Revolver

A revolver is a repeating handgun that has at least one barrel and uses a revolving cylinder containing multiple chambers (each holding a single cartridge) for firing. Because most revolver models hold up to six cartridges, before needing to be reloaded, revolvers are commonly called six shooters.[1][2]

Before firing, cocking the revolver's hammer partially rotates the cylinder, indexing one of the cylinder chambers into alignment with the barrel, allowing the bullet to be fired through the bore. The hammer cocking in nearly all revolvers are manually driven, and can be achieved either by the user using the thumb to directly pull back the hammer (as in single-action), via internal linkage relaying the force of the trigger-pull (as in double-action), or both (as in double-action/single-action). By sequentially rotating through each chamber, the revolver allows the user to fire multiple times until having to reload the gun, unlike older single-shot firearms that had to be reloaded after each shot. Some rare revolver models can utilize the blowback of the preceding shot to automatically cock the hammer and index the next chamber, although these self-loading revolvers (known as automatic revolvers, despite technically being semi-automatic) never gained any widespread usage.

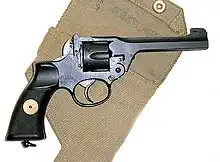

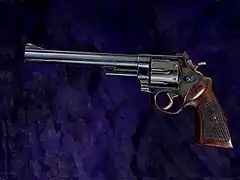

Although largely surpassed in convenience and ammunition capacity by semi-automatic pistols, revolvers still remain popular as back-up and off-duty handguns among American law enforcement officers and security guards and are still common in the American private sector as defensive, sporting, and hunting firearms. Famous revolver models include the Colt 1851 Navy Revolver, the Webley, the Colt Single Action Army, the Colt Official Police, Smith & Wesson Model 10, the Smith & Wesson Model 29 of Dirty Harry fame, the Nagant M1895, and the Colt Python.

Though the majority of weapons using a revolver mechanism are handguns, other firearms may also have a revolver action. These include some models of rifles, shotguns, grenade launchers, and autocannons. Revolver weapons differ from Gatling-style rotary weapons in that in a revolver only the chambers rotate, while in a rotary weapon there are multiple full firearm actions with their own barrels which rotate around a common ammunition feed.

History

In the development of firearms, an important limiting factor was the time required to reload the weapon after it was fired. While the user was reloading, the weapon was useless, allowing an adversary to attack the user. Several approaches to the problem of increasing the rate of fire were developed, the earliest involving multi-barrelled weapons which allowed two or more shots without reloading.[3] Later weapons featured multiple barrels revolving along a single axis.

A matchlock revolver with a single barrel and four chambers held at the Tower of London is believed to have been invented some time in the 15th century.[4] A revolving three-barrelled matchlock pistol in Venice is dated from at least 1548.[5] During the late 16th century in China, Zhao Shi-zhen invented the Xun Lei Chong, a five-barreled musket revolver spear. Around the same time, the earliest examples of the modern revolver were made in Germany. These weapons featured a single barrel with a revolving cylinder holding the powder and ball. They would soon be made by many European gun-makers, in numerous designs and configurations.[6] However, these weapons were complicated, difficult to use and prohibitively expensive to make, and thus not widely distributed.

In the early 19th century, multiple-barrel handguns called "pepper-boxes" were popular. Originally they were muzzleloaders, but in 1837, the Belgian gunsmith Mariette invented a hammerless pepperbox with a ring trigger and turn-off barrels that could be unscrewed.[7]

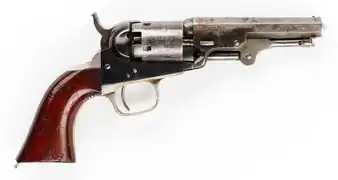

In 1836, American Samuel Colt patented a popular revolver which led to the widespread use of the revolver.[8] According to Colt, he came up with the idea for the revolver while at sea, inspired by the capstan, which had a ratchet and pawl mechanism on it, a version of which was used in his guns to rotate the cylinder by cocking the hammer. This provided a reliable and repeatable way to index each round and did away with the need to manually rotate the cylinder. Revolvers proliferated largely due to Colt's ability as a salesman, but his influence spread in other ways as well. The build quality of his company's guns became famous, and its armories in America and England trained several seminal generations of toolmakers and other machinists, who had great influence in other manufacturing efforts of the next half century.[9]

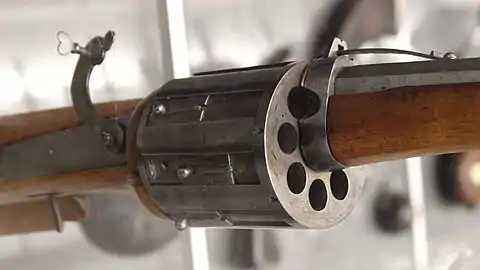

Detail of an 8-chambered matchlock revolver (Germany, c. 1580)

Detail of an 8-chambered matchlock revolver (Germany, c. 1580) Colt Paterson 2nd belt model

Colt Paterson 2nd belt model

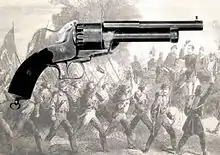

Early revolvers were caplock muzzleloaders: the user had to pour black powder into each chamber, rammed down a bullet on top of it, then placed a percussion cap on the nipple at the rear of each chamber, where the hammer would fall on it and ignite the powder charge. This was similar to loading a traditional single-shot muzzle-loading pistol, except that the powder and shot could be loaded directly into the front of the cylinder rather than having to be loaded down the whole length of the barrel. Importantly, this allowed the barrel itself to be rifled, since the user was not required to force the tight-fitting bullet down the barrel in order to load it (a traditional muzzle-loading pistol had a smoothbore barrel and the shot was relatively loose-fitting, which allowed easy loading, but was much less accurate). After firing a shot, the user would raise their pistol vertically while cocking the hammer back for their next shot, so the fragments of the burst percussion cap would fall clear of the weapon and not jam the mechanism. Some of the most popular cap-and-ball revolvers were the Colt Model 1851 "Navy" model, 1860 "Army" model, and Colt Pocket Percussion Revolvers, all of which saw extensive use in the American Civil War. Although American revolvers were the most common, European arms makers were making numerous revolvers by that time as well, many of which found their way into the hands of the American forces. These included the single-action Lefaucheux and LeMat revolvers, as well as the Beaumont–Adams and Tranter revolvers—early double-action weapons in spite of being muzzle-loaders.[10]

