Digital art

Digital art refers to any artistic work or practice that uses digital technology as part of the creative or presentation process. It can also refer to computational art that uses and engages with digital media.[2]

Since the 1960s, various names have been used to describe digital art, including computer art, electronic art, multimedia art[3] and new media art.[4][5]

History

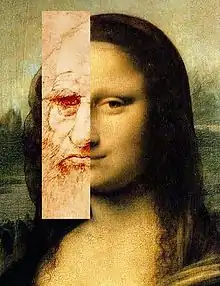

John Whitney developed the first computer-generated art in the early 1960s by utilizing mathematical operations to create art.[6] In 1963, Ivan Sutherland invented the first user interactive computer-graphics interface known as Sketchpad.[7] Between 1974 and 1977, Salvador Dalí created two big canvases of Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea which at a distance of 20 meters is transformed into the portrait of Abraham Lincoln (Homage to Rothko)[8] and prints of Lincoln in Dalivision based on a portrait of Abraham Lincoln processed on a computer by Leon Harmon published in "The Recognition of Faces".[9] The technique is similar to what later became known as photographic mosaics.

Andy Warhol created digital art using an Amiga where the computer was publicly introduced at the Lincoln Center, New York, in July 1985. An image of Debbie Harry was captured in monochrome from a video camera and digitized into a graphics program called ProPaint. Warhol manipulated the image by adding color using flood fills.[10][11]

Art that uses digital tools

Digital art can be purely computer-generated (such as fractals and algorithmic art) or taken from other sources, such as a scanned photograph or an image drawn using vector graphics software using a mouse or graphics tablet. Artworks are considered digital paintings when created similarly to non-digital paintings but using software on a computer platform and digitally outputting the resulting image as painted on canvas.

Amidst varied opinions on the pros and cons of digital technology on the arts, there seems to be a strong consensus within the digital art community that it has created a "vast expansion of the creative sphere", i.e., that it has greatly broadened the creative opportunities available to professional and non-professional artists alike.[12]

Computer-generated visual media

Digital visual art consists of either 2D visual information displayed on an electronic visual display or information mathematically translated into 3D information viewed through perspective projection on an electronic visual display. The simplest is 2D computer graphics which reflect how you might draw using a pencil and a piece of paper. In this case, however, the image is on the computer screen, and the instrument you draw with might be a tablet stylus or a mouse. What is generated on your screen might appear to be drawn with a pencil, pen, or paintbrush. The second kind is 3D computer graphics, where the screen becomes a window into a virtual environment, where you arrange objects to be "photographed" by the computer. Typically 2D computer graphics use raster graphics as their primary means of source data representations, whereas 3D computer graphics use vector graphics in the creation of immersive virtual reality installations. A possible third paradigm is to generate art in 2D or 3D entirely through the execution of algorithms coded into computer programs. This can be considered the native art form of the computer, and an introduction to the history of which is available in an interview with computer art pioneer Frieder Nake.[13] Fractal art, Datamoshing, algorithmic art, and real-time generative art are examples.

Computer-generated 3D still imagery

3D graphics are created via the process of designing imagery from geometric shapes, polygons, or NURBS curves[14] to create three-dimensional objects and scenes for use in various media such as film, television, print, rapid prototyping, games/simulations, and special visual effects.

There are many software programs for doing this. The technology can enable collaboration, lending itself to sharing and augmenting by a creative effort similar to the open source movement and the creative commons in which users can collaborate on a project to create art.[15]

Pop surrealist artist Ray Caesar works in Maya (a 3D modeling software used for digital animation), using it to create his figures as well as the virtual realms in which they exist.

Computer-generated animated imagery

Computer-generated animations are animations created with a computer from digital models created by 3D artists or procedurally generated. The term is usually applied to works created entirely with a computer. Movies make heavy use of computer-generated graphics; they are called computer-generated imagery (CGI) in the film industry. In the 1990s and early 2000s, CGI advanced enough that, for the first time, it was possible to create realistic 3D computer animation, although films had been using extensive computer images since the mid-70s. A number of modern films have been noted for their heavy use of photo-realistic CGI.[16]

Digital painting

Digital painting[17] mainly refers to the process of creating paintings on computer software based on computers or graphic tables. Through pixel simulation, digital brushes in digital software (see the software in Digital painting) can imitate traditional painting paints and tools, such as oil, acrylic acid, pastel, charcoal, and airbrush. Users of the software can also customize the pixel size to achieve a unique visual effect (customized brushes).

