Carlos, Prince of Asturias

Carlos, Prince of Asturias, also known as Don Carlos (8 July 1545 – 24 July 1568), was the eldest son and heir apparent of King Philip II of Spain. His mother was Maria Manuela of Portugal, daughter of John III of Portugal. Carlos was known to be mentally unstable and was imprisoned by his father in early 1568, dying after half a year of solitary confinement. His imprisonment and death were utilized in Spain's Black Legend. His life inspired the play Don Carlos by Friedrich Schiller and the opera Don Carlos by Giuseppe Verdi.

| Carlos | |

|---|---|

| Prince of Asturias | |

Portrait by Alonso Sánchez Coello, 1564 | |

| Born | 8 July 1545 Valladolid, Crown of Castile |

| Died | 24 July 1568 (aged 23) Madrid, Crown of Castile |

| Burial | |

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Philip II of Spain |

| Mother | Maria Manuela, Princess of Portugal |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Life

Carlos was born in Valladolid, Spain on 8 July 1545 to double first cousins Philip of Spain and María Manuela of Portugal. His paternal grandfather, Emperor Charles V, was the reigning king of Spain. Carlos's mother Maria died four days after the birth of her son from a hemorrhage she had following the birth.[1]

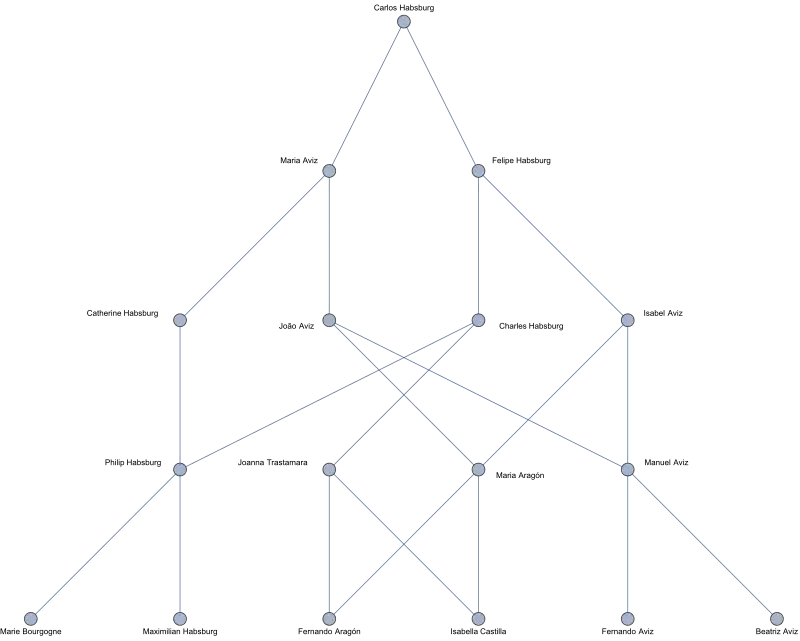

Carlos was born with unequal leg length and lordosis, resulting in his shoulders and stance being asymmetrical.[2] His physical abnormalities and behavioral issues are attributed to inbreeding as he was a member of the House of Habsburg and the House of Aviz. Carlos had only four great-grandparents instead of the typical eight,[3][4] and his parents had the same coefficient of relationship, 25%, which is equivalent to them being half siblings. He also had only six great-great-grandparents, instead of the maximum 16;[3] his maternal grandmother and his paternal grandfather were siblings, his maternal grandfather and his paternal grandmother were also siblings, and his two great-grandmothers were sisters.

Early years

Due to the death of his mother, Carlos was raised by his paternal aunts. According to the courtesan Gramiz, Carlos was spoiled, emotionally unstable, and not very bright. He was educated in the Universidad de Alcalá de Henares along with Juan of Austria and Alexander Farnese.

Carlos began exhibiting violent behavior at a young age. The Venetian ambassador, Hieronymo Soranzo, thought that Carlos was "ugly and repulsive" and once tried to force a shoemaker to eat shoes Carlos had found unsatisfactory. Another Venetian, Paolo Tiepolo, wrote: "He [Prince Carlos] wished neither to study nor to take physical exercise, but only to harm others."[5]

It is unclear if he had any intellectual disabilities, or if his intellectual ability was impaired from the 1562 brain injury.[6]

In 1556, Emperor Charles V abdicated and retired to the Monastery of Yuste in southern Spain, leaving the Spanish holdings of his empire to his son, Philip, Carlos's father. In 1559, Carlos became engaged to Elizabeth of Valois, eldest daughter of King Henry II of France. However, due to political reasons and Carlos unstable mental state, she instead married his father, King Philip, in 1560.

