Dwight Gooden

Dwight Eugene Gooden (born November 16, 1964), nicknamed "Dr. K" and "Doc", is an American former professional baseball pitcher who played 16 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). Gooden pitched from 1984 to 1994 and from 1996 to 2000 for the New York Mets, New York Yankees, Cleveland Indians, Houston Astros, and Tampa Bay Devil Rays. In a career spanning 430 games, he pitched 2,800+2⁄3 innings and posted a win–loss record of 194–112, with a 3.51 earned run average (ERA), and 2,293 strikeouts.

| Dwight Gooden | |

|---|---|

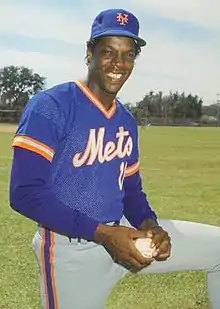

Gooden with the New York Mets in 1986 | |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: November 16, 1964 Tampa, Florida, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 7, 1984, for the New York Mets | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 29, 2000, for the New York Yankees | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 194–112 |

| Earned run average | 3.51 |

| Strikeouts | 2,293 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Gooden made his MLB debut in 1984 for the Mets and quickly established himself as one of the league's most talented pitchers; as a 19-year-old rookie, he earned the first of four All-Star selections, won the National League (NL) Rookie of the Year Award, and led the league in strikeouts. In 1985, he won the NL Cy Young Award and achieved the pitching Triple Crown, compiling a 24–4 record and a league-leading 1.53 ERA, 268 strikeouts, and 16 complete games. The following season, he helped the Mets win the 1986 World Series.

Gooden remained an effective pitcher in subsequent years, but his career was ultimately derailed by cocaine and alcohol addiction. After posting a losing record in each season from 1992 to 1994, Gooden was suspended for the 1995 season after a positive drug test while serving a prior suspension. As a member of the Yankees in 1996, Gooden pitched a no-hitter and helped the team on its path to a World Series championship. He pitched four additional years for as many teams, but never approached the success of his peak years with the Mets. In 2010, Gooden was inducted into the New York Mets Hall of Fame. Gooden's troubles with addiction continued after his retirement from baseball and resulted in several arrests. He was incarcerated for seven months in 2006 after violating the terms of his probation.

Career

Gooden attended Hillsborough High School in Tampa where he was teammates on the school's baseball team with Vance Lovelace.[1] A native of Tampa, Florida, Dwight Gooden was drafted in the first round in 1982, the fifth player taken overall. He spent one season in the minors, in which he led the Class-A Carolina League in wins, strikeouts and ERA while playing for the Lynchburg Mets. Gooden had 300 strikeouts in 191 innings, a performance which convinced Triple-A Tidewater Tides manager and future Mets manager Davey Johnson to bring him up for the Tides' postseason.

1984

Gooden made the rare jump from High-A directly to the major leagues in one year, bypassing Double-A and Triple-A. He made his major-league debut on April 7, 1984, with the New York Mets at the age of 19. He quickly developed a reputation with his 98 miles per hour (158 km/h) fastball and sweeping curveball, which was given the superlative nickname of "Lord Charles", in contrast with "Uncle Charlie", a common nickname for a curveball. He was dubbed "Dr. K", in reference to the letter "K" being the standard abbreviation for strikeout, which soon became shortened to "Doc". Gooden soon attracted a rooting section at Shea Stadium that called itself "The K Korner", and would hang up cards with a red "K" after each of his strikeouts.

When he took the mound in the fifth inning on July 10, 1984, Gooden became the youngest player to appear in an All-Star Game. He complemented this distinction by striking out the side, AL batters: Lance Parrish, Chet Lemon, and Alvin Davis. Setting up Gooden, NL Pitcher Fernando Valenzuela had already struck out the side in the fourth, putting down future Hall of Famers Dave Winfield, Reggie Jackson, and George Brett. The two pitchers' combined performance broke an All-Star game record, coincidentally on its celebrated 50th anniversary—Carl Hubbell's five consecutive strikeouts in 1934.

