Sidney Dillon Ripley

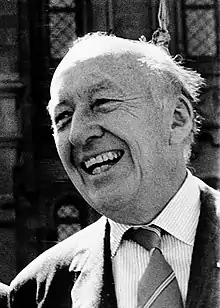

Sidney Dillon Ripley II (September 20, 1913 – March 12, 2001) was an American ornithologist and wildlife conservationist. He served as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for 20 years, from 1964 to 1984, leading the institution through its period of greatest growth and expansion. For his leadership at the Smithsonian, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Ronald Reagan in 1985.[3]

Sidney Dillon Ripley | |

|---|---|

Ripley in 1984 | |

| 8th Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution | |

| In office 1964–1984 | |

| Preceded by | Leonard Carmichael |

| Succeeded by | Robert McCormick Adams |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Sidney Dillon Ripley II September 20, 1913 New York City, New York |

| Died | March 12, 2001 (aged 87) Washington, D.C. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Yale University (BA) Harvard University (PhD) |

| Known for | Ornithology |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (1985)[1] Padma Bhushan (1986)[2] |

Biography

Early life

Ripley was born in New York City, after a brother, Louis, was born in 1906 in Litchfield, Connecticut.[4] His mother was Constance Baillie Rose of Scottish descent while his father was Louis Arthur Dillon Ripley, a wealthy real estate agent who drove around in an 1898 Renault Voiturette. Both his paternal grandparents, Julia and Josiah Dwight Ripley, died before he was born but he was connected to them through Cora Dillon Wyckoff. Great Aunt Cora and her husband, Dr. Peter Wyckoff, often hosted young Ripley at their Park Avenue apartment. Cora's and Julia's father (his great-grandfather) and partial namesake was Sidney Dillon, twice President of the Union Pacific Railroad.[5] and his uncle was Sidney Dillon Ripley I. Both Gilded Age tycoons.

Ripley's early education was at the Montessori Kindergarten School on Madison Avenue. As a young boy, he traveled widely including to British Columbia where his mother's relatives lived. In April 1918, his mother, who had separated from his father, moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts. In 1919 the family moved again to Boston, where he studied in a school called Rivers. At the age of ten, he traveled again with his mother across Europe. In 1924 Ripley went to a boarding school called Fay in Southborough, Massachusetts.

In 1926 he followed in Louis' footsteps, attending St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire. In 1936, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from Yale University. While at Yale he briefly considered a more traditional career path after a conversation with his brother. "Louis told me we ought to have a lawyer in the family," he has said, "but I really hated the idea, and in the summer of 1936, after graduating from college, I resolved to abandon all thoughts of a prosperous and worthy future and devote myself to birds, the subject I was overpoweringly interested in."[6]

Travel and education

.jpg.webp)

A friend of the Ripleys, John, whose father founded the Young Men's Christian Association, and Celestine Mott were planning a visit to India to set up a YMCA hostel in India. This led to a visit to India at age 13, along with his sister. They stayed at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay and then went to Kashmir and included a walking tour into Ladakh and western Tibet. In Kashmir, they flew falcons with Colonel Biddulph. They also visited Calcutta and Nagpur. One of Ripley's brothers shot a tiger at a shoot hosted by a Maharaja.[7] This led to his lifelong interest in the birds of India.[3] He returned to St Paul's to complete his studies. It was suggested to him that Yale would be the best for him. Ripley received a training in making specimens from Frank Chapman and even had tea once as a sophomore Erwin Stresemann.[8] He decided that birds were more interesting than law and after graduating from Yale in 1936 he was advised by Ernst Mayr that "the most important thing you can do is get a sound and broad biological training." He then enrolled at Columbia University. and he began studying zoology at Columbia University. As a part of his study, Ripley participated in the Denison-Crockett Expedition to New Guinea in 1937-1938 and the Vanderbilt Expedition to Sumatra in 1939.[9] He later obtained a PhD in Zoology from Harvard University in 1943.

