Differential (mechanical device)

A differential is a gear train with three drive shafts that has the property that the rotational speed of one shaft is the average of the speeds of the others. A common use of differentials is in motor vehicles, to allow the wheels at each end of a drive axle to rotate at different speeds while cornering. Other uses include clocks and analog computers.

Differentials can also provide a gear ratio between the input and output shafts (called the "axle ratio" or "diff ratio"). For example, many differentials in motor vehicles provide a gearing reduction by having fewer teeth on the pinion than the ring gear.

History

Milestones in the design or use of differentials include:

- 100 BCE–70 BCE: The Antikythera mechanism has been dated to this period. It was discovered in 1902 on a shipwreck by sponge divers, and modern research suggests that it used a differential gear to determine the angle between the ecliptic positions of the Sun and Moon, and thus the phase of the Moon.[1]

- c. 250 CE: Chinese engineer Ma Jun creates the first well-documented south-pointing chariot, a precursor to the compass. Its mechanism of action is unclear, though some 20th century engineers put forward the argument that it used a differential gear.[2]

- 1810: Rudolph Ackermann of Germany invents a four-wheel steering system for carriages, which some later writers mistakenly report as a differential.

- 1827: Modern automotive differential patented by watchmaker Onésiphore Pecqueur (1792–1852) of the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in France for use on a steam wagon.[3]

- 1874: Aveling and Porter of Rochester, Kent list a crane locomotive in their catalogue fitted with their patent differential gear on the rear axle.[4]

- 1876: James Starley of Coventry invents chain-drive differential for use on bicycles; invention later used on automobiles by Karl Benz.

- 1897: While building his Australian steam car, David Shearer made the first use of a differential in a motor vehicle.[5]

- 1958: Vernon Gleasman patents the Torsen limited-slip differential.[6]

Use in wheeled vehicles

Purpose

During cornering, the outer wheels of a vehicle must travel further than the inner wheels (since they are on a larger radius). This is easily accommodated when the wheels are not connected, however it becomes more difficult for the drive wheels, since both wheels are connected to the engine (usually via a transmission). Some vehicles (for example go-karts and trams) use axles without a differential, thus relying on wheel slip when cornering. However, for improved cornering abilities, many vehicles use a differential, which allows the two wheels to rotate at different speeds.

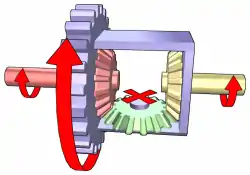

The purpose of a differential is to transfer the engine's power to the wheels while still allowing the wheels to rotate at different speeds when required. An illustration of the operating principle for a ring-and-pinion differential is shown below.

Differential operation while driving in a straight line:

Differential operation while driving in a straight line:

Input torque is applied to the ring gear (purple), which rotates the carrier (purple) at the same speed. When the resistance from both wheels is the same, the planet gear (green) doesn't rotate on its axis (although the gear and its pin are orbiting due to being attached to the carrier). This causes the sun gears (red and yellow) to rotate at the same speed, resulting in the car's wheels also rotating at the same speed. Differential operation while turning left:

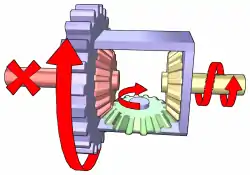

Differential operation while turning left:

Input torque is applied to the ring gear (purple), which rotates the carrier (purple) at the same speed. The left sun gear (red) provides more resistance than the right sun gear (yellow), which causes the planet gear (green) to rotate anti-clockwise. This produces slower rotation in the left sun gear and faster rotation in the right sun gear, resulting in the car's right wheel turning faster (and thus travelling farther) than the left wheel.

Ring-and-pinion design

.jpg.webp)

A relatively simple design of differential is used in rear-wheel drive vehicles, whereby a ring gear is driven by a pinion gear connected to the transmission. The functions of this design are to change the axis of rotation by 90 degrees (from the propshaft to the half-shafts) and provide a reduction in the gear ratio.

The components of the ring-and-pinion differential shown in the schematic diagram on the right are: 1. Output shafts (axles) 2. Drive gear 3. Output gears 4. Planetary gears 5. Carrier 6. Input gear 7. Input shaft (driveshaft)

Epicyclic design

An epicyclic differential uses epicyclic gearing to send certain proportions of torque to the front axle and the rear axle in an all-wheel drive vehicle. An advantage of the epicyclic design is that it is relatively compact width (when viewed along the axis of its input shaft).

Spur-gear design

.jpg.webp)

A spur-gear differential has an equal-sized spur gears at each end, each of which is connected to an output shaft.[7] The input torque (i.e. from the engine or transmission) is applied to the differential via the rotating carrier.[7] Pinion pairs are located within the carrier and rotate freely on pins supported by the carrier. The pinion pairs only mesh for the part of their length between the two spur gears, and rotate in opposite directions. The remaining length of a given pinion meshes with the nearer spur gear on its axle. Each pinion connects the associated spur gear to the other spur gear (via the other pinion). As the carrier is rotated (by the input torque), the relationship between the speeds of the input (i.e. the carrier) and that of the output shafts is the same as other types of open differentials.