That season, Gooden won 17 games, the most by a 19-year-old since Wally Bunker won 19 games in 1964 and the second most for a Mets rookie, after Jerry Koosman's 19 wins in 1968. Gooden won eight of his last nine starts; in his final three starts of the 1984 season, he had 41 strikeouts and 1 walk. Gooden led the league in strikeouts, his 276 breaking Herb Score's rookie record of 245 in 1955, and also set the record for most strikeouts in three consecutive starts with 43. As a 19-year-old rookie, Gooden set the then-major league record for strikeouts per 9 innings, with 11.39, breaking Sam McDowell's record of 10.71 in 1965. He was voted the Rookie of the Year, giving the Mets two consecutive winners of that award (Darryl Strawberry had been the recipient in 1983). Gooden also became the third Mets pitcher to win the award, joining Tom Seaver (1967) and Jon Matlack (1972). Gooden finished second in the NL Cy Young Award voting, even though he had more NL wins, strikeouts, innings pitched, and a lower ERA than the NL winner, Rick Sutcliffe.[2][3][4]

1985

In 1985, Gooden pitched one of the most statistically dominating single seasons in baseball history. Leading Major League Baseball with 24 wins, 268 strikeouts, and a 1.53 ERA (the second-lowest in the live-ball era, trailing only Bob Gibson's 1.12 in 1968) Gooden earned the major leagues' pitching Triple Crown. He led the National League in complete games (16) and innings pitched (2762⁄3). From his second start onward, Gooden's ERA never rose above 2.00.[5] At age 20, he was the youngest pitcher of the last half-century to have an ERA+ above 200. Gooden's ERA+ was 229; 23-year-old Dean Chance (200 ERA+ in 1964) was the only other pitcher under the age of 25 to do so. From August 31 through September 16, Gooden threw 31 consecutive scoreless innings over four games, and through October 2, threw 49 consecutive innings over seven games without allowing an earned run. The highest "quality start" percentage for a given season was recorded by Dwight Gooden, who had 33 of them in 35 games in 1985.

In September, he pitched back-to-back nine-inning games allowing no runs, but received no-decisions in both games. In his four losses, Gooden allowed 26 hits and five walks in 28 innings, with 28 strikeouts and a 2.89 ERA. The Mets finished second in the 1985 NL East, and teammates jokingly blamed Gooden for having lost 4 games, thereby mathematically costing them the division title. That year, Gooden became one of only 15 black pitchers ever to win 20 games, the most recent of whom was David Price. Gooden became the youngest-ever recipient of the Cy Young Award and Pitcher of the Year Award. There was even media speculation about Gooden's Hall of Fame prospects. That November, Gooden turned 21.

Travelers descending the steps of the side entrance to Manhattan's Pennsylvania Station were greeted by an enormous photograph of Gooden in mid-motion that recorded his season's strikeout totals as the year progressed. Likewise, those strolling the streets of Manhattan's West Side could gaze up at a 102 feet tall Sports Illustrated mural of Gooden painted on the side of a building at 351 West 42nd Street in Times Square, whose caption asked "How does it feel to look down the barrel of a loaded gun?"[6][7][8][9] In a span of 50 starts from August 11, 1984, to May 6, 1986, Gooden posted a record of 37–5 with a 1.38 ERA; he had 412 strikeouts and 90 walks in 406 innings.

1986

In 1986, he compiled a 17–6 record. Gooden's 200 strikeouts were fifth in the National League, but more than a hundred behind the league leader, Mike Scott of the Houston Astros and a tremendous decrease from his first two seasons. As the 1986 season progressed, Gooden noticed that his fastball, which had been consistently in the mid-90s, had lost just a bit of its zip. “That impossible-to-track, impossible-to-time movement deserted me in 1986, and never returned,” he said.[10] Gooden had compiled a strikeouts per nine innings pitched of 10.05 for this first two seasons. He would finish with a Strikeouts per nine innings of just 5.91 for the rest of his career.

