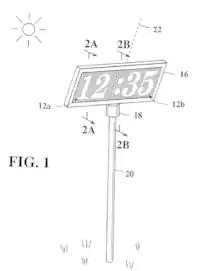

Digital sundial

A digital sundial is a clock that indicates the current time with numerals formed by the sunlight striking it. Like a classical sundial, the device contains no moving parts. It uses no electricity nor other manufactured sources of energy. The digital display changes as the sun advances in its daily course.

Technique

There are two basic types of digital sundials. One type uses optical waveguides, while the other is inspired by fractal geometry.

Optical fiber sundial

Sunlight enters into the device through a slit and moves as the sun advances. The sun's rays shine on ten linearly distributed sockets of optical waveguides that transport the light to a seven-segment display. Each socket fiber is connected to a few segments forming the digit corresponding to the position of the sun.[1]

Fractal sundial

The theoretical basis for the other construction comes from fractal geometry.[2] For the sake of simplicity, we describe a two-dimensional (planar) version. Let Lθ denote a straight line passing through the origin of a Cartesian coordinate system and making angle θ ∈ [0,π) with the x-axis. For any F ⊂ ℝ2 define projθ F to be the perpendicular projection of F on the line Lθ.

Theorem

Let Gθ ⊂ Lθ, θ ∈ [0,π) be a family of any sets such that Gθ is a measurable set in the plane. Then there exists a set F ⊂ ℝ2 such that

- Gθ ⊂ projθ F;

- the measure of the set projθ F \ Gθ is zero for almost all θ ∈ [0,π).

There exists a set with prescribed projections in almost all directions. This theorem can be generalized to three-dimensional space. For a non-trivial choice of the family Gθ, the set F described above is a fractal.

Application

Theoretically, it is possible to build a set of masks that produce shadows in the form of digits, such that the display changes as the sun moves. This is the fractal sundial.

The theorem was proved in 1987 by Kenneth Falconer. Four years later it was described in Scientific American by Ian Stewart.[3] The first prototype of a digital sundial was constructed in 1994; it writes the numbers with light instead of shadow, as Falconer proved. In 1998 a digital sundial was installed for the first time in a public place (Genk, Belgium).[4] There exist window and tabletop versions as well.[5] Julldozer in October 2015 published an open-source 3D printed model sundial.[6]

References

- US patent 4782472 (1988) belonged to HinesLab Inc. (USA) (US 4782472)

- Falconer, Kenneth (2003). Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. xxv. ISBN 0-470-84862-6.

- Ian Stewart, Scientific American, 1991, pages 104-106, Mathematical Recreations -- What in heaven is a digital sundial?.

- Sundial park in Genk, Belgium

- US and German patents belonged to Digital Sundials International (US 5590093, DE 4431817)

- Mojoptix 001: Digital Sundial