterior cells through which the slug moves.[6] Part of this sheath is left behind as a slimy trail as it moves toward attractants such as light, heat, and humidity in a forward-only direction.[6] Cyclic AMP and a substance called differentiation-inducing factor, help to form different cell types.[6] The slug becomes differentiated into prestalk and prespore cells that move to the anterior and posterior ends, respectively. Once the slug has found a suitable environment, the anterior end of the slug forms the stalk of the fruiting body and the posterior end forms the spores of the fruiting body.[6] Anterior-like cells, which have only been recently discovered, are also dispersed throughout the posterior region of the slug. These anterior-like cells form the very bottom of the fruiting body and the caps of the spores.[6] After the slug settles into one spot, the posterior end spreads out with the anterior end raised in the air, forming what is called the "Mexican hat", and the culmination stage begins.

The prestalk cells and prespore cells switch positions in the culmination stage to form the mature fruiting body.[6] The anterior end of the Mexican hat forms a cellulose tube, which allows the more posterior cells to move up the outside of the tube to the top, and the prestalk cells move down.[6] This rearrangement forms the stalk of the fruiting body made up of the cells from the anterior end of the slug, and the cells from the posterior end of the slug are on the top and now form the spores of the fruiting body. At the end of this 8– to 10-hour process, the mature fruiting body is fully formed.[6] This fruiting body is 1–2 mm tall and is now able to start the entire cycle over again by releasing the mature spores that become myxamoebae.

Sexual reproduction

Although D. discoideum generally reproduces asexually, D. discoideum is still capable of sexual reproduction if certain conditions are met. D. discoideum has three different mating types and studies have identified the sex locus that specifies these three mating types. Type I strains are specified by the gene called MatA, Type II strains have three different genes: MatB (homologous to Mat A), Mat C, and Mat D, and Type III strains have Mat S and Mat T genes (which are homologous to Mat C and Mat D).[7] These sexes can only mate with the two different sexes and not with its own.[7]

When incubated with their bacterial food supply, heterothallic or homothallic sexual development can occur, resulting in the formation of a diploid zygote.[8][9] Heterothallic mating occurs when two amoebae of different mating types are present in a dark and wet environment, where they can fuse during aggregation to form a giant zygote cell. The giant cell then releases cAMP to attract other cells, then engulfs the other cells cannibalistically in the aggregate. The consumed cells serve to encase the whole aggregate in a thick, cellulose wall to protect it. This is known as a macrocyst. Inside the macrocyst, the giant cell divides first through meiosis, then through mitosis to produce many haploid amoebae that will be released to feed as normal amoebae would. Homothallic D. discoideum strains AC4 and ZA3A are also able to produce macrocysts.[10] Each of these strains, unlike heterothallic strains, likely express both mating type alleles (matA and mata). While sexual reproduction is possible, it is very rare to see successful germination of a D. discoideum macrocyst under laboratory conditions. Nevertheless, recombination is widespread within D. discoideum natural populations, indicating that sex is likely an important aspect of their life cycle.[9]

Use as a model organism

Because many of its genes are homologous to human genes, yet its life cycle is simple, D. discoideum is commonly used as a model organism. It can be observed at organismic, cellular, and molecular levels primarily because of their restricted number of cell types and behaviors, and their rapid growth.[6] It is used to study cell differentiation, chemotaxis, and apoptosis, which are all normal cellular processes. It is also used to study other aspects of development, including cell sorting, pattern formation, phagocytosis, motility, and signal transduction.[11] These processes and aspects of development are either absent or too difficult to view in other model organisms. D. discoideum is closely related to higher metazoans. It carries similar genes and pathways, making it a good candidate for gene knockout.[12]

The cell differentiation process occurs when a cell becomes more specialized to develop into a multicellular organism. Changes in size, shape, metabolic activities, and responsiveness can occur as a result of adjustments in gene expression. Cell diversity and differentiation, in this species, involves decisions made from cell-cell interactions in pathways to either stalk cells or spore cells.[13] These cell fates depend on their environment and pattern formation. Therefore, the organism is an excellent model for studying cell differentiation.