In 1854, Eugene Lefaucheux introduced the Lefaucheux Model 1854, the first revolver to use self-contained metallic cartridges rather than loose powder, pistol ball, and percussion caps. It is a single-action, pinfire revolver holding six rounds.[11]

On November 17, 1856, Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson signed an agreement for the exclusive use of the Rollin White Patent at a rate of 25 cents for every revolver. Smith & Wesson began production late in 1857, and enjoyed years of exclusive production of rear-loading cartridge revolvers in America due to their association with Rollin White, who held the patent[12] and vigorously defended it against any perceived infringement by other manufacturers (much as Colt had done with his original patent on the revolver). Although White held the patent, other manufacturers were able to sell firearms using the design, provided they were willing to pay royalties.[13][14]

After White's patent expired in April 1869, a third extension was refused. Other gun-makers were then allowed to produce their own weapons using the rear-loading method, without having to pay a royalty on each gun sold. Early guns were often conversions of earlier cap-and-ball revolvers, modified to accept metallic cartridges loaded from the rear, but later models, such as the Colt Model 1872 "open top" and the Smith & Wesson Model 3, were designed from the start as cartridge revolvers.[13]

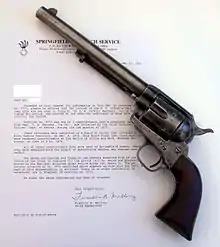

In 1873, Colt introduced the famous Model 1873, also known as the Single Action Army, the "Colt .45" (not to be confused with Colt-made models of the M1911 semi-automatic), also referred to as "the Peacemaker", one of the most famous handguns ever made.[15] This popular design, which was a culmination of many of the advances introduced in earlier weapons, fired 6 metallic cartridges and was offered in over 30 different calibers and various barrel lengths. It is still in production, along with numerous clones and lookalikes, and its overall appearance has remained the same since 1873. Although originally made for the United States Army, the Model 1873 was widely distributed and popular with civilians, ranchers, lawmen, and outlaws alike. Its design has influenced countless other revolvers. Colt has discontinued its production twice, but resumed production due to popular demand.

In the U.S., the single-action revolver remained more popular than the double-action revolver until the late 19th century. In Europe, however, arms makers were quick to adopt the double-action trigger. While the U.S. was producing weapons like the Model 1873, European manufacturers were building double-action models like the French MAS Modèle 1873 and the later British Enfield Mk I and II revolvers. (Britain relied on cartridge conversions of the earlier Beaumont–Adams double-action prior to this.) Colt's first attempt at a double action revolver to compete with European manufacturers was the Colt Model 1877, which earned lasting notoriety for its complex, expensive, and fragile trigger mechanism, which in addition to failing frequently, also had a heavy trigger pull.

In 1889, Colt introduced the Model 1889, the first double action revolver with a "swing-out" cylinder, as opposed to a "top-break" or "side-loading" cylinder. Swing-out cylinders quickly caught on, because they combined the best features of earlier designs. Top-break actions had the ability to eject all empty shells simultaneously and exposed all chambers for easy reloading, but having the frame hinged into two halves weakened the gun and negatively affected accuracy due to the lack of rigidity. "Side-loaders", like the earlier Colt Model 1871 and 1873, had a rigid frame, but required the user to eject and load one chamber at a time as they rotated the cylinder to line each chamber up with the side-mounted loading gate.[16] Smith & Wesson followed seven years later with the Hand Ejector, Model 1896 in .32 S&W Long caliber, followed by the very similar, yet improved, Model 1899 (later known as the Model 10), which introduced the new .38 Special cartridge. The Model 10 went on to become the best selling handgun of the 20th century, at 6,000,000 units, and the .38 Special is still the most popular chambering for revolvers in the world. These new guns were an improvement over the Colt 1889 design since they incorporated a combined center-pin and ejector rod to lock the cylinder in position, whereas the Colt 1889 did not use a center pin and the cylinder was prone to move out of alignment.[16]

Revolvers have remained popular in many areas, although for law enforcement and military personnel, they have largely been supplanted by magazine-fed semi-automatic pistols, such as the Beretta M9 and the SIG Sauer M17, especially in circumstances where faster reload times and higher cartridge capacity are important.[17]

Patents

In 1815, (sometimes incorrectly dated as 1825) a French inventor called Julien Leroy patented a flintlock and percussion revolving rifle with a mechanically indexed cylinder and a priming magazine.[18][19]

Elisha Collier of Boston, Massachusetts, patented a flintlock revolver in Britain in 1818, and significant numbers were being produced in London by 1822.[20] The origination of this invention is in doubt, as similar designs were patented in the same year by Artemus Wheeler in the United States, and by Cornelius Coolidge in France.[21] Samuel Colt submitted a British patent for his revolver in 1835 and a U.S. patent (number 138) on February 25, 1836, for a Revolving gun, and made the first production model on March 5 of that year.[22]

Another revolver patent was issued to Samuel Colt on August 29, 1839. The February 25, 1836, patent was then reissued as U.S. Patent RE00124 entitled Revolving gun on October 24, 1848. This was followed by U.S. Patent 0,007,613 on September 3, 1850, for a Revolver, and by U.S. Patent 0,007,629 on September 10, 1850, for a Revolver. In 1855, Rollin White patented the bored-through cylinder entitled Improvement in revolving fire-arms U.S. Patent 00,093,653. In 1856, Horace Smith & Daniel Wesson formed a partnership (S&W), then developed and manufactured a revolver chambered for a self-contained metallic cartridge.[23] In 1993, U.S. Patent 5,333,531 was issued to Roger C. Field for an economical device for minimizing the flash gap of a revolver between the barrel and the cylinder.

