Dolichorhynchops

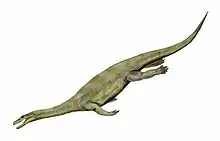

Dolichorhynchops is an extinct genus of polycotylid plesiosaur from the Late Cretaceous (early Turonian to late Campanian stage) of North America, containing three species, D. osborni, D. bonneri and D. tropicensis,[1] as well as a questionably referred fourth species, D. herschelensis.[2] Dolichorhynchops was a prehistoric marine reptile, but at least one species, D. tropicensis, likely entered rivers to collect gastroliths. Its Greek generic name means "long-nosed face". While typically measuring about 3 metres (9.8 ft) in length, the largest specimens of D. osborni and D. bonneri are estimated to have a total body length more than approximately 4.29 metres (14.1 ft) and 5.09 metres (16.7 ft), respectively.

| Dolichorhynchops Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| D. osborni, National Museum of Natural History, Washington D. C. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Polycotylidae |

| Genus: | †Dolichorhynchops Williston, 1902 |

| Type species | |

| †Dolichorhynchops osborni Williston, 1902 | |

| Other species | |

Discovery and species

D. osborni

The holotype specimen of Dolichorhynchops osborni, KUVP 1300, was discovered in the upper Smoky Hill Chalk Logan County, Kansas, by George F. Sternberg, as a teenager, in around 1900. The remains were collected by him and his father, Charles H. Sternberg, and then sold to the University of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas). KUVP 1300[3] was prepared and mounted by H.T. Martin under the supervision of Dr. Samuel Wendell Williston, who described and named it in 1902. A more detailed description and photographs were provided by Williston 1903). The specimen has been on display in the KU Museum of Natural History since that time. Everhart 2004b estimated that the holotype had a skull measuring 57 cm (1.87 ft) long.

In 1918, Charles H. Sternberg found a large mosasaur, Tylosaurus, with the remains of a plesiosaur in its stomach.[4] The mosasaur specimen is currently mounted in the United States National Museum (Smithsonian) and the plesiosaur remains are stored in the collections. Although these important specimens were briefly reported by Sternberg 1922, the information was lost to science until 2001. This specimen was rediscovered and described by Everhart 2004a. It is the basis for the story line in the 2007 National Geographic IMAX documentary Sea Monsters: A Prehistoric Adventure, and a book by the same name Everhart 2007.

George Sternberg found a second, less complete specimen of D.osborni in 1926. In his effort to sell the specimen to a museum, Sternberg took detailed photographs of the skull.[5] The specimen was eventually mounted in plaster and was acquired by the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. MCZ 1064[6] was on display there until some time in the 1950s. This specimen was never completely described although the skull was figured by O'Keefe 2004. (See also Everhart 2004b)

The specimen of D. osborni on exhibit at the Sternberg, FHSM VP-404[7] was found by Marion Bonner near Russell Springs in Logan County in the early 1950s. Carpenter 1996 estimated that FHSM VP-404, with a skull measuring 51.3 centimetres (1.68 ft) long, had a total body length of approximately 3.07 metres (10.1 ft). The skull[8] was crushed flat but is in very good condition. This specimen was initially reported by Sternberg & Walker 1957, and then was the subject of a Masters thesis by Bonner 1964. Note that it was described by Bonner as "Trinacromerum osborni" which was the accepted genus name at the time.

Larger specimens of D. osborni have been reported: UNSM 50133 had an estimated skull length of 61.8 centimetres (2.03 ft), while AMNH 5834 had an estimated skull length of 74.5 centimetres (2.44 ft) (see Carpenter 1996). Carpenter 1996 estimated that AMNH 5834 had a total body length of more than approximately 4.29 metres (14.1 ft).