Chemotaxis is defined as a passage of an organism toward or away from a chemical stimulus along a chemical concentration gradient. Certain organisms demonstrate chemotaxis when they move toward a supply of nutrients. In D. discoideum, the amoeba secretes the signal, cAMP, out of the cell, attracting other amoebae to migrate toward the source. Every amoeba moves toward a central amoeba, the one dispensing the greatest amount of cAMP secretions. The secretion of the cAMP is then exhibited by all amoebae and is a call for them to begin aggregation. These chemical emissions and amoeba movement occur every six minutes. The amoebae move toward the concentration gradient for 60 seconds and stop until the next secretion is sent out. This behavior of individual cells tends to cause oscillations in a group of cells, and chemical waves of varying cAMP concentration propagate through the group in spirals.[14]: 174–175

An elegant set of mathematical equations that reproduces the spirals and the streaming patterns of D. discoideum was discovered by mathematical biologists Thomas Höfer and Martin Boerlijst. Mathematical biologist Cornelis J. Weijer has proven that similar equations can model its movement. The equations of these patterns are mainly influenced by the density of the amoeba population, the rate of the production of cyclic AMP and the sensitivity of individual amoebas to cyclic AMP. The spiraling pattern is formed by amoebas at the centre of a colony who rotate as they send out waves of cyclic AMP.[15][16]

The use of cAMP as a chemotactic agent is not established in any other organism. In developmental biology, this is one of the comprehensible examples of chemotaxis, which is important for an understanding of human inflammation, arthritis, asthma, lymphocyte trafficking, and axon guidance. Phagocytosis is used in immune surveillance and antigen presentation, while cell-type determination, cell sorting, and pattern formation are basic features of embryogenesis that may be studied with these organisms.[6]

Note, however, that cAMP oscillations may not be necessary for the collective cell migration at multicellular stages. A study has found that cAMP-mediated signaling changes from propagating waves to a steady state at a multicellular stage of D. discoideum.[17]

Thermotaxis is movement along a gradient of temperature. The slugs have been shown to migrate along extremely shallow gradients of only 0.05 °C/cm, but the direction chosen is complicated; it seems to be away from a temperature about 2 °C below the temperature to which they had been acclimated. This complicated behavior has been analyzed by computer modeling of the behavior and the periodic pattern of temperature changes in soil caused by daily changes in air temperature. The conclusion is that the behavior moves slugs a few centimeters below the soil surface up to the surface. This is an amazingly sophisticated behavior by a primitive organism with no apparent sense of gravity.[14]: 108–109

Apoptosis (programmed cell death) is a normal part of species development.[4] Apoptosis is necessary for the proper spacing and sculpting of complex organs. Around 20% of cells in D. discoideum altruistically sacrifice themselves in the formation of the mature fruiting body. During the pseudoplasmodium (slug or grex) stage of its life cycle, the organism has formed three main types of cells: prestalk, prespore, and anterior-like cells. During culmination, the prestalk cells secrete a cellulose coat and extend as a tube through the grex.[4] As they differentiate, they form vacuoles and enlarge, lifting up the prespore cells. The stalk cells undergo apoptosis and die as the prespore cells are lifted high above the substrate. The prespore cells then become spore cells, each one becoming a new myxamoeba upon dispersal.[6] This is an example of how apoptosis is used in the formation of a reproductive organ, the mature fruiting body.

A recent major contribution from Dictyostelium research has come from new techniques allowing the activity of individual genes to be visualised in living cells.[18] This has shown that transcription occurs in "bursts" or "pulses" (transcriptional bursting) rather than following simple probabilistic or continuous behaviour. Bursting transcription now appears to be conserved between bacteria and humans. Another remarkable feature of the organism is that it has sets of DNA repair enzymes found in human cells, which are lacking from many other popular metazoan model systems.[19] Defects in DNA repair lead to devastating human cancers, so the ability to study human repair proteins in a simple tractable model will prove invaluable.

Lab cultivation

This organism's ability to be easily cultivated in the laboratory[6] adds to its appeal as a model organism. While D. discoideum can be grown in liquid culture, it is usually grown in Petri dishes containing nutrient agar and the surfaces are kept moist. The cultures grow best at 22–24 °C (room temperature). D. discoideum feed primarily on E. coli, which is adequate for all stages of the life cycle. When the food supply is diminished, the myxamoebae aggregate to form pseudoplasmodia. Soon, the dish is covered with various stages of the life cycle. Checking the dish often allows for detailed observations of development. The cells can be harvested at any stage of development and grown quickly.