In another All-Star record pertaining to youth, in 1986 Gooden became the youngest pitcher to start an All-Star Game at 21 years, 241 days of age. Gooden was the Mets ace going into the playoffs, and his postseason started promisingly. He lost a 1–0 duel with Scott in the NLCS opener, then got a no-decision in Game 5, pitching 10 innings of one-run ball. He was substantially worse in the World Series against the Boston Red Sox, not getting past the 5th inning in either of his two starts. Nevertheless, the Mets won four of the five non-Gooden starts and the championship. In an early red flag, Gooden failed to attend the team's victory parade (he would admit after his retirement that during the parade, he had been using drugs at his dealer's apartment).[11]

Early drug problems and injuries

Gooden was arrested on December 13, 1986, in Tampa, Florida after being assaulted by police.[12] A report clearing police of misconduct in the arrest helped start the Tampa riots of 1987.[13] Rumors of substance abuse began to arise, which were confirmed when Gooden tested positive for cocaine during spring training in 1987. He entered a rehabilitation center on April 1, 1987, to avoid being suspended and did not make his first start of the season until June 5. Despite missing a third of the season, Gooden won 15 games for the 1987 Mets. In 1988, he was profiled in the William Goldman and Mike Lupica book Wait Till Next Year, which looked at the impact Gooden's drug use and enforced missed games had on the Mets over the 1987 season.

1988

In 1988, Gooden recorded an 18–9 record as the Mets returned to the postseason. In the first game of the NLCS against the Los Angeles Dodgers, Gooden was matched against Orel Hershiser, who had just finished the regular season with a 59-inning scoreless streak. Gooden pitched well, allowing just 4 hits and recording 10 strikeouts, but left after seven innings trailing 2–0. In Game 4, Gooden entered the ninth inning with a 4–2 lead and the chance to give his Mets a commanding 3–1 advantage in the series. But he allowed a game-tying home run to Mike Scioscia, and the Dodgers eventually went on to win the game in 12 innings, and the series as well, 4 games to 3.

1989–91

Gooden suffered a shoulder injury in 1989, which reduced him to a 9–4 record in 17 starts. He rebounded in 1990, posting a 19–7 season with 223 strikeouts, second only to teammate David Cone's 233. However, after another injury in 1991, Gooden's career declined significantly. Though drug abuse is commonly blamed for Gooden's pitching troubles, some analysts point to his early workload. It has been estimated that Gooden threw over 10,800 pitches from 1983 to 1985, a period in which he was 18 to 20 years old.[14] Gooden hurled 276 innings in his historic 1985 season; as of the end of the 2017 season, only two subsequent pitchers have thrown that many innings (Charlie Hough, a knuckleballer, and Roger Clemens, both in 1987). By the time he reached his 21st birthday, Gooden had already accumulated 928 strikeouts between the minor and major leagues.

On August 9, 1990, Phillies pitcher Pat Combs struck Gooden in the knee with the first pitch of the bottom of the fifth inning. Gooden, seeing the pitch as retaliation for him having hit two Phillies batters, charged the mound, setting off a bench-clearing brawl. Gooden was one of six players ejected.[15]

Gooden was accused of rape along with teammates Vince Coleman and Daryl Boston in 1991; however, charges were never pressed.[16]

1992–95

1992 was Gooden's first-ever losing season (10–13); it was also the first time he had lost as many as 10 decisions. 1993 was no improvement, as Gooden finished 12–15. During the 1993 season, Sports Illustrated ran a cover story on Gooden entitled, "From Phenom to Phantom."

During the strike-shortened 1994 season at age 29, Gooden had a 3–4 record with a 6.31 ERA when he tested positive for cocaine use and was suspended for 60 days. He tested positive again while serving the suspension, and was further suspended for the entire 1995 season. The day after receiving the second suspension, Gooden's wife, Monica, found him in his bedroom with a loaded gun to his head.[17]

In July 1995, the famous longstanding Dwight Gooden Times Square mural was replaced with a Charles Oakley mural. The Dwight Gooden mural was a part of the NYC landscape for over ten years.[18]

