Blood alcohol content

Blood alcohol content (BAC), also called blood alcohol concentration or blood alcohol level, is a measurement of alcohol intoxication used for legal or medical purposes;[1] it is expressed as mass of alcohol per volume of blood. For example, a BAC of 0.10 (0.10% or one tenth of one percent) means that there is 0.10 g of alcohol for every 100 mL of blood, which is the same as 21.7 mmol/L.[2] A BAC of 0.0 is sober; in different countries the maximum permitted BAC when driving ranges from about 0.02% to 0.08%; BAC levels over 0.08% are considered impaired; above 0.40% is potentially fatal.[1]

| Blood alcohol content | |

|---|---|

| |

| Synonyms | Blood alcohol concentration, blood ethanol concentration, blood alcohol level, blood alcohol |

| LOINC | 5639-0, 5640-8, 15120-9, 56478-1 |

Effects by alcohol level

As BAC increases, the short-term effects of alcohol become more perceptible. At low levels of impairment (BAC 0.01–0.05%), people may experience mild relaxation and reduced social inhibition, along with impaired judgment and coordination. At moderate levels of impairment (BAC 0.06–0.20%), effects can include emotional swings, impaired vision, hearing, speech, and motor skills. Beginning at a BAC greater than 0.2%, people may experience urinary incontinence, vomiting, and symptoms of alcohol intoxication. At a BAC greater than 0.3%, people may experience total loss of consciousness and show signs of severe alcohol intoxication. A BAC of 0.4% or higher is potentially fatal and can result in a coma or respiratory failure.[3][4]

Estimation

Direct measurement

Blood samples for BAC analysis are typically obtained by taking a venous blood sample from the arm. A variety of methods exist for determining blood-alcohol concentration in a blood sample.[5] Forensic laboratories typically use headspace-gas chromatography combined with mass spectrometry or flame ionization detection,[6] as this method is accurate and efficient.[5] Hospitals typically use enzyme multiplied immunoassay, which measures the co-enzyme NADH. This method is more subject to error but may be performed rapidly in parallel with other blood sample measurements.[7]

By breathalyzer

The amount of alcohol on the breath can be measured, without requiring drawing blood, by blowing into a breathalyzer, resulting in a breath alcohol content (BrAC). The BrAC specifically correlates with the concentration of alcohol in arterial blood, satisfying the equation BACarterial = BrAC × 2251 ± 46. Its correlation with the standard BAC found by drawing venous blood is less strong.[8] Jurisdictions vary in the statutory conversion factor from BrAC to BAC, from 2000 to 2400. Many factors may affect the accuracy of a breathalyzer test,[9] but they are the most common method for measuring alcohol concentrations in most jurisdictions.[10]

By intake

Blood alcohol content can be estimated by a model developed by Swedish professor Erik Widmark in the 1920s.[11] The model corresponds to a pharmacokinetic single-compartment model with instantaneous absorption and zero-order kinetics for elimination. The model is most accurate when used to estimate BAC a few hours after drinking a single dose of alcohol in a fasted state, and can be within 20% CV of the true value.[12][13] It is less accurate for BAC levels below 0.2 g/L (alcohol is not eliminated as quickly as predicted) and consumption with food (overestimating the peak BAC and time to return to zero).[14][15] The equation varies depending on the units and approximations used, but in its simplest form is given by:

where:

- EBAC is the estimated blood alcohol concentration (in g/L)

- A is the mass of alcohol consumed (g).

- T is the amount time during which alcohol was present in the blood (usually time since consumption began), in hours.

- β is the rate at which alcohol is eliminated (g/L/hr); typically 0.15

- Vd is the volume of distribution (L); typically body weight (kg) multiplied by 0.71 L/kg for men and 0.58 L/kg for women

Examples:

- A 80 kg man drinks 2 US standard drinks (3 oz) of 40% ABV vodka, containing 14 grams of ethanol each (28 g total). After two hours:

- A 70 kg woman drinks 63 g of 40% ABV vodka, containing 21 grams of ethanol. After two hours:

The volume of distribution Vd contributes about 15% of the uncertainty to Widmark's equation[16] and has been the subject of much research. It corresponds to the volume of the blood in the body.[11] In his research, Widmark used units of mass (g/kg) for EBAC, thus he calculated the apparent mass of distribution Md or mass of blood in kilograms. He fitted an equation of the body weight W in kg, finding an average rho-factor of 0.68 for men and 0.55 for women. This ρm has units of dose per body weight (g/kg) divided by concentration (g/kg) and is therefore dimensionless. However, modern calculations use weight/volume concentrations (g/L) for EBAC, so Widmark's rho-factors must be adjusted for the density of blood, 1.055 g/mL. This has units of dose per body weight (g/kg) divided by concentration (g/L blood) - calculation gives values of 0.64 L/kg for men and 0.52 L/kg for women, lower than the original.[15] Newer studies have updated these values to population-average ρv of 0.71 L/kg for men and 0.58 L/kg for women. But individual Vd values may vary significantly - the 95% range for ρv is 0.58-0.83 L/kg for males and 0.43-0.73 L/kg for females.[17] A more accurate method for calculating Vd is to use total body water (TBW) - experiments have confirmed that alcohol distributes almost exactly in proportion to TBW. TBW may be calculated using body composition analysis or estimated using anthropometric formulas based on age, height, and weight. Vd is then given by , where is the water content of blood, approximately 0.825 w/v for men and 0.838 w/v for women.[18]

