Samuel Prescott

Samuel Prescott (August 19, 1751 – c. 1777) was an American physician and a Massachusetts Patriot during the American Revolutionary War. He is best known for his role in Paul Revere's "midnight ride" to warn the townspeople of Concord, Massachusetts, of the impending British army move to capture guns and gunpowder kept there at the beginning of the American Revolution. He was the only participant in the ride to reach Concord.

Samuel Prescott | |

|---|---|

Monument at the Paul Revere Capture Site. From here, Samuel Prescott carried on Revere's mission. | |

| Born | August 19, 1751 |

| Died | c. 1777 (aged 25–26) possibly Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Abel Prescott Jr. (brother) |

Early life

Little is known for certain about Prescott's life outside of his involvement in the dramatic events before and during the Battles of Lexington and Concord. He was born on August 19, 1751. He grew up in Concord, Massachusetts, where his family had lived for generations. He became a physician, as his father and grandfather had been before him.[1]

According to tradition, Samuel Prescott was courting Lydia Mulliken of Lexington, Massachusetts, just prior to the outbreak of the American Revolution.[2] Lydia lived with her widowed mother, four brothers and two sisters in a home across Cambridge Road from Munroe's Tavern. Her older sibling, Nathanial, worked in his late father's clock shop and was a member of Captain John Parker's militia.

Due to the fact that Paul Revere referred to Prescott as a "high son of Liberty," (meaning an ardent supporter of the Patriot cause), some have speculated that Prescott had ties to the Sons of Liberty or acted as a courier for the Committees of Correspondence prior to the start of the Revolution.[3]

The Midnight Ride

_(14578828258).jpg.webp)

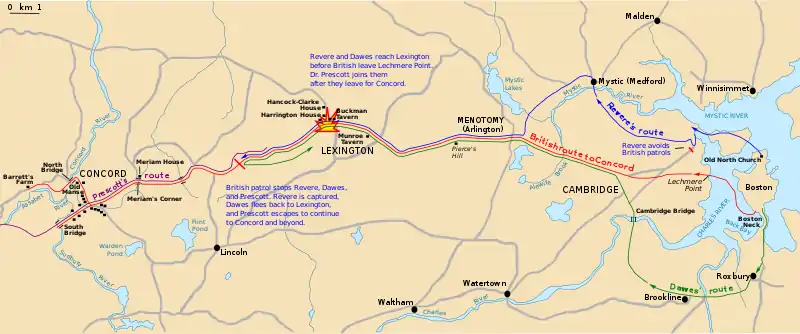

On the evening of April 18, 1775, Paul Revere and William Dawes were dispatched by Joseph Warren to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were then in Lexington, that a British expedition was on its way to arrest them. Warren also instructed Revere and Dawes to warn provincial officials in Concord that British troops intended to confiscate or destroy the armaments being amassed there by the province's militia. [4] Revere and Dawes took different routes but met in Lexington about midnight and successfully warned Adams and Hancock, who quickly left Lexington. Revere and Dawes then proceeded towards Concord to complete their second mission.[5]

Samuel Prescott was headed home to Concord from Lexington when he encountered Revere and Dawes on horseback around 1 a.m. on April 19. Revere later described their meeting in his 1775 deposition to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and in a 1798 letter to Jeremy Belknap.[6] Revere claimed that Prescott was a "high son of Liberty"--suggesting that he was trustworthy. Upon hearing about their mission, Prescott offered to assist Revere and Dawes, pointing out that he was known in the area and residents would be more likely to believe a warning coming from him rather than strangers.[1]

Proceeding along the road to Concord, the three riders warned residents of several houses in Lincoln, Massachusetts, by knocking on doors. It was in Lincoln, not far from the Concord town line, that a British mounted patrol intercepted the three riders. The British soldiers were part of a larger scouting party sent out from Boston the previous evening to stop any provincial alarm riders or couriers.[7] The soldiers captured Revere but both Prescott and Dawes escaped. Dawes was thrown from his horse and went back to Lexington. Prescott, according to Revere's account, took off on horseback towards a stone wall, jumped his horse over it, and disappeared into dense woods.[8] After riding through woods and swamp, Prescott emerged at the Hartwell Tavern. He alerted the Hartwell family who, in turn, raced off to warn others.[9] Word soon reached Capt. William Smith, commander of the Lincoln minutemen, who ordered the town bell rung as a signal for his company to muster.[10]

On his way to Concord, Prescott alerted other houses in Lincoln and soon additional riders rode off to alert other towns.[11] When Prescott arrived in Concord, he gave word to the sentry there and the Concord First Parish Church bell was rung to alert the town. Thus Prescott completed the second objective given to Revere and Dawes. In Concord, Prescott bid his brother Abel to ride to Sudbury to alert companies there while, according to tradition, Samuel rode to Acton and Stow to carry the alarm there.[12] His brother Abel, that same day was fired on by British soldiers as he was returning from the neighboring town, whither he had been to apprise the people of the approach of the "regulars" (so called), and slightly wounded in the side, but succeeded in making his escape by secreting himself in the house of a Mrs. Heywood. Due to Prescott's efforts that night, the minuteman and militia companies in numerous towns were alerted, mustered, and marched to Concord in time to engage the British Army at the Old North Bridge and other locations along the road to Boston.

Later career

Details relating to Prescott's life after the ride are scant and inconclusive. According to historian D. Michael Ryan, a record of a "Dr. Sall Prescott" serving as a surgeon at Fort Ticonderoga in 1776 has led many historians to conclude that Prescott served the Continental Army in a medical capacity. A Revolutionary War veteran from Ashburnham, Massachusetts, recorded in his memoir that he had been imprisoned by the British in a prison in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with a Dr. Prescott. According to this account, Prescott died in prison in 1777. Although corroborating evidence that this was Dr. Samuel Prescott of Concord is lacking, these details are most often accepted as fact.[13]

Legacy

Prescott's arrival in Concord is reenacted every year at midnight on April 19. The reenactment is preceded by a Patriots' Ball and a procession by modern day Minuteman ceremonial honor guards and fife and drum units. Prescott's supposed ride through Acton is reenacted every Patriots' Day beginning in East Acton and concluding at the Liberty Tree Farm, where once stood the home of a minuteman named Simon Hunt.

In 1965, the Concord Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution placed a memorial plaque to Prescott at the location of his home in Concord.

References

- Tourtellot (2000), p. 100.

- Langguth (1988), p. 235.

- Ryan (2007), p. 35.

- Langguth (1988), p. 97.

- Fischer (1994), pp. 110–111.

- Fischer (1994), p. 329.

- Fischer (1994), p. 89.

- Fischer (1994), p. 143.

- The Prescott Memorial, Or, A Genealogical Memoir of the Prescott Families in America In Two Parts, William Prescott (1870), p. 66

- Hafner, pp. 10–11.

- Fischer (1994), p. 144.

- Ryan (2007), p. 39.

- Ryan (2007), pp. 39–40.

Sources

- Fischer, David Hackett (1994). Paul Revere's Ride. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195088476.

- Hafner, Donald L. "Mary Hartwell and the Alarm of April 19, 1775" (PDF). Minute Man National Historic Park.

- Langguth, A.J. (1988). Patriots: The Men Who Started the American Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671523756.

- Marvin, Abijah P. (1879). History of the Town of Lancaster, Massachusetts: from first settlement to the present time 1643–1879. The Town of Lancaster, Massachusetts.

- Ryan, D. Michael (2007). Concord and the Dawn of Revolution. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 9781596291867.

- Selesky, H. E. (2006). History of the Town of Lancaster, Massachusetts: from first settlement to the present time 1643–1879. The Town of Lancaster, Massachusetts.

- Tourtellot, Arthur (2000) [1959]. Lexington and Concord, The Beginning of the War of the American Revolution. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393320565.

- The Prescott memorial, or, A genealogical memoir of the Prescott families in America by Prescott, William, 1788-1875. Published 1870. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.