Kirk Radomski, the New York Mets clubhouse attendant whose allegations are at the base of the Mitchell Report later claimed that he took two urine tests for Gooden during the 1990s. Gooden denies the allegations.[19]

1996–2000: New York Yankees and three other teams

Gooden signed with the New York Yankees in 1996 as a free agent. After pitching poorly in April and nearly getting released, he was sent down to the minors where he worked on his mechanics and soon returned with a shortened wind-up. He no-hit the Seattle Mariners 2–0 at Yankee Stadium on May 14;[20] the no-hitter was the first by a Yankee right-hander since Don Larsen's perfect game in the 1956 World Series, and the first by a Yankee right-hander during the regular season since Allie Reynolds' second no-hitter in 1951. He ended the 1996 season at 11–7, his first winning record since 1991, and showed flashes of his early form, going 10–2 with a 3.09 ERA from April 27 through August 12. He proved to be a valuable asset for the Yankees that season as David Cone was out until early September with an aneurysm in his shoulder.

Gooden was left off the 1996 postseason roster due to injury and fatigue. In 1997, he posted a respectable 9–5 record with a 4.91 ERA. He had one start for the Yankees in the 1997 ALDS against the Cleveland Indians; coincidentally, he again faced his 1988 postseason nemesis Orel Hershiser. Gooden left Game 4 during the sixth inning with a 2–1 lead, but the Yankee bullpen faltered in the 8th, and Gooden was left with the no-decision.

Gooden then signed with the Cleveland Indians and enjoyed moderate success in 1998, going 8–6 with a 3.76 ERA. He started two games in the 1998 post-season, getting a no-decision against the Boston Red Sox and a loss to his former team, the Yankees. He remained with the Indians in 1999 but did not match his respectable numbers from the previous year, going 3–4 with a 6.26 ERA.

In 1999, Gooden released an autobiography titled Heat, in which he discussed his struggles with alcohol and cocaine abuse.

Gooden began the 2000 season with two sub-par stints with the Houston Astros and Tampa Bay Devil Rays but found himself back with the Yankees mid-season. He would go on to have a respectable second stint with the Yankees, going 4–2 with a 3.36 ERA as a spot starter and long reliever, including a win against his former team, the Mets, on July 8 in the regular-season Subway series. He made one relief appearance in each of the first two rounds of the playoffs, both times with the Yankees trailing. Gooden did not pitch in the 2000 World Series against the Mets, though 2000 would be the third time Gooden received a World Series ring in his career.

Postseason career

Gooden failed to win a postseason game, going 0–4 in the course of nine postseason starts over eight series.[21] In the 1986 National League Championship Series, however, he had an earned run average of only 1.06 after starting two games and allowing just two earned runs in 17 innings pitched.[21]

Batting and fielding

For a pitcher, Gooden was an above average hitter, posting a .196 batting average (145-for-741) with 60 runs, 15 doubles, 5 triples, 8 home runs, 67 RBI and 14 bases on balls. He recorded a .950 fielding percentage, which was five points lower than the league average at his position.[21]

Retirement

Gooden retired in 2001 after he was cut by the Yankees in spring training,[22] ending his career with a record of 194–112. More than half of those wins came before age 25.

Gooden appeared on the 2006 Baseball Hall of Fame ballot. He was named on only 17, or 3.3 percent, of the 520 voting writers' ballots, and, having been named on less than 5 percent of the total ballots, was removed from future HOF consideration.

After retiring, Gooden took a job in the Yankees' front office. He acted as the go-between man during free agent contract negotiations between his nephew, Gary Sheffield, and the Yankees prior to the 2004 season. In July 2009 he was hired as a vice president of community relations for Atlantic League's Newark Bears. He left the post in November of the same year.[23]

Gooden appeared at the Shea Stadium final celebration on September 28, 2008, the first time he had appeared at Shea Stadium since 2000. On April 13, 2009, he made an appearance at the newly opened Citi Field. Gooden spontaneously signed his name to a wall on the inside of the stadium. The Mets initially indicated that they would remove the signature, but soon decided instead to move the part of the wall with Gooden's writing to a different area of the stadium and acquire additional signatures from other popular ex-players. On August 1, 2010, he was officially inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame along with Darryl Strawberry, Frank Cashen, and Davey Johnson. He also threw out the ceremonial first pitch on the same day to Gary Carter.

