Dilatancy (granular material)

In soil mechanics, dilatancy is the volume change observed in granular materials when they are subjected to shear deformations.[1][2] This effect was first described scientifically by Osborne Reynolds in 1885/1886 [3][4] and is also known as Reynolds dilatancy. It was brought into the field of geotechnical engineering by Peter Walter Rowe.[5]

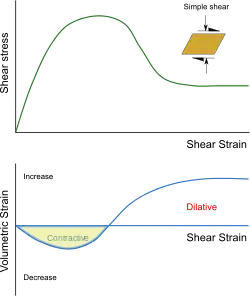

Unlike most other solid materials, the tendency of a compacted dense granular material is to dilate (expand in volume) as it is sheared. This occurs because the grains in a compacted state are interlocking and therefore do not have the freedom to move around one another. When stressed, a lever motion occurs between neighboring grains, which produces a bulk expansion of the material. On the other hand, when a granular material starts in a very loose state it may continuously compact instead of dilating under shear. A sample of a material is called dilative if its volume increases with increasing shear and contractive if the volume decreases with increasing shear.[6][7]

Dilatancy is a common feature of soils and sands. Its effect can be seen when the wet sand around the foot of a person walking on beach appears to dry up. The deformation caused by the foot expands the sand under it and the water in the sand moves to fill the new space between the grains.

Phenomenon

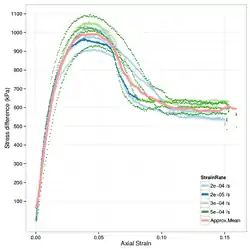

The phenomenon of dilatancy can be observed in a drained simple shear test on a sample of dense sand. In the initial stage of deformation, the volumetric strain decreases as the shear strain increases. But as the stress approaches its peak value, the volumetric strain starts to increase. After some more shear, the soil sample has a larger volume than when the test was started.

The amount of dilation depends strongly on the initial density of the soil. In general, the denser the soil, the greater the amount of volume expansion under shear. It has also been observed that the angle of internal friction decreases as the effective normal stress is decreased.[8]

The relationship between dilation and internal friction is typically illustrated by the sawtooth model of dilatancy where the angle of dilation is analogous to the angle made by the teeth to the horizontal. Such a model can be used to infer that the observed friction angle is equal to the dilation angle plus the friction angle for zero dilation.

Why is dilatancy important?

Because of dilatancy, the angle of friction increases as the confinement increases until it reaches a peak value. After the peak strength of the soil is mobilized the angle of friction abruptly decreases. As a result, geotechnical engineering of slopes, footings, tunnels, and piles in such soils have to consider the potential decrease in strength after the soil strength reaches this peak value.

Poorly / uniformly graded silt with trace sand to sandy that is non-plastic can be associated with challenges during construction, even when they are hard. These materials often appear to be granular because the silt is so coarse and thus may be described as dense to very dense. Vertical excavations below the water table in these soil types exhibit short term stability, similar to many dense sandy soil deposits, in part due to matric suction. However, as shearing of the soil occurs in the active wedge due to gravity forces, strength is lost and the rate of failure accelerates. This can be exacerbated by hydrostatic forces developing at the location(s) where water (drains to and) collects in tension cracks in or near the back of the active wedge. Generally retrogressive spalling manifests, often accompanied by piping / internal erosion. The use of appropriate filters is critical to managing these materials; a preferred filter might be a #4 sized clear gravel / coarse-grained sand as a commercial aggregate which is generally readily available. Some non- woven filter fabrics are also suitable. As with all filters, D15 and D50 compatibility criteria should be checked.

Dilatancy cut-off

After extensive shearing, dilating materials arrive in a state of critical density where dilatancy has come to an end. This phenomenon of soil behaviour can be included in the Hardening Soil model by means of a dilatancy cut-off. In order to specify this behaviour, the initial void ratio, , and the maximum void ratio, , of the material must be entered as general parameters. As soon as the volume change results in a state of maximum void, the mobilised dilatancy angle, , is automatically set back to zero.[9]

See also

References

- Nedderman, R.M. (2005). Statics and kinematics of granular materials (Digitally printed 1st pbk. version. ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01907-9.

- Pouliquen, Bruno Andreotti, Yoël Forterre, Olivier (2013). Granular media : between fluid and solid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107034792.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Reynolds, Osborne (December 1885). "LVII. On the dilatancy of media composed of rigid particles in contact, with experimental illustrations". Philosophical Magazine. Series 5. 20 (127): 469–481. doi:10.1080/14786448508627791.

- Reynolds, O., "Experiments showing dilatancy, a property of granular material, possibly connected with gravitation," Proc. Royal Institution of Great Britain, Read, February 12, 1886.

- Rowe, P. W., "The stress-dilatancy relation for static equilibrium of an assembly of particles in contact," Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 1962.

- Casagrande, A., Hirschfeld, R. C., & Poulos, S. J. (1964). Fourth Report: Investigation of Stress-Deformation and Strength Characteristics of Compacted Clays. HARVARD UNIV CAMBRIDGE MA SOIL MECHANICS LAB.

- Poulos, S. J. (1971). The stress-strain curves of soils. Geotechnical Engineers Incorporated. Chicago.

- Houlsby, G. T. How the dilatancy of soils affects their behaviour. University of Oxford, Department of Engineering Science, 1991.http://www.eng.ox.ac.uk/civil/publications/reports-1/ouel_1888_91.pdf

- PLAXIS 2D CE V20.02: 3 - Material Models Manual.pdf page 78