Diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae.[1] Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks, the lethality rate approaches 10%.[2] Signs and symptoms may vary from mild to severe,[2] and usually start two to five days after exposure.[1] Symptoms often develop gradually, beginning with a sore throat and fever.[2] In severe cases, a grey or white patch develops in the throat,[1][2] which can block the airway, and create a barking cough similar to what is observed in croup.[2] The neck may also swell in part due to the enlargement of the facial lymph nodes.[1] Diphtheria can also involve the skin, eyes, or genitals, and can cause[1][2] complications, including myocarditis (which in itself can result in an abnormal heart rate), inflammation of nerves (which can result in paralysis), kidney problems, and bleeding problems due to low levels of platelets.[1]

| Diphtheria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diphtheria can cause a swollen neck, sometimes referred to as a bull neck.[1] | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Sore throat, fever, barking cough[2] |

| Complications | Myocarditis, Peripheral neuropathy, Proteinuria |

| Usual onset | 2–5 days post-exposure[1] |

| Causes | Corynebacterium diphtheriae (spread by direct contact and through the air)[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Examination of throat, culture[2] |

| Prevention | Diphtheria vaccine[1] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, tracheostomy[1] |

| Prognosis | 5–10% risk of death |

| Frequency | 4,500 (reported 2015)[3] |

| Deaths | 2,100 (2015)[4] |

Diphtheria is usually spread between people by direct contact, through the air, or through contact with contaminated objects.[1][5] Asymptomatic transmission and chronic infection are also possible.[1] Different strains of C. diphtheriae are the main cause in the variability of lethality,[1] as the lethality and symptoms themselves are caused by the exotoxin produced by the bacteria.[2] Diagnosis can often be made based on the appearance of the throat with confirmation by microbiological culture.[2] Previous infection may not protect against infection.[2]

A diphtheria vaccine is effective for prevention, and is available in a number of formulations.[1] Three or four doses, given along with tetanus vaccine and pertussis vaccine, are recommended during childhood.[1] Further doses of the diphtheria–tetanus vaccine are recommended every ten years.[1] Protection can be verified by measuring the antitoxin level in the blood.[1] Diphtheria can be prevented in those exposed, as well as treated with the antibiotics erythromycin or benzylpenicillin.[1] A tracheotomy is sometimes needed to open the airway in severe cases.[2]

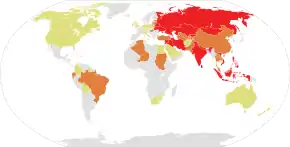

In 2015, 4,500 cases were officially reported worldwide, down from nearly 100,000 in 1980.[3] About a million cases a year are believed to have occurred before the 1980s.[2] Diphtheria currently occurs most often in sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Indonesia.[2][6] In 2015, it resulted in 2,100 deaths, down from 8,000 deaths in 1990.[4][7] In areas where it is still common, children are most affected.[2] It is rare in the developed world due to widespread vaccination, but can re-emerge if vaccination rates decrease.[2][8] In the United States, 57 cases were reported between 1980 and 2004.[1] Death occurs in 5% to 10% of those diagnosed.[1] The disease was first described in the 5th century BC by Hippocrates.[1] The bacterium was identified in 1882 by Edwin Klebs.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of diphtheria usually begin two to seven days after infection. They include fever of 38 °C (100.4 °F) or above; chills; fatigue; bluish skin coloration (cyanosis); sore throat; hoarseness; cough; headache; difficulty swallowing; painful swallowing; difficulty breathing; rapid breathing; foul-smelling and bloodstained nasal discharge; and lymphadenopathy.[9][10] Within two to three days, diphtheria may destroy healthy tissues in the respiratory system. The dead tissue forms a thick, gray coating that can build up in the throat or nose. This thick gray coating is called a "pseudomembrane." It can cover tissues in the nose, tonsils, voice box, and throat, making it very hard to breathe and swallow.[11] Symptoms can also include cardiac arrhythmias, myocarditis, and cranial and peripheral nerve palsies.[12]