War service and academic work

During World War II, he served under William J. Donovan ("Coordinator of Information") in the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency. In the early days Ripley acted as liaison with the British Security Coordination led by Sir William Stephenson at the Rockefeller Center. He later was in charge of American intelligence services in Southeast Asia.[3] Others who joined the OSS early included Ripley's Yale friends Sherman Kent and Wilmarth S. Lewis.[10] Ripley held a high regard for his OSS colleagues and considered it unfair on the part of some to decry those who were socially inclined leading to some calling the organization as "Oh So Social".[11] Ripley trained many Indonesian spies, all of whom were killed during the war.[12] He was posted briefly to Australia with the identity of a lieutenant colonel in case he was captured. He was to go through England, Egypt, China and then on to India and Ceylon. He then worked with Detachment 404 in Bangkok, working to recover Allied airmen who had been captured in the region with the help of friendly Thais who worked to keep them under cover from the Japanese forces. After this period he moved to Sri Lanka and never got to Australia as originally planned.[13] He worked with and "cultivated" Lord Mountbatten throughout this period. The two often met at dinners and parties both in New Delhi and at Trincomalee. On one occasion, Ripley noticed a green woodpecker and went off to shoot it while dressed only in a towel. The specimen label reads "Shot at cocktail party... towel fell off."[14] It was in Kandy, Sri Lanka that he met his future wife Mary Livingston and her roommate Julia Child (then Julia McWilliams) both working with the OSS. The anthropologist Gregory Bateson was also here and he would introduce Julia to Paul Child, her future husband.[15] An article in the August 26, 1950 New Yorker said that Ripley reversed the usual pattern, where spies posed as ornithologists in order to gain access to sensitive areas, and instead used his position as an intelligence officer to go birding in restricted areas.[16][17] The government of Thailand awarded him the Order of the White Elephant, a national award for his support of the Thai underground during the war.[12] In 1947, Ripley entered Nepal pretending to be a close confidante of Jawaharlal Nehru and the Nepal government, eager to maintain diplomatic ties with its newly independent neighbour, allowed him and Edward Migdalski to collect bird specimens. Nehru came to hear of this from an article in The New Yorker and was furious, leading to a difficult time for his collaborator and coauthor, Salim Ali. Salim Ali came to hear of Nehru's displeasure through Horace Alexander and the matter was forgiven after some effort.[18] The OSS past however led to a growing suspicion that American scientists working in India were CIA agents. David Challinor, a former Smithsonian administrator, noted that there were many CIA agents in India, with some posing as scientists. He noted that the Smithsonian sent a scholar to India for anthropological research who unknown to them was interviewing Tibetan refugees from Chinese-occupied Tibet but went on to say that there was no evidence that Ripley worked for the CIA after he left the OSS in 1945.[12]

He joined the American Ornithologists' Union in 1938, became an Elective Member in 1942, and a fellow in 1951. After the war he taught at Yale and was a Fulbright fellow in 1950 and a Guggenheim fellow in 1954.[3] At Yale, one of the key scientific influences on Ripley was the ecologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson, who had led the Yale expedition to India in 1932.[19] Ripley became a full professor and director of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. Ripley served for many years on the board of the World Wildlife Fund in the U.S., and was the third president of the International Council for Bird Preservation (ICBP, now BirdLife International).

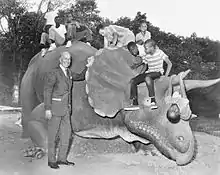

Smithsonian Institution

He served as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution from 1964 to 1984. He set out to reinvigorate and expand the Smithsonian, building new museums, including the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, now the Anacostia Community Museum, Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Renwick Gallery, National Air and Space Museum, National Museum of African Art, Enid A. Haupt Garden, the underground quadrangle complex known as the S. Dillon Ripley Center, and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.[9]

In 1967, he helped found the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, and in 1970, he helped found Smithsonian magazine. He believed that 75% to 80% of then-living animal species would become extinct in the next 25 years.[20]

In 1985 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award of the United States. He was awarded honorary degrees from 15 colleges and universities, including Brown, Yale, Johns Hopkins, Harvard, and Cambridge. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[21][22][23]

Ripley successfully defended the National Museum of Natural History against a lawsuit that objected to the Dynamics of Evolution exhibit.[9]

Legacy

Ripley had intended to produce a definitive guide to the birds of South Asia, but became too ill to play an active part in its realisation. However, the eventual authors, his assistant, Pamela C. Rasmussen, and artist John C. Anderton, named the final two-volume guide as Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide in his honor.