The elimination rate from the blood, β, is perhaps the more important parameter, contributing 60% of the uncertainty to Widmark's equation.[16] Similarly to ρ, its value depends on the units used for blood.[15] β varies 58% by occasion and 42% between subjects; it is thus difficult determine β precisely, and more practical to use a mean and a range of values. The mean values for 164 men and 156 women were 0.148 g/L/h and 0.156 g/L/h respectively. Although statistically significant, the difference between sexes is small compared to the overall uncertainty, so Jones recommends using the value 0.15 for the mean and the range 0.10 - 0.25 g/L/h for forensic purposes, for all subjects.[19] Explanations for the gender difference are quite varied and include liver size, secondary effects of the volume of distribution, and sex-specific hormones.[20] Elaborating on the secondary effects, zero-order kinetics are not an adequate model for ethanol elimination; the elimination rate is better described by Michaelis–Menten kinetics. M-M kinetics are approximately zero-order above a BAC of 0.15-0.20 g/L, but below this value alcohol is eliminated more slowly and the elimination rate more closely follows first-order kinetics. This change in behavior was not noticed by Widmark because he could not analyze low BAC levels.[15] A 2023 study using a more complex two-compartment model with M-M elimination kinetics, with data from 60 men and 12 women, found statistically small effects of gender on maximal elimination rate and excluded them from the final model. Eating food in proximity to drinking increases elimination rate significantly.[21]

In terms of fluid ounces of alcohol consumed and weight in pounds, Widmark's formula can be simply approximated as[11]

for a man or

for a woman, where EBAC and β factors are given as g/dL (% BAC), such as a β factor of 0.0015% BAC per hour.[11]

By standard drinks

The examples above define a standard drink as 0.6 fluid ounces (14 g or 17.7 mL) of ethanol, whereas other definitions exist, for example 10 grams of ethanol.

| Drinks | Sex | Body weight | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 kg 90 lb |

45 kg 100 lb |

55 kg 120 lb |

64 kg 140 lb |

73 kg 160 lb |

82 kg 180 lb |

91 kg 200 lb |

100 kg 220 lb |

109 kg 240 lb | ||

| 1 | Male | – | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Female | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| 2 | Male | – | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Female | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| 3 | Male | – | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Female | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| 4 | Male | – | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Female | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

| 5 | Male | – | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Female | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | |

| 6 | Male | – | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Female | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.11 | |

| 7 | Male | – | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Female | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.13 | |

| 8 | Male | – | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Female | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.15 | |

| 9 | Male | – | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Female | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.17 | |

| 10 | Male | – | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Female | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.19 | |

| Subtract approximately 0.01 every 40 minutes after drinking. | ||||||||||

Other methods

Vitreous (eye) fluid provides an accurate account of blood alcohol concentration in cadavers.[23]

Binge drinking

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) define the term "binge drinking" as a pattern of drinking that brings a person's blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08 grams percent or above. This typically happens when men consume five or more drinks, and when women consume four or more drinks, in about two hours.[24]

Units of measurement

BAC is generally defined as a fraction of weight of alcohol per volume of blood. All countries are based on units of grams per liter, but differ in how this number is expressed as a decimal or percentage. The usual units are listed below. For example, the U.S. uses a concentration unit of 1% w/v (percent mass/volume, equivalent to 10 g/L or 1 g per 100 mL).

| Unit | Dimensions | Equivalent to | Used in |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 percent (%) | 1/100 g/mL = 1 g/dL | 9.43 mg/g, 217.4 mmol/L | United States |

| 1 permille (‰) | 1/1000 g/mL = 1 g/L | 0.943 mg/g, 21.7 mmol/L | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey |

| 1 basis point (‱) | 1/10,000 g/mL = 10 mg/100 mL | 94.3 ppm, 2.17 mmol/L | United Kingdom |

It is also possible to use other definitions, such as grams of alcohol per 100 grams of blood, or grams of alcohol per kilogram of body weight, but these have become uncommon. 1 mL of blood has a mass of approximately 1.06 grams.

Legal limits

For purposes of law enforcement, blood alcohol content is used to define intoxication and provides a rough measure of impairment. Although the degree of impairment may vary among individuals with the same blood alcohol content, it can be measured objectively and is therefore legally useful and difficult to contest in court. Most countries forbid operation of motor vehicles and heavy machinery above prescribed levels of blood alcohol content. Operation of boats and aircraft is also regulated. Some jurisdictions also regulate bicycling under the influence.

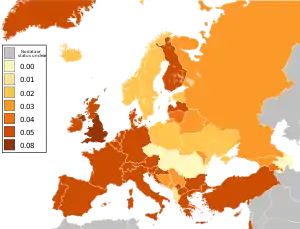

The alcohol level at which a person is considered legally impaired to drive varies by country. The list below gives limits by country. These are typically blood alcohol content limits for the operation of a vehicle.

0%

It is illegal to have any measurable alcohol in the blood while driving in these countries. Most jurisdictions have a tolerance slightly higher than zero to account for false positives and naturally occurring alcohol in the body. Some of the following jurisdictions have a general prohibition of alcohol.

- Australia—Drivers who are learners or holders of a Provisional/Probationary licence

- Bangladesh

- Brazil

- Brunei

- Canada—new drivers undergoing graduated licensing in Ontario, British Columbia,[25] Newfoundland and Labrador and Alberta;[26] drivers under the age of 22 in Manitoba, New Brunswick, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Ontario,[27] Saskatchewan and in Quebec receive a 30-day suspension and 7-day vehicle seizure.[28] Drivers in Alberta who are in the graduated licensing program, regardless of age, are subject to the same 30-day/7-day suspensions/seizure policy.[29]

- Colombia —Zero Alcohol Tolerance law is effective since December 2013 [30][31]

- Czech Republic

- Estonia

- Fiji

- Germany—for learner drivers, all drivers 18–21 and newly licensed drivers of any age for first two years of licence

- Iceland: The limit is 0.00%, although drivers will not be fined with a BAC of below 0.05%.[32]

- Israel—24 µg per 100 mL (0.024%) of breath (penalties only apply above 26 µg per 100 mL (0.026%) of breath following lawsuits about sensitivity of devices used). New drivers, drivers under 24 years of age and commercial drivers 5 µg per 100 mL of breath.(0.005%) [33]

- Hungary*

- Italy—for drivers in their first three years after gaining a driving license

- Japan—drivers under the age of 20 because of not reaching legal drinking age.