Diphtheritic croup

Laryngeal diphtheria can lead to a characteristic swollen neck and throat, or "bull neck." The swollen throat is often accompanied by a serious respiratory condition, characterized by a brassy or "barking" cough, stridor, hoarseness, and difficulty breathing; and historically referred to variously as "diphtheritic croup,"[13] "true croup,"[14][15] or sometimes simply as "croup."[16] Diphtheritic croup is extremely rare in countries where diphtheria vaccination is customary. As a result, the term "croup" nowadays most often refers to an unrelated viral illness that produces similar but milder respiratory symptoms.[17]

Transmission

Human-to-human transmission of diphtheria typically occurs through the air when an infected individual coughs or sneezes. Breathing in particles released from the infected individual leads to infection.[18] Contact with any lesions on the skin can also lead to transmission of diphtheria, but this is uncommon.[19] Indirect infections can occur, as well. If an infected individual touches a surface or object, the bacteria can be left behind and remain viable. Also, some evidence indicates diphtheria has the potential to be zoonotic, but this has yet to be confirmed. Corynebacterium ulcerans has been found in some animals, which would suggest zoonotic potential.[20]

Mechanism

Diphtheria toxin (DT) is produced only by C. diphtheriae infected with a certain type of bacteriophage.[21][22] Toxinogenicity is determined by phage conversion (also called lysogenic conversion); i.e., the ability of the bacterium to make DT changes as a consequence of infection by a particular phage. DT is encoded by the tox gene. Strains of corynephage are either tox+ (e.g., corynephage β) or tox− (e.g., corynephage γ). The tox gene becomes integrated into the bacterial genome.[23] The chromosome of C. diphtheriae has two different but functionally equivalent bacterial attachment sites (attB) for integration of β prophage into the chromosome.

Diphtheria toxin precursor is a protein of molecular weight 60 kDa. Certain proteases, such as trypsin, selectively cleave DT to generate two peptide chains, amino-terminal fragment A (DT-A) and carboxyl-terminal fragment B (DT-B), which are held together by a disulfide bond.[23] DT-B is a recognition subunit that gains entry of DT into the host cell by binding to the EGF-like domain of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor on the cell surface. This signals the cell to internalize the toxin within an endosome via receptor-mediated endocytosis. Inside the endosome, DT is split by a trypsin-like protease into DT-A and DT-B. The acidity of the endosome causes DT-B to create pores in the endosome membrane, thereby catalysing the release of DT-A into the cytoplasm.[23]

Fragment A inhibits the synthesis of new proteins in the affected cell by catalyzing ADP-ribosylation of elongation factor EF-2—a protein that is essential to the translation step of protein synthesis. This ADP-ribosylation involves the transfer of an ADP-ribose from NAD+ to a diphthamide (a modified histidine) residue within the EF-2 protein. Since EF-2 is needed for the moving of tRNA from the A-site to the P-site of the ribosome during protein translation, ADP-ribosylation of EF-2 prevents protein synthesis.[24]

ADP-ribosylation of EF-2 is reversed by giving high doses of nicotinamide (a form of vitamin B3), since this is one of the reaction's end products, and high amounts drive the reaction in the opposite direction.[25]

Diagnosis

The current clinical case definition of diphtheria used by the United States' Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is based on both laboratory and clinical criteria.

Laboratory criteria

- Isolation of C. diphtheriae from a Gram stain or throat culture from a clinical specimen.[10]

- Histopathologic diagnosis of diphtheria by Albert's stain.

Toxin demonstration

- In vivo tests (guinea pig inoculation): Subcutaneous and intracutaneous tests.

- In vitro test: Elek's gel precipitation test, detection of tox gene by PCR, ELISA, ICA.

Clinical criteria

- Upper respiratory tract illness with sore throat.

- Low-grade fever (above 39 °C (102 °F) is rare).

- An adherent, dense, grey pseudomembrane covering the posterior aspect of the pharynx; in severe cases, it can extend to cover the entire tracheobronchial tree.

Case classification

- Probable: a clinically compatible case that is not laboratory-confirmed, and is not epidemiologically linked to a laboratory-confirmed case.

- Confirmed: a clinically compatible case that is either laboratory-confirmed or epidemiologically linked to a laboratory-confirmed case.

