Frock coat

A frock coat is a formal men's coat characterised by a knee-length skirt cut all around the base just above the knee, popular during the Victorian and Edwardian periods (1830s–1910s). It is a fitted, long-sleeved coat with a centre vent at the back and some features unusual in post-Victorian dress. These include the reverse collar and lapels, where the outer edge of the lapel is often cut from a separate piece of cloth from the main body and also a high degree of waist suppression around the waistcoat, where the coat's diameter round the waist is less than round the chest. This is achieved by a high horizontal waist seam with side bodies, which are extra panels of fabric above the waist used to pull in the naturally cylindrical drape. As was usual with all coats in the 19th century, shoulder padding was rare or minimal.

In the Age of Revolution around the end of the 18th century, men abandoned the justaucorps with tricorne hats for the directoire style: dress coat with breeches or increasingly pantaloons, and top hats. However, by the 1820s, the frock coat was introduced along with full-length trousers, perhaps inspired by the then casual country leisure wear frock. Early frock coats inherited the higher collars and voluminous lapels of the dress coat style at the time, and were sometimes offered in different, albeit increasingly dark, colours. Within its first next few years, though, plain black soon became the only established practice, and with a moderate collar. The top hat followed suit.

Although black trousers did occur, especially at daytime, the black frock coat was commonly worn with charcoal grey, pin-striped or checked formal trousers. The single-breasted frock coat sporting the notched (step) lapel was more associated with day-to-day professional informal wear. Yet, from the end of the 19th century, with the gradual introduction of the lounge suit, the frock coat came to embody the most formal wear for daytime. Especially so when double-breasted with peaked lapels, a style sometimes called a Prince Albert after Prince Albert, consort to Queen Victoria. The formal frock coat only buttoned down to the waist seam, which was decorated at the back with a pair of buttons. The cassock, a coat that is buttoned up to the neck, forming a high, stand-up Roman collar for clergymen, was harmonised to the style of the contemporary frock coat.

By the late 19th century, the knee-length dress coat, morning coat and shorter cut lounge suit were all standardized. While the dress coat and the morning coat are knee-length coats like the frock coat and traditionally share the waist seam of the precursor, they are distinguished by the cutaway of the skirt which gives dress coats and morning coats tails at the back. From the 1920s, the frock coat was increasingly replaced as day formal wear by the cut-away morning coat. In 1936, it was suspended from the protocol of audiences at the British royal court. While effectively relegated to a rarity in formal wear ever since, it does occur in certain formal marriages and traditional processions.

Name

The name frock coat appeared out from the earlier frock.

Earlier terminology also used redingote (or redingotte, redingot),[1] derived from a French alteration of the English "riding coat", an example of reborrowing.

History

Frock coats emerged during the Napoleonic Wars, where they were worn by officers in the Austrian and various German armies during campaign. They efficiently kept the wearer warm as well as protecting his uniform. Privates and non-commissioned officers would wear greatcoats on campaign.

The earlier frock

During the mid seventeenth century the older doublets, ruffs, paned hose and jerkins were replaced by the precursor to the three piece suit comprising waistcoat, tight breeches and a long coat called a justacorps, topped by a powdered wig and tricorne hat. This coat, popularised by Louis XIII of France and Charles II of England, was knee length and looser fitting than the later frock coat, with turn-back cuffs and two rows of buttons. English and French noblemen often wore expensive brocade coats decorated with velvet, gold braid, embroidery and gold buttons to demonstrate their wealth.[2]

Before the frock coat existed, there was another garment called the frock in the 18th century, which was probably unrelated to the frock coat, sharing only a similarity in name. The earlier frock was originally country clothing that increasingly became common around 1730. Formal dress was then so elaborate that it was impractical for everyday wear, so the frock became fashionable as half dress, a less formal alternative. By the 1780s the frock was worn widely as town wear and, towards the end of the 18th century, started to be made with a single-breasted cut away front and tails. It was thus the precursor to the modern dress coat worn with white tie dress code.