VH1 Network announced June 11, 2011, that he would be a patient in VH1's fifth season of the reality show Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew.

In August 2023, the Mets announced that they will retire Gooden's number 16 - along with the number 18 of former teammate Darryl Strawberry - in 2024.[24]

Legal troubles

In December 1986, Gooden was arrested in Tampa alongside nephew Gary Sheffield and former high school teammate Vance Lovelace after police stopped his Chevrolet Corvette. He was charged with resisting arrest with violence, battery on a police officer and disorderly conduct.[1] He pleaded no contest in January 1987 and was sentenced to three years probation and 160 hours of community service.[25]

On February 20, 2002, Gooden was arrested in Tampa and charged with driving while intoxicated, having an open container of alcohol in his vehicle, and driving with a suspended license. He was arrested again in January 2003 for driving with a suspended license. On March 12, 2005, Gooden was again arrested in Tampa for punching his girlfriend after she threw a telephone at his head. He was released two days later on a misdemeanor battery charge.

On August 23, 2005, Gooden drove away from a traffic stop in Tampa after being pulled over for driving erratically. He gave the officer his driver's license, twice refused to leave his car, and then drove away. The officer remarked in his report that Gooden's eyes were glassy and bloodshot, his speech was slurred, and a "strong" odor of alcohol was present on him. Three days after the traffic stop, Gooden turned himself in to police.[26]

Gooden was again arrested in March 2006 for violating his probation, after he arrived high on cocaine at a scheduled meeting with his probation officer, David R. Stec.[27] He chose prison over extended probation, perhaps in the hope that incarceration would separate him from the temptations of his addiction.[28] He entered prison on April 17, 2006. On May 31, Gooden said in an interview from prison, "I can't come back here ... I'd rather get shot than come back here ... If I don't get the message this time, I never will."[29] Gooden was released from prison November 9, 2006, after nearly seven months' incarceration and was not placed on further probation.[30]

On the morning of March 24, 2010, Gooden was arrested in Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, near his home there, after leaving the scene of a traffic accident, having been located nearby and found to be under the influence of an undisclosed controlled substance.[31] He was charged with DWI with a child passenger, leaving the scene of an accident, and other motor vehicle violations.[32] Gooden was also charged with endangering the welfare of a child because a child was with him at the time of the accident.[33] He later pleaded guilty to child endangerment, received five years' probation, and was ordered to undergo outpatient drug treatment.[34]

Gooden was arrested for cocaine possession in Holmdel Township, New Jersey on June 7, 2019. Gooden had been stopped by police for driving too slowly and having illegally tinted windows when they discovered two baggies suspected of containing cocaine. Gooden was charged with possession of a controlled substance, possession of drug paraphernalia and driving under the influence and faced up to five years in prison if convicted.[35] He pleaded guilty to one charge of possessing cocaine in August and was sentenced to a year probation in November 2020.[36]

Yet another arrest for driving while intoxicated occurred on July 22, 2019, this time in Newark, New Jersey.[37] Gooden had been due in court to answer for the cocaine possession arrest in June the day after his arrest in July.[38]

In popular culture

American rock band the Mountain Goats released a song entitled "Doc Gooden" on their 2019 album In League with Dragons. The lyrics, written by John Darnielle, include references to life as a baseball player.

American rapper Action Bronson mentioned Gooden in his 2015 song "Baby Blue".

The baseball video game MLB Power Pros uses Gooden's Dr. K nickname as the name for an ability that makes pitchers pitch well with two strikes.

See also

- List of doping cases in sport

- List of Major League Baseball annual ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball no-hitters

- Sporting News Pitcher of the Year Award

- Triple Crown (baseball)

References

- "Mets' ace Gooden arrested". The Lincoln Star. Associated Press. December 15, 1986. p. 13. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- "NL Cy Young Voting". Baseball-Reference.com.