Empirical treatment should generally be started in a patient in whom suspicion of diphtheria is high.

Prevention

Vaccination against diphtheria is commonly done in infants, and delivered as a combination vaccine, such as a DPT vaccine (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus). Pentavalent vaccines, which vaccinate against diphtheria and four other childhood diseases simultaneously, are frequently used in disease prevention programs in developing countries by organizations such as UNICEF.[26]

Treatment

The disease may remain manageable, but in more severe cases, lymph nodes in the neck may swell, and breathing and swallowing are more difficult. People in this stage should seek immediate medical attention, as obstruction in the throat may require intubation or a tracheotomy. Abnormal cardiac rhythms can occur early in the course of the illness or weeks later, and can lead to heart failure. Diphtheria can also cause paralysis in the eye, neck, throat, or respiratory muscles. Patients with severe cases are put in a hospital intensive care unit, and given diphtheria antitoxin (consisting of antibodies isolated from the serum of horses that have been challenged with diphtheria toxin).[27] Since antitoxin does not neutralize toxin that is already bound to tissues, delaying its administration increases risk of death. Therefore, the decision to administer diphtheria antitoxin is based on clinical diagnosis, and should not await laboratory confirmation.[28]

Antibiotics have not been demonstrated to affect healing of local infection in diphtheria patients treated with antitoxin. Antibiotics are used in patients or carriers to eradicate C. diphtheriae, and prevent its transmission to others. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends[29] either:

- Metronidazole

- Erythromycin is given (orally or by injection) for 14 days (40 mg/kg per day with a maximum of 2 g/d), or

- Procaine penicillin G is given intramuscularly for 14 days (300,000 U/d for patients weighing <10 kg, and 600,000 U/d for those weighing >10 kg); patients with allergies to penicillin G or erythromycin can use rifampin or clindamycin.

In cases that progress beyond a throat infection, diphtheria toxin spreads through the blood, and can lead to potentially life-threatening complications that affect other organs, such as the heart and kidneys. Damage to the heart caused by the toxin affects the heart's ability to pump blood, or the kidneys' ability to clear wastes. It can also cause nerve damage, eventually leading to paralysis. About 40% to 50% of those left untreated can die.[30]

Epidemiology

Diphtheria is fatal in between 5% and 10% of cases. In children under five years and adults over 40 years, the fatality rate may be as much as 20%.[28] In 2013, it resulted in 3,300 deaths, down from 8,000 deaths in 1990.[7] Better standards of living, mass immunization, improved diagnosis, prompt treatment, and more effective health care have led to a decrease in cases worldwide.[31]

History

In 1613, Spain experienced an epidemic of diphtheria, referred to as El Año de los Garrotillos (The Year of Strangulations).[31]

In 1705, the Mariana Islands experienced an epidemic of diphtheria and typhus simultaneously, reducing the population to about 5,000 people.[32]

In 1735, a diphtheria epidemic swept through New England.[33]

Before 1826, diphtheria was known by different names across the world. In England, it was known as “Boulogne sore throat,” as the illness had spread from France. In 1826, Pierre Bretonneau gave the disease the name diphthérite (from Greek διφθέρα, diphthera 'leather'), describing the appearance of pseudomembrane in the throat.[34][35]

In 1856, Victor Fourgeaud described an epidemic of diphtheria in California.[36]

In 1878, Princess Alice (Queen Victoria's second daughter) and her family became infected with diphtheria; Princess Alice and her four-year-old daughter, Princess Marie, both died.[37]

In 1883, Edwin Klebs identified the bacterium causing diphtheria,[38] and named it Klebs–Loeffler bacterium. The club shape of this bacterium helped Edwin to differentiate it from other bacteria. Over time, it has been called Microsporon diphtheriticum, Bacillus diphtheriae, and Mycobacterium diphtheriae. Current nomenclature is Corynebacterium diphtheriae.

In 1884, German bacteriologist Friedrich Loeffler became the first person to cultivate C. diphtheriae.[39] He used Koch's postulates to prove association between C. diphtheriae and diphtheria. He also showed that the bacillus produces an exotoxin.