Design

A revolver has several firing chambers arranged in a circle in a cylindrical block; one at a time, these chambers are brought into alignment with the firing mechanism and barrel. In contrast, other repeating firearms, such as bolt-action, lever-action, pump-action, and semi-automatic, have a single firing chamber and a mechanism to load and extract cartridges into it.[24]

A single-action revolver requires the hammer to be pulled back by hand before each shot, which also revolves the cylinder. This leaves the trigger with one "single action" to perform—releasing the hammer to fire the shot. In contrast, with a self-cocking, or double-action, revolver, one long squeeze of the trigger pulls back the hammer and revolves the cylinder, then finally fires the shot, thus requiring more force and distance to pull the trigger than in a single-action revolver. They can generally be fired faster than a single-action, but with reduced accuracy in the hands of most shooters.[24]

Most modern revolvers are "traditional double-action", which means they may operate either in single-action or self-cocking mode. The accepted meaning of "double-action" has come to be the same as "self-cocking", so modern revolvers that cannot be pre-cocked are called "double-action-only".[24] These are intended for concealed carry, because the hammer of a traditional design is prone to snagging on clothes when drawn. Most revolvers do not come with accessory rails, which are used for mounting lights and lasers, except for the Smith & Wesson M&P R8 (.357 Magnum),[25] Smith & Wesson Model 325 Thunder Ranch (.45 ACP),[26] and all versions of the Chiappa Rhino (.357 Magnum, 9×19mm, .40 S&W, or 9×21mm) except for the 2" and 3" models, respectively.[27] However, certain revolvers, such as the Taurus Judge and Charter Arms revolvers, can be fitted with accessory rails.[28]

Revolvers most commonly have 6 chambers, hence the common names of "six-gun" or "six-shooter".[29] However, some revolvers have more or less than 6, depending on the size of the gun and caliber of the bullet. Each chamber has to be reloaded manually, which makes reloading a revolver a much slower procedure than reloading a semi-automatic pistol.[29]

Compared to autoloading handguns, a revolver is often much simpler to operate and may have greater reliability.[29] For example, should a semiautomatic pistol fail to fire, clearing the chamber requires manually cycling the action to remove the errant round, as cycling the action normally depends on the energy of a cartridge firing.[29] With a revolver, this is not necessary as none of the energy for cycling the revolver comes from the firing of the cartridge, but is instead supplied by the user either through cocking the hammer or, in a double-action design, by just squeezing the trigger.[29] Another significant advantage of revolvers is superior ergonomics, particularly for users with small hands.[29] A revolver's grip does not hold a magazine, and it can be designed or customized much more than the grip of a typical semi-automatic.[29] Partially because of these reasons, revolvers still hold significant market share as concealed carry and home-defense weapons.[29]

A revolver can be kept loaded and ready to fire without fatiguing any springs and is not very dependent on lubrication for proper firing.[29] Additionally, in the case of double-action-only revolvers there is no risk of accidental discharge from dropping alone, as the hammer is cocked by the trigger pull.[29] However, the revolver's clockwork-like internal parts are relatively delicate and can become misaligned after a severe impact, and its revolving cylinder can become jammed by excessive dirt or debris.[29]

Over the long period of development of the revolver, many calibers have been used.[30] Some of these have proved more durable during periods of standardization and some have entered general public awareness. Among these are the .22 Long Rifle, a caliber popular for target shooting and teaching novice shooters; .38 Special and .357 Magnum, known for police use; the .44 Magnum, famous from Clint Eastwood's Dirty Harry films; and the .45 Colt, used in the Colt revolver of the Wild West. Introduced in 2003, the Smith & Wesson Model 500 is one of the most powerful revolvers, utilizing the .500 S&W Magnum cartridge.[31]

Because the rounds in a revolver are headspaced on the rim, some revolvers are capable of chambering more than one type of ammunition. Revolvers chambered in .44 Magnum will also chamber .44 Special and .44 Russian, likewise revolvers in .357 Magnum will safely chamber .38 Special, .38 Long Colt, and .38 Short Colt, and revolvers in .22 WMR will safely chamber .22 Long Rifle, .22 Long, and .22 Short. In 1996, the Medusa Model 47 was made with the ability to chamber 25 different cartridges with bullet diameters between .355" and .357".[32]

Revolver technology is also present in other weapons used by the U.S. military. Some autocannons and grenade launchers use mechanisms similar to revolvers, and some riot shotguns use spring-loaded cylinders holding up to 12 rounds.[33] In addition to serving as backup guns, revolvers still fill the specialized role as a shield gun; law enforcement personnel using a "bulletproof" gun shield sometimes opt for a revolver instead of a self-loading pistol, because the slide of a pistol may strike the front of the shield when fired. Revolvers do not suffer from this disadvantage. A second revolver may be secured behind the shield to provide a quick means of continuity of fire. Many police also still use revolvers as their duty weapon due to their relative mechanical simplicity and ease of use.[34]

In 2010, major revolver manufacturers started producing polymer frame revolvers like the Ruger LCR, Smith & Wesson Bodyguard 38, and Taurus Protector Polymer. The new design incorporates polymer technology that lowers weight significantly, helps absorb recoil, and is strong enough to handle .38 Special +P and .357 Magnum loads. The polymer is only used on the lower frame and is joined to an upper frame, barrel, and cylinder that are made of metal alloy. Polymer technology is considered one of the major advancements in revolver history because the frame was previously always metal alloy and mostly a one-piece design.[35]

Another 21st century development in revolver technology is the Chiappa Rhino, a revolver introduced by Italian manufacturer Chiappa in 2009, and first sold in the U.S. in 2010. The Rhino, built with the U.S. concealed carry market in mind, is designed so that the bullet fires from the bottom chamber of the cylinder instead of the top chamber, as is typical in revolvers. This is intended to reduce muzzle flip, allowing for faster and more accurate repeat shots. In addition, the cylinder cross-section is hexagonal instead of circular, further reducing the weapon's profile.[27]