- Kuwait

- New Zealand—drivers under the age of 20; drivers convicted of excess breath alcohol may be required to gain a zero-limit license.

- Nepal

- Oman

- Qatar

- Pakistan

- Paraguay

- Romania—beyond 0.04% drivers will not only receive a fine and have their license suspended, the offense will also be added to their criminal records.

- Russian Federation—0% introduced in 2010, but discontinued in September 2013[34]

- Saudi Arabia

- Scotland

- Slovakia

- South Africa

- Uruguay[35]

- United Arab Emirates

- Vietnam

0.02%

- China

- Faroe Islands

- Netherlands (for drivers in their first five years after gaining a driving license)[36]

- Norway (road vehicles and sea vessels over 15 m),[37] alternatively 0.1 mg/L of breath.

- Hungary*

- Poland (0.02% – 0.05% is a petty offence, over 0.05% is a criminal offence)

- Puerto Rico

- Russia (0.018% since September 2013[34])

- Serbia

- Sweden

- Ukraine

- United States—drivers under the age of 21 must have 0.02% or less on the federal level; however, most states have Zero Tolerance laws emplaced. Otherwise the limit is 0.08%, except in Utah, where it is 0.05%.

0.03%

- Belarus

- Bosnia and Herzegovina (0.031%)

- Chile

- India

- Japan[38]

- Korea

0.04%

- Lithuania (0.00% for car drivers in their first two years after gaining a driving license, motorcycle and truck drivers)

0.05%

- Argentina: 0.02% for motorbikes, 0.00% for truck, taxi, and bus drivers, 0.00% in the provinces of Cordoba and Salta

- Australia: 0.00% for Australian Capital Territory learner, provisional and convicted DUI drivers (changed down from 0.02% on December 1, 2010), 0.02% for truck/bus/taxi, 0.00% for learner drivers, provisional/probationary drivers (regardless of age), truck and bus drivers, driving instructors and DUI drivers in all other states

- Austria: no limit for pedestrians; 0.08% for cycling; 0.05% generally for cars <7.5 t (driving licence B) and motorbikes (A); but 0,01% during learning (for driver and teacher or L17-assistant). During probation period (at least the first 3 years) or up to the age of 21, when license was handed out after July 1, 2017, when older (at least the first 2 years) or up to the age of 20 (A1, AM, L17, F), trucks (C >7.5 t), bus (D), drivers of taxi and public transport[39][40]

- Belgium (also for cyclists)

- Bulgaria

- Canada: Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, Manitoba, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick—provincial offence. Drivers have not committed a criminal offense, however a 3-day licence suspension and 3-day vehicle seizure occurs.

- Costa Rica

- Croatia: professional drivers, driving instructors and drivers of the vehicle categories C1, C1+E, C, C+E, D, D+E and H; the limit for other drivers is 0.50 mg/g, but they do get an additional separate fine if they cause an accident while having a blood alcohol level between 0 and 0,50 mg/g[41]

- Denmark (excl. Faroe Islands)

- Finland

- France: 0.025% for bus drivers. Between 0.05% and 0.08%, drivers can be fined €135 and have six points removed from their licence. Above 0.08%, the punishment is more severe with possible imprisonment of up to two years, heavy fines and licence suspension.[42]

- Germany (0.0% for learner drivers, all drivers 18–21 and newly licensed drivers of any age for first two years of licence; also, if the BAC exceeds 0.03%, driving is illegal if the driver is showing changes in behavior ("Relative Fahruntüchtigkeit"))

- Greece (0.02% for drivers in their first two years after gaining a driving license)

- Hong Kong

- Ireland: 0.02% for professional, learner and novice drivers (drivers in their first two years after gaining a driving license)[43]

- Israel: 24 µg per 100 mL (0.024%) of breath (penalties only apply above 26 µg per 100 mL (0.026%) of breath due to lawsuits about sensitivity of devices used). This is equivalent to a BAC of 0.05. New drivers, drivers under 24 years of age and commercial drivers 5 µg per 100 mL of breath. This is equivalent to a BAC of 0.01.[33]

- Italy: 0.00% for drivers in their first three years after gaining a driving license

- Latvia: 0.02% for drivers in their first two years after gaining a driving license

- Luxembourg

- Malta: 0.02% for drivers with a probationary driving licence and drivers of commercial vehicles, and 0.00% for drivers of buses, coaches and other passenger carrying vehicles.[44]

- Mauritius[45]

- Netherlands: 0.02% for drivers in their first five years after gaining a driving license[36]

- New Zealand

- North Macedonia: 0.00% for drivers in their first two years after gaining a driving license

- Peru

- Philippines: 0.00% for taxicab and public transport drivers[46]

- Portugal: 0.02% for drivers holding a driver's licence for less than three years, professional drivers, and drivers of taxis, heavy vehicles, emergency vehicles, public transport of children and carrying dangerous goods.