In 1885, Joseph P. O'Dwyer introduced the O'Dwyer tube for laryngeal intubation in patients with an obstructed larynx. It soon replaced tracheostomy as the emergency diphtheric intubation method.[40]

In 1888, Emile Roux and Alexandre Yersin showed that a substance produced by C. diphtheriae caused symptoms of diphtheria in animals.[41][42]

In 1890, Shibasaburō Kitasato and Emil von Behring immunized guinea pigs with heat-treated diphtheria toxin.[43] They also immunized goats and horses in the same way, and showed that an "antitoxin" made from serum of immunized animals could cure the disease in non-immunized animals. Behring used this antitoxin (now known to consist of antibodies that neutralize the toxin produced by C. diphtheriae) for human trials in 1891, but they were unsuccessful. Successful treatment of human patients with horse-derived antitoxin began in 1894, after production and quantification of antitoxin had been optimized.[44][27] In 1901, Von Behring won the first Nobel Prize in medicine for his work on diphtheria.[45]

In 1895, H. K. Mulford Company of Philadelphia started production and testing of diphtheria antitoxin in the United States.[46] Park and Biggs described the method for producing serum from horses for use in diphtheria treatment.

In 1897, Paul Ehrlich developed a standardized unit of measure for diphtheria antitoxin. This was the first ever standardization of a biological product, and played an important role in future developmental work on sera and vaccines.[47]

In 1901, 10 of 11 inoculated St. Louis children died from contaminated diphtheria antitoxin. The horse from which the antitoxin was derived died of tetanus. This incident, coupled with a tetanus outbreak in Camden, New Jersey,[48] played an important part in initiating federal regulation of biologic products.[49]

On 7 January 1904, Ruth Cleveland died of diphtheria at the age of 12 years in Princeton, New Jersey. Ruth was the eldest daughter of former President Grover Cleveland and the former First Lady, Frances Folsom.

In 1905, Franklin Royer, from Philadelphia's Municipal Hospital, published a paper urging timely treatment for diphtheria and adequate doses of antitoxin.[50] In 1906, Clemens Pirquet and Béla Schick described serum sickness in children receiving large quantities of horse-derived antitoxin.[51]

Between 1910 and 1911, Béla Schick developed the Schick test to detect pre-existing immunity to diphtheria in an exposed person. Only those who had not been exposed to diphtheria were vaccinated. A massive, five-year campaign was coordinated by Dr. Schick. As a part of the campaign, 85 million pieces of literature were distributed by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, with an appeal to parents to "Save your child from diphtheria." A vaccine was developed in the next decade, and deaths began declining significantly in 1924.[52]

In 1919, in Dallas, Texas, 10 children were killed and 60 others made seriously ill by toxic antitoxin which had passed the tests of the New York State Health Department. The manufacturer of the antitoxin, the Mulford Company of Philadelphia, paid damages in every case.[53]

During the 1920s, an annual estimate of 100,000 to 200,000 diphtheria cases and 13,000 to 15,000 deaths occurred in the United States.[28] Children represented a large majority of these cases and fatalities. One of the most infamous outbreaks of diphtheria occurred in 1925, in Nome, Alaska; the "Great Race of Mercy" to deliver diphtheria antitoxin is now celebrated by the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race.[54]

In 1926, Alexander Thomas Glenny increased the effectiveness of diphtheria toxoid (a modified version of the toxin used for vaccination) by treating it with aluminum salts.[55] Vaccination with toxoid was not widely used until the early 1930s.[56] In 1939, Dr. Nora Wattie, who was the Principal Medical Officer (Maternity and Child Welfare) of Glasgow between 1934– 1964,[57] introduced immunisation clinics across Glasgow, and promoted mother and child health education, resulting in virtual eradication of the infection in the city.[58]

Widespread vaccination pushed cases in the United States down from 4.4 per 100,000 inhabitants in 1932 to 2.0 in 1937. In Nazi Germany, where authorities preferred treatment and isolation over vaccination (until about 1939–1941), cases rose over the same period from 6.1 to 9.6 per 100,000 inhabitants.[59]

Between June 1942 and February 1943, 714 cases of diphtheria were recorded at Sham Shui Po Barracks, resulting in 112 deaths because the Imperial Japanese Army did not release supplies of anti-diphtheria serum.[60]

In 1943, diphtheria outbreaks accompanied war and disruption in Europe. The 1 million cases in Europe resulted in 50,000 deaths.