These relations can be seen in similar foreign terms. The modern word for a dress coat in Italian, French, Romanian and Spanish is frac; in German and Scandinavian languages Frack; and Portuguese fraque, used in the late 18th century to describe a garment very similar to the frock, being a single or double-breasted garment with a diagonally cutaway front in the manner of a modern morning coat. Even coats with horizontally cut away skirts like a dress coat were referred to as a frock in the late eighteenth and very early 19th century, before being renamed to dress coat.

This suggests that the earlier frock from the 18th century is more the direct ancestor of the modern dress coat, whereas the frock coat in the 19th century, the subject under discussion here, is a different garment altogether with separate military origins in the 19th century. However a remote historical connection to the frock cannot entirely be excluded, as is the case with similar looks variably referred to as redingote or riding coat.

Other meanings of the term frock include clerical garb and a type of woman's dress combining a skirt with a shirt–blouse top.

Military uniforms

The first military frock coats were issued late in the Napoleonic Wars to French line infantry and Prussian Landwehr troops.[3] Unwilling to soil the expensive tail coats on campaign, the French adopted a loose fitting single-breasted coat with contrasting collar and cuffs. The Germans, having been devastated by years of war, were unable to afford elaborate uniforms like the British line infantry and chose a peaked cap and double-breasted blue coat,[4] again with contrasting collar and cuffs, as these were cheaper to produce for the large numbers of recruits, smart enough for full dress and more practical for campaigns.

By the 1840s, frock coats were regulation for the American, Prussian, Russian[5] and French armies. By 1834 officers of the British Army had adopted a dark blue/black frock coat for ordinary duties, derived from an earlier greatcoat worn during the Napoleonic period.[6] US army officers were first issued navy blue frocks during the Mexican War, with gold epaulettes and peaked caps of the German pattern. Enlisted USMC personnel received a double breasted version with red piping worn with a leather stock and shako to reflect their status as an elite unit. Infantry soldiers continued to be issued the 1833 pattern shell jacket until the M1858 uniform complete with French style kepi entered service shortly before the US Civil War.[7]

The earlier redingote

The men's redingote was an eighteenth-century or early-nineteenth-century long coat or greatcoat, derived from the country garment (i.e. derived from "riding coat") with a wide, flat collar called a frock. In French and several other languages, redingote is the usual term for a fitted frock coat. The form a men's redingote took could be of the tightly fitting frock coat style or the more voluminous, loose "great coat" style, replete with overlapping capes or collars, such as a "garrick" redingote, depending on fashion throughout its popularity.

The origins and rise of the frock coat

When the frock coat was first worn, correct daytime full dress was a dress coat. The frock coat began as a form of undress, the clothing worn instead of the dress coat in more informal situations. The coat itself was possibly of military origin. Towards the end of the 1820s, it started to be cut with a waist seam to make it more fitted, with an often marked waist suppression and exaggerated flair of the skirt. This hour-glass figure persisted into the 1840s. As the frock coat became more widely established around the 1850s, it started to become accepted as formal day time full dress, thus relegating the dress coat exclusively to evening full dress, where it remains today as a component of white tie. At this period, the frock coat became the most standard form of coat for formal day time dress. Through most of the Victorian era it continued to be worn in similar situations those in which the lounge suit is worn today such as in weddings, funerals and by professionals. It was the standard business attire of the Victorian era.

Prince Albert, consort to Queen Victoria, is usually credited with popularising the frock coat and even gave a synonym for its double-breasted version, a "Prince Albert". During the Victorian era, the frock coat rapidly became worn universally in Britain, Europe and America as standard formal business dress or for formal daytime events. It was considered the most correct form of morning dress for the time.

Notably, however, this time was before contemporary established dress code terminology and so definitions of formal attire, as well as morning and evening attire, were not altogether according to later standards.