While cultivating D. discoideum in a laboratory, it is important to take into account its behavioral responses. For example, it has an affinity toward light, higher temperatures, high humidity, low ionic concentrations, and the acidic side of the pH gradient. Experiments are often done to see how manipulations of these parameters hinder, stop, or accelerate development. Variations of these parameters can alter the rate and viability of culture growth. Also, the fruiting bodies, being that this is the tallest stage of development, are very responsive to air currents and physical stimuli. It is unknown if there is a stimulus involved with spore release.

Protein expression studies

Detailed analysis of protein expression in Dictyostelium has been hampered by large shifts in the protein expression profile between different developmental stages and a general lack of commercially available antibodies for Dictyostelium antigens.[20] In 2013, a group at the Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre reported an antibody-free protein visualization standard for immunoblotting based on detection of MCCC1 using streptavidin conjugates.[21]

Legionnaire's disease

The bacterial genus Legionella includes the species that causes legionnaire's disease in humans. D. discoideum is also a host for Legionella and is a suitable model for studying the infection process.[22] Specifically, D. discoideum shares with mammalian host cells a similar cytoskeleton and cellular processes relevant to Legionella infection, including phagocytosis, membrane trafficking, endocytosis, vesicle sorting, and chemotaxis.

"Farming"

A 2011 report in Nature published findings that demonstrated a "primitive farming behaviour" in D. discoideum colonies.[23][24] Described as a "symbiosis" between D. discoideum and bacterial prey, about one-third of wild-collected D. discoideum colonies engaged in the "husbandry" of the bacteria when the bacteria were included within the slime mold fruiting bodies.[24] The incorporation of the bacteria into the fruiting bodies allows the "seeding" of the food source at the location of the spore dispersal, which is particularly valuable if the new location is low in food resources.[24] Colonies produced from the "farming" spores typically also show the same behavior when sporulating. This incorporation has a cost associated with it: Those colonies that do not consume all of the prey bacteria produce smaller spores that cannot disperse as widely. In addition, much less benefit exists for bacteria-containing spores that land in a food-rich region. This balance of the costs and benefits of the behavior may contribute to the fact that a minority of D. discoideum colonies engage in this practice.[23][24]

D. discoideum is known for eating Gram-positive, as well as Gram-negative bacteria, but some of the phagocytized bacteria, including some human pathogens,[25] are able to live in the amoebae and exit without killing the cell. When they enter the cell, where they reside, and when they leave the cell are not known. The research is not yet conclusive but it is possible to draw a general life cycle of D. discoideum adapted for farmer clones to better understand this symbiotic process.

In the picture, one can see the different stages. First, in the starvation stage, bacteria are enclosed within D. discoideum,[25] after entry into amoebae, in a phagosome the fusion with lysosomes is blocked and these unmatured phagosomes are surrounded by host cell organelles such as mitochondria, vesicles, and a multilayer membrane derived from the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) of amoebae. The role of the RER in the intracellular infection is not known, but the RER is not required as a source of proteins for the bacteria.[26] The bacteria reside within these phagosomes during the aggregation and the multicellular development stages. The amoebae preserve their individuality and each amoeba has its own bacterium. During the culmination stage, when the spores are produced, the bacteria pass from the cell to the sorus with the help of a cytoskeletal structure that prevents host cell destruction.[27] Some results suggest the bacteria exploit the exocytosis without killing the cell.[27] Free-living amoebae seem to play a crucial role for persistence and dispersal of some pathogens in the environment. Transient association with amoebae has been reported for a number of different bacteria, including Legionella pneumophila, many Mycobacterium species, Francisella tularensis, and Escherichia coli, among others.[26] Agriculture seems to play a crucial role for pathogens' survival, as they can live and replicate inside D. discoideum, making husbandry. Nature’s report has made an important advance in the knowledge of amoebic behavior, and the famous Spanish phrase translated as “you are more stupid than an amoeba” is losing the sense because amoebae are an excellent example of social behavior with an amazing coordination and sense of sacrifice for the benefit of the species.