- Scotland: Scotland's drink-drive limit was reduced, by law, on 5 December 2014 from 0.08 to any of the following: 22 mcg of alcohol in 100 mL of breath, 50 mg of alcohol in 100 mL of blood, or 67 mg of alcohol in 100 mL of urine[47]

- Slovenia: 0.00% for drivers in their first two years after gaining a drivers licence, drivers under 21 and professional drivers, such as buses, trucks.

- Spain (0.03% for drivers in their first two years after gaining a driving license and common carriers, such as buses and trucks)

- Switzerland (0.00% for learner drivers, drivers which are in their first three years after gaining a drivers licence and for driving instructors)[48]

- Thailand: 0.02% for drivers who (1) hold a probationary driving licence or; (2) have a licence for different vehicle category or; (3) are under 20 years old or; (4) are disqualified and attempt to drive illegally[49]

- Taiwan: breath alcohol limit decreased from 0.025 to 0.015 from 13 June 2013

- Turkey

- United States – Utah[50]

0.06%

- The Bahamas[51]

0.07%

- Honduras

0.08%

- Canada[52]

- England and Wales;[47] 0.02% for operators of fixed-wing aircraft

- Liechtenstein

- Malaysia: 0.00 for Probationary Driving Licence holders

- Mexico

- New Zealand: Criminal offence

- Norway: legal limit for sea vessels under 15 m[53]

- Northern Ireland: The government of Northern Ireland intends to reduce the general limit to 0.05%.[54]

- Puerto Rico: For drivers 18 years and older

- Singapore[55]

- Trinidad and Tobago

- United States: Every state imposes mandatory penalties for operating a vehicle with a BAC level of 0.08% or greater,[56][57] except Utah where the limit is 0.05%.[58] Even below those levels drivers can have civil liability and other criminal guilt (e.g., in Arizona driving impairment to any degree caused by alcohol consumption can be a civil or criminal offense in addition to other offenses at higher blood alcohol content levels). Drivers under 21 (the most common U.S. legal drinking age) are held to stricter standards under zero tolerance laws adopted in varying forms in all states: commonly 0.01% to 0.05%. See Alcohol laws of the United States by state. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration: 0.04% for drivers of a commercial vehicle requiring a commercial driver's license[59] and 0.01% for operators of common carriers, such as buses.[60]

0.10%

Breath alcohol content

In certain countries, alcohol limits are determined by the breath alcohol content (BrAC), not to be confused with blood alcohol content (BAC).

- In Greece, the BrAC limit is 250 micrograms of alcohol per litre of breath. The limit in blood is 0.50 g/L. The BrAC limit for drivers in their first two years after gaining a driving license and common carriers are more restricted to 100 micrograms per litre of breath.

- In Hong Kong, the BrAC limit is 220 micrograms per litre of breath (as well as other defined limits)

- In The Netherlands and Finland, the BrAC limit is 220 micrograms of alcohol per litre of breath (μg/L, colloquially known as "ugl" because some types of breathalyzer show the μ as 'u' due to screen size limitations).

- In New Zealand, the BrAC limit is 250 micrograms of alcohol per litre of breath for those aged 20 years or over, and zero (meaning illegal to have any measurable breath alcohol content) for those aged under 20 years.[62]

- In Singapore, the BrAC limit is 350 micrograms of alcohol per litre of breath.[55]

- In Spain the BrAC limit is 250 micrograms of alcohol per litre of breath and 150 micrograms per litre of breath for drivers in their first two years after gaining a driving license and common carriers.

- In England and Wales the BrAC limit is 350 micrograms of alcohol per litre of breath (as well as the above defined blood alcohol content).

- In Scotland the BrAC limit is 220 micrograms of alcohol per litre of breath (as well as the above defined blood alcohol content).

- In Trinidad and Tobago the BrAC limit is 35 micrograms of alcohol per 100 millilitres of breath (as well as the above defined blood alcohol content).

Other limitation schemes

- For South Korea, the penalties for different blood alcohol content levels include

- 0.01–0.049 = No penalty

- 0.05–0.09 = 100 days license suspension

- >0.10 = Cancellation of car license.

Test assumptions

After fatal accidents, it is common to check the blood alcohol levels of involved persons. However, soon after death, the body begins to putrefy, a biological process which produces ethanol. This can make it difficult to conclusively determine the blood alcohol content in autopsies, particularly in bodies recovered from water.[63][64][65][66] For instance, following the Moorgate tube crash, the driver had a blood alcohol concentration of 80 mg/100 mL, but it could not be established how much of this could be attributed to natural decomposition.

Extrapolation

Retrograde extrapolation is the mathematical process by which someone's blood alcohol concentration at the time of driving is estimated by projecting backwards from a later chemical test. This involves estimating the absorption and elimination of alcohol in the interim between driving and testing. The rate of elimination in the average person is commonly estimated at 0.015 to 0.020 grams per deciliter per hour (g/dL/h),[67] although again this can vary from person to person and in a given person from one moment to another. Metabolism can be affected by numerous factors, including such things as body temperature, the type of alcoholic beverage consumed, and the amount and type of food consumed.

In an increasing number of states, laws have been enacted to facilitate this speculative task: the blood alcohol content at the time of driving is legally presumed to be the same as when later tested. There are usually time limits put on this presumption, commonly two or three hours, and the defendant is permitted to offer evidence to rebut this presumption.

Forward extrapolation can also be attempted. If the amount of alcohol consumed is known, along with such variables as the weight and sex of the subject and period and rate of consumption, the blood alcohol level can be estimated by extrapolating forward. Although subject to the same infirmities as retrograde extrapolation—guessing based upon averages and unknown variables—this can be relevant in estimating BAC when driving and/or corroborating or contradicting the results of a later chemical test.

