Acacus Mountains

The Acacus Mountains or Tadrart Akakus (Arabic: تدرارت أكاكوس / ALA-LC: Tadrārt Akākūs) form a mountain range in the desert of the Ghat District in western Libya, part of the Sahara. They are situated east of the city of Ghat, Libya, and stretch north from the border with Algeria, about 100 kilometres (62 mi). The area has a particularly rich array of prehistoric rock art.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official name | Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus |

| Location | Ghat District, Libya |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii) |

| Reference | 287 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

| Endangered | 2016–... |

| Coordinates | 24°50′N 10°20′E |

Location of Acacus Mountains in Libya | |

History

Etymology

Tadrart is the feminine form of "mountain" in the Berber languages (masculine: adrar).

Archaeology

The Acacus Mountains were occupied by hunter-gatherers continuously in the Holocene despite fluctuating climate in the African Humid Period. These sites have been important in understanding food processing and mobility as people adapted to climate variation. Animal domestication as part of the African Neolithic was introduced in this region by around 7000 BP, and pastoralism and foraging were the primary subsistence strategies of people in this region, not agriculture.

Sites in this region have been split into three main occupation periods: the Early Acacus, Late Acacus, and Pastoral Neolithic. The Early Acacus was a humid period from c. 9810 – 8880 BP characterized by small groups of mobile people living in valleys and along lowland lakes. The Late Acacus (c. 8870 – 7400 BP) was a dry period characterized by more sedentary people in larger groups living in valleys. These people greatly intensified food processing and storage of wild grains and used grinding stones and pottery extensively. The Pastoral Neolithic was characterized by increased mobility in a more humid environment again, and the domestication of animals. These people showed reduced usage of grinding stones.[1]

Rock art

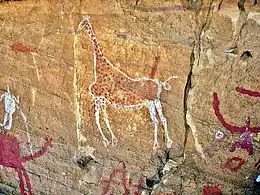

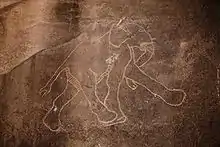

The area is known for its rock art and was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985 because of the importance of these paintings and carvings. The paintings date from 12,000 BCE to 100 CE and reflect cultural and natural changes in the area.[2]

There are paintings and carvings of animals such as giraffes, elephants, ostriches and camels, but also of humans and horses. People are depicted in various daily life situations, for example while making music and dancing.[3][4]

Giraffe

Giraffe Elephant

Elephant Pictograms

Pictograms Pictograms

Pictograms Pictograms

Pictograms

Vandalism and destruction since 1969

During Muammar Gaddafi’s rule from 1969 through 2011, the Department of Antiquities was badly neglected. Since 2005, the search for petroleum hidden underground has placed the rock art itself in danger. Seismic hammers are used to send shock waves underneath to locate oil deposits, and have noticeable effects on nearby rocks, including the ones that house the Tadrart Acacus rock art.[6]

Looting of ancient artifacts reached a level of crisis.[7] In response UNESCO called for a major awareness campaign, to heighten awareness of Libya's archaeological and cultural heritage and to alert Libyans that their heritage is "being looted by thieves and destroyed by developers."[8]

In 2012 following the murder of Gaddafi, efforts were made to train staff through a $2.26 million UNESCO project, with the Libyan and Italian governments. The project included conservation, protection and education. Along with Tadrart Acacus, Libya has four other UNESCO World Heritage sites: Cyrene, Leptis Magna, Sabratha and Ghadames.[9] UNESCO advised that "a centre should be established at Ghat or Uweynat to train the staff in charge of the protection and management of the property and to host a museum which is expected to play an important [role] in terms of awareness raising."[10]

UNESCO State of Conservation (SOC) reports from 2011, 2012 and 2013 show that at least ten of the rock-art sites have been the object of deliberate and considerable destruction since at least April 2009.[11] The ambiguity surrounding property boundaries of the World Heritage Site and therefore the property management combined with lack of local understanding of its cultural values were contributing factors in the ongoing vandalism. Conflicts in the area since 2011 led to increased vandalism.[10]

In May 2013 UNESCO undertook a technical mission to assess the state of conservation the Tadrart Acacus site and to "build-up a strategic plan to enforce the protection and management of this unique cultural and natural context."[12]

On 14 April 2014 two kinds of vandals were reported, those who thoughtlessly carve their own names beside the ancient rock art and those who deliberately use chemical products to remove the rock drawings.[13] On April 20, 2014, the French special correspondent Jacques-Marie Bourget was informed by a local journalist from Ghat, Libya, Aziz Al-Hachi, that the UNESCO Rock-Art World Heritage Site of Tadrart Acacus was being destroyed with sledgehammers and scrub brushes.[14][15]

Geography

The Tadrart Acacus have a large variation of landscapes, from different-coloured dunes to arches, gorges, isolated rocks and deep wadis (ravines). Major landmarks include the arches of Afzejare and Tin Khlega. Although this area is one of the most arid in the Sahara, there is vegetation, such as the medicinal Calotropis procera, and there are a number of springs and wells in the mountains.