Uses of spur-gear differentials include the Oldsmobile Toronado American front-wheel drive car.[7]

Locking differentials

Locking differentials have the ability to overcome the chief limitation of a standard open differential by essentially "locking" both wheels on an axle together as if on a common shaft. This forces both wheels to turn in unison, regardless of the traction (or lack thereof) available to either wheel individually. When this function is not required, the differential can be "unlocked" to function as a regular open differential.

Locking differentials are mostly used on off-road vehicles, to overcome low-grip and variable grip surfaces.

Limited-slip differentials

An undesirable side-effect of a regular ("open") differential is that it can send most of the power to the wheel with the lesser traction (grip).[8][9] In situation when one wheel has reduced grip (e.g. due to cornering forces or a low-grip surface under one wheel), an open differential can cause wheelspin in the tyre with less grip, while the tyre with more grip receives very little power to propel the vehicle forward.[10]

In order to avoid this situation, various designs of limited-slip differentials are used to limit the difference in power sent to each of the wheels.

Torque vectoring

Torque vectoring is a technology employed in automobile differentials that has the ability to vary the torque to each half-shaft with an electronic system; or in rail vehicles which achieve the same using individually motored wheels. In the case of automobiles, it is used to augment the stability or cornering ability of the vehicle.

Other uses

Non-automotive uses of differentials include performing analog arithmetic. Two of the differential's three shafts are made to rotate through angles that represent (are proportional to) two numbers, and the angle of the third shaft's rotation represents the sum or difference of the two input numbers. The earliest known use of a differential gear is in the Antikythera mechanism, circa 80 BCE, which used a differential gear to control a small sphere representing the Moon from the difference between the Sun and Moon position pointers. The ball was painted black and white in hemispheres, and graphically showed the phase of the Moon at a particular point in time.[1] An equation clock that used a differential for addition was made in 1720. In the 20th century, large assemblies of many differentials were used as analog computers, calculating, for example, the direction in which a gun should be aimed.[11]

Compass-like devices

Chinese south-pointing chariots may also have been very early applications of differentials. The chariot had a pointer which constantly pointed to the south, no matter how the chariot turned as it travelled. It could therefore be used as a type of compass. It is widely thought that a differential mechanism responded to any difference between the speeds of rotation of the two wheels of the chariot, and turned the pointer appropriately. However, the mechanism was not precise enough, and, after a few miles of travel, the dial could be pointing in the wrong direction.

Clocks

The earliest verified use of a differential was in a clock made by Joseph Williamson in 1720. It employed a differential to add the equation of time to local mean time, as determined by the clock mechanism, to produce solar time, which would have been the same as the reading of a sundial. During the 18th century, sundials were considered to show the "correct" time, so an ordinary clock would frequently have to be readjusted, even if it worked perfectly, because of seasonal variations in the equation of time. Williamson's and other equation clocks showed sundial time without needing readjustment. Nowadays, we consider clocks to be "correct" and sundials usually incorrect, so many sundials carry instructions about how to use their readings to obtain clock time.

Analogue computers

Differential analyzers, a type of mechanical analog computer, were used from approximately 1900 to 1950. These devices used differential gear trains to perform addition and subtraction.

The U.S. Navy Mk.1 gun fire control computer used about 160 differentials of the bevel-gear type.

Vehicle suspension

The Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity (both launched in 2004) used differential gears in their rocker-bogie suspensions to keep the rover body balanced as the wheels on the left and right move up and down over uneven terrain.[12] The Curiosity and Perseverance rovers used a differential bar instead of gears to perform the same function.[13]

See also

References

- Wright, M. T. (2007). "The Antikythera Mechanism Reconsidered" (PDF). Interdisciplinary Science Reviews. 32 (1): 27–43. Bibcode:2007ISRv...32...27W. doi:10.1179/030801807X163670. S2CID 54663891. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China. Taipei: Caves Books. 4 Part 2: 296–306.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "History of the Automobile". General Motors Canada. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- Preston, J.M. (1987). Aveling & Porter, Ltd. Rochester. North Kent Books. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-948305-03-7.

- "David Shearer's Steam Car at Mannum in 1897 – Australia's First – with World-First Differential". AdelaideAZ.com. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- "Inventor Of Automotive Technologies – Vernon Gleasman's Legacy". TheAutoChannel.com. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- "What Is a Spur Gear Differential?". SergeantClutchDiscountTransmission.com. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- Bonnick, Allan (2001). Automotive Computer Controlled Systems. p. 22. ISBN 9780750650892.

- Bonnick, Allan (2008). Automotive Science and Mathematics. p. 123. ISBN 9780750685221.

- Chocholek, S. E. (1988). "The Development of a Differential for the Improvement of Traction Control".

- Basic Mechanisms in Fire Control Computers, Part 1, Shafts Gears Cams and Differentials, posted as 'U.S. Navy Vintage Fire Control Computers' (Training Film). U.S. Navy. 1953. Event occurs at 37 seconds. MN-6783a. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- "Rover Wheels". Mars.NASA.gov. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- "Curiosity Mobility System, Labeled". Planetary.org. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

External links

- A video of a 3D model of an open differential

- Popular Science, May 1946, How Your Car Turns Corners, a large article with numerous illustrations on how differentials work