The decline of the frock coat

Around the 1880s and increasingly through into the Edwardian era, an adaptation of the riding coat called a Newmarket coat, that rapidly and ever since became known as a morning coat, began to supplant the frock coat as daytime full dress. Once considered a casual equestrian sports coat, the morning coat slowly started to become both acceptable and increasingly popular, as a standard day-time town full dress alternative to the frock coat, a position which the morning coat enjoys to this day.

The morning coat was particularly popular amongst fashionable younger men and the frock coat increasingly came to be worn mostly by older conservative gentlemen. The morning coat gradually relegated the frock coat only to more formal situations, to the point that the frock coat eventually came to be worn only as court and diplomatic dress.

The lounge suit was once only worn as smart leisure wear in the country or at the seaside but in the middle of the 19th century started to rise rapidly in popularity. It took on the role of a more casual alternative to the morning coat for town wear, moving the latter up in the scale of formality. The more the morning coat became fashionable as correct daytime full dress, the more the lounge suit became acceptable as an informal alternative. Finally the frock coat became relegated to the status of ultra-formal day wear, worn only by older men. At the most formal events during the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, heads of government wore the frock coat but at more informal meetings they wore morning coats or even a lounge suit. In 1926, George V hastened the demise of the frock coat when he shocked the public by appearing at the opening of the Chelsea Flower Show wearing a morning coat. The frock coat barely survived the 1930s only as an ultra-formal form of court dress, until being finally officially abolished in 1936 as official court dress by Edward VIII (who later abdicated to become the Duke of Windsor). It was replaced by the morning coat, thus consigning the frock coat protocol-wise to the status of historic dress at the British royal court.

Since that time it has been worn sparingly, albeit arguably not altogether vanished (see section on contemporary use further below).

Composition

Formal wear

| Part of a series on |

| Western dress codes and corresponding attires |

|---|

|

Legend:

|

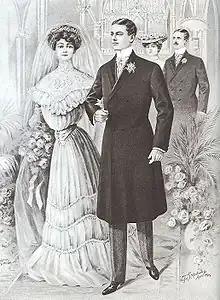

Frock coats worn with waistcoat and formal striped trousers are still very occasionally worn as daytime formal wear, especially to weddings, as an alternative to morning coats, in order to give the wedding attire a Victorian flavour. They are today usually only worn by the wedding party, where elements of historical costume are more acceptable and even this practice is unusual, as its role as a formal ceremonial coat in daytime formal wear has been long supplanted in modern dress code by the morning coat. Like morning coats, frock coats are only worn for daytime formal events before 5pm. and no later than until around 7pm.

Prior to the establishment of morning dress around the turn of the century in 1900, the expression "morning dress" tended to refer to frock coat, while gradually extending to mean both the frock coat and morning dress in the contemporary sense.[8]

The morning dress for gentlemen is a black frock coat or a black cut-away, white or black vest, according to the season, gray or colored pants, plaid or stripes according to the fashion, a high silk stove pipe hat and a black scarf or necktie. A black frock coat with black pants is not considered a good combination.. The morning dress is suitable for garden parties, Sundays, social teas, informal calls, morning calls and receptions.

— Our Deportment(1879)

At afternoon funerals, wear a frock coat and top hat. Should the funeral be your own, the hat may be dispensed with.

— The Cynic's Rules of Conduct (1905)

Cloth

_-_DPLA_-_cc9ea38679ca3513a69e97a2623a8ccc_(page_1)_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Standard fibres used for the frock coat included wool and vicuña. The most common weaves were known as broadcloth and duffel, both so called "heavy wools" manufactured along a process originating from Flanders in the 11th century (Flemish cloth). The standard colour of a civilian frock coat was solid black but later, in the Victorian era, charcoal grey became an acceptable but less common alternative and Midnight Blue was an even rarer alternative colour. For business and festive occasions the revers was lined with black silk facings (either satin or grosgrain). For funerals black frock coats without self-faced revers were worn with a matching black waistcoat. In military uniforms a wider variety of colours was and is common, prompting such colour names as "navy blue" and "cadet grey".

