Testament of Bolesław III Wrymouth

The last will and testament of the Piast duke Bolesław III Wrymouth of Poland,[1] established rules for governance of the Polish kingdom by his four surviving sons after his death. By issuing it, Bolesław planned to guarantee that his heirs would not fight among themselves, and would preserve the unity of his lands under the Piast dynasty. However, he failed; soon after his death his sons fought each other, and Poland entered a period of fragmentation lasting about 200 years.[2]

Provisions

Bolesław III issued the document around January 1115 (between the birth of his son Leszek and the rebellion of Skarbimir); it would be enacted upon his death in 1138.[3]

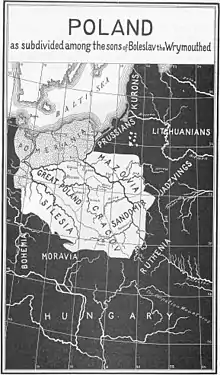

Bolesław divided the country into five principalities:

- the Seniorate Province (or Duchy of Kraków), composed of western Lesser Poland, the eastern parts of Greater Poland, western Kuyavia and the lands of Sieradz, assigned to Bolesław's eldest son and future High Duke Władysław II, as well as the lands of Łęczyca which were held by Bolesław's widow Salomea of Berg for life and to revert to the Seniorate Province upon her death;

- the Silesian Province (or Duchy of Silesia), comprising Silesia, also assigned to Władysław II;

- the Masovian Province (or Duchy of Masovia), composed of Masovia proper and eastern Kuyavia, assigned to Bolesław's III second son Bolesław IV the Curly;

- the Greater Poland Province (or Duchy of Greater Poland), composed of the remaining western parts of Greater Poland, assigned to the third son Mieszko III the Old,

- the Sandomierz Province (or Duchy of Sandomierz), composed of eastern Lesser Polish territories centered around the city of Sandomierz, assigned to the fourth son Henry of Sandomierz.

The youngest son Casimir II the Just was not assigned any province; it is speculated that he was born after Bolesław's death, or that he was destined for a religious career.

The senioral principle established in the testament stated that at all times the eldest member of the dynasty (the Senior Prince, the Princeps or High Duke) was to have supreme power over the rest (Dux, the Dukes) and was also to control an indivisible "seniorate province" : a vast strip of land running north–south down the middle of Poland, with Kraków (the Kingdom of Poland's capital) its chief city. The Senior's prerogatives also included control over the Pomeranian vassals in Pomerelia, as a fief. The Senior was tasked with defense of borders, the right to have troops in provinces of other Dukes, carrying out foreign policy, supervision over the clergy (including the right to nominate bishops and archbishops), and minting of currency.

Aftermath

The senioral principle was soon broken, with Władysław II attempting to increase his power and his younger half-brothers opposing him. After initial success (taking over the Łęczyca Land after the death of Salomea), he was eventually defeated and expelled from Poland in 1146. With the help of Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa his sons managed to retain the Silesian Province in 1163, losing the Seniorate, which had passed to their uncle Bolesław IV. This led to a period of nearly 200 years of Poland's feudal fragmentation; the estrangement of the Silesian Piasts deepening after the death of Duke Henry II the Pious at the disastrous Battle of Legnica in 1241.

The Polish throne at Kraków remained contested between the descendants of Bolesław's III sons. Once Duke Władysław I the Elbow-high, a descendant of Casimir II the Just, was crowned King of Poland in 1320, he would reign on a smaller dominium, with Pomerelia lost to the State of the Teutonic Order and Silesia mostly vassalized by the Kingdom of Bohemia.

See also

- Dukes of Poland

- Principate

- Seniorate

References

- Norman Davies, God's Playground, pages: xxvii

- Norman Davies, God's Playground, page: 60

- Norman Davies, God's Playground, pages: 53 accessed 7 January 2008

Further reading

- Bieniak J., Powstanie księstwa opolsko-raciborskiego jako wyraz przekształcania się Polski w dzielnicową poliarchię, in: Sacra Silentii Provintia. 800 lat dziedzicznego księstwa opolskiego (1202-2002), Opole 2003, pp. 37–81.

- Bieniak J., Polska elita polityczna XII wieku, cz. I, (w:) Społeczeństwo Polski średniowiecznej t. II, Warszawa 1982, s. 29–61,

- Buczek K., Jeszcze o testamencie Bolesława Krzywoustego, „Przegląd Historyczny” 60, 1969, z. 4, s. 621–637,

- Dowiat J., Polska – państwem średniowiecznej Europy, Warszawa 1968, s. 225–229,

- Dalewski Z., Władza Przestrzeń Ceremoniał. Miejsce i uroczystość stanowienia władcy w Polsce średniowiecznej do końca XIV w, Warszawa 1996, s. 72–85.

- Dworsatschek M., Władysław II Wygnaniec, Wrocław 1998, s. 13, 36–51.

- Gawlas S., O kształt zjednoczonego Królestwa. Niemieckie władztwo terytorialne a geneza społeczno-ustrojowej odrębności Polski, Warszawa 2000, s. 78–79.

- Labuda G., Testament Bolesława Krzywoustego, (w:) Opuscula Casimiro Tymieniecki septuagenario dedicata, Poznań 1959, s. 171–194.

- Labuda G., Zabiegi o utrzymanie jedności państwa polskiego w latach 1138-1146, „Kwartalnik Historyczny” 66, 1959, z. 4, s. 1147–1167,

- Łowmiański H., Początki Polski, t. VI cz. I, Warszawa 1985, s. 134–165,

- Maleczyński K., Testament Bolesława Krzywoustego (recenzja z: G. Labuda, Testament...), „Sobótka” 16, 1961, z. 1, s. 109-110

- Natanson-Leski J., Nowy rzut oka na podziały według statutu Bolesława Krzywoustego, „Czasopismo Prawno-Historyczne”, t. 8, 1956, z. 2, s. 225–226.

- Rymar E., Primogenitura zasadą regulującą następstwo w pryncypat w ustawie sukcesyjnej Bolesława Krzywoustego, cz. I „Sobótka” 48, 1993, z. I, s. 1–15, cz. II „Sobótka” 49, 1944, z. 1–2, s. 1–18,

- Sosnowska A., Tytulatura pierwszej generacji książąt dzielnicowych z dynastii Piastów (1138-1202), „Historia” 5, 1997, nr 1, s. 7-28.

- Spors J., Podział dzielnicowy Polski według statutu Bolesława Krzywoustego ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem dzielnicy seniorackiej, Słupsk 1978,

- Teterycz A., Rządy księcia Henryka, syna Bolesława Krzywoustego w ziemi Sandomierskiej, (w:) Mazowsze, Pomorze, Prusy. Gdańskie Studia Historyczne z Dziejów Średniowiecza t. 7, red. B. Śliwiński, Gdańsk 2000, s. 245-269

- Wojciechowski T., Szkice historyczne jedenastego wieku, „Kwartalnik Historyczny” 31, 1917, s. 351 i następna.,