Metabolism

Alcohol is absorbed throughout the gastrointestinal tract, but more slowly in the stomach than in the small or large intestine. For this reason, alcohol consumed with food is absorbed more slowly, because it spends a longer time in the stomach.[68] Furthermore, alcohol dehydrogenase is present in the stomach lining. After absorption, the alcohol passes to the liver through the hepatic portal vein, where it undergoes a first pass of metabolism before entering the general bloodstream.[69]

Alcohol is removed from the bloodstream by a combination of metabolism, excretion, and evaporation. Alcohol is metabolized mainly by the group of six enzymes collectively called alcohol dehydrogenase. These convert the ethanol into acetaldehyde (an intermediate more toxic than ethanol). The enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase then converts the acetaldehyde into non-toxic acetic acid.

Many physiologically active materials are removed from the bloodstream (whether by metabolism or excretion) at a rate proportional to the current concentration, so that they exhibit exponential decay with a characteristic half-life (see pharmacokinetics). This is not true for alcohol, however. Typical doses of alcohol actually saturate the enzymes' capacity, so that alcohol is removed from the bloodstream at an approximately constant rate. This rate varies considerably between individuals. Another sex-based difference is in the elimination of alcohol. People under 25, women,[70] or people with liver disease may process alcohol more slowly. Falsely high BAC readings may be seen in patients with kidney or liver disease or failure.

Such persons also have impaired acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, which causes acetaldehyde levels to peak higher, producing more severe hangovers and other effects such as flushing and tachycardia. Conversely, members of certain ethnicities that traditionally did not use alcoholic beverages have lower levels of alcohol dehydrogenases and thus "sober up" very slowly but reach lower aldehyde concentrations and have milder hangovers. The rate of detoxification of alcohol can also be slowed by certain drugs which interfere with the action of alcohol dehydrogenases, notably aspirin, furfural (which may be found in fusel alcohol), fumes of certain solvents, many heavy metals, and some pyrazole compounds. Also suspected of having this effect are cimetidine, ranitidine, and acetaminophen (paracetamol).

Currently, the only known substance that can increase the rate of alcohol metabolism is fructose. The effect can vary significantly from person to person, but a 100 g dose of fructose has been shown to increase alcohol metabolism by an average of 80%. Fructose also increases false positives of high BAC readings in anyone with proteinuria and hematuria, due to kidney-liver metabolism.[71]

The peak of blood alcohol level (or concentration of alcohol) is reduced after a large meal.[68]

Highest levels

There have been reported cases of blood alcohol content higher than 1%:

- In 1982, a 24-year-old woman was admitted to the UCLA emergency room with a serum alcohol content of 1.51%, corresponding to a blood alcohol content of 1.33%. She was alert and oriented to person and place and survived.[72] Serum alcohol concentration is not equal to nor calculated in the same way as blood alcohol content.[73]

- In 1984, a 30-year-old man survived a blood alcohol concentration of 1.5% after vigorous medical intervention that included dialysis and intravenous therapy with fructose.[74]

- In 1995, a man from Wrocław, Poland, caused a car accident near his hometown. He had a blood alcohol content of 1.48%; he was tested five times, with each test returning the same reading. He died a few days later of injuries from the accident.[75]

- In 2004, an unidentified Taiwanese woman died of alcohol intoxication after immersion for twelve hours in a bathtub filled with 40% ethanol. Her blood alcohol content was 1.35%. It was believed that she had immersed herself as a response to the SARS epidemic.[76]

- In South Africa, a man driving a Mercedes-Benz Vito light van containing 15 sheep allegedly stolen from nearby farms was arrested on December 22, 2010, near Queenstown in Eastern Cape. His blood had an alcohol content of 1.6%. Also in the vehicle were five boys and a woman, who were also arrested.[77]

- On 26 October 2012, a man from Gmina Olszewo-Borki, Poland, who died in a car accident, recorded a blood alcohol content of 2.23%; however, the blood sample was collected from a wound and thus possibly contaminated.[75]

- On 26 July 2013 a 40-year-old man from Alfredówka, Poland, was found by Municipal Police Patrol from Nowa Dęba lying in the ditch along the road in Tarnowska Wola. At the hospital, it was recorded that the man had a blood alcohol content of 1.374%. The man survived.[78][79]

References

Citations

- "Blood Alcohol Level". MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. 3 December 2020.

- McCune, Anne (2015). ABC of Alcohol. John Wiley & Sons. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-118-54396-2.

- Dasgupta, Amitava (1 January 2017), "Alcohol a double-edged sword: Health benefits with moderate consumption but a health hazard with excess alcohol intake", in Dasgupta, Amitava (ed.), Alcohol, Drugs, Genes and the Clinical Laboratory: An Overview for Healthcare and Safety Professionals, Academic Press, pp. 1–21, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-805455-0.00001-4, ISBN 978-0-12-805455-0, retrieved 24 May 2023

- Haghparast, Parna; Tchalikian, Tina N. (1 January 2022), "Alcoholic beverages and health effects", Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, Elsevier, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-824315-2.00244-x, ISBN 978-0-12-801238-3, retrieved 24 May 2023

- Dubowski, Kurt M. (1 November 1980). "Alcohol Determination in the Clinical Laboratory". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 74 (5): 747–750. doi:10.1093/ajcp/74.5.747.

- Zamengo, Luca; Tedeschi, Gianpaola; Frison, Giampietro; Griffoni, Carlo; Ponzin, Diego; Jones, Alan Wayne (1 February 2019). "Inter-laboratory proficiency results of blood alcohol determinations at clinical and forensic laboratories in Italy". Forensic Science International. 295: 213–218. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.12.018. ISSN 0379-0738.