Until recently, all known specimens of D. osborni in Kansas had been collected from the upper layers of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Campanian age). Everhart 2003 reported the first remains from the lower chalk (Late Coniacian-Santonian in age). In 2005, the remains of the earliest known D. osborni were discovered in the Fort Hays Limestone, Niobrara Formation in Jewell County, Kansas. This is the first record of a polycotylid plesiosaur in this formation.[9]

D. bonneri

Two very large specimens of a polycotylid plesiosaur (KUVP 40001 and 40002[10]) were collected from the Pierre Shale of Wyoming and later reported on by Adams in her 1977 Masters thesis.[11] Later (1997), she officially described (1997) as a new species of Trinacromerum (T. bonneri). Unknown to her at the time, Carpenter (1996) had revised the Polycotylidae and separated Dolichorhynchops from Trinacromerum, raising the question as to whether or not the specimens represented a separate species or just larger individuals of D. osborni. A study in 2008 found that T. bonneri is a valid species of Dolichorhynchops, D. bonneri.[12] Carpenter 1996 estimated that KUVP 40001, with a skull measuring 98 centimetres (3.22 ft) long, had a total body length of more than approximately 5.09 metres (16.7 ft).

D. herschelensis

D. herschelensis was described as a new species by Tamaki Sato in 2005. It was discovered in the Bearpaw Formation of Saskatchewan, Canada, a Late Cretaceous (late Campanian to Maastrichtian) rock formation. The fossil was found close to the town of Herschel in southwestern Saskatchewan, from which the species name is derived. The rock formation it was found in consists of sandstones, mudstones and shales laid down in the Western Interior Seaway, just before it began to revert to dry land.[13]

The type specimen of D. herschelensis was discovered in a disarticulated state (i.e. the bones were scattered about the discovery site). The skull, lower jaw, ribs, pelvis and shoulder blades were all recovered, but the spine was incomplete, so the exact number of vertebrae the living animal would have had is unknown. All four limbs are missing, with the exception of 9 small Phalanges (finger bones) and a small number of limb bones found close by which may belong to the animal in question.[13]

The specimen is believed to be an adult, due to the fusion of certain bones (it is generally assumed—not necessarily strictly correctly so—that other animals' skulls, much as humans', consist of dissociated bones interconnected by cartilage fontanelles that do not entirely close until full maturity). It is also believed to have been substantially smaller than its close relative, D. osborni, as some juvenile specimens of D. osborni are larger than the adult specimen of D. herschelensis. Assuming that only a few vertebrae are missing from the skeleton, the animal is estimated to be about 2.5–3 metres (8.2–9.8 ft) in length. The snout is long and thin, with numerous tooth sockets. However, very few of the thin, sharp teeth remain.[13]

D. tropicensis

D. tropicensis was first named by Rebecca Schmeisser McKean in 2011. The specific name is derived from the name of the Tropic Shale, in which the two specimens of D. tropicensis were found. It is known from the holotype MNA V10046, an almost complete, well-preserved 3.2 metres (10.5 ft) long skeleton including the most of the skull and from the referred specimen MNA V9431, fragmentary postcranial elements. It was collected by the Museum of Northern Arizona from a single locality within the Tropic Shale of Utah, dating to the early Turonian stage of the early Late Cretaceous, about 93.5-91 million years ago. D. tropicensis extends the known stratigraphic range for Dolichorhynchops back by approximately 7 million years.[1] Previously three additional polycotylid taxa, Eopolycotylus, Palmulasaurus and Trinacromerum, have been named from the same formation, two of which are currently endemic to the Tropic Shale.[14]

The holotype is associated with 289 gastroliths, which is unusual in comparison to most polycotylid skeletons that generally lack gastroliths. Ranging from less than 0.1 grams to 18.5 grams, the total mass of the gastroliths was about 518 grams. About three-quarters of the stones weighed less than 2 grams, with the mean mass and median mass of the stones respectively estimated at 1.9 grams and 0.8 grams. The gastroliths had high mean value and variability in sphericity, suggesting that this individual was obtaining its stones from rivers located along the western side of the Western Interior Seaway.[15]

Classification

Below is a cladogram of polycotylid relationships from Ketchum & Benson, 2011.[2]

| Plesiosauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Schmeisser McKean 2011

- Hilary F. Ketchum & Roger B. J. Benson (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 109–129.

- "Image: plio-lrg.jpg, (2175 × 600 px)". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- "Tylosaur food". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- "Image: mcz5086a.jpg, (1336 × 742 px)". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- "Image: 1064-4.jpg, (1000 × 297 px)". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- "Image: vp-404.jpg, (1160 × 404 px)". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- "VP-404 skull". oceansofkansas.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-05. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- Everhart, Decker & Decker 2006

- "Image: KU40001-4.jpg, (589 × 500 px)". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- Adams 1977

- O'Keefe, F. R. (2008). "Cranial anatomy and taxonomy of Dolichorhynchops bonneri new combination, a polycotylid (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Pierre Shale of Wyoming and South Dakota". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (3): 664–676. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[664:caatod]2.0.co;2. S2CID 32099438.