Sentinel cells

Sentinel cells in Dictyostelium discoideum are phagocytic cells responsible for removing toxic material from the slug stage of the social cycle. Generally round in shape, these cells are present within the slug sheath where they are found to be circulating freely. The detoxification process occurs when these cells engulf toxins and pathogens within the slug through phagocytosis. Then, the cells clump into groups of five to ten cells, which then attach to the inner sheath of the slug. The sheath is sloughed off as the slug migrates to a new site in search of food bacteria.

Sentinel cells make up approximately 1% of the total number of slug cells, and the number of sentinel cells remains constant even as they are being released. This indicates a constant regeneration of sentinel cells within the slugs as they are being removed along with toxins and pathogens. Sentinel cells are present in the slug even when there are no toxins or pathogens to be removed. Sentinel cells have been located in five other species of Dictyostelia, which suggests that sentinel cells can be described as a general characteristic of the innate immune system in social amoebae.[28]

Effects of farming status on sentinel cells

The number of sentinel cells varies depending on the farming status of wild D. discoideum. When exposed to a toxic environment created by the use of ethidium bromide, it was shown that the number of sentinel cells per millimeter was lower for farmers than non-farmers. This was concluded by observing the trails left behind as the slugs migrated and counting the number of sentinel cells present in a millimeter. However, the number of sentinel cells does not affect the spore production and viability in farmers. Farmers exposed to a toxic environment produce the same number of spores as farmers in a non-toxic environment, and the spore viability was the same between the farmers and non-farmers. When Clade 2 Burkholderia, or farmer-associated bacteria, are removed from the farmers, spore production and viability were similar to that of the non-farmers. Thus, it is suggested that bacteria carried by the farmers provide an additional role of protection for the farmers against potential harm due to toxins or pathogens.[29]

Classification and phylogeny

In older classifications, Dictyostelium was placed in the defunct polyphyletic class Acrasiomycetes. This was a class of cellular slime molds, which was characterized by the aggregation of individual amoebae into a multicellular fruiting body, making it an important factor that related the acrasids to the dictyostelids.[30]

More recent genomic studies have shown that Dictyostelium has maintained more of its ancestral genome diversity than plants and animals, although proteome-based phylogeny confirms that amoebozoa diverged from the animal–fungal lineage after the plant–animal split.[31] Subclass Dictyosteliidae, order Dictyosteliales is a monophyletic assemblage within the Mycetozoa, a group that includes the protostelid, dictyostelid, and myxogastrid slime molds. Elongation factor-1α (EF-1α) data analyses support Mycetozoa as a monophyletic group, though rRNA trees place it as a polyphyletic group. Further, these data support the idea that the dictyostelid and myxogastrid are more closely related to each other than they are the protostelids. EF-1α analysis also placed the Mycetozoa as the immediate outgroup for the animal-fungal clade.[32] Latest phylogenetic data place dictyostelids firmly within supergroup Amoebozoa, along with myxomycetes. Meanwhile, protostelids have turned out to be polyphyletic, their stalked fruiting bodies a convergent feature of multiple unrelated lineages.[33]

Genome

The D. discoideum genome sequencing project was completed and published in 2005 by an international collaboration of institutes. This was the first free-living protozoan genome to be fully sequenced. D. discoideum consists of a 34-Mb haploid genome with a base composition of 77% [A+T] and contains six chromosomes that encode around 12,500 proteins.[3] Sequencing of the D. discoideum genome provides a more intricate study of its cellular and developmental biology.

Tandem repeats of trinucleotides are very abundant in this genome; one class of the genome is clustered, leading researchers to believe it serves as centromeres. The repeats correspond to repeated sequences of amino acids and are thought to be expanded by nucleotide expansion.[3] Expansion of trinucleotide repeats also occurs in humans, in general leading to many diseases. Learning how D. discoideum cells endure these amino acid repeats may provide insight to allow humans to tolerate them.