Loading and unloading

Front-loading cylinder

The first revolvers were front loading (also referred to as muzzleloading), and were similar to muskets in that the powder and bullet were loaded separately. These were caplocks or "cap and ball" revolvers, because the caplock method of priming was the first to be compact enough to make a practical revolver feasible. When loading, each chamber in the cylinder was rotated out of line with the barrel, and charged from the front with loose powder and an oversized bullet. Next, the chamber was aligned using the ramming lever underneath the barrel. Pulling the lever would drive a rammer into the chamber, pushing the ball securely in place. Finally, the user would place percussion caps on the nipples on the rear face of the cylinder.[10]

After each shot, a user was advised to raise his revolver vertically while cocking back the hammer so as to allow the fragments of the spent percussion cap to fall out safely. Otherwise, the fragments could fall into the revolver's mechanism and jam it. Caplock revolvers were vulnerable to "chain fires", wherein hot gas from a shot ignited the powder in the other chambers. This could be prevented by sealing the chambers with cotton, wax, or grease. Chain fire led to the shots hitting the shooters hand, which is one of the main reasons why revolver rifles were uncommon. By the time metallic cartridges became common, more effective mechanisms for a repeating rifle, such as lever-action, had been developed.[36]

Loading a cylinder in this manner was a slow and awkward process and generally could not be done in the midst of battle.[37] Some soldiers avoided this by carrying multiple revolvers in the field. Another solution was to use a revolver with a detachable cylinder design. These revolvers allowed the shooter to quickly remove a cylinder and replace it with a full one.[24]

Colt 1851 Navy with powder flask

Colt 1851 Navy with powder flask Front reloading a cap and ball pistol

Front reloading a cap and ball pistol

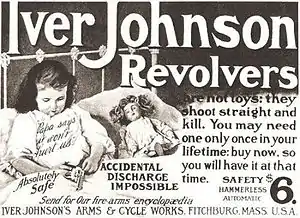

Fixed cylinder designs

In many of the first generation of cartridge revolvers (especially those that were converted after manufacture), the base pin on which the cylinder revolved was removed, and the cylinder taken out from the revolver for loading. Most revolvers using this method of loading are single-action revolvers, although Iver Johnson produced double-action models with removable cylinders. The removable-cylinder design is employed in some modern "micro-revolvers" (usually chambered in .22 rimfire and small enough to fit in the palm of the hand) to simplify their design.[35]

Later single-action revolver models with a fixed cylinder used a loading gate at the rear of the cylinder that allowed insertion of one cartridge at a time for loading, while a rod under the barrel could be pressed rearward to eject a fired case.[38]

The loading gate on the original Colt designs (and on nearly all single-action revolvers since, such as the famous Colt Single Action Army) is on the right side, which was done to facilitate loading while on horseback; with the revolver held in the left hand with the reins of the horse, the cartridges can be ejected and loaded with the right hand.[39]

Because the cylinders in these types of revolvers are firmly attached at the front and rear of the frame, and the frame is typically full thickness all the way around, fixed cylinder revolvers are inherently strong designs. Accordingly, many modern large caliber hunting revolvers tend to be based on the fixed cylinder design. Fixed cylinder revolvers can fire the strongest and most powerful cartridges, but at the price of being the slowest to load or unload since they cannot use speedloaders or moon clips to load multiple cartridges at once, as only one chamber is exposed at a time to the loading gate.[40]

Top-break cylinder

In a top-break revolver, the frame is hinged at the bottom front of the cylinder. Releasing the lock and pushing the barrel down exposes the rear face of the cylinder. In most top-break revolvers, this act also operates an extractor that pushes the cartridges in the chambers back far enough that they will fall free, or can be removed easily. Fresh rounds are then inserted into the cylinder. The barrel and cylinder are then rotated back and locked in place, and the revolver is ready to fire.[24]

Top-break revolvers are able to be loaded more rapidly than fixed frame revolvers, especially with the aid of a speedloader or moon clip. However, this design is much weaker and cannot handle high pressure rounds. While this design has become mostly obsolete, supplanted by the stronger yet equally convenient swing-out cylinder design, manufacturers still make reproductions of late 19th century designs for use in cowboy action shooting.[24]

The first top-break revolver was patented in France and Britain at the end of December in 1858 by Devisme.[41] The most commonly found top-break revolvers were manufactured by Smith & Wesson, Webley & Scott, Iver Johnson, Harrington & Richardson, Manhattan Fire Arms, Meriden Arms, and Forehand & Wadsworth.[42]

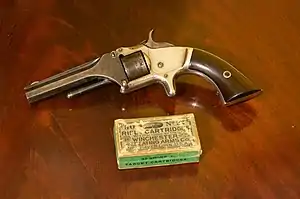

Tip-up cylinder

The tip-up revolver was the first design to be used with metallic cartridges in the Smith & Wesson Model 1, on which the barrel pivoted upwards, hinged on the forward end of the topstrap. On the S&W tip-up revolvers, the barrel release catch is located on both sides of the frame in front of the trigger. Smith & Wesson discontinued it in the third series of the Smith & Wesson Model 1 1/2 but it was fairly widely used in Europe in the 19th century after a patent by Spirlet in 1870, which also included an ejector star.[43]

Swing-out cylinder

The most modern method of loading and unloading a revolver is by means of the swing-out cylinder.[44] The first swing-out cylinder revolver was patented in France and Britain at the end of December in 1858 by Devisme.[41] The cylinder is mounted on a pivot that is parallel to the chambers, and the cylinder swings out and down (to the left in most cases). An extractor is fitted, operated by a rod projecting from the front of the cylinder assembly. When pressed, it will push all fired rounds free simultaneously (as in top-break models, the travel is designed to not completely extract longer, unfired rounds). The cylinder may then be loaded (individually or with the use of a speedloader), closed, and latched in place.[24]

The pivoting part that supports the cylinder is called the crane; it is the weak point of swing-out cylinder designs. Using the method often portrayed in movies and television of flipping the cylinder open and closed with a flick of the wrist can actually cause the crane to bend over time, throwing the cylinder out of alignment with the barrel. Lack of alignment between chamber and barrel is dangerous, as it can impede the bullet's transition from chamber to barrel. This causes higher pressures in the chamber, bullet damage, and the potential for an explosion if the bullet becomes stuck.[45]

The shock of firing can exert a great deal of stress on the crane, as in most designs the cylinder is only held closed at one point, the rear of the cylinder. Stronger designs, such as the Ruger Super Redhawk, use a lock in the crane as well as the lock at the rear of the cylinder. This latch provides a more secure bond between cylinder and frame, and allows the use of larger, more powerful cartridges. Swing-out cylinders are not as strong as fixed cylinders, and great care must be taken with the cylinder when loading, so as not to damage the crane.[45]

Other designs

One unique design was designed by Merwin Hulbert in which the barrel and cylinder assembly were rotated 90° and pulled forward to eject shells from the cylinder.