Artificial intelligence art

Artists have used artificial intelligence to create artwork since at least the 1960s.[18] Since their design in 2014, some artists have created artwork using a generative adversarial network (GAN), which is a machine learning framework that allows two "algorithms" to compete with each other and iterate.[19][20] It is usually used to let the computer find the best solution by itself. It can be used to generate pictures that have visual effects similar to traditional fine art. The essential idea of image generators is that people can use text descriptions to let AI convert their text into visual picture content. Anyone can turn their language into a painting through a picture generator.[21] And some artists can use image generators to generate their paintings instead of drawing from scratch, and then they use the generated paintings as a basis to improve them and finally create new digital paintings. This greatly reduces the threshold of painting and challenges the traditional definition of painting art.

Generation Process

Generally, the user can set the input, and the input content includes detailed picture content that the user wants. For example, the content can be a scene's content, characters, weather, character relationships, specific items, etc. It can also include selecting a specific artist style, screen style, image pixel size, brightness, etc. Then picture generators will return several similar pictures[20] generated according to the input (generally, 4 pictures are given now). After receiving the results generated by picture generators, the user can select one picture as a result he wants or let the generator redraw and return to new pictures.

In addition, it is worth mentioning the whole process: it is also similar to the "generator" and "discriminator" modules[19] in GANs.

Awards and recognition

In both 1991 and 1992, Karl Sims won the Golden Nica award at Prix Ars Electronica for his 3D AI animated videos using artificial evolution.[22][23][24]

In 2009, Eric Millikin won the Pulitzer Prize along with several other awards for his artificial intelligence art that was critical of government corruption in Detroit and resulted in the city's mayor being sent to jail.[25][26][27]

In 2018 Christie's auction house in New York sold an artificial intelligence work, "Edmond de Bellamy" for US$432,500. It was created by a collective in Paris named "Obvious".[28]

In 2019, Stephanie Dinkins won the Creative Capital award for her creation of an evolving artificial intelligence based on the "interests and culture(s) of people of color."[29]

Also in 2019, Sougwen Chung won the Lumen Prize for her performances with a robotic arm that uses AI to attempt to draw in a manner similar to Chung.[30]

In 2022, an amateur artist using Midjourney won the first-place $300 prize in a digital art competition at the Colorado State Fair.[31][21]

Also in 2022, Refik Anadol created an artificial intelligence art installation at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, based on the museum's own collection.[32]

Art made for digital media

In contemporary art, the term digital art is used primarily to describe visual art that is made with digital tools, and also is highly computational, and explicitly engages with digital technologies. Art historian Christiane Paul writes that it "is highly problematic to classify all art that makes use of digital technologies somewhere in its production and dissemination process as digital art since it makes it almost impossible to arrive at any unifying statement about the art form.[33]

Digital installation art

Digital installation art constitutes a broad field of activity and incorporates many forms. Some resemble video installations, particularly large-scale works involving projections and live video capture. By using projection techniques that enhance an audience's impression of sensory envelopment, many digital installations attempt to create immersive environments. Others go even further and attempt to facilitate a complete immersion in virtual realms. This type of installation is generally site-specific, scalable, and without fixed dimensionality, meaning it can be reconfigured to accommodate different presentation spaces.[35]

Noah Wardrip-Fruin's "Screen" (2003) is an example of interactive digital installation art which makes use of a Cave Automatic Virtual Environment to create an interactive experience.[36] Scott Snibbe's "Boundary Functions" is an example of augmented reality digital installation art, which response to people who enter the installation by drawing lines between people, indicating their personal space.[34]

Internet art and net.art

Internet art is digital art that uses the specific characteristics of the internet and is exhibited on the internet.

Digital art and blockchain

Blockchain, and more specifically NFTs, are associated with digital art since the NFTs craze of 2020 and 2021. Digital art is a common use case for NFTs.[37] By minting a piece of digital art the owner of the NFT is proven to be the owner of the art piece.[38] While the technology received many critics and has many flaws related to plagiarism and fraud (due to its almost completely unregulated nature),[39] auction houses like Sotheby's, Christie's and various museums and galleries in the world started collaborations and partnerships with digital artists, selling NFTs associated with digital artworks (via NFT platforms) and showcasing those artworks (associated to the respective NFTs) both in virtual galleries and real life screens, monitors and TVs.[40][41][42]

Art theorists and historians

Notable art theorists and historians in this field include Oliver Grau, Jon Ippolito, Christiane Paul, Frank Popper, Jasia Reichardt, Mario Costa, Christine Buci-Glucksmann, Dominique Moulon, Robert C. Morgan, Roy Ascott, Catherine Perret, Margot Lovejoy, Edmond Couchot, Fred Forest and Edward A. Shanken.