At age 14 he fell ill with malaria[2] and moved to Alcalá de Henares. Doctors recommended the move since the climate was milder in Alcalá de Henares. Carlos constantly complained about his father's resistance to giving him positions of authority. Finally, the King gave him a position in the Council of Castile and another in the Council of Aragon. This only made Carlos more furious, since both organisations were important but ultimately consultative. He showed no interest in the councils or in familiarising himself with political matters through them.[7]

Inheritance and head injury

Three other brides were then suggested for the Prince: Mary, Queen of Scots; Margaret of Valois, youngest daughter of Henry II of France; and Anna of Austria, who was later to become Philip's fourth wife, and was a daughter of Philip's cousin, Emperor Maximilian II and Philip's sister Maria. It was agreed in 1564 that Carlos should marry Anna.[8] His father promised him rule over the Low Countries in 1559, before his accident, but Carlos's growing mental instability after it, along with his demonstrations of sadism, made his father hesitate and ultimately change his mind, which enraged Carlos further.[9]

The 15-year-old Carlos was recognised in 1560 as the heir-apparent to the Castilian throne, and three years later as heir-apparent to the Crown of Aragon as well. Also, had he lived until the onset of the Portuguese succession crisis two decades later, he would have had a better claim to the Portuguese throne (in the aftermath of the extinction of the House of Aviz) than his father as he was the eldest surviving grandson of King John III of Portugal. Because of his eminence, he often attended meetings of the Council of State (which dealt with foreign affairs) and was in correspondence with his aunt Margaret, who governed the Low Countries in his father's name.[10]

In 1562, he sustained a serious head injury falling down stairs while chasing a serving girl. The prince was close to death, in terrible pain and experiencing delusions.[2] After trying all sorts of remedies, including doctors of all types, healers, and even the relics of Diego de Alcalá, his life was saved by a trepanation of the skull, performed by the eminent anatomist Andreas Vesalius.[11][2] After his recovery, Carlos became even wilder, more unstable in his temper and unpredictable in his behaviour.[2] His father was forced to move him away from any position of power.[9] He took a dislike to the Duke of Alba, who became the commander of Philip's forces in the Netherlands, a position that had been promised to Carlos.

Insanity, treason and attempted patricide

His frustration and mental problems were useful for the rebel factions in the Low Countries. In 1565, Carlos made contacts with a representative of Count Egmont and Philip of Montmorency, from the Low Countries, who were among the leaders of the revolt against Philip. He planned on fleeing to the Netherlands and declaring himself king, with the support of the rebels. In one of his chaotic actions he confessed the plot to Ruy Gómez de Silva, Prince of Eboli, who loyally informed the king.

In 1566, Floris of Montmorency established new contacts with him in the name of Count Egmont and Philip of Montmorency, to repeat the previous plot.

In 1567, Carlos ordered a house to be set on fire after he was accidentally splashed with water being thrown from the house's window. He also attempted to murder the Duke of Alba, a servant, and a guard in that same year.[12]

In the autumn of 1567, he made another attempt to flee to the Netherlands by asking John of Austria to take him to Italy. John asked for 24 hours to make his decision, during which he revealed Carlos's plan to Phillip who immediately denied permission for the trip.[13]

After being denied Carlos attempted to shoot John of Austria. A servant had unloaded Carlos's gun while he lured John into his room. After Carlos discovered his gun was unloaded, he attacked John with bare hands. After hearing about the attack, Philip ordered that Carlos be confined in his room without contact to the outside world.[12]

Just before midnight on 17 January 1568, Philip II, in armour, and with four councillors, entered Don Carlos' bedchamber in the Alcázar of Madrid where they declared his arrest, seized his papers and weapons, and nailed up the windows.[2][14] Carlos threatened suicide, which then caused him to be banned from having knives or forks in his room. Carlos then tried to starve himself, but this also failed.