Action

Single-action

In a single-action revolver, the hammer is manually cocked, usually with the thumb of the firing or supporting hand. This action advances the cylinder to the next round and locks the cylinder in place, with the chamber aligned with the barrel. When the trigger is pulled, it releases the hammer, which fires the round in the chamber. To fire again, the hammer must be manually cocked again. This is called "single-action" because the trigger only performs a single action, of releasing the hammer. Because only a single action is performed and trigger pull is lightened, firing a revolver in this way allows most shooters to achieve greater accuracy. Additionally, the need to cock the hammer manually acts as a safety. With some revolvers, since the hammer rests on the primer or nipple, accidental discharge from impact is more likely if all 6 chambers are loaded. The Colt Paterson, Colt Walker, Colt Dragoon, and Colt Single Action Army of the American frontier era are examples of this system.[24]

Double-action

In double-action (DA), the stroke of the trigger pull generates two actions:

- The hammer is pulled back to the cocked position, which also indexes the cylinder to the next round.

- The hammer is released to strike the firing pin.

Thus, DA means that a cocking action separate from the trigger pull is unnecessary; every trigger pull will result in a complete cycle. This allows uncocked carry, while also allowing draw-and-fire using only the trigger. However, this will require a longer and harder trigger stroke, though this drawback can also be viewed as a safety feature, as the gun is safer against accidental discharges from being dropped.[24] The sole mode of operation was seen as reducing training time for the British Army in WWII where the revolver usage was rapid fire at very close ranges.[46]

Most double-action revolvers may be fired in two ways.[24]

- The first way is single-action; that is, exactly the same as a single-action revolver; the hammer is cocked with the thumb, which indexes the cylinder, and when the trigger is pulled, the hammer is released and the round is fired.

- The second way is double-action, or from a hammer-down position. In this case, the trigger first cocks the hammer and revolves the cylinder, then trips the hammer at the rear of the trigger stroke, firing the round in the chamber.

Certain revolvers, called double-action-only (DAO) or, more correctly but less commonly, self-cocking, lack the latch that enables the hammer to be locked to the rear, and thus can only be fired in the double-action mode. With no way to lock the hammer back, DAO designs tend to have bobbed or spurless hammers, and may even have the hammer completely covered by the revolver's frame (i.e., shrouded or hooded). These are generally intended for concealed carrying, as a hammer spur could snag when the revolver is drawn from clothing, but this design may result in reduction in accuracy in aimed fire.[47]

DA and DAO revolvers were the standard-issue sidearm of many police departments for many decades. Only in the 1980s and 1990s did the semiautomatic pistol gain popularity after the advent of safe actions. The reasons for these choices are the modes of carry and use. Double-action is preferred in high-stress situations because it allows a mode of carry in which one only has to draw and pull the trigger—no safety catch release nor separate cocking stroke is required.[47]

Other

In the era of cap-and-ball revolvers in the mid 19th century, two revolver models, the English Tranter and the American Savage "Figure Eight", used a method whereby the hammer was cocked by the shooter's middle finger pulling on a second trigger below the main trigger.

Iver Johnson made an unusual model from 1940 to 1947 called the Trigger Cocking Double Action. If the hammer was down, pulling the trigger would cock the hammer. If the trigger was pulled with the hammer cocked, it would then fire. This meant that to fire the revolver from a hammer down state, the trigger must be pulled twice.[48]

This is similar to the action of the "sytème Triple action" patented by Eugène Lefaucheux in French patent number 55784 on September 27, 1862 for pinfire revolvers produced in the 1860's in France. The Lefaucheux Triple Action can be used in single action by cocking the hammer with the thumb, or in double action with a long pull on the trigger, or the hammer can be cocked by a pull on the trigger, then allowing one to shoot in single action.

3D printed revolver

The Zig zag revolver is a 3D printed .38 Revolver released to the public in May 2014.[49][50] It was created by a Japanese citizen from Kawasaki named Yoshitomo Imura, using a 3D-printer and plastic filament.[50]

Use with suppressors

As a general rule, revolvers cannot be effective with a sound suppressor ("silencer"), as there is usually a small gap between the revolving cylinder and the barrel which a bullet must traverse, or jump, when fired. From this opening, a rather loud report is produced. A suppressor can only suppress noise coming from the muzzle.[51]

A suppressible revolver design does exist in the Nagant M1895, a Belgian-designed revolver used by Imperial Russia and later the Soviet Union from 1895 through World War II. This revolver uses a unique cartridge whose case extends beyond the tip of the bullet, and a cylinder that moves forward to place the end of the cartridge inside the barrel when ready to fire. This bridges the gap between the cylinder and the barrel, and the case expands to seal the gap when fired. While the tiny gap between cylinder and barrel on most revolvers is insignificant to the internal ballistics, the seal of the Nagant is especially effective when used with a suppressor, and a number of suppressed Nagant revolvers have been used since its invention.[52]

There is a modern revolver of Russian design, the OTs-38,[53] which uses ammunition that incorporates the silencing mechanism into the cartridge case, making the gap between cylinder and barrel irrelevant as far as the suppression issue is concerned. The OTs-38 does need an unusually close and precise fit between the cylinder and barrel due to the shape of bullet in the special ammunition (Soviet SP-4), which was originally designed for use in a semi-automatic.

Additionally, the U.S. military experimented with designing a special version of the Smith & Wesson Model 29 for tunnel rats, called the Quiet Special Purpose Revolver, or QSPR, that uses special .40 caliber ammunition. It never entered official service.