- "Hospital Blood Alcohol Lab Results: Are They Forensically Reliable?". Law Offices of Christopher L. Baxter. 30 April 2020.

- Lindberg, L.; Brauer, S.; Wollmer, P.; Goldberg, L.; Jones, A.W.; Olsson, S.G. (May 2007). "Breath alcohol concentration determined with a new analyzer using free exhalation predicts almost precisely the arterial blood alcohol concentration". Forensic Science International. 168 (2–3): 200–207. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.07.018.

- Jones, AW; Cowan, JM (3 August 2020). "Reflections on variability in the blood-breath ratio of ethanol and its importance when evidential breath-alcohol instruments are used in law enforcement". Forensic sciences research. 5 (4): 300–308. doi:10.1080/20961790.2020.1780720. PMID 33457048.

- Williams, Paul M. (1 December 2018). "Current defence strategies in some contested drink-drive prosecutions: Is it now time for some additional statutory assumptions?". Forensic Science International. 293: e5–e9. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.09.030.

- Ed Kuwatch. "Fast Eddie's 8/10 Method of Hand Calculating Blood Alcohol Concentration: A Simple Method For Using Widmark's Formula". Archived from the original on 2 December 2003.

- Zuba, Dariusz; Piekoszewski, Wojciech (2004). "Uncertainty in Theoretical Calculations of Alcohol Concentration". Proc. 17th Internat. Conf. on Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety.

- Gullberg, Rod G. (October 2007). "Estimating the uncertainty associated with Widmark's equation as commonly applied in forensic toxicology". Forensic Science International. 172 (1): 33–39. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.11.010. PMID 17210238.

- Searle, John (January 2015). "Alcohol calculations and their uncertainty". Medicine, Science and the Law. 55 (1): 58–64. doi:10.1177/0025802414524385. PMID 24644224.

- Jones, AW (July 2011). "Pharmacokinetics of Ethanol - Issues of Forensic Importance". Forensic science review. 23 (2): 91–136. PMID 26231237.

- Maskell, Peter D.; Cooper, Gail A. A. (September 2020). "The Contribution of Body Mass and Volume of Distribution to the Estimated Uncertainty Associated with the Widmark Equation". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 65 (5): 1676–1684. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.14447.

- Maskell, Peter D.; Heymsfield, Steven B.; Shapses, Sue; Limoges, Jennifer F. (September 2023). "Population ranges for the volume of distribution ( V_d ) of alcohol for use in forensic alcohol calculations". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 68 (5): 1843–1845. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.15317.

- Maskell, Peter D.; Jones, A. Wayne; Heymsfield, Steven B.; Shapses, Sue; Johnston, Atholl (November 2020). "Total body water is the preferred method to use in forensic blood-alcohol calculations rather than ethanol's volume of distribution". Forensic Science International. 316: 110532. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110532.

- Jones, Alan Wayne (July 2010). "Evidence-based survey of the elimination rates of ethanol from blood with applications in forensic casework". Forensic Science International. 200 (1–3): 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.02.021.

- Dettling, A.; Skopp, G.; Graw, M.; Haffner, H.-Th. (May 2008). "The influence of sex hormones on the elimination kinetics of ethanol". Forensic Science International. 177 (2–3): 85–89. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.11.002.

- Büsker, Sören; Jones, Alan Wayne; Hahn, Robert G.; Taubert, Max; Klotz, Ulrich; Schwab, Matthias; Fuhr, Uwe (June 2023). "Population Pharmacokinetics as a Tool to Reevaluate the Complex Disposition of Ethanol in the Fed and Fasted States". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 63 (6): 681–694. doi:10.1002/jcph.2205.

- BAC Charts Archived June 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine from Virginia Tech

- Honey, Donna; Caylor, Curtis; Luthi, Ruth; Kerrigan, Sarah (July 2005). "Comparative alcohol concentrations in blood and vitreous fluid with illustrative case studies". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 29 (5): 365–369. doi:10.1093/jat/29.5.365. ISSN 0146-4760. PMID 16105262.

- "Quick Stats: Binge Drinking." The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 2008..

- "The Various Alcohol and Drug Related Prohibitions and Suspensions – Prohibitions and Suspensions – RoadSafetyBC". Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- Alberta, Government of (16 November 2011). "Alberta's approach to impaired driving". www.transportation.alberta.ca. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Newsroom : Keeping Drivers Safe". news.ontario.ca. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- Bergeron, Patrice (17 February 2012). "Tolérance zéro pour les conducteurs de moins de 21 ans". La Presse.

- "Alberta Zero Alcohol Tolerance Program (Graduated Driver's Licence)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- "Tolerancia cero: ni una cerveza si va a conducir". eltiempo.com. 21 December 2013.

- "Presidencia de la republica" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Ólafsdóttir, Hildigunnur (February 2007). "Trends in Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol-Related Harms in Iceland". Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 24 (1_suppl): 47–60. doi:10.1177/1455072507024001S06. ISSN 1455-0725.

- "Alcohol and Driving". Ministry of Transport. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- "Russian drivers to be allowed to have slight alcohol content in blood". Itar-tass. 26 July 2013.

- "Alcohol cero rige a partir de 2016". 29 December 2015.

- "Alcohol". 11 December 2009.

- "/d: LOV-1965-06-18-4 :d/ Lov om vegtrafikk (vegtrafikkloven)".

