Dracunculus (nematode)

Dracunculus is a genus of spiruroid nematode parasites in the family Dracunculidae.

| Dracunculus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dracunculus medinensis larvae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Secernentea |

| Order: | Camallanida |

| Family: | Dracunculidae |

| Genus: | Dracunculus Reichard, 1759 |

| Species | |

|

Dracunculus alii | |

The worms can reach a metre in length. If one simply pulls off the protruding head of the worm, the worm will break and leak high levels of foreign antigen which can lead to anaphylactic shock and fast death of the host. Hence it is important to remove the worm slowly (over a period of weeks). This is typically undertaken by winding the worm onto a stick (say, a matchstick), by a few centimetres each day.

Life cycle

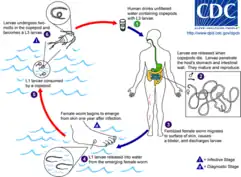

All members of Dracunculus are obligate parasites of mammals or reptiles. Adult females reside just under the skin, and eventually form a blister in the host's skin through which they access the environment. When the blister comes into contact with water, the female releases several hundred thousand first-stage ("L1") larvae. L1 larvae must be ingested by a cyclopoid copepod, which serves as an intermediate host. Inside the copepod, the larvae develop to the third-stage ("L3"). Definitive hosts acquire Dracunculus by incidentally ingesting infected copepods while drinking water, or by consuming a paratenic host (e.g. a frog or fish) that has itself consumed a copepod. Inside the definitive host, the L3 larvae leave the digestive tract and migrate to deeper tissues, where within 60–70 days they undergo their final two molts to form sexually mature adults. Male and female adult worms then mate, and pregnant females migrate back to the host's skin – typically to an extremity – and form a blister to repeat the cycle.[1] Following the release of her larvae, the female worm dies, and is either extracted by the affected animal, or falls back into the tissue and is calcified.[1]

Description

Once released, the L1 larvae measure 0.3–0.9 millimeters in length and feature a very long tapered tail. As they develop into L3 larvae, they lose the tapered tail, broaden, and develop a tri-lobed tail; the lengths of most L3 larvae are unknown.[1] Adults of both sexes are narrow yellow-white colored worms, with a rounded front-end, and a conical tail-end with a pointed tip. Females of different species within the genus tend to look similar, and can rarely be distinguished on morphology alone.[1] The body of a fertilized adult female is almost completely filled by its uterus, distended with L1 larvae.[1] Adult female Dracunculus worms are noted for their extraordinary length, with some growing up to 100 centimeters long. Males are much smaller (16 – 40 millimeters) and are relatively rare – in some species the male has never been described.[1]

Distribution

Dracunculus worms are distributed globally, though each species has a narrower range. The majority of Dracunculus species described infect reptiles – predominantly snakes.[1] These are spread across the globe, with D. ophidensis in the United States, D. brasiliensis in Brazil, D. coluberensis and D. alii in India, D. houdemeri in Vietnam, D. doi in Madagascar, D. dahomensis in Benin, D. oesophageus in Italy, and D. mulbus in Australia and Papua New Guinea. The only species known to infect a non-snake reptile is D. globocephalus which has been described in snapping turtles in the United States and Costa Rica.[1]

Most mammal-infecting species are in the Americas, with D. insignis infecting several wild and domestic mammals in the United States and Canada, D. lutrae infecting river otters in the United States and Canada, and D. fuelleborni infecting big-eared opposums in Brazil.[1] The major exception is D. medinensis, by far the most studied Dracunculus as it infects humans. D. medinensis was historically widespread in Africa and South Asia,[1] but is now limited to dozens of cases annually in humans and domestic dogs, and may soon be driven to extinction.[2]

Species

Reptile-infecting species

There are 14 accepted Dracunculus species, 10 of which infect reptiles. Eurasia hosts several reptile-infecting Dracunculus species. D. oesophageus was originally described from the esophagus of a viperine snake Natrix maura, and has been described several times since. The remaining three Eurasian reptile-infecting species have been described a single time each: D. coluberensis from an Indian trinket snake, and D. alii and D. houdemeri from Checkered keelback snakes in India and Vietnam respectively.[1]

The only snake-infecting Dracunculus species known in North America is D. ophidensis. It was originally described in garter snakes in Michigan and Minnesota by Sterling Brackett in 1938, and has since been reported in blackbelly garter snakes from Mexico, as well as northern water snakes and a plain-bellied water snake in Michigan.[1] D. brasiliensis is the only described snake-infecting Dracunculus in South America. It was described in 2009 based on a single female worm from an anaconda in Brazil, and has since also been found in a Brazilian brown-banded water snake.[1] Several worms that appear to be from the genus Dracunculus have been described in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean; however, they have not been described in sufficient detail to assign them to a species.[1] The Americas are also home to the only known turtle-infecting Dracunculus (also the only species that infects a non-snake reptile), D. globocephalus. First described in 1927 in Oklahoma and Illinois, it is now found in snapping turtles across the United States, as well as the South American snapping turtle in Costa Rica.

Africa hosts two known snake-infecting species. Both male and female D. doi were described from Madagascar ground boas in 1960 and 1973 respectively. D. dahomensis has been described only from a captive African rock python.[1]

In Australia, the only known snake-infecting Dracunculus is D. mulbus, described from numerous water pythons in Northern Australia in 2007. It has since been described in Papua New Guinea's Papuan olive python as well.[1]

Mammal-infecting species

Just four Dracunculus species are known to infect mammals, of which the best known is the human parasite D. medinensis. Historically spread across Africa and South Asia, a major eradication effort has restricted D. medinensis to just Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan.[1] Case numbers have similarly fallen, from an estimated 3.5 million per year at the 1986 start of the eradication program, to just 15 in 2021.[3][4] D. medinensis is now most common in dogs, particularly in Chad, where it may spread via fish or frogs as paratenic hosts.[5]

D. insignis infects dogs and wild carnivores, causing cutaneous lesions, ulcers, and sometimes heart and vertebral column lesions. Like D. medinensis, it is also known as Guinea worm, as well as Dragon or Fiery Dragon. The range of D. insignis is limited to North America.

D. fuelliborni parasitizes opossum, D. lutrae parasitizes otters, and D. ophidensis parasitizes reptiles.

References

- Cleveland CA, Garrett KB, Cozad RA, Williams BM, Murray MH, Yabsley MJ (December 2018). "The wild world of Guinea Worms: A review of the genus Dracunculus in wildlife". Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 7 (3): 289–300. doi:10.1016/j.ijppaw.2018.07.002. PMC 6072916. PMID 30094178.

- "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". World Health Organization. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "25. Dracunculus medinensis". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. pp. 285–290. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Dracunculiasis Eradication: Global Surveillance Summary, 2021 (Report). World Health Organization. 27 May 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- Molyneux D, Sankara DP (April 2017). "Guinea worm eradication: Progress and challenges- should we beware of the dog?". PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 11 (4): e0005495. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005495. PMC 5398503. PMID 28426663.

External links

- "Dracunculus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 6 February 2017.