Automatic revolvers

The term "automatic revolver" has two different meanings, the first being used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when "automatic" referred not to the operational mechanism of firing, but to extraction and ejection of spent casings. An "automatic revolver" in this context is one which extracts empty fired cases "automatically", such as upon breaking open the action, rather than requiring manual extraction of each case individually with a sliding rod or pin (as in the Colt Single Action Army design). This term was widely used in the advertising of the period as a way to distinguish such revolvers from the far more common rod-extraction types.[54]

In the second sense, "automatic revolver" refers to the mechanism of firing rather than extraction. Double-action revolvers use a long trigger pull to cock the hammer, thus negating the need to manually cock the hammer between shots. The disadvantage of this is that the long, heavy pull cocking the hammer makes the double-action revolver much harder to shoot accurately than a single-action revolver (although cocking the hammer of a double-action reduces the length and weight of the trigger pull). A rare class of revolvers, called automatic for its firing design, attempts to overcome this restriction, giving the high speed of a double-action with the trigger effort of a single-action. The Webley-Fosbery Automatic Revolver is the most famous commercial example of this. It was recoil-operated, and the cylinder and barrel recoiled backwards to cock the hammer and revolve the cylinder. Cam grooves were milled on the outside of the cylinder to provide a means of advancing to the next chamber—half a turn as the cylinder moved back, and half a turn as it moved forward. .38 caliber versions held eight shots; .455 caliber versions held six. At the time, the few available automatic pistols were larger, less reliable, and more expensive. The automatic revolver was popular when it first came out, but was quickly superseded by the creation of reliable, inexpensive semi-automatic pistols.[55]

In 1997, the Mateba company developed a type of recoil-operated automatic revolver, commercially named the Mateba Autorevolver, which uses the recoil energy to auto-rotate a normal revolver cylinder holding six or seven cartridges, depending on the model. The company has made several versions of its Autorevolver, including longer-barrelled and carbine variations, chambered in .357 Magnum, .44 Magnum and .454 Casull.[56]

The Pancor Jackhammer is a combat shotgun based on a similar mechanism to an automatic revolver. It uses a blow-forward action to move the barrel forward (which unlocks it from the cylinder), rotate the cylinder, and cock the hammer.[57]

Revolving long guns

Revolvers were not limited to handguns; as a longer barrelled arm is more useful in military applications than a sidearm, the idea was applied to both rifles and shotguns throughout the history of the revolver mechanism with mixed degrees of success.[58]

Rifles

Revolving rifles were developed in an attempt to increase the rate of fire of rifles by combining them with the revolving firing mechanism that had been developed earlier for revolving pistols. Colt began experimenting with revolving rifles in the early 19th century, making them in a variety of calibers and barrel lengths. Colt revolving rifles were the first repeating rifles adopted by the U.S. military, issued to soldiers to improve their rate of fire. However, after firing six shots, the shooter had to take an excessive amount of time to reload. Also, on occasion, these Colt rifles discharged all their rounds at once, endangering the shooter. Even so, an early model was used in the Seminole Wars in 1838.[59][60] During the Civil War, a LeMat Carbine was made based on the LeMat revolver.[61]

Taurus and its Australian partner company, Rossi, manufactures a carbine variant of the Taurus Judge revolver known as the Taurus/Rossi Circuit Judge. It comes in the original combination chambering of .45 Long Colt and .410 bore, as well as the .44 Magnum chambering and dual-cylinder .22LR/.22WMR model. The rifle has small blast shields attached to the cylinder to protect the shooter from hot gases escaping between the cylinder and barrel.[62]

Shotguns

Colt briefly manufactured several revolving shotguns that were met with mixed success. The Colt Model 1839 Shotgun was manufactured between 1839 and 1841. Later, the Colt Model 1855 Shotgun, based on the Model 1855 revolving rifle, was manufactured between 1860 and 1863. Because of their low production numbers and age, they are among the rarest of all Colt firearms.[63]

The Armsel Striker was a modern take on the revolving shotgun that held 10 rounds of 12 Gauge ammunition in its cylinder. It was copied by Cobray as the Streetsweeper.[17][64]

As noted, the original Taurus/Rossi Circuit Judge is chambered to use both .45LC cartridges and .410 bore shells. However, it utilizes a rifled, rather than smooth-bore barrel.

The MTs255 (Russian: МЦ255) is a shotgun fed by a 5-round internal revolving cylinder. It is produced by the TsKIB SOO, Central Design, and Research Bureau of Sporting and Hunting Arms. They are available in 12, 20, 28, and 32 gauges, and .410 bore.

Other weapons

The Hawk MM-1, Milkor MGL, RG-6, and RGP-40 are grenade launchers that use a revolver action. Because the cylinders are much more massive, they use a spring-wound mechanism to index the cylinder.

Revolver cannons use a motor-driven, revolver-like mechanism to fire medium caliber ammunition.

Six gun

A six gun or six-shooter is a revolver that holds six cartridges. The cylinder in a six gun is often called a "wheel", and the six gun is itself often called a "wheel gun".[65][66] Although a "six gun" can refer to any six-chambered revolver, it is typically a reference to the Colt Single Action Army, or its modern look-alikes such as the Ruger Vaquero and Beretta Stampede.

Until the 1970s, when older-design revolvers such as the Colt Single Action Army and Ruger Blackhawk were re-engineered with drop safeties (such as firing pin blocks, hammer blocks, or transfer bars) that prevent the firing pin from contacting the cartridge's primer unless the trigger is pulled, safe carry required the hammer being positioned over an empty chamber, thus reducing the available cartridges from six to five, or, on some models, positioned in between chambers on either a pin or in a groove made for that purpose, thus keeping the full six rounds available. This kept the uncocked hammer from resting directly on the primer of a cartridge. If not used in this manner, the hammer rests directly on a primer and unintentional firing may occur if the gun is dropped or the hammer is struck. Some holster makers provided a thick leather thong to place underneath the hammer that both allowed the carry of a gun fully loaded with all six rounds and secured the gun in the holster to help prevent its accidental loss.