During 1948 in Kyoto, 68 of 606 children died after diphtheria immunization due to improper manufacture of aluminum phosphate toxoid.[61]

In 1974, the World Health Organization included DPT vaccine in their Expanded Programme on Immunization for developing countries.[62][63]

In 1975, an outbreak of cutaneous diphtheria in Seattle, Washington was reported.[64]

After the breakup of the former Soviet Union in 1991, vaccination rates in its constituent countries fell so low that an explosion of diphtheria cases occurred. In 1991, 2,000 cases of diphtheria occurred in the USSR. Between 1991 and 1998, as many as 200,000 cases were reported in the Commonwealth of Independent States, and resulted in 5,000 deaths.[31] In 1994, the Russian Federation had 39,703 diphtheria cases. By contrast, in 1990, only 1,211 cases were reported.[65]

In early May 2010, a case of diphtheria was diagnosed in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, after the devastating 2010 Haiti earthquake. The 15-year-old male patient died while workers searched for antitoxin.[66]

In 2013, three children died of diphtheria in Hyderabad, India.[67]

In early June 2015, a case of diphtheria was diagnosed at Vall d'Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona, Spain. The six-year-old child who died of the illness had not been previously vaccinated due to parental opposition to vaccination.[68] It was the first case of diphtheria in the country since 1986, as reported by the Spanish daily newspaper El Mundo,[69] or from 1998, as reported by the WHO.[70]

In March 2016, a three-year-old girl died of diphtheria in the University Hospital of Antwerp, Belgium.[71]

In June 2016, a three-year-old, five-year-old, and seven-year-old girl died of diphtheria in Kedah, Malacca, and Sabah, Malaysia.[72]

In January 2017, more than 300 cases were recorded in Venezuela.[73][74]

In 2017, outbreaks occurred in a Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh, and amongst children unvaccinated due to the Yemeni Civil War.[75]

In November and December 2017, an outbreak of diphtheria occurred in Indonesia, with more than 600 cases found and 38 fatalities.[76]

In November 2019, two cases of diphtheria occurred in the Lothian area of Scotland.[77] Additionally, in November 2019, an unvaccinated 8-year-old boy died of diphtheria in Athens, Greece.[78]

In July 2022, two cases of diphtheria occurred in northern New South Wales, Australia.[79]

In October 2022, there was an outbreak of diphtheria at the former Manston airfield, a former Ministry of Defence (MoD) site in Kent, England, which had been converted to an asylum seeker processing centre. The capacity of the processing centre was 1,000 people, although about 3,000 were living at the site, with some accommodated in tents. The Home Office, the government department responsible for asylum seekers, refused to confirm the number of cases.[80]

References

- Atkinson, William (May 2012). Diphtheria Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12 ed.). Public Health Foundation. pp. 215–230. ISBN 9780983263135. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016.

- "Diphtheria vaccine" (PDF). Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 81 (3): 24–32. 20 January 2006. PMID 16671240. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2015.

- "Diphtheria". who.int. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- Kowalski, Wladyslaw (2012). Hospital airborne infection control. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 54. ISBN 9781439821961. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (8 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014. p. 2372. ISBN 9780323263733. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- Al, A. E. Paniz-Mondolfi et (2019). "Resurgence of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in Venezuela as a Regional Public Health Threat in the Americas – Volume 25, Number 4 – April 2019 – Emerging Infectious Diseases journal – CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 25 (4): 625–632. doi:10.3201/eid2504.181305. PMC 6433037. PMID 30698523.

- "Diphtheria—Symptoms—NHS Choices". Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- "Updating PubMed Health". PubMed Health. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- "Diphtheria Symptoms". www.cdc.gov. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "Diphtheria". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 4 August 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Loving, Starling (5 October 1895). "Something concerning the diagnosis and treatment of false croup". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. XXV (14): 567–573. doi:10.1001/jama.1895.02430400011001d. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- Cormack, John Rose (8 May 1875). "Meaning of the Terms Diphtheria, Croup, and Faux Croup". British Medical Journal. 1 (749): 606. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.749.606. PMC 2297755. PMID 20747853.