Rock arch in Tadrart Acacus

Rock arch in Tadrart Acacus The Moul n'ga Cirque in the Tadrart Rouge region, with wave clouds above

The Moul n'ga Cirque in the Tadrart Rouge region, with wave clouds above Desert of Akakus

Desert of Akakus Head rock

Head rock Rock formations

Rock formations Rock formations

Rock formations Temporary human-built habitat

Temporary human-built habitat

See also

Notes

- Garcea, Elena A. A. (2004-06-01). "An Alternative Way Towards Food Production: The Perspective from the Libyan Sahara". Journal of World Prehistory. 18 (2): 107–154. doi:10.1007/s10963-004-2878-6. ISSN 1573-7802. S2CID 162218030.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "UNESCO Fact Sheet". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- Jebel Acacus Map and Guide (Map) (1st ed.). 1:100,000, inset 1:400,000. Tourist and cave art information. Cartography by EWP. EWP. 2006. ISBN 0-906227-93-3. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- "Acacus Rock Art Photo Gallery". Ewpnet.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-01. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- Gifford-Gonzalez, Diane (2013). "Animal Genetics and African Archaeology: Why It Matters". African Archaeological Review. 30: 1–20. doi:10.1007/s10437-013-9130-7.

- Bohannon, John (10 February 2005). "In the Valley of Life, Oil is Death to the Art of a Lost Civilization". The Guardian.

- Little, Tom (23 December 2013), Libyan archaeologists look to the future with new training, Libyan Herald, retrieved 5 May 2014

- UNESCO training to combat the looting of Libyan antiquities, Libyan Herald, 25 September 2013, retrieved 5 May 2014

- UNESCO supports Libyan Heritage with $2m Project, Libya Business News, 7 December 2012, retrieved 5 May 2014

- State of Conservation (SOC): Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus, 2013, retrieved 4 May 2014

- State of Conservation (SOC): Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus, 2011, retrieved 4 May 2014

- UNESCO organizes training course for conservation and restores of Libyan Artefacts, United Nations, 2013, retrieved 5 May 2014

- Grira, Sarra (14 April 2014), Graffiti defaces prehistoric rock art in Libya, Observers: France 24, archived from the original on 11 October 2014, retrieved 5 May 2014

- Libye : Les salafistes wahhabites libyens détruisent un site de 12.000 ans d'âge, Algeria, 29 April 2014

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bourget, Jacques-Marie (2014-04-20), Libye, 12 000 ans effacés au white spirit, Mondafrique, archived from the original on 2014-05-05, retrieved 2014-05-04

Further reading

- Di Lernia, Savino e Zampetti, Daniela (eds.) (2008) La Memoria dell'Arte. Le pitture rupestri dell'Acacus tra passato e futuro, Florence, All'Insegna del Giglio;

- Minozzi S., Manzi G., Ricci F., di Lernia S., and Borgognini Tarli S.M. (2003) "Nonalimentary tooth use in prehistory: an Example from Early Holocene in Central Sahara (Uan Muhuggiag, Tadrart Acacus, Libya)" American Journal of Physical Anthropology 120: pp. 225–232; doi:10.1002/ajpa.10161

- Mattingly, D. (2000) "Twelve thousand years of human adaptation in Fezzan (Libyan Sahara)" in G. Barker, Graeme and Gilbertson, D.D. (eds) The Archaeology of Drylands: Living at the Margin London, Routledge, pp. 160–79;

- Cremaschi, Mauro and Di Lernia, Savino (1999) "Holocene Climatic Changes and Cultural Dynamics in the Libyan Sahara" African Archaeological Review 16(4): pp. 211–238; doi:10.1023/A:1021609623737

- Cremaschi, Mauro; Di Lernia, Savino; and Garcea, Elena A. A. (1998) "Some Insights on the Aterian in the Libyan Sahara: Chronology, Environment, and Archaeology" African Archaeological Review 15(4): pp. 261–286; doi:10.1023/A:1021620531489

- Cremaschi, Mauro and Di Lernia, Savino (eds., 1998) Wadi Teshuinat: Palaeoenvironment and Prehistory in South-western Fezzan (Libyan Sahara) Florence, All'Insegna del Giglio;

- Wasylikowa, K. (1992) "Holocene flora of the Tadrart Acacus area, SW Libya, based on plant macrofossils from Uan Muhuggiag and Ti-n-Torha Two Caves archaeological sites" Origini 16: pp. 125–159;

- Mori, F., (1960) Arte Preistorica del Sahara Libico Rome, De Luca;

- Mori, F., (1965) Tadrart Acacus, Turin, Einaudi;

- Mercuri AM (2008) Plant exploitation and ethnopalynological evidence from the Wadi Teshuinat area (Tadrart Acacus, Libyan Sahara). Journal of Archaeological Science 35: 1619-1642; doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.003

- Mercuri AM (2008) Human influence, plant landscape evolution and climate inferences from the archaeobotanical records of the Wadi Teshuinat area (Libyan Sahara). Journal of Arid Environments 72: 1950-1967. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.04.008