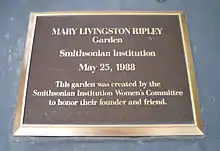

The Smithsonian's underground complex on the National Mall, the S. Dillon Ripley Center, is named in his honor. A garden between the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden and the Arts and Industries Building was dedicated in 1988 to his wife, Mary Livingston Ripley.

The first-ever full-length biography of Ripley, The Lives of Dillon Ripley: Natural Scientist, Wartime Spy, and Pioneering Leader of the Smithsonian Institution by Roger D. Stone, was published in 2017.[24]

The Livingston Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy, a non-profit zoo dedicated to breeding endangered waterfowl, is located on 150-acres of the Ripley estate in Litchfield, Connecticut. The zoo's history began in the 1920s when Ripley began keeping and breeding waterfowl as a teenager, and he is credited with the first captive breedings of Red-breasted goose, Nene, Emperor goose, and Laysan Teal as well as the first US captive breedings of New Zealand scaup, Greenland Mallard (A. p. conboschas), and Philippine duck. In 1985, Dillon and his wife, Mary Livingston Ripley, donated the chunk of their estate that is today the zoo to the non-profit organization that continues to operate it. Today the zoo houses over 60 species of birds, totaling over 400 individual animals. Ripley's three daughters continue to serve on the zoo's board of directors.[25]

Selected writings

- The Land and Wildlife of Tropical Asia (1964; Series: LIFE Nature Library)

- Rails of the World: A Monograph of the Family Rallidae (1977)

- The paradox of the human condition : a scientific and philosophic exposition of the environmental and ecological problems that face humanity (1975)

- Birds of Bhutan, with Salim Ali and Biswamoy Biswas

- Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan, with Salim Ali (10 volumes)

- The Sacred Grove: Essays on Museums (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1969)

Notes

- "Announcement of the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, April 8, 1985". The American Presidency Project. University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- "Padma Awards" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- Molotsky, Irvin (13 March 2001). "S. Dillon Ripley Dies at 87; Led the Smithsonian Institution During Its Greatest Growth". The New York Times. p. 9.

- "Louis R. Ripley". The New York Times. Mar 10, 1983. Retrieved Aug 12, 2020.

- Stone (2017):1-5.

- Hellman, Geoffrey T. "Curator Getting Around". The New Yorker. Retrieved Aug 12, 2020.

- Stone (2017):10-15.

- Stone (2017):25.

- "S. Dillon Ripley, 1913-2001". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Apr 14, 2011. Retrieved Aug 12, 2020.

- Stone (2017):46.

- Stone (2017):48-49.

- Lewis, Michael (2002). "Scientists or Spies? Ecology in a Climate of Cold War Suspicion". Economic and Political Weekly. 37.

- Stone (2017):56-58.

- Stone (2017):60.

- Stone (2017):58.

- Hellman, Geoffrey T. (1950) Curator Getting Around. The New Yorker. August 26, 1950.

- Lewis, Michael (2003) Inventing Global Ecology: Tracking the Biodiversity Ideal in India, 1945-1997. Orient Blackswan. p. 117.

- Stone (2017):75-76.

- Stone (2017):66-68.

- R Bailey (2000) Earth day then and now, Reason 32(1), 18-28

- "S. Dillon Ripley". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- "Sidney Dillon Ripley". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- Stone, Roger D. (2017-06-06). The Lives of Dillon Ripley: Natural Scientist, Wartime Spy, and Pioneering Leader of the Smithsonian Institution. University Press of New England. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1xx9jw6. ISBN 978-1-5126-0061-2.

- "LRWC - history". Archived from the original on 2010-05-09.

References

- Stone, Roger D. (2017) The Lives of Dillon Ripley. ForeEdge.

- Hussain, S.A. (2002). "Sidney Dillon Ripley II 1913–2001". Ibis. 144 (3): 550. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2002.00090_1.x.

External links

- Biography from the Smithsonian Institution Archives

- Biography and obituary in Smithsonian magazine

- Obituary in The New York Times

- Livingston Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy