Double-tuned amplifier

A double-tuned amplifier is a tuned amplifier with transformer coupling between the amplifier stages in which the inductances of both the primary and secondary windings are tuned separately with a capacitor across each. The scheme results in a wider bandwidth and steeper skirts than a single tuned circuit would achieve.

There is a critical value of transformer coupling coefficient at which the frequency response of the amplifier is maximally flat in the passband and the gain is maximum at the resonant frequency. Designs frequently use a coupling greater than this (over-coupling) in order to achieve an even wider bandwidth at the expense of a small loss of gain in the centre of the passband.

Cascading multiple stages of double-tuned amplifiers results in a reduction of the bandwidth of the overall amplifier. Two stages of double-tuned amplifier have 80% of the bandwidth of a single stage. An alternative to double tuning that avoids this loss of bandwidth is staggered tuning. Stagger-tuned amplifiers can be designed to a prescribed bandwidth that is greater than the bandwidth of any single stage. However, staggered tuning requires more stages and has lower gain than double tuning.

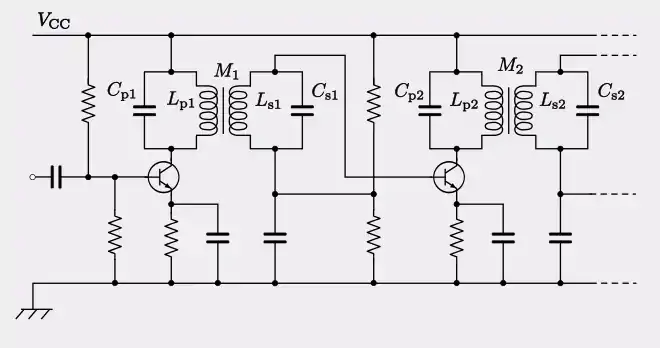

Typical circuit

The circuit shown consists of two stages of amplifier in common emitter topology. The bias resistors all serve their usual functions. The input of the first stage is coupled in the conventional way with a series capacitor to avoid affecting the bias. However, the collector load consists of a transformer which serves as the inter-stage coupling instead of capacitors. The windings of the transformer have inductance. Capacitors placed across the transformer windings form resonant circuits which provide the tuning of the amplifier.

A further detail that may be seen in this kind of amplifier is the presence of taps on the transformer windings. These are used for the input and output connections of the transformer rather than the top of the windings. This is done for impedance matching purposes; bipolar junction transistor amplifiers (the kind shown in the circuit) have a quite high output impedance and a quite low input impedance. This problem can be avoided by using MOSFETs which have a very high input impedance.[1]

The capacitors connected between the bottom of the transformer secondary windings and ground do not form part of the tuning. Rather, their purpose is to decouple the transistor bias resistors from the AC circuit.

Properties

Double tuning, as compared to single tuning, has the effect of widening the bandwidth of the amplifier and steepening the skirt of the response.[2] Tuning both sides of the transformer forms a pair of coupled resonators which is the source of the increased bandwidth. The gain of the amplifier is a function of the coupling coefficient, k, which is related to the mutual inductance, M, and the primary and secondary winding inductances, Lp and Ls respectively, by

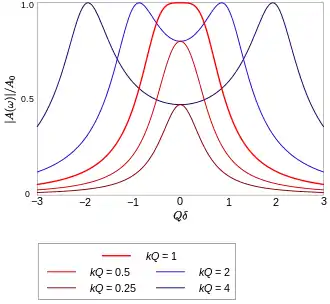

There is a critical value of coupling at which the gain of the amplifier is a maximum at resonance. Below this critical value, there is a single peak in the frequency response with the amplitude peaking at resonance and the peak decreasing as k decreases. Such a response is said to be undercoupled, At values of k above critical coupling the response starts to split into two peaks. These peaks become narrower and further apart as k increases and the gap between them (centred on the resonant frequency) becomes progressively deeper. Such a response is said to be overcoupled.[3]

A critically coupled amplifier has a response that is maximally flat. This response can also be achieved without transformers with two stages of a stagger-tuned amplifier. Unlike staggered tuning, double tuning usually tunes both resonators to the same resonant frequency.[4] However, a designer might choose to design an overcoupled amplifier in order to achieve a wider bandwidth at the expense of a small dip (typically 3 dB to maximize the 3 dB bandwidth) in the centre of the frequency response.[5]

Like synchronous tuning, adding more stages of double-tuned amplifiers has the effect of reducing the bandwidth. The 3 dB bandwidth of n identical stages, as a fraction of the bandwidth of a single stage, is given approximately by,

This expression applies only to small fractional bandwidths.[6]

Analysis

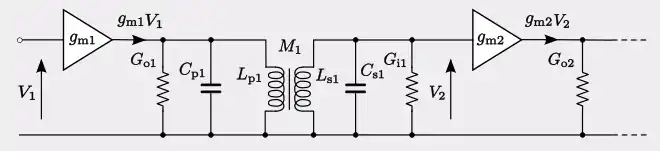

The circuit can be represented in a more generic way by replacing the amplifiers with a generalised transconductance amplifier as shown.

- where (omitting the stage number suffixes),

- gm is the transconductance of the amplifiers

- Go is the output conductance of the amplifiers

- Gi is the input conductance of the amplifiers.

Typically, a design will make the resonant frequencies and Qs on the primary and secondary sides identical, such that,

- and,

- where ω0 is the resonant frequency expressed in units of angular frequency and the subscripts p and s refer respectively to components on the primary and secondary side of the transformer.

Stage gain

With the above assumptions, the voltage gain, A of one stage of the amplifier can be expressed as

- where

- is the imaginary unit

- is the maximum gain the stage can possibly deliver, and

- is the frequency expressed as the fractional frequency deviation from the resonant frequency.

Peak frequency

With less than critical coupling, there is one peak in the response occurring at resonance. Above critical coupling, there are two peaks at frequencies given by

- where δL and δH are respectively the low and high frequencies of the peaks expressed as fractional deviation.

With critical coupling or above, the peaks reach the maximum gain available from the amplifier.

References

- Bhargava et al., pp. 382–383

- Gulati, p. 432

-

- Bakshi & Godse, p. 5.25

- Chattopadhyay, p. 195-196

- Chattopadhyay, p. 196

- Bakshi & Godse, p. 5.26

- Bakshi & Godse, p. 5.29

- Bakshi & Godse, pp. 5.20–5.26 (for entire analysis section)

Bibliography

- Bakshi, Uday A.; Godse, Atul P., Electronic Circuit Analysis, Technical Publications, 2009 ISBN 8184310471.

- Bhargava, N. N.; Gupta, S. C.; Kulshreshtha D. C., Basic Electronics and Linear Circuits, Tata McGraw-Hill, 1984 ISBN 0074519654.

- Chattopadhyay, D., Electronics: Fundamentals and Applications, New Age International, 2006 ISBN 8122417809.

- Gulati, R. R., Monochrome and Colour Television, New Age International, 2007 ISBN 8122416071.