Scholarship and archives

In addition to the creation of original art, research methods that utilize AI have been generated to quantitatively analyze digital art collections. This has been made possible due to large-scale digitization of artwork in the past few decades. Although the main goal of digitization was to allow for accessibility and exploration of these collections, the use of AI in analyzing them has brought about new research perspectives.[43]

Two computational methods, close reading and distant viewing, are the typical approaches used to analyze digitized art.[44] Close reading focuses on specific visual aspects of one piece. Some tasks performed by machines in close reading methods include computational artist authentication and analysis of brushstrokes or texture properties. In contrast, through distant viewing methods, the similarity across an entire collection for a specific feature can be statistically visualized. Common tasks relating to this method include automatic classification, object detection, multimodal tasks, knowledge discovery in art history, and computational aesthetics.[43] Whereas distant viewing includes the analysis of large collections, close reading involves one piece of artwork.

Whilst 2D and 3D digital art is beneficial as it allows the preservation of history that would otherwise have been destroyed by events like natural disasters and war, there is the issue of who should own these 3D scans – i.e., who should own the digital copyrights.[45]

Subtypes

- Art game

- ASCII art

- Chip art

- Computer art scene

- Computer music

- Crypto art

- Cyberarts

- Digital illustration

- Digital imaging

- Digital literature

- Digital painting

- Digital photography

- Digital poetry

- Digital sculpture

- Digital architecture

- Electronic music

- Evolutionary art

- Fractal art

- Generative art

- Generative music

- GIF art

- Immersion (virtual reality)

- Interactive art

- Internet art

- Motion graphics

- Music visualization

- Photo manipulation

- Pixel art

- Render art

- Software art

- Systems art

- Textures

Related organizations and conferences

See also

References

- {{Berry, D. M. and Dieter (2015) Postdigital Aesthetics: Art, Computation and Design, London: Palgrave. ISBN 978-1137437198

- Paul, Christiane (2016). "Introduction From Digital to Post‐Digital—Evolutions of an Art Form". In Paul, Christiane (ed.). A Companion to Digital Art. Malden, MA: Wiley. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-118-47520-1.

- Reichardt, Jasia (1974). "Twenty years of symbiosis between art and science". Art and Science. XXIV (1): 41–53.

- Christiane Paul (2006). Digital Art, pp. 7–8. Thames & Hudson.

- Lieser, Wolf. Digital Art. Langenscheidt: h.f. ullmann. 2009, pp. 13–15

- Grierson, Mick. "Creative Coding for Audiovisual Art: The CodeCircle Platform" (PDF).

- "Sketchpad | computer program | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- Pitxot, Antoni; Aguer, Montse (2022). "Cúpula". Guía - Teatro-Museo Dalí - Figueres (in Spanish). Barcelona: Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí - Triangle Books. p. 97. ISBN 978-84-8478-714-3.

A la derecha llama la atención el inmenso óleo fotográfico "Gala desnuda mirando al mar que a 18 metros aparece el presidente Lincoln" (1975), nueva muestra anticipadora de Dalí que representa ,en este caso, el primer ejemplo de utilización de imagen digitalizada en la pintura.

[On the right, attention is attracted by the immense photographic oil "Nude Gala Looking at the Sea that from 18 Meters Appears as President Lincoln (1975), new anticipating sample of Dalí that represents, in this case, the first example of the use of the digitized image in painting.] - Harmon, Leon D. (November 1973). "The Recognition of Faces". Scientific American. 229 (5): 70–82. Bibcode:1973SciAm.229e..70H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1173-70. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- 'Reimer, Jeremy (October 21, 2007). "A history of the Amiga, part 4: Enter Commodore". Arstechnica.com. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- YouTube. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07.

- Bessette, Juliette; Frederic Fol Leymarie; Glenn W. Smith (16 September 2019). "Trends and Anti-Trends in Techno-Art Scholarship: The Legacy of the Arts "Machine" Special Issues". Arts. 8 (3): 120. doi:10.3390/arts8030120.

- Smith, Glenn (31 May 2019). "An Interview with Frieder Nake". Arts. 8 (2): 69. doi:10.3390/arts8020069.

- Wands, Bruce (2006). Art of the Digital Age, pp. 15–16. Thames & Hudson.

- Foundation, Blender. "About". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- Lev Manovich (2001) The Language of New Media Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Jackson, Wallace (2015). Digital Painting Techniques Using Corel Painter 2016 (1st ed.). Berkeley, CA: Imprint: Apress. pp. intro. ISBN 9781484217368.

- McCorduck, Pamela (1991). AARONS's Code: Meta-Art. Artificial Intelligence, and the Work of Harold Cohen. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 210. ISBN 0-7167-2173-2.