- Bennett, James Risdon (8 May 1875). "True and False Croup". British Medical Journal. 1 (749): 606–607. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.749.606-a. PMC 2297754. PMID 20747854.

- Beard, George Miller (1875). Our Home Physician: A New and Popular Guide to the Art of Preserving Health and Treating Disease. New York: E. B. Treat. pp. 560–564. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- Vanderpool, Patricia (December 2012). "Recognizing croup and stridor in children". American Nurse Today. 7 (12). Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- Diphtheria Causes and Transmission Archived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2016).

- Youwang Y.; Jianming D.; Yong X.; Pong Z. (1992). "Epidemiological features of an outbreak of diphtheria and its control with diphtheria toxoid immunization". International Journal of Epidemiology. 21 (4): 807–11. doi:10.1093/ije/21.4.807. PMID 1521987.

- Hogg R. A.; Wessels J.; Hart A.; Efstratiou A.; De Zoysa G.; Mann T.; Pritchard G. C. (2009). "Possible zoonotic transmission of toxigenic Corynebacterium ulcerans from companion animals in a human case of fatal diphtheria". The Veterinary Record. 165 (23): 691–2. doi:10.1136/vr.165.23.691. PMID 19966333. S2CID 8726176.

- Freeman, Victor J (1951). "Studies on the Virulence of Bacteriophage-Infected Strains of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae". Journal of Bacteriology. 61 (6): 675–688. doi:10.1128/JB.61.6.675-688.1951. PMC 386063. PMID 14850426.

- Freeman VJ, Morse IU; Morse (1953). "Further Observations on the Change to Virulence of Bacteriophage-Infected Avirulent Strains of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae". Journal of Bacteriology. 63 (3): 407–414. doi:10.1128/JB.63.3.407-414.1952. PMC 169283. PMID 14927573.

- Holmes, R. K. (2000). "Biology and molecular epidemiology of diphtheria toxin and the tox gene". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 181 (Supplement 1): S156–S167. doi:10.1086/315554. PMID 10657208.

- "Entrez Gene: EEF2 eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2".

- Collier JR (1975). "Diphtheria toxin: mode of action and structure". Bacteriological Reviews. 39 (1): 54–85. doi:10.1128/MMBR.39.1.54-85.1975. PMC 413884. PMID 164179.

- "Immunisation and Pentavalent Vaccine". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014.

- "Horses and the Diphtheria Antitoxin". Academic Medicine. April 2000.

- Atkinson W, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, Wolfe S, eds. (2007). "Diphtheria" (PDF). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (The Pink Book) (10 ed.). Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation. pp. 59–70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2007.

- The first version of this article was adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention document "Diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae) 1995 Case Definition" Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. As a work of an agency of the U.S. government without any other copyright notice it should be available as a public domain resource.

- "Diagnosis, Treatment, and Complications". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- Laval, Enrique (March 2006). "El garotillo (Difteria) en España (Siglos XVI y XVII)". Revista Chilena de Infectología. 23 (1): 78–80. doi:10.4067/S0716-10182006000100012. PMID 16462970.

- Rogers, Robert F. (30 June 2011). Destiny's Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu, Hawai'i: University of Hawai'i Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8248-3334-3.

- "On the Treatment of Diphtheria in 1735". Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics. 55 (1): 43. 1975. doi:10.1542/peds.55.1.43. S2CID 245183270.

- Bretonneau, Pierre (1826) Des inflammations spéciales du tissu muqueux, et en particulier de la diphtérite, ou inflammation pelliculaire, connue sous le nom de croup, d'angine maligne, d'angine gangréneuse, etc. [Special inflammations of mucous tissue, and in particular diphtheria or skin inflammation, known by the name of croup, malignant throat infection, gangrenous throat infection, etc.] Paris, France: Crevot.