Death

When it came to explaining the situation to public opinion and European courts, Philip tried to explain his son's absence without disclosing his actual faults or mental condition, in hopes of an eventual recovery. This lack of transparency was used to fuel the anti-Imperial propaganda of William the Silent. On 24 July 1568, the prince died in his room, probably as the result of his delicate health. His death was used as one of the core elements of the Spanish Black Legend in the Netherlands, which needed to justify a revolt against the king, which subsequently caused The Eighty Years' War. It was later claimed that he was poisoned on the orders of King Philip, especially by William in his Apology, a 1581 propaganda work against the Spanish king.[15] The idea of the poisoning had been held by central and north European historians, based on the pieces of propaganda produced in the Netherlands, until the 20th century, while most Spanish and Italian historians kept claiming that evidence and documentation pointed at a death by natural causes.[16][2] Modern historians now think that Don Carlos died of natural causes. Carlos grew very thin, and some had interpreted his hunger strikes as an eating disorder developed during his imprisonment, alternating self-starvation with heavy binges.[17]

Legend and literature

.svg.png.webp)

The idea of King Philip confining and murdering his own son later played a minor role in establishing the anti-Spanish Black Legend[15][2] in England, and a major one in forming it in the Netherlands, Germany and central Europe.[18][19] The propaganda created from it formed the basis for Friedrich Schiller's 1787 tragedy Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien.

Schiller based his work on a novel written in 1672 by the French Abbé, César Vichard de Saint-Réal, which was also the source used by the English writer Thomas Otway for his play Don Carlos, Prince of Spain. In both works, romantic tragedies that combine nationalism and romantic love, Carlos incarnates the ideal of the romantic knight, noble and brave. He is presented as the lover of young Elizabeth of Valois, Philip's wife, as they both fight for freedom and for their love against a cruel, despotic, merciless, and far-too-old-for-Isabel Philip II and his court of equally cruel and despotic Spaniards. Finally, the hero is defeated by treason due to his excess of nobility.[20]

Schiller's play was adapted into several operas, most notably Giuseppe Verdi's Don Carlos (1867, also known under its Italian title, Don Carlo). Verdi's opera is probably the version of the story most familiar to modern audiences, as it is a mainstay of the operatic repertoire and is still frequently performed. In it, Carlos is portrayed sympathetically as a victim of court intrigues, and little reference is made to his mental instability or violent tendencies.

The story of a king jailing his own son is also the basis for the Spanish play La vida es sueño (Life Is a Dream) (1635), by Pedro Calderón de la Barca; however, this play does not explicitly refer to Don Carlos, starts with a different premise, and was likely inspired by a combination of religious reflection and Plato's cave, in the line of Spanish Neoplatonism.[21]

In popular media

The role of Carlos is portrayed by Canadian actor Mark Ghanimé in the CW show Reign.[22] He was portrayed as a sexual deviant, who enjoyed being whipped, and showed interest in ruling Scotland with a crown matrimonial. Reign does hold true to the facts of brain damage, but instead of a fall, Don Carlos's head is impaled by a piece of wood from his "sex horse".

Carlos is portrayed by Joseph Cuby as a 14 year old sadist betrothed to Princess Mariella (Francesca Annis) in the TV series Sir Francis Drake (1962) episode "Visit to Spain".

In Foxe's Book of Martyrs

John Foxe, in Actes and Monuments, better known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs (2nd ed., 1570), wrote the following about Carlos:

One prince, indeed, intended to abolish the inquisition, but he lost his life before he became king, and consequently before he had the power so to do; for the very intimation of his design procured his destruction.

This was that amiable prince Don Carlos, son of Philip the Second, king of Spain, and grandson of the celebrated emperor Charles V. Don Carlos, possessed all the good qualities of his grandfather without any of the bad ones of his father; and was a prince of great vivacity, admirable learning, and the most amiable disposition.—He had sense enough to see into the errors of popery, and abhorred the very name of the inquisition. He inveighed publicly against the institution, ridiculed the affected piety of the inquisitors, did all he could to expose their atrocious deeds, end even declared, that if he ever came to the crown, he would abolish the inquisition, and exterminate its agents. These things were sufficient to irritate the inquisitors against the prince: they, accordingly, bent their minds to vengeance, and determined on his destruction. The inquisitors now employed all their agents and emissaries to spread abroad the most artful insinuations against the prince; and, at length, raised such a spirit of discontent among the people, that the king was under the necessity of removing Don Carlos from court. Not content with this, they pursued even his friends, and obliged the king likewise to banish Don John, duke of Austria, his own brother, and consequently uncle to the prince; together with the prince of Parma, nephew to the king, and cousin to the prince, because they well knew that both the duke of Austria, and the prince of Parma, had a most sincere and inviolable attachment to Don Carlos. Some few years after, the prince having shown great lenity and favour to the protestants in the Netherlands, the inquisition loudly exclaimed against him, declaring, that as the persons in question were heretics, the prince himself must necessarily be one, since he gave them countenance. In short, they gained so great an ascendency over the mind of the king, who was absolutely a slave to superstition, that, shocking to relate, he sacrificed the feelings of nature to the force of bigotry, and, for fear of incurring the anger of the inquisition, gave up his only son, passing the sentence of death on him himself.

