Dolores Veintimilla

Dolores Veintimilla de Galindo (1829 in Quito – May 23, 1857, in Cuenca) was an Ecuadorian poet.

Dolores Veintimilla | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Dolores Veintimilla | |

| Born | 1829 Quito, Ecuador |

| Died | May 23, 1857 (aged 27) Cuenca, Ecuador |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Nationality | Ecuadorian |

| Spouse | Dr. Sixto Antonio Galindo y Oroña |

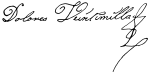

| Signature | |

| |

Her most well-known poem is "Quejas" (Complaints).

Veintemilla left few works, which were published posthumously in a collection by Celiano Monge in Quito.

Biography

Her parents were José Veintimilla and Jerónima Carrión y Antepara, who were from Loja, Ecuador.

On February 16, 1847, at the age of 18, she married Dr. Sixto Antonio Galindo y Oroña from Colombia. They had a son named Santiago, whose godmother was Rosa Ascázubi, the first lady of Ecuador (married to President Gabriel García Moreno). Veintimilla, her husband, and son moved to Guayaquil where they were accepted by high society with open arms.

A few years later, her husband left, moving to Central America to continue his studies, leaving Veintimilla alone. She occupied her time by pursuing literature and engaging with authors in the area. [1]

After watching the shooting of a friend from the indigenous community in Guayaquil, Veintimilla wrote Necrologia, a work criticizing the death penalty and treatment of indigenous people at the time.[1] The controversial opinions she espoused led members of the literary community like Fray Vicente Solano to disparage her, calling her immoral and anti-Christian for refusing to acknowledge the Christian God and instead citing a spirit she called El Gran Todo (The Great Everything). [2]

As a result, her reputation was ruined to the point that she couldn’t leave the house, and she committed suicide on May 23, 1857, in Cuenca. [1]

Literary works

Her notable prose includes “Fantasía” (Fantasy) and “Recuerdos” (Recollections), in which she dialogues with the past and blames time for giving an early death to her dreams. She best expressed her pain in her poetry, which includes “Aspiración” (Aspiration), “Desencanto” (Disenchantment), “Anhelo” (Yearning), “Sufrimiento” (Suffering), “La noche y mi dolor” (The Night and My Pain), “Quejas” (Complaints), “A mis enemigos” (To My Enemies), “A un Reloj” (To a Clock) and “A mi madre” (To My Mother). Her literary style is characterized by rhythmic and musical verse, and she hardly made use of metaphors or imagery in her poetry.[3]