A condensed version of this work is available in: P. Bretonneau (1826) "Extrait du traité de la diphthérite, angine maligne, ou croup épidémique" (Extract from the treatise on diphtheria, malignant throat infection, or epidemic croup), Archives générales de médecine, series 1, 11 : 219–254. From p. 230: " … M. Bretonneau a cru convenable de l'appeler diphthérite, dérivé de ΔΙΦθΕΡΑ, … " ( … Mr. Bretonneau thought it appropriate to call it diphtheria, derived from ΔΙΦθΕΡΑ [diphthera], … ) - "Diphtheria". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Fourgeaud, Victor J. (1858). Diphtheritis: a concise historical and critical essay on the late epidemic pseudo-membranous sore throat of California (1856–7), with a few remarks illustrating the diagnosis, pathology, and treatment of the disease. California: Sacramento: J. Anthony & Co., 1858. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013.

- "Diaries and Letters – Princess Alice of Hesse and by Rhine".

- Klebs, E. (1883) "III. Sitzung: Ueber Diphtherie" (Third session: On diphtheria), Verhandlungen des Congresses für innere Medicin. Zweiter Congress gehalten zu Wiesbaden, 18.-23. April 1883 Archived 22 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Proceedings of the Congress on Internal Medicine. Second congress held at Wiesbaden, 18–23 April 1883), 2 : 139–154.

- Loeffler, F. (1884) "Untersuchungen über die Bedeutung der Mikroorganismen für die Entstehung der Diphtherie, beim Menschen, bei der Taube und beim Kalbe" (Investigations into the significance of microorganisms in the development of diphtheria among humans, pigeons, and calves), Mitteilungen aus der Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte (Communications from the Imperial Office of Health), 2 : 421–499.

- Gifford, Robert R. (March 1970). "The O'Dwyer tube; development and use in laryngeal diphtheria". Clin Pediatr (Phila). 9 (3): 179–185. doi:10.1177/000992287000900313. PMID 4905866. S2CID 37108037.

- Roux, E. and Yersin, A. (December 1888) "Contribution à l'étude de la diphthérte" Archived 15 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Contribution to the study of diphtheria), Annales de l'Institute Pasteur, 2 : 629–661.

- Parish, Henry (1965). A history of immunization. E. & S. Livingstone. p. 120.

- Behring, E. and Kitasato, S. (1890) "Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-Immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei Thieren" Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine (On the realization of diphtheria immunity and tetanus immunity among animals), Deutsche medizinsche Wochenschrift, 16 : 1113–1114.

- Kaufmann, Stefan H. E. (8 March 2017). "Remembering Emil von Behring: from Tetanus Treatment to Antibody Cooperation with Phagocytes". mBio. 8 (1): e00117–17. doi:10.1128/mBio.00117-17. PMC 5347343. PMID 28246359.

- Emil von Behring Serum Therapy in Therapeutics and Medical Science. Nobel Lecture, 12 December 1901. nobelprize.org

- H. K. Mulford Company (1903). Diphtheria Antitoxin. The Company.

- "Difference Between Serums & Vaccines | What is - YTread". youtuberead.com. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- "The Tetanus Cases in Camden, N.J". JAMA. XXXVII (23): 1539–1540. 7 December 1901. doi:10.1001/jama.1901.02470490037010.

- Lilienfeld, David E. (Spring 2008). "The first pharmacoepidemiologic investigations: national drug safety policy in the United States, 1901–1902". Perspect Biol Med. 51 (2): 188–198. doi:10.1353/pbm.0.0010. PMID 18453724. S2CID 30767303.

- Royer, Franklin (1905). "The Antitoxin Treatment of Diphtheria, with a Plea for Rational Dosage in Treatment and in Immunizing". The Therapeutic Gazette.

- Jackson R (October 2000). "Serum sickness". J Cutan Med Surg. 4 (4): 223–5. doi:10.1177/120347540000400411. PMID 11231202. S2CID 7001068.

- "United States mortality rate from measles, scarlet fever, typhoid, whooping cough, and diphtheria from 1900–1965". HealthSentinel.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- Wilson, Graham (2002). The Hazards of Immunization. Continuum International Publishing Group, Limited, 2002. p. 20. ISBN 9780485263190.