The prince, indeed, had what was termed an indulgence; that is, he was permitted to choose the manner of his death. Roman like, the unfortunate young hero chose bleeding and the hot bath; when the veins of his arms and legs being opened, he expired gradually, falling a martyr to the malice of the inquisitors, and the stupid bigotry of his father.[23]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Carlos, Prince of Asturias | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Kamen p. 20

- Martínez-Lage, Juan F.; Piqueras-Pérez, Claudio (1 July 2015). "Brief account on the head injury of a noble youngster in the sixteenth century (Prince Don Carlos, heir to Philip II of Spain, 1545–1568)". Child's Nervous System. 31 (7): 1005–1008. doi:10.1007/s00381-015-2693-7. ISSN 1433-0350. PMID 25837577.

- Parker p. 87

- See also: Theodorou, K; Couvet, D (2006). "On the expected relationship between inbreeding, fitness, and extinction". Genet Sel Evol. 38 (4): 371–87. doi:10.1051/gse:2006010. PMC 2689291. PMID 16790228.; Alvarez, G; Ceballos, FC; Quinteiro, C (2009). "The role of inbreeding in the extinction of a European royal dynasty". PLOS ONE. 4 (4): e5174. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5174A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005174. PMC 2664480. PMID 19367331.

- Marshall pp. 18–19

- Gonzalo Sánchez-Molero, José Luis (2004). "Lectura y bibliofilia en el príncipe don Carlos (1545–1568), o la alucinada búsqueda de la 'sabiduría'". La memoria de los libros. Estudios sobre la historia del escrito y de la lectura en Europa y América Tomo I (Instituto de Historia del Libro y de la Lectura): 705–734.

- Relación del doctor Dionisio Daza Chacón sobre la herida de cabeza del príncipe Carlos; CODOIN, vol.XVIII, pags. 537–563

- Kamen p. 120

- Pérez, Joseph. «El Príncipe Don Carlos, un problema de Estado para Felipe II», Conferencia extraordinaria en la XXVIII edición de los Cursos de Verano de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, a cargo de Joseph Pérez, Premio Príncipe de Asturias de Ciencias Sociales 2014, 22 de julio de 2015

- Parker p. 89

- Parker p. 88

- Parker, Geoffrey (2002). Philip II. Open Court, pp. 92–93, 101. 4ª edición. ISBN 978-0-8126-9519-9.

- Parker p. 90

- Kamen p. 121; Parker pp. 90, 92

- Parker pp. 92–93, 201

- Fernández Álvarez, Manuel (2006). "1568: Annus horribilis-El príncipe don Carlos p.395-425". Felipe II y su tiempo. Madrid: Espasa Calpe. ISBN 84-670-2292-2.

- Parker p. 92

- Arnoldsson, Sverker. "La Leyenda Negra: Estudios Sobre Sus Orígines," Göteborgs Universitets Årsskrift, 66:3, 1960

- Gibson, Charles. The Black Legend: Anti-Spanish Attitudes in the Old World and the New. 1971.

- "Don Carlos". Instituto Nazionale di Studi Verdiani. Retrieved 5 November de 2010.

- José Manuel Trives Pérez, ed. (2012). "Inventario de representaciones de La vida es sueño".

- "'Reign' Season 3, Midseason Finale Spoilers: Mary Uncovers Dark Secret About Prince Don Carlos". Latin Post. 25 November 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Foxe's Book of Martyrs, Chapter V

References

- Kamen, Henry: Philip of Spain. Yale University Press. 1998. ISBN 978-0-300-07800-8

- Marshall, Peter: The Magic Circle of Rudolf II: Alchemy and Astrology in Renaissance Prague. Walker & Company. 2006. ISBN 978-0-8027-1551-7

- Parker, Geoffrey: Philip II: Fourth Edition. Open Court. 2002. ISBN 978-0-8126-9519-9

- Parker, Geoffrey: Imprudent King: A New Life of Philip II. Yale University Press. 2014. ISBN 978-0-300-196535

External links

- Radiolab's program A Clockwork Miracle