- Andrej Karpathy; Pieter Abbeel; Greg Brockman; Peter Chen; Vicki Cheung; Rocky Duan; Ian Goodfellow; Durk Kingma; Jonathan Ho; Rein Houthooft; Tim Salimans; John Schulman; Ilya Sutskever; Wojciech Zaremba (2016-06-16). "Generative Models, OpenAI". OpenAI. Retrieved 2022-10-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ramesh, Aditya; Pavlov, Mikhail; Goh, Gabriel; Gray, Scott; Voss, Chelsea; Radford, Alec; Chen, Mark; Sutskever, Ilya (2021-02-26). "Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation". arXiv:2102.12092 [cs.CV].

- Roose, Kevin (2022-09-02). "An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren't Happy". The New York Times. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- "Golden Nicas". Ars Electronica Center. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- "Panspermia by Karl Sims, 1990". www.karlsims.com. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- "Liquid Selves by Karl Sims, 1992". www.karlsims.com. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- "Mayoral reporting: Free Press wins top honor". (April 1, 2009). Detroit Free Press, p. 5A.

- "Free Press wins its 9th Pulitzer; Reporting led to downfall of mayor". (April 21, 2009). Detroit Free Press, p.1A.

- "The 2009 Pulitzer Prize Winners: Local Reporting". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- Cohn, Gabe (2018-10-25). "AI Art at Christie's Sells for $432,500". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- "Not the Only One". Creative Capital. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- "Sougwen Chung". The Lumen Prize. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- "2022 Fine Arts Placings of the Colorado State Fair" (PDF).

- "Refik Anadol: Unsupervised | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- Christiane Paul, ed. (2016). A companion to digital art. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-118-47521-8. OCLC 925426732.

- "Boundary Functions"

- Paul, Christiane (2006). Digital Art, pp 71. Thames & Hudson.

- "screen - noah wardrip-fruin".

- Sestino, Andrea; Guido, Gianluigi; Peluso, Alessandro M. (2022). Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Examining the Impact on Consumers and Marketing Strategies. Palgrave. p. 26 f. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07203-1. ISBN 978-3-031-07202-4. S2CID 250238540.

- Kugler, Logan (2021). "Non-Fungible Tokens and the Future of Art". Communications of the ACM. 64 (9): 19–20. doi:10.1145/3474355. S2CID 237283169.

There is nothing stopping someone online from viewing, copying, and sharing a digital art file, but thanks to NFTs, they cannot fake possession of the art. NFTs make it possible to have exclusive ownership of digital art — something that was previously impossible.

Cf. Trautman, Lawrence J. (2022). "Virtual Art and Non-Fungible Tokens". Hofstra Law Review. 50 (361): 372 f. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3814087. S2CID 234830426. Trautman references Zittrain, Jonathan; Marks, Will (7 April 2021). "What Critics Don't Understand About NFTs. The complexity and arbitrariness of non-fungible tokens are a big part of their appeal". The Atlantic. Retrieved 11 January 2023.The buyer is not, however, acquiring anything that they alone can use. (...) an NFT buyer is not purchasing a work, but rather a publicly available token that links to a work. (...) The token itself is visible to all, as is the work to which it points, so anyone else can look at the work and download it. And most NFT transactions don't purport to convey copyright or other intellectual-property interests regarding the work in question (...) By these terms, many NFT purchases are akin to acquiring a piece of art that nevertheless remains in the gallery where it was sold, open all the time to members of the public, who may grab a free print of the work after their visit.

- "Does NFT Art Have A Place In The Museum In 2022?". jingculturecommerce.com. 6 January 2022.

- Trautman, Lawrence J. (2022). "Virtual Art and Non-Fungible Tokens". Hofstra Law Review. 50 (361): 371. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3814087. S2CID 234830426.

- "Natively Digital: A Curated NFT Sale". sothebys.com.

- "Beeple sold an NFT for $69 million". theverge.com. 11 March 2021.

- Cetinic, Eva; She, James (2022-02-16). "Understanding and Creating Art with AI: Review and Outlook". ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications. 18 (2): 66:1–66:22. arXiv:2102.09109. doi:10.1145/3475799. ISSN 1551-6857. S2CID 231951381.

- Lang, Sabine; Ommer, Bjorn (2018). "Reflecting on How Artworks Are Processed and Analyzed by Computer Vision: Supplementary Material". Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops – via Computer Vision Foundation.

- Sydell, Laura (21 May 2018). "3D Scans Help Preserve History, But Who Should Own Them? 2018". NPR. Archived from the original on 2022-01-18. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

External links

| Library resources about Digital art |

Media related to Digital art at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Digital art at Wikimedia Commons- Dreher, Thomas. "History of Computer Art"

- Zorich, Diane M. "Transitioning to a Digital World"