- Sato 2005

- Albright III, Gillette & Titus 2007b

- Schmeisser, R.L.; Gillette, D.D. (2009). "Unusual occurrence of gastroliths in a polycotylid plesiosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Tropic Shale, southern Utah". PALAIOS. 24 (7): 453–459. Bibcode:2009Palai..24..453S. doi:10.2110/palo.2008.p08-085r. S2CID 128969768.

References

- Adams, D. A. (1977), Trinacromerum bonneri, a new polycotylid plesiosaur from the Pierre Shale of South Dakota and Wyoming, Unpublished Masters thesis, University of Kansas, 97 pages

- Adams, D. A. (1997). "Trinacromerum bonneri, new species, last and fastest pliosaur of the Western Interior Seaway". Texas Journal of Science. 49 (3): 179–198.

- Albright III, L. B.; Gillette, D. D.; Titus, A. L. (2007b). "Plesiosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) Tropic Shale of southern Utah, part 2: polycotylidae" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[41:PFTUCC]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130268187. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28.

- Bonner, O. W. (1964), An osteological study of Nyctosaurus and Trinacromerum with a description of a new species of Nyctosaurus, Unpub. Masters Thesis, Fort Hays State University, 63 pages

- Carpenter, K. (1996). "A Review of short-necked plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior, North America" (PDF). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 201 (2): 259–287. doi:10.1127/njgpa/201/1996/259.

- Everhart, M. J. (2003). "First records of plesiosaur remains in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk Member (Upper Coniacian) of the Niobrara Formation in western Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 106 (3–4): 139–148. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2003)106[0139:FROPRI]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86541758.

- Everhart, M. J. (2004a). "Plesiosaurs as the food of mosasaurs; new data on the stomach contents of a Tylosaurus proriger (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas". The Mosasaur. 7: 41–46.

- Everhart, M. J. (2004b). "New data regarding the skull of Dolichorhynchops osborni (Plesiosauroidea: Polycotylidae) from rediscovered photos of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology specimen". Paludicola. 4 (3): 74–80.

- Everhart, M. J. (2005). Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press.

- Everhart, M.J.; Decker, R.; Decker, P. (2006). "Earliest remains of Dolichorhynchops osborni (Plesiosauria: Polycotylidae) from the basal Fort Hays Limestone, Jewell County, Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 109 (3–4): 261. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2006)109[247:AOTTAM]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 198152472. (abstract)

- Everhart, M. J. (2007). Sea Monsters: Prehistoric Creatures of the Deep. ISBN 978-1-4262-0085-4.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - O'Keefe, F. R. (2004). "On the cranial anatomy of the polycotylid plesiosaurs, including new material of Polycotylus latipinnis Cope, from Alabama". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 326–340. doi:10.1671/1944. S2CID 46424292.

- Sato, T. (2005). "A new Polycotylid Plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Upper Cretaceous Bearpaw Formation in Saskatchewan, Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (5): 969–980. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[0969:ANPPRS]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 131128997.

- Schmeisser McKean, Rebecca (2011). "A new species of polycotylid plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Turonian of Utah: extending the stratigraphic range of Dolichorhynchops". Cretaceous Research. 34: 184–199. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.10.017.

- Sternberg, C. H. (1922). "Explorations of the Permian of Texas and the chalk of Kansas, 1918". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 30 (1): 119–120. doi:10.2307/3624047. JSTOR 3624047.

- Sternberg, G. F.; Walker, M. V. (1957). "Report on a plesiosaur skeleton from western Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 60 (1): 86–87. doi:10.2307/3627008. JSTOR 3627008.

- Williston, S. W. (1902). "Restoration of Dolichorhynchops osborni, a new Cretaceous plesiosaur". Kansas University Science Bulletin. 1 (9): 241–244.

- Williston, S. W. (1903). "North American plesiosaurs". Field Columbian Museum, Pub. 73. Geological Series. 2 (1): 1–79.

.png.webp)