Every genome sequenced plays an important role in identifying genes that have been gained or lost over time. Comparative genomic studies allow for comparison of eukaryotic genomes. A phylogeny based on the proteome showed that the amoebozoa deviated from the animal-fungal lineage after the plant-animal split.[3] The D. discoideum genome is noteworthy because its many encoded proteins are commonly found in fungi, plants, and animals.[3]

Databases

- DictyBase - general genomic database about Dictyostelium discoideum

- Membranome database provides information about single-pass transmembrane proteins from Dictyostelium and several other organisms

References

- Raper, K.B. (1935). "Dictyostelium discoideum, a new species of slime mold from decaying forest leaves". Journal of Agricultural Research. 50: 135–147. Archived from the original on 2017-12-08. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- Pears, Catherine J.; Gross, Julian D. (2021-03-01). "Microbe Profile: Dictyostelium discoideum: model system for development, chemotaxis and biomedical research". Microbiology. 167 (3). doi:10.1099/mic.0.001040. ISSN 1350-0872. PMID 33646931. S2CID 232092012.

- Eichinger L; Noegel, AA (2003). "Crawling in to a new era – the Dictyostelium genome project". The EMBO Journal. 22 (9): 1941–1946. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg214. PMC 156086. PMID 12727861.

- Gilbert S.F. 2006. Developmental Biology. 8th ed. Sunderland (MA):Sinauer p. 36-39.

- Cooper, Geoffrey M (2000). "Chapter 1. An Overview of Cells and Cell Research". The Cell (Work in NCBI Bookshelf). Part I. Introduction (2nd ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates. Cells As Experimental Models. ISBN 978-0-87893-106-4.

- Tyler M.S. 2000. Developmental Biology: A guide for experimental study. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer. p. 31-34. ISBN 0-87893-843-5

- Bloomfield, Gareth; Skelton, Jason; Ivens, Alasdair; Tanaka, Yoshimasa; Kay, Robert R. (2010-12-10). "Sex Determination in the Social Amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum". Science. 330 (6010): 1533–1536. Bibcode:2010Sci...330.1533B. doi:10.1126/science.1197423. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 3648785. PMID 21148389.

- O'Day DH, Keszei A (May 2012). "Signalling and sex in the social amoebozoans". Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 87 (2): 313–29. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00200.x. PMID 21929567. S2CID 205599638.

- Flowers JM, Li SI, Stathos A, Saxer G, Ostrowski EA, Queller DC, Strassmann JE, Purugganan MD (July 2010). "Variation, sex, and social cooperation: molecular population genetics of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum". PLOS Genet. 6 (7): e1001013. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001013. PMC 2895654. PMID 20617172.

- Robson GE, Williams KL (April 1980). "The mating system of the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum". Curr. Genet. 1 (3): 229–32. doi:10.1007/BF00390948. PMID 24189663. S2CID 23172357.

- Dictybase, About Dictyostelium. [Online] (1, May, 2009). http://dictybase.org/

- Dilip K. Nag, Disruption of Four Kinesin Genes in Dictyostelium. [Online] (22, April, 2008). http://ukpmc.ac.uk/articlerender.cgi?artid=1529371 Archived 2012-07-29 at archive.today

- Kay R.R.; Garrod D.; Tilly R. (1978). "Requirements for cell differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum". Nature. 211 (5640): 58–60. Bibcode:1978Natur.271...58K. doi:10.1038/271058a0. PMID 203854. S2CID 4160546.

- Dusenbery, David B. (1996). Life at Small Scale. Scientific American Library. New York. ISBN 978-0-7167-5060-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ian Stewart (November 2000). "Biomathematics Patterns: Spiral Slime. MATHEMATICAL RECREATIONS by Ian Stewart. Finding mathematics in creatures great and small". Scientific American.

- Ian Stewart (2000). What Shape is a Snowflake? [Over sneeuwkristallen en zebrastrepen. De wereld volgens de wiskunde] (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Uniepers; Davidsfonds; Natuur & Techniek. pp. 96–97.

- Ueda, Masahiro; Masato Yasui; Morimoto, Yusuke V.; Hashimura, Hidenori (2019-01-24). "Collective cell migration of Dictyostelium without cAMP oscillations at multicellular stages". Communications Biology. 2 (1): 34. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0273-6. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 6345914. PMID 30701199.