Six guns are commonly used by cowboy action shooting enthusiasts in competition shooting and are designed to mimic the gunfights of the Old West, as well as for other applications such as general target shooting, hunting, and personal defense.[67]

Notable brands and manufacturers

- Robert Adams

- Armscor

- Astra

- Charter Arms

- Chiappa Firearms

- Cimarron Firearms

- Colt's Manufacturing Company

- Fabrique Nationale de Herstal

- Freedom Arms

- Griswold and Gunnison

- Harrington & Richardson

- Iver Johnson

- Janz (revolvers)

- Kimber Manufacturing

- Korth

- Magnum Research

- Manurhin

- Mateba Arms

- Meriden Firearms Co.

- Merwin Hulbert

- Nagant

- North American Arms

- Remington Arms

- Rossi

- Royal Small Arms Factory

- Sturm, Ruger & Co.

- Smith & Wesson

- Taurus Firearms

- United States Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company

- A. Uberti, Srl.

- William Tranter

- Webley & Scott

- Dan Wesson Firearms

Gallery

Colt Anaconda .44 Magnum revolver

Colt Anaconda .44 Magnum revolver Colt Python .357 Magnum revolvers

Colt Python .357 Magnum revolvers

Smith & Wesson Model 625JM, as designed by Jerry Miculek.

Smith & Wesson Model 625JM, as designed by Jerry Miculek. Alfa Proj Model Alfa Para 9mm caliber

Alfa Proj Model Alfa Para 9mm caliber Taurus .357 Magnum Model 605

Taurus .357 Magnum Model 605

Colt 1849 Pocket Model, made 1850–1873.

Colt 1849 Pocket Model, made 1850–1873. Belgian-made Lefaucheux revolver, c. 1860 – 1865

Belgian-made Lefaucheux revolver, c. 1860 – 1865 A Russian Nagant M1895

A Russian Nagant M1895

North American Arms (NAA) mini revolver in .22 LR. It can fold into its own grip for safe belt clip carry.

North American Arms (NAA) mini revolver in .22 LR. It can fold into its own grip for safe belt clip carry.

References

- Richard A. Haynes (1 January 1999). THE SWAT CYCLOPEDIA: A Handy Desk Reference of Terms, Techniques, and Strategies Associated with the Police Special Weapons and Tactics Function. Charles C Thomas. p. 137. ISBN 9780398083434. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

Wheel Gun The slang term for a revolve handgun that references the rotation of the weapon's cylinder in its firing action, just as a wheel turns.

- Tara Dixon Engel (10 September 2015). The Handgun Guide for Women: Shoot Straight, Shoot Safe, and Carry with Confidence. Zenith Press. p. 58. ISBN 9781627888103. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

Let's start with a revolver, sometimes called a wheel gun.

- Morgan, Michael (2014). Handbook of Modern Percussion Revolvers. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4402-3898-7.

- Bakewell, Frederick (1859), Great Facts: A Popular History and Description of the Most Remarkable Inventions During the Present Century, Houlston and Wright, p. 264, ISBN 0608435368, archived from the original on 2023-04-22, retrieved 2022-09-09

- Howard L. Blackmore (1965). Guns and Rifles of the World. Chancellor Press. p. 80.

- Merrill Lindsay. "SIX SHOOTERS SINCE SIXTEEN HUNDRED" (PDF). Americansocietyofarmscollectors.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-09. Retrieved 2022-03-02.

- Kinard, Jeff (2004), Pistols: An Illustrated History of Their Impact, ABC-CLIO, pp. 61–62, ISBN 978-1-85109-470-7, archived from the original on 2023-04-22, retrieved 2020-05-12

- U.S. Patent X9430I1

- Tucker, Spencer C.; White, William E. (2011). The Civil War Naval Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-1-59884-338-5. Archived from the original on 2023-04-22. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- Fadala, Sam (1 December 2003). The Gun Digest Blackpowder Loading Manual. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications Craft. p. 28. ISBN 0-87349-574-8.

- Houze, Herbert G.; Cooper, Carolyn C.; Kornhauser, Elizabeth Mankin (2006). Samuel Colt: Arms, Art, and Invention. Yale University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-300-11133-9.

- U.S. Patent 12,648

- Flayderman, Norm (2001). Flayderman's Guide to Antique American Firearms ... and their values. Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 213. ISBN 0-87349-313-3.

- Jinks, Roy G.; Sandra C. Krein (2006). Smith & Wesson Images of America. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7385-4510-3.

- Sapp, Rick (2007). Standard Catalog of Colt Firearms. Iola, WI: Gun Digest Books. p. 79. ISBN 978-0896895348.

- Kinard, Jeff (2004). Pistols: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-85109-470-7.

- Cutshaw, Charles Q. (2011). Tactical Small Arms of the 21st Century: A Complete Guide to Small Arms From Around the World. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4402-2709-7.

- "Description des machines et procédés spécifiés dans les brevets d'invention, de perfectionnement et d'importation dont la durée est expirée, et dans ceux dont la déchéance a été prononcée, Volume 21, Issues 1793-1901". 1831.

- "Annales des arts et manufactures, ou Memoires technologiques sur les decouvertes modernes concernant les Arts, les Manufactures, l'Agriculture et le Commerce". 1818.

- Pauly, Roger A.; Pauly, Roger (2004). Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-313-32796-4.

- Group, Diagram (2007). The New Weapons of the World Encyclopedia: An International Encyclopedia from 5000 B.C. to the 21st Century. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-312-36832-6.

- Gibby, Darin (2011). Why America Has Stopped Inventing. New York: Morgan James Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-61448-048-8.

- Cumpston, Mike (2005). Percussion Pistols and Revolvers: History, Performance and Practical Use. iUniverse. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-595-35796-3.

- Tilstone, William J.; Savage, Kathleen A.; Clark, Leigh A. (1 January 2006). Forensic Science: An Encyclopedia of History, Methods, and Techniques. ABC-CLIO. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-1-57607-194-6. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- Eckstine, Roger (2013). Shooter's Bible Guide to Home Defense: A Comprehensive Handbook on How to Protect Your Property from Intrusion and Invasion. Skyhorse Publishing Company, Incorporated. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-62873-539-0.