- "Dwight Gooden Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- "Rick Sutcliffe Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- "Dwight Gooden 1985 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- Coffey, Wayne (November 14, 2009). "Twenty-five years after his phenomenal rookie season, Dwight Gooden takes aim at his demons". New York: NY Daily News. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- Higbie, Andrea (May 4, 1997). "Young Artist Seeks Brush With Subject – New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "A fading picture". The Sporting News. Find Articles. November 14, 1994. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- Salvatore, Bryan Di (August 1, 2011). "The Talk of the Town: Doc". The New Yorker. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- "Dwight Gooden's Historic 1985 Season". Fangraphs. April 14, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- "Gooden missed Mets' 1986 parade doing drugs". ESPN.com. October 19, 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Newspaper Archives". St. Petersburg Times.

- "Newspaper Archives". St. Petersburg Times.

- "Ten Things I Didn't Know Last Week". The Hardball Times. September 22, 2005. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- Sexton, Joe (August 10, 1990). "In a Bruising Outing, the Mets Rally and Win". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- Claire Smith (April 2, 1992). "Baseball; Mets Rape Case Transferred To the Florida State Attorney". The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- "Gooden Discloses Near Suicide Attempt". Apnewsarchive.com. June 21, 1996. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- Higbie, Andrea (July 16, 1995). "NOTICED; Gooden Is Benched Again". The New York Times. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- David Justice, Dwight Gooden Deny Kirk Radomski's Allegations ESPN.com, January 27, 2009

- "Gooden Pitches No-Hitter as Yankees Top Mariners, 2–0". The New York Times.

- "Dwight Gooden Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- Romano, John (March 31, 2001). "With the lead, Gooden retires". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- Police: Former Yankees and Mets pitcher Dwight Gooden arrested on alleged DWI with 5-year-old son in the car NorthJersey.com, March 24, 2010

- DiComo, Anthony (August 24, 2023). "Mets to retire Strawberry and Gooden's numbers in 2024". MLB.com.

- "Gooden Pleads No Contest, Gets Probation". The Los Angeles Times. January 24, 1987. p. 47. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- "Gooden arrested after turning self in on felony charges – MLB – ESPN". ESPN.com. August 26, 2005. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Gooden arrested for violating terms of probation – MLB – ESPN". ESPN.com. March 14, 2006. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Doc's savior sadly could be time spent behind bars – MLB – ESPN". ESPN.com. April 6, 2006. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- "Gooden says he'd rather be shot than jailed again – MLB – ESPN". ESPN.com. May 31, 2006. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Cy Young winner Gooden released from Florida prison – MLB – ESPN". ESPN.com. November 10, 2006. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Wills, Kerry; and McShane, Larry. "Ex-Mets star Dwight Gooden not ready to talk about drug charge stemming from crash with son in car" Archived March 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Daily News (New York), March 25, 2010. Accessed January 28, 2011. "'When the time is right, I will,' Gooden said outside his home in Franklin Lakes, N.J. 'Now is not the time. Sorry.'"

- "Dwight Gooden Charged With DWI (Update)". Deadspin.com. March 24, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- Staff, the CNN Wire. "Police: Ex-Mets pitcher arrested, accused of DUI with child in car - CNN.com". cnn.com.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - "Dwight Gooden gets probation in NJ DUI case". Fox News. April 15, 2011.

- Draper, Kevin (July 12, 2019). "Dwight Gooden Arrested on Drug Charges in New Jersey". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- "Gooden gets probation for 2019 drug arrest". ESPN.com. ESPN. Associated Press. November 13, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- "DWI charges for Gooden; 2nd arrest in 2 months". ESPN.com. July 23, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Ex-Mets Pitcher Dwight Gooden Arrested for DUI". Sports Illustrated. July 23, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Dwight Gooden at IMDb

| Achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gilberto Reyes 1983 |

Youngest Player in the National League 1984 |

Succeeded by José González 1985 |

| Preceded by | National League Pitching Triple Crown 1985 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | No-hitter pitcher May 14, 1996 |

Succeeded by |