- http://www.npa.go.jp/policies/application/license_renewal/pdf/english.pdf Archived 17 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine [outdated, invalid] https://englishlawyersjapan.com/what-is-the-legal-limit-for-drunk-driving-in-japan-and-what-happens-if-i-drive-under-the-influence/ [11/2021] The breath alcohol concentration limit for driving in Japan is 0.15 mg/L, which, assuming a breath alcohol to blood alcohol ratio of 1:2,100, is roughly equivalent to a BAC of 0.0315%. The penalties become even more severe at 0.25 mg/L, which is roughly equivalent to a BAC of 0.0525%.

- https://www.help.gv.at/Portal.Node/hlpd/public/content/4/Seite.042000.html Alkohol am Steuer, HELP.gv.at, of 19. January 2013, retr. 22. April 2013

- http://www.verkehrspsychologie.at/gesetzliche_grundlagen_fuehrerscheinentzug.htm Archived 18 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine Gesetzliche Grundlagen für den Führerscheinentzug (Alkohol), verkehrspsychologie.at, AAP – Angewandte Psychologie und Forschung GmbH, Wien, retr. 22. April 2013

- "Driving law (hr)".

- "L'alcool au volant" [Alcohol and Driving] (in French). Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- "How alcohol affects your ability to drive". www2.hse.ie. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- "LEĠIŻLAZZJONI MALTA".

- "The Mauritius Police Force - Safety Driving".

- "BAC and BrAC Limits – International Alliance for Responsible Drinking". International Alliance for Responsible Drinking. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- "Drink-drive limit". gov.uk. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Quoi de neuf en 2014 ?". Archived from the original on 16 January 2014.

- ราชกิจจานุเบกษา, กฎกระทรวงฉบับที่ ๒๑ (พ.ศ. ๒๕๖๐) ออกตามความในพระราชบัญญัติจราจรทางบก พ.ศ. ๒๕๒๒, เล่ม ๑๓๔ ตอนที่ ๕๙ ก, ๓๑ พฤษภาคม ๒๕๖๐ (Ministerial Regulation on Legal Alcohol Limit for Drivers, 2017)

- "Utah's New Law Against Drinking and Driving". LLU Institute for Health Policy Leadership. 25 February 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- "Driving Under the Influence Unit". Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- "Drinking and Driving: SAAQ". Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- "/d: LOV-1998-06-26-47 :d/ Lov om fritids- og småbåter".

- "DOE – Biggest shake up in drink driving laws for forty years – Attwood". Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- Driving In Singapore – Home Archived February 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Why Police Use A Breathalyzer Test Over A Blood Test For DUI & DWI Charges". Fight DUI Charges Law. 5 December 2021.

- National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. http://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/Blood_Alcohol_Concentration_Limits_Adult_Operators_of_Noncommercial_Motor_Vehicles.html. Accessed on February 01, 2013.

- "New .05 BAC Law".

- "Commercial Driver's License Program". Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. 2 January 2014.

- "18 U.S.C. § 343: US Code – Section 343: Presumptions". Findlaw.

- "Κώδικας Οδικής Κυκλοφορίας (Κ.Ο.Κ.)" [Highway Code] (PDF) (in Greek). 11 April 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- "Alcohol and drug limits". Driving Tests Resources. 25 July 2014.

- Kugelberg, Fredrik C.; Jones, Alan Wayne (5 January 2007). "Interpreting results of ethanol analysis in postmortem specimens: A review of the literature". Forensic Science International. 165 (1): 10–27. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.05.004. PMID 16782292. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Xie, Y.; Deng, Z. H. (2010). "Analysis of alcohol mass concentration in corpse blood". Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 26 (1): 59–63. PMID 20232748.

- Felby, S.; Nielsen, E. (1993). "Postmortem blood alcohol concentration". Blutalkohol. 30 (4): 244–250. PMID 8373563.

- Cowan, Dallas M.; Maskrey, Joshua R.; Fung, Ernest S.; Woods, Tyler A.; Stabryla, Lisa M.; Scott, Paul K.; Finley, Brent L. (2016). "Best-practices approach to determination of blood alcohol concentration (BAC) at specific time points: Combination of ante-mortem alcohol pharmacokinetic modeling and post-mortem alcohol generation and transport considerations". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 78: 24–36. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.03.020. PMID 27041394.

- Montgomery, Mark R.; Reasor, Mark J. (1992). "Retrograde extrapolation of blood alcohol data: An applied approach". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 36 (4): 281–92. doi:10.1080/15287399209531639. PMID 1507264.

- "Absorption Rate Factors". BHS.UMN.edu. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

When food is ingested, the pyloric valve at the bottom of the stomach will close in order to hold food in the stomach for digestion and thus keep the alcohol from reaching the small intestine. The larger the meal and closer in time to drinking, the lower the peak of alcohol concentration; some studies indicate up to a 20% reduction in peak blood alcohol level.

Stress causes the stomach to empty directly into the small intestine, where alcohol is absorbed even faster.

Liquor mixed with soda or other bubbly drinks speeds up the passage of alcohol from the stomach to the small intestine, which increases the speed of absorption. - Alan J.Buglass, ed. (2011). Handbook of alcoholic beverages : technical, analytical and nutritional aspects. Chichester: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-97665-4. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Thomasson, Holly R. (2002). "Gender Differences in Alcohol Metabolism". Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol. 12. pp. 163–72. doi:10.1007/0-306-47138-8_9. ISBN 978-0-306-44921-5. PMID 7624539.

- Fructose & ethanol

- Carpenter, Thorne M.; Lee, Robert C (1937). "The effect of fructose on the metabolism of ethyl alcohol in man". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 60 (3). Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Tygstrup, Niels; Winkler, Kjeld; Lundquist, Frank (1 May 1965). "The Mechanism of the Fructose Effect on the Ethanol Metabolism of the Human Liver*". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 44 (5): 817–830. doi:10.1172/JCI105194. PMC 292558. PMID 14276139.