On more formal outings the coat was worn with a pair of cashmere striped morning trousers (cashmere stripes refers to the muted design in black, silver and charcoal grey, not the fibres of the cloth). However, trousers of muted checks were also worn in slightly more informal situations. In keeping with the rules set for morning dress, trousers matching the coat were considered a somewhat less formal alternative.

A matching black waistcoat was worn for more formal business or more solemn ceremonies. During the earlier Victorian period, colourful fancy waistcoats of silk were noted as being worn by gentlemen such as Charles Dickens. In summer a white or buff coloured linen waistcoat could be worn. For festive occasions a lighter coloured waistcoat such as light grey was permissible.

Cut

The length of the skirt of the frock coat varied during the Victorian era and Edwardian era according to fashion. The most conservative length became established as being to the knees but fashion conscious men would follow the latest trends to wear them either longer or shorter. Similarly, the height of the waist – the point of maximal waist suppression – changed according to fashion. During its heyday, the frock coat was cut following the 19th century ideal of flattering the natural elegance of the naked figure, based on the ideals of Neoclassicism that admired the depiction of the idealised nude in Classical Greco-Roman sculpture. The elegance of the form of the frock coat derived from its hourglass shape with a closely cut waist which at times around the 1830s-40's was reinforced further with padding to round out the chest. A cut with an ideal hourglass silhouette was achievable because coats during this era were all made bespoke, individually cut to the exact measurements of the customer. The 19th century aesthetics of tailoring contrasted markedly to the modern style of cutting suits which involves a greater degree of drape (fullness), as established by the great early 20th century Savile Row tailor Frederick Scholte. Caution needs to be exercised by modern tailors trained to create the drape cut style of modern lounge suits to minimise drape – particularly around the waist – when cutting a historically accurate frock coat. Sometimes, modern lounge suit coats with an unusually long skirt are referred to by ready-to-wear makers as a 'frock coat' but these lack the waist seam, resulting in the fuller drape more typical of a modern overcoat or a lounge suit jacket. The silhouette of the historically accurate frock coat has the waist seam precisely tailored to permit the classical and elongating hourglass figure with the strong waist suppression.

Details

Another characteristic of frock coats was their lack of any outer pockets. Only late in the Victorian and Edwardian era were they ever made with a chest pocket to sport a pocket square, a feature more typical of the modern lounge suit. Oscar Wilde, a famous dandy of his time, was often seen in portraits wearing just such a model but this was rather rare on frock coats; while in keeping with the flamboyant nature of Wilde's dress, it was frowned upon by traditionalists. Side pockets were always absent from frock coats but pockets were provided on the inside of the chest or inside the top part of the tail.

The buttons on a frock coat were always covered in cloth, often to match the silk on the revers, showing in the triangle of lining wrapped over the inside of the lapels. Another common feature was the use of fancy buttons with a snow-flake or check pattern woven over it.

Through most of the Victorian era until towards the end, the lapels were cut separately and sewn on later, apparently because it made the lapel roll more elegantly from bottom up. The lapel revers from the inside of the coat wrapped over to the front, creating a small triangle of silk, while the outer half was cut from two strips of the body fabric. This was a feature of double-breasted frock coats used on all such coats but morning and dress coats, which had previously followed this practice, began to be made with attached lapels (wholecut) around the end of the Edwardian era. Through the Victorian era, a row of decorative button holes was created down the lapel edge but by Edwardian period these were reduced down to just the one lapel boutonnière button hole.

Turn back cuffs on the sleeves, similar to the turn ups (cuffs in American English) on modern trouser hems, were standard, with two buttons on the cuff.

Another rare feature was the use of decorative braiding around the sleeve cuffs and lapel edges.

Accessories

Proper accessories to wear with the frock coat included a non-collapsible top hat and a boutonnière in the lapel. A Homburg hat was considered too informal to wear with proper formal morning dress. During the Victorian and Edwardian era, button boots with a single row of punching across the cap toe were worn along with a cane. On cold days, it was common to wear a frock overcoat, a type of overcoat cut exactly the same as the frock coat, with the waist seam construction only a little longer and fuller to permit it to be worn over the top of the frock coat. Patent leather dress boots were worn up until the Edwardian era with morning dress. The practice of wearing patent leather shoes is today reserved strictly for evening formalwear. Trousers are uncuffed and worn with braces to avoid the top of the trousers from showing underneath the waistcoat. Only white shirts were worn with frock coats. The shirt was worn with a standing detachable collar with either wingtips or "imperial" style (plain standing). The most standard neckwear was a formal cravat . The cravat was tied in the Ascot knot characterised by way the ends cross over in front or alternatively in a Ruche knot, tied like a four-in-hand knot of a modern necktie. A decorative cravat pin often adorned with a precious stone or pearl was used to keep the cravat tidy. The cravat was usual with a frock coat when worn in more formal occasions through the Victorian and Edwardian eras, although the long necktie came to be worn increasingly after the turn of the century in the same manner as it is today with morning dress. The practice of wearing bow ties as an acceptable alternative with formalwear fell away after the late Victorian to early Edwardian era and became relegated to eveningwear, as remains the case in the 21st century. As with a formal shirt for white tie, cuffs were single (rather than double) cuffed and made to close with cufflinks. The waistcoat was usually double-breasted with peaked lapels. Formal gloves in light grey suede, chamois or kid leather were also required.

Informal frock coat suits

The solid black garment described above was widely used but before the lounge suit became popular, there was a need for a more informal garment for smart casual wear. A version of the frock coat was used here too, with matching trousers and a more informal cloth, featuring stripes or the check shown in the plate opposite. The waistcoat, instead of being black as usual in the formal version, was matching or odd. Until the modern cut away morning coat was worn, the single breasted frock coat was called a morning coat and was used in such a less formal context and double breasted coats made this way would often not fasten, being held loosely together in much the same way the modern morning coat is, with a single link.[9]

The accessories for the two styles depended on the intended use of the coat: for more formal settings, the outfit might still have striped trousers and demand a top hat and white gloves; for business, by the turn of the century, the morning coat was used (again, this referred to a single breasted frock coat then, not the modern morning coat). This last was accompanied by a business collar (such as winged collar, not a standing Imperial collar); a four in hand tie (as opposed to the formal cravat and puff) and a soft Derby or Homburg.[9]

Modern use

General

Although ceasing to be required by protocol as formal attire at the British royal court in 1936, at the order of the short-reigning King Edward VIII, the frock coat has not altogether vanished as modern civilian formal wear.

The state funeral of Winston Churchill in 1965 included wearers of frock coats.[10]

Savile Row tailor and reinnovator Tommy Nutter (1943– 1992) was a frequent wearer.

Frock coats, albeit often in other colours than black, survive until this day in the livery of hotel staff.

King Tupou VI of Tonga (born 1959) is a frequent wearer of frock coats.

Examples of frock coats in fashion in the 21st century include Alexander McQueen in 2012,[11] Prada's autumn edition in 2012, and Paul Smith in 2018.[12]

Frock coats still appear in certain traditional Catholic processions, such as the Blutritt in Germany.

Some wedding grooms apply more or less creative civil or military variants of frock coats. In the civilian wear cases it is sometimes accompanied by the same creativity in terms of ascot ties. As a prominent example, when Prince Harry married Meghan Markle in 2018, he and his brother and best man Prince William opted for military full dress uniform variants of frock coats.

Military uniforms

The cut of a frock coat with a waist seam flatters a man's figure, as opposed to a sack coat, and such frock coats remained part of some 21st-century military uniforms. They can either be single-breasted, as in some army uniforms, or double-breasted as in both army and navy uniforms. An example of the latter is seen in the modern gala dress of officers in the Spanish Navy.[13] The British Army currently retains the frock coat for ceremonial wear by senior officers of Lieutenant-General rank and above, by officers of the Household Division, by some bandmasters and by holders of certain Royal appointments.[14]

The 19th century polish frock coat with hood and toggle-and-tow fastenings stood model for the overcoat used by the Royal Navy and British Army from 1890 on, known as Duffel coat or Monty coat.[15][16]

Orthodox Jewish wear

In the Lithuanian yeshiva world, many prominent figures wear a black frock coat also known as a kapotteh (accompanied by either a Homburg or fedora hat) as formal wear. In recent years many Sefardi rabbis also wear a similar frock coat. The frock coat amongst non-Hassidic Jews is usually reserved for a rosh yeshiva, (maybe also the mashgiach and other senior rabbis of the yeshiva) and other rabbis such as important communal rabbis and some chief rabbis.

Most married male Lubavitcher Hasidim also don frock coats on Shabbat. All Hasidim also wear a gartel (belt) over their outer coats during prayer services.

Most Hasidim wear long coats called rekelekh during the week, which are often mistaken for frock coats but are really very long suit jackets. On Shabbat, Hasidim wear bekishes, which are usually silk or polyester as opposed to the woollen frock coat. The bekishe and the rekel both lack the waist seam construction of the frock coat. Additionally, bekishes can be distinguished from frock coats by the additional two buttons on front and a lack of a slit in the back.

Part of the slit hem in the back of the frock coat is rounded so as to not require tzitzit. The buttons are usually made to go right over left on most Jewish frock coats, particularly those worn by Hasidic Jews.

In Yiddish, a frock coat is known as a frak, a sirtuk or a kapotteh.

Teddy Boys

The Teddy Boys, a 1950s UK youth movement, named for their use of Edwardian-inspired clothing, briefly revived the frock coat, which they often referred to as a "drape".

Gallery

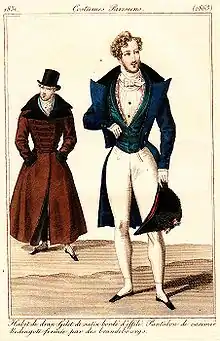

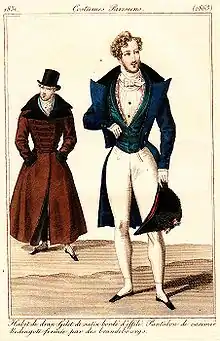

Men's redingote (1813)

Men's redingote (1813) Man's redingote (left) (1831)

Man's redingote (left) (1831) Redingote croisée or double-breasted frock coat (1837)

Redingote croisée or double-breasted frock coat (1837) Andrew Curtin (ca 1860)

Andrew Curtin (ca 1860) Caspar Frederik Wegener (1863)

Caspar Frederik Wegener (1863) The "Terrible Twins" David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill (1907) during the peak of their "radical phase" as social reformers

The "Terrible Twins" David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill (1907) during the peak of their "radical phase" as social reformers Georges Clemenceau (1917)

Georges Clemenceau (1917)

Uniform of Major General Onodera Makoto (c. 1930-1939)

Uniform of Major General Onodera Makoto (c. 1930-1939)

Popular culture

- Doctor Who features frock coats worn by the Doctor during the second, fourth, fifth, sixth, eighth, eleventh, and twelfth incarnations. It also features frock coats worn by some incarnations of the Master.

See also

References

- Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, September 2009

- Condra, Jillian: The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Throughout World History: 1501–1800, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, ISBN 978-0-313-33662-1

- Michael V. Leggiere (2002). Napoleon and Berlin: The Franco-Prussian War in North Germany, 1813. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3399-6.

- Napoleonic Association Prussian Landwehr

- Image of Russian troops in the Crimea

- Major R. M.Barnes, page 247 and plate 23 "A History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army", First Sphere Bools edition 1972

- Howard Lanham - Generalizations regarding the US Army uniforms

- "The Frock Suit | Mass Historia".

- Croonborg (1907). p.30

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "THE STATE FUNERAL OF SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL (NEWS IN COLOUR) - COLOUR IS VERY GOOD". YouTube.

- "McQueen's frock coats and frayed lapels turn heads at London Collections: Men". TheGuardian.com. 18 June 2013.

- "Paul Smith Fall 2018 Menswear Collection". 21 January 2018.

- Jose M. Bueno, plate 38772, "Uniformes de La Infanteria de Marina", Editions Barreira

- Tanner, James (2000), The British Army since 2000, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-78200-593-3 (p. 55)

- "The History of the Duffel Coat". 10 January 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- "Duffel Coat History". 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

Bibliography

- Antongiavanni, Nicholas: The Suit, HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2006. ISBN 0-06-089186-6

- Ashelford, Jane: The Art of Dress: clothing and society 1500-1914, Abrams, New York, 1996. ISBN 0-8109-6317-5

- Baumgarten, Linda: What Clothes Reveal: the language of clothing in colonial and federal America, Yale University Press, New haven, 2002. ISBN 0-300-09580-5

- Black, J. Anderson & Garland, Madge: A History of Fashion, Morrow, New York, 1975. ISBN 0-688-02893-4

- Byrd, Penelope: The Male Image: men's fashion in England 1300-1970. B. T. Batsford Ltd, London, 1979. ISBN 0-7134-0860-X

- Croonborg, Frederick: The Blue Book of Men's Tailoring. Croonborg Sartorial Co., New York and Chicago, 1907

- Cunnington, C. Willett & Cunnington, Phillis: Handbook of English Costume, 3rd ed. Plays Inc. Boston, 1970. ISBN 0-8238-0080-6

- de Marly, Diana: Working Dress: a history of occupational clothing, Batsford, London (UK), 1986; Holmes & Meier (US), 1987. ISBN 0-8419-1111-8

- Devere, Louis: The Handbook of Practical Cutting on the Centre Point System. London, 1866 revised and edited by R. L. Shep. R. L. Shep, Mendocino, California, 1986. ISBN 0-914046-03-9

- Doyle, Robert: The Art of the Tailor. Sartorial Press Publications, Stratford, Ontario, 2005. ISBN 0-9683039-2-7

- Druessedow, Jean L. (editor): Men's Fashion Illustration from the Turn of the Century Reprint. Originally published: New York: Jno J. Mitchell Co. 1910. Dover Publications, 1990 ISBN 0-486-26353-3

- Ettinger, Roseann: Men's Clothes and Fabrics. Schiffer Publishing Ltd, 1998. ISBN 0-7643-0616-2

- Laver, James: Costume and Fashion: a concise history, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, 1969. ISBN 0-500-20266-4

- Minister, Edward: The Complete Guide to Practical Cutting (1853) - Second Edition Vol 1 and 2. Edited by R. L. Shep. R. L. Shep, Mendocino, California, 1993. ISBN 0-914046-17-9

- Peacock, John: Men's Fashion: the complete sourcebook, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, 1996. ISBN 0-500-01725-5

- Salisbury, W. S.: Salisbury's System of Actual Measurement and Drafting for all Styles of Coats upon Geometric Principles. New York 1866. Reprinted in Civil War Gentlemen: 1860 Apparel Arts and Uniforms by R. L. Shep, Mendocino, California, 1994. ISBN 0-914046-22-5

- Tozer, Jane & Levitt, Sarah, Fabric of Society: a century of people and their clothes, 1770-1870, Laura Ashley Press, Carno, Powys, 1983 ISBN 0-9508913-0-4

- Unknown author: The Standard Work on Cutting Men's Garments. 4th ed. Originally pub. 1886 by Jno J Mitchell, New York. ISBN 0-916896-33-1

- Vincent, W. D. F.: The Cutter's Practical Guide. Vol II "All kinds of body coats". The John Williamson Company, London, c. 1893.

- Waugh, Norah: The Cut of Men's Clothes 1600-1900, Routledge, London, 1964. ISBN 0-87830-025-2