- Chubb, JR; Trcek, T; Shenoy, SM; Singer, RH (2006). "Transcriptional pulsing of a developmental gene". Current Biology. 16 (10): 1018–25. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.092. PMC 4764056. PMID 16713960.

- Hudson J. J.; Hsu D. W.; Guo K.; Zhukovskaya N.; Liu P. H.; Williams J. G.; Pears C. J.; Lakin N. D. (2005). "DNA-PKcs-dependent signaling of DNA damage in Dictyostelium discoideum". Curr Biol. 15 (20): 1880–5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.039. PMID 16243037.

- "Immunoblotting: Equality for slime molds!". BioTechniques (paper). 55 (1): 9. July 2013.

- Davidson, Andrew J.; King, Jason S.; Insall, Robert H. (July 2013). "The use of strepavidin conjugates as immunoblot loading controls of mitochondrial markers for use with Dictyostelium discoidium". Benchmarks. BioTechniques (paper). 55 (1): 39–41. doi:10.2144/000114054. PMID 23834384.

- Bruhn H. 2008. Dictyostelium, a tractable model host organism for Legionella. In: Heuner K, Swanson M, editors. Legionella: Molecular Microbiology. Norwich (UK): Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-26-4

- "Amoebas show primitive farming behaviour as they travel", BBC News, 19 January 2011

- Brock DA, Douglas TE, Queller DC, Strassmann JE (20 January 2011). "Primitive agriculture in a social amoeba". Nature. 469 (7330): 393–396. Bibcode:2011Natur.469..393B. doi:10.1038/nature09668. PMID 21248849. S2CID 4333826.

- Clarke, Margaret (2010). "Recent insights into host-pathogen interactions from Dyctiostelium". Cellular Microbiology. 12 (3): 283–291. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01413.x. PMID 19919566.

- Molmeret M., Horn, M., Wagner, M., Abu Kwaik, Y (January 2005). "Primitive Amoebae as Training Grounds for Intracellular Bacterial Pathogens". Appl Environ Microbiol. 71 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.1.20-28.2005. PMC 544274. PMID 15640165.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grant P.Ottom Mary Y.Wu; Margaret Clarke; Hao Lu; O.Roger Anderson; Hubert Hilbi; Howard A. Shuman; Richard H. Kessin (11 November 2003). "Macroautophagy is dispensable for intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila in Dictyostelium discoideum". Molecular Microbiology. 51 (1): 63–72. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03826.x. PMID 14651611. S2CID 22801290.

- Chen, Guokai; Zhuchenko, Olga; Kuspa, Adam (2007-08-03). "Immune-like Phagocyte Activity in the Social Amoeba". Science. New York, NY. 317 (5838): 678–681. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..678C. doi:10.1126/science.1143991. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 3291017. PMID 17673666.

- Brock, Debra A.; Callison, W. Éamon; Strassmann, Joan E.; Queller, David C. (2016-04-27). "Sentinel cells, symbiotic bacteria and toxin resistance in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum". Proc. R. Soc. B. 283 (1829): 20152727. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2727. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4855374. PMID 27097923.

- Cavender J.C.; Spiegl F.; Swanson A. (2002). "Taxonomy, slime molds, and the questions we ask". The Mycological Society of America. 94 (6): 968–979. PMID 21156570.

- Eichenger L.; et al. (2005). "The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum". Nature. 435 (7038): 34–57. Bibcode:2005Natur.435...43E. doi:10.1038/nature03481. PMC 1352341. PMID 15875012.

- Baldauf S.L.; Doolittle W.F. (1997). "Origin and evolution of the slime molds (Mycetozoa)". PNAS. 94 (22): 12007–12012. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9412007B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.22.12007. PMC 23686. PMID 9342353.

- Shadwick, LL; Spiegel, FW; Shadwick, JD; Brown, MW; Silberman, JD (2009). "Eumycetozoa = Amoebozoa?: SSUrDNA Phylogeny of Protosteloid Slime Molds and Its Significance for the Amoebozoan Supergroup". PLOS ONE. 4 (8): e6754. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006754. PMC 2727795. PMID 19707546.