- Patel, AR; Paton, AM; Rowan, T; Lawson, DH; Linton, AL (August 1969). "Clinical studies on the effect of laevulose on the rate of metabolism of ethyl alcohol". Scottish Medical Journal. 14 (8): 268–71. doi:10.1177/003693306901400803. PMID 5812044. S2CID 3067691.

- Lowenstein, LM; Simone, R; Boulter, P; Nathan, P (14 September 1970). "Effect of fructose on alcohol concentrations in the blood in man". JAMA. 213 (11): 1899–901. doi:10.1001/jama.1970.03170370083021. PMID 4318655.

- Pawan, GL (September 1972). "Metabolism of alcohol (ethanol) in man". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 31 (2): 83–9. doi:10.1079/pns19720020. PMID 4563296.

- Thieden, HI; Grunnet, N; Damgaard, SE; Sestoft, L (October 1972). "Effect of fructose and glyceraldehyde on ethanol metabolism in human liver and in rat liver". European Journal of Biochemistry. 30 (2): 250–61. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb02093.x. PMID 4145889.

- Soterakis, J; Iber, FL (March 1975). "Increased rate of alcohol removal from blood with oral fructose and sucrose". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 28 (3): 254–7. doi:10.1093/ajcn/28.3.254. PMID 1119423.

- Rawat, AK (February 1977). "Effects of fructose and other substances on ethanol and acetaldehyde metabolism in man". Research Communications in Chemical Pathology and Pharmacology. 16 (2): 281–90. PMID 847286.

- Iber, FL (September 1977). "The effect of fructose on alcohol metabolism". Archives of Internal Medicine. 137 (9): 1121. doi:10.1001/archinte.137.9.1121. PMID 901079.

- Bode, JC; Bode, C; Thiele, D (1 February 1979). "Alcohol metabolism in man: effect of intravenous fructose infusion on blood ethanol elimination rate following stimulation by phenobarbital treatment or chronic alcohol consumption". Klinische Wochenschrift. 57 (3): 125–30. doi:10.1007/bf01476052. PMID 439778. S2CID 8813046.

- Sprandel, U; Tröger, HD; Liebhardt, EW; Zöllner, N (1980). "Acceleration of ethanol elimination with fructose in man". Nutrition & Metabolism. 24 (5): 324–30. doi:10.1159/000176278. PMID 7443107.

- Meyer, BH; Müller, FO; Hundt, HK (6 November 1982). "The effect of fructose on blood alcohol levels in man". South African Medical Journal (Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde). 62 (20): 719–21. PMID 6753183.

- Crownover, BP; La Dine, J; Bradford, B; Glassman, E; Forman, D; Schneider, H; Thurman, RG (March 1986). "Activation of ethanol metabolism in humans by fructose: importance of experimental design". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 236 (3): 574–9. PMID 3950864.

- Mascord, D; Smith, J; Starmer, GA; Whitfield, JB (1991). "The effect of fructose on alcohol metabolism and on the [lactate]/[pyruvate] ratio in man". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 26 (1): 53–9. PMID 1854373.

- Onyesom, I; Anosike, EO (June 2004). "Oral fructose-induced changes in blood ethanol oxidokinetic data among healthy Nigerians". The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 35 (2): 476–80. PMID 15691159.

- Uzuegbu, UE; Onyesom, I (June 2009). "Fructose-induced increase in ethanol metabolism and the risk of Syndrome X in man". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 332 (6): 534–8. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2009.01.007. PMID 19520316.

- Johnson, R (1982). "Survival After a Serum Ethanol Concentration of 11/2%". The Lancet. 320 (8312): 1394. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(82)91285-5. PMID 6129476. S2CID 27551241.

- Labianca, Dominick A. (2002). "Conversion of Serum-Alcohol Concentrations to Corresponding Blood-Alcohol Concentrations". Journal of Chemical Education. 79 (7): 803. Bibcode:2002JChEd..79..803L. doi:10.1021/ed079p803.

- O'Neill, Shane; Tipton, KF; Prichard, JS; Quinlan, A (1984). "Survival After High Blood Alcohol Levels: Association with First-Order Elimination Kinetics". Archives of Internal Medicine. 144 (3): 641–2. doi:10.1001/archinte.1984.00350150255052. PMID 6703836.

- Łuba, Marcin (24 October 2012). "Śmiertelny rekord: Kierowca z powiatu ostrołęckiego miał 22 promile alkoholu! Zginął w wypadku". eOstroleka.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- Wu, Yen-Liang; Guo, How-Ran; Lin, Hung-Jung (2005). "Fatal alcohol immersion during the SARS epidemic in Taiwan". Forensic Science International. 149 (2–3): 287. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.06.014. PMC 7131152. PMID 15749375.

- Mashaba, Sibongile (24 December 2010). "Drunkest driver in SA arrested". Sowetan. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- "Miał 13,74 promila alkoholu we krwi. I przeżył. Rekord świata?" [He had 13.74 blood alcohol levels. And he survived. World record?]. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- "Informacje".

General and cited references

- Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. Science and Technology Department. The Handy Science Answer Book. Pittsburgh: The Carnegie Library, 1997. ISBN 978-0-7876-1013-5.

- Perham, Nick; Moore, Simon C.; Shepherd, Jonathan; Cusens, Bryany (2007). "Identifying drunkenness in the night-time economy". Addiction. 102 (3): 377–80. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01699.x. PMID 17298644.

- Taylor, L., and S. Oberman. Drunk Driving Defense, 6th edition. New York: Aspen Law and Business, 2006. ISBN 978-0-7355-5429-0.