- Supica, Jim; Nahas, Richard (2007). Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson. Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media, Inc. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-89689-293-4.

- Shideler, Dan (2010). Guns Illustrated 2011: The Latest Guns, Specs & Prices. Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media, Inc. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4402-1624-4.

- Ayoob, Massad (2007). The Gun Digest Book of Combat Handgunnery (Iola, Wisconsin ed.). Gun Digest Books. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-4402-1825-5.

- Campbell, Robert K. (2009). The Gun Digest Book of Personal Protection & Home Defense. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4402-2443-0.

- Keith, Elmer (1955). Sixguns. Salmon, Idaho: Wolfe Publishing Company. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-879356-09-2.

- Shideler, Dan (2011). Gun Digest Book of Guns & Prices 2011. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 583. ISBN 978-1-4402-1896-5.

- Shideler, Dan (26 June 2009). The Gun Digest Book of Modern Gun Values: The Shooter's Guide to Guns 1900-Present. Iola: Gun Digest Books. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-89689-824-0.

- Dockery, Kevin (2007). Future Weapons. Penguin Group (USA) Incorporated. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-425-21750-4.

- Taylor, Chuck (2009-08-29). "Why The Revolver Won't Go Away". Tactical-Life.com. Archived from the original on 2009-08-10. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- Ahern, Jerry (2010). Gun Digest Buyer's Guide to Concealed-Carry Handguns. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-1-4402-1743-2.

- Chicoine, David (2005). Guns of the New West: A Close Up Look at Modern Replica Firearms. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 236. ISBN 0-87349-768-6.

- Chun, Clayton (2013). US Army in the Plains Indian Wars 1865-1891. Osprey Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4728-0036-7.

- Ramage, Ken; Sigler, Derrek (2008). Guns Illustrated 2009. Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media, Inc. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-89689-673-4. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014.

- R.K. Campbell. "Tips For Lefties Shooting In a Right Handed World". GunWeek.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-16. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- Radielovic, Marko; Prasac, Max (2012). Big-Bore Revolvers. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4402-2856-8. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014.

- "English Patents of Inventions, Specifications: 1858, 2958 - 3007". 1859. Archived from the original on 2023-04-22. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- Taffin, John (2005). Kevin Michalowski (ed.). The Gun Digest Book of Cowboy Action Shooting: Guns Gear Tactics. Gun Digest Books. pp. 173–175. ISBN 0-89689-140-2.

- Ian V. Hogg (1978). The complete illustrated encyclopedia of the world's firearms. A & W Publishers. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-89479-031-7.

- Rick, Sindeband (2014-11-30). "Revolver Loading and Unloading". Archived from the original on 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2014-11-30.

- Sweeney, Patrick (2009). Gunsmithing - Pistols and Revolvers. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-1-4402-0389-3. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014.

- Wilson, Royce, "A Tale of Two Collectables", Australian Shooter magazine, March 2006.

- Sweeney, Patrick (2004). The Gun Digest Book of Smith & Wesson. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 284. ISBN 0-87349-792-9.

- S. P. Fjestad (1992). Blue Book of Gun Values, 13th Ed. Blue Book Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-9625943-4-2.

- 5 Different 3D Printed Gun Models Have Been Fired Since May, 2013 – Here They Are, 3D Print, September 10, 2014. (archive)

- Japanese Man Arrested For Printing His Own Revolvers, Tech Crunch, May 8, 2014. (archive)

- M.D., Vincent J.M. DiMaio (1998). Gunshot Wounds: Practical Aspects of Firearms, Ballistics, and Forensic Techniques, SECOND EDITION. CRC Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4200-4837-7.

- "Silenced 7.62 mm Nagant Revolver". Guns.connect.fi. 2000-09-18. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- "OTs-38 silent revolver". Modern Firearms. Archived from the original on 2009-08-26. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- Boorman, Dean K. (1 December 2002). The History of Smith & Wesson Firearms. Globe Pequot Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-58574-721-4.

- Kinard, Jeff (2004). Pistols: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-85109-470-7. Archived from the original on 2023-04-22. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- Shideler, Dan (2011). Gun Digest 2012. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-4402-2891-9. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014.

- Bishop, Chris (2006). The Encyclopedia of Weapons: From World War II to the Present Day. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay Press. p. 355.

- Troiani, Don; Kochan, James L.; Coates, Earl J.; James Kochan (1998). Don Troiani's Soldiers in America, 1754-1865. Stackpole Books. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8117-0519-6.

- Coggins, Jack (2012). Arms and Equipment of the Civil War. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-486-13127-6.

- Dizard, Jan E.; Muth, Robert M.; Andrews, Stephen P. (1999). Guns in America: A Reader. New York: NYU Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8147-1879-7.

- Shideler, Dan (10 May 2011). The Gun Digest Book of Guns & Prices 2011. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 555–556. ISBN 978-1-4402-1890-3.

- Muramatsu, Kevin (2013). The Gun Digest Book of Centerfire Rifles Assembly/Disassembly. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-4402-3544-3.

- Sapp, Rick (2007). Standard Catalog of Colt Firearms. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 198, 209. ISBN 978-1-4402-2697-7.

- Jones, Richard D.; White, Andrew (27 May 2008). Jane's Guns Recognition Guide 5e. HarperCollins. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-06-137408-1.

- Smith, Clint (September 2004). "Wheel guns are real guns". Findarticles.com. Guns Magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- Gromer, Cliff (August 2002). "New Guns of the Old West". Popular Mechanics: 86–89.

- Handloader Ammunition Reloading Journal, August 2009 edition in the "From the Hip" article by Brian Pearce. Page 32.

External links

- U.S. Patent RE124—Revolving gun

- U.S. Patent 1,304—Improvement in firearms

- U.S. Patent 7,613—Revolver

- U.S. Patent 7,629—Revolver

- U.S. Patent 12,648—Repeating firearm

- U.S. Patent 12,649—Revolver