- "Iditarod: Celebrating the "Great Race of Mercy" to Stop Diphtheria Outbreak in Alaska | About | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 11 July 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Timeline". History of Vaccines. 1926 — Glenny Develops Adjuvant. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Immunology and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases – Pink Book – Diphtheria, CDC

- "Nora Isabel Wattie". MacTutor. University of St Andrews. March 2021. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- Mackie, Elizabeth M; Scott Wilson, T. (12 November 1994). "Obituary N.I.Wattie". British Medical Journal. 309: 1297.

- Baten, Joerg; Wagner (2003). "Autarky, Market Disintegration, and Health: The Mortality and Nutritional Crisis in Nazi Germany 1933–37" (PDF). Economics and Human Biology. 1–1 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1016/S1570-677X(02)00002-3. PMID 15463961. S2CID 36431705.

- Felton, Mark (2009). The Real Tenko: Extraordinary True Stories of Women Prisoners of the Japanese. Great Britain: Pen & Sword Military. p. 41. ISBN 9781848845503.

- Committee, Institute of Medicine (US) Vaccine Safety; Stratton, Kathleen R.; Howe, Cynthia J.; Richard B. Johnston, Jr (1994). Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids. National Academies Press (US).

- "Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Keja, K.; Chan, C.; Hayden, G.; Henderson, R. H. (1988). "Expanded programme on immunization". World Health Statistics Quarterly. Rapport Trimestriel de Statistiques Sanitaires Mondiales. 41 (2): 59–63. ISSN 0379-8070. PMID 3176515.

- Harnisch, JP; Tronca E; Nolan CM; Turck M; Holmes KK (1 July 1989). "Diphtheria among alcoholic urban adults. A decade of experience in Seattle". Annals of Internal Medicine. 111 (1): 71–82. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-111-1-71. PMID 2472081.

- Tatochenko, Vladimir; Mitjushin, I. L. (2000). "Contraindications to Vaccination in the Russian Federation". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 181: S228–31. doi:10.1086/315567. PMID 10657219.

- "CNN's Anderson Cooper talks with Sean Penn and Dr. Sanjay Gupta about the threat of diphtheria in Haiti". CNN. 10 May 2010. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- "Three kids die of diphtheria". The Hindu. 28 August 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- "Parents of diphtheria-stricken boy feel "tricked" by anti-vaccination groups". El Pais. 5 June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015.

- "Primer caso de difteria en España en casi 30 años". El Mundo. 2 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015.

- "WHO – Diphtheria reported cases". Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Meisje (3) overlijdt aan difterie in ziekenhuis". De Standaard. 17 March 2016. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016.

- Murali, R.S.N. (21 June 2016). "Malacca Health Dept works to contain diptheria after seven-year-old dies". thestar.com.my. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

- "Infant mortality and malaria soar in Venezuela, according to government data". Reuters. 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- "Diphtheria Reemerges as Venezuela Remains on the Brink of Economic Collapse | HealthMap". www.healthmap.org. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Diphtheria: What Exactly Is It ... And Why Is It Back?

- Nugraha, Indra Komara. "IDI: 38 Anak Meninggal karena Difteri". detiknews. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- BBC (9 November 2019). "Two cases of deadly diphtheria detected in Lothian area". BBC News.

- "Οκτάχρονος πέθανε από διφθερίτιδα στην Αθήνα - Δεν είχε εμβολιαστεί". ΑμεΑ Care (in Greek). 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Two children diagnosed with first cases of diphtheria of the throat in NSW this century". Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Taylor, Diane (20 October 2022). "Diphtheria outbreak confirmed at asylum seeker centre in Kent". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

Further reading

- Holmes, R .K. (2005). "Diphtheria and other corynebacterial infections". In Kasper; et al. (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-139140-5.

- "Antitoxin dars 1735 and 1740." The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., Vol 6, No 2. p. 338.

- Shulman, S. T. (2004). "The History of Pediatric Infectious Diseases". Pediatric Research. 55 (1): 163–176. doi:10.1203/01.PDR.0000101756.93542.09. PMC 7086672. PMID 14605240.

External links

- "Diphtheria". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Mapping diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus vaccine coverage in Africa, 2000–2016: a spatial and temporal modelling study