Henri Dupuy de Lôme

Stanislas Charles Henri Dupuy de Lôme (French pronunciation: [stanislɑ ʃaʁl ɑ̃ʁi dypɥij d(ə) lom]; 15 October 1816 – 1 February 1885) was a French naval architect. He was the son of a naval officer and was born in Ploemeur near Lorient, Brittany, in western France. He was educated at the École Polytechnique and ENSTA. He was particularly active during the 1840–1870 period.

Henri Dupuy de Lôme | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 October 1816 |

| Died | 1 February 1885 (aged 68) Paris |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Naval architect |

After finishing his professional education, he went to England about 1842, and made a thorough study of iron shipbuilding and steam navigation. He wrote a report, subsequently published under the title of Mémoire sur la construction des bâtiments en fer in 1844.[1]

The first steam battleship

After his return from England, Dupuy de Lôme started work at the arsenal in Toulon. At the time the only armed steamships in the French Navy were propelled by paddle-wheels, and there was great opposition to the introduction of steam power into line-of-battle ships. The paddle-wheel was seen to be unsuited to such large fighting vessels, and there was no confidence in the screw; while the great majority of naval officers in France, as well as in England, were averse to any decrease in sail spread.

Dupuy de Lôme had carefully studied the details of the Great Britain, which he had seen being built at Bristol, and was convinced that full steam power should be used on line-of-battle ships. He held fast to this idea; as early as 1845 he addressed a report to the Minister of Marine suggesting the construction of a screw-driven frigate, to be built with an iron hull, and protected by a belt of armour formed by several thicknesses of iron plating. This report alone would justify his claim to be considered the leading naval architect of that time; such a ship was not built for several years, but the idea of the "classic" iron battleship was clearly stated in this report.

.jpg.webp)

Dupuy de Lôme did not stand alone in the feeling that radical changes in the construction and propulsion of ships were imminent. His colleagues in the Génie Maritime (naval engineering) were impressed with the same idea: and in England, about this date, the earliest screw liners — converted "block ships" — were ordered. This action on the British part decided the French also to begin the conversion of their sailing line-of-battle ships into vessels with auxiliary steam power.

Dupuy de Lôme continued work on the idea, and was rewarded in 1847 with the ordering of Le Napoléon, which would become the first steam-powered battleship as well as the first screw battleship ever built. She was 77.8 m (240 ft) in length, 17 m (55 ft) in breadth, and of 5,000 tons displacement, with two gun decks. She was launched in 1850, tried in 1852, and attained a speed of nearly 14 knots (26 km/h). During the Crimean War her performance attracted great attention, and soon there were plans to introduce steam power to fleets around the world.

The first ironclad battleship

.jpg.webp)

Along with the introduction of steam-power, the use of iron armour was leading to another revolution in design at about the same time. Dupuy de Lôme applied his talents to this field as well, by showing the practicability of armouring the sides of a wooden-built ship. In 1857 he was appointed to the highest office in the Constructive Corps—Directeur du Matériel—and his design for the earliest seagoing ironclad, La Gloire, was approved in the same year. La Gloire was built fairly quickly, and was followed by a construction program that delivered a total of five such ships by 1863.

Among these new ironclads were the only two-decked broadside ironclad battleships ever built, also designed by Dupuy de Lôme - Magenta and Solferino. These ships were also the first to be equipped with a spur ram.

In the design of La Gloire, Dupuy de Lôme followed the principle of utilising known forms and dimensions for existing successful designs, and only changing what was absolutely necessary. The La Gloire nearly reproduced Napoléon so far as under-water shape was concerned, but with one gun deck instead of two, and a completely protected battery. As long as he retained office, Dupuy de Lôme consistently adhered to this principle; but at the same time he showed himself ready to consider how best to meet the constantly growing demands for thicker armour, heavier guns, and higher speeds. It is important to note, however, especially during his early enthusiasm for ironclads, that only a small proportion of the ships added to the French Navy during his time in office were built of anything but wood.

Distinctions were showered upon him. He received the cross of the Legion of Honor in 1845, was made a commander in 1858, and grand officer in December 1863. In 1860 he was made a Councilor of State, and represented the French Admiralty in Parliament; in 1861, he was appointed "inspecteur général du matériel de la Marine" (general inspector for Navy equipment). In 1866 he was elected a member of the Academy of Sciences. At the beginning of the Franco-German War he was appointed a member of the committee of defence.[2] From 1869 to 1875 he was a Deputy, and in 1877 he was elected a Senator for life. He was a member of the Academy of Sciences and of other distinguished scientific bodies.[2]

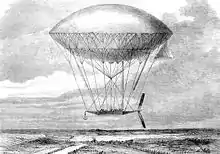

Navigable balloons

Henri Dupuy de Lôme Airship, 1872

Henri Dupuy de Lôme Airship, 1872 The navigable balloon developed by Dupuy de Lome in 1872

The navigable balloon developed by Dupuy de Lome in 1872 The navigable balloon February 2, 1872

The navigable balloon February 2, 1872

In 1870 Dupuy de Lôme devoted a large amount of time to perfecting a practical navigable balloon, and the French Government gave him great assistance in carrying out the experiments. For carrying out the project, he was given a credit of 40,000 francs; but the balloon was not ready until a few days before the capitulation. These experiments led to the development of one of the first navigable balloons, named the Dupuy de Lôme(fr).

The Dupuy de Lôme airship was 36 meters in length, 14.84 meters in diameter, 29 meters tall, and had a total volume of 3,454 cubic meters. It was powered by a crank, which was operated by 4 or 8 men and which could provide a speed of between 9 and 11 km/h.[3] The basket under the balloon could carry 14 people.[4]

In 1875, he was busy over a scheme for embarking a railway train at Calais, and exhibited plans of the improved harbour and models of the "bateaux porte-trains" to the Academy of Sciences in July.[2]

Electrical submarine

Towards the end of his life, Dupuy de Lôme worked on a project for an electrical submarine, largely inspired from the experimental results of the submarine Plongeur. Upon his death, the project was taken over by his friend Gustave Zédé, leading to the launch of one of the first electrical submarines in the world, the Gymnote.

Legacy

Dupuy de Lôme was instrumental in helping the French Navy take the initiative in several of the technological advances of the 19th century, consolidating the position of the French Navy as the second in the world at that time. These innovations relied on a strong industrial base, second only to Britain, and considerably ahead of the United States or Prussia. According to a British obituary, "it may be questioned whether any constructor has ever rendered greater services to the navy of any country...". He died at Paris on 1 February 1885.

Several warships have been named after Dupuy de Lôme:

- The armoured cruiser Dupuy de Lôme, launched in Brest in 1887, was capable of 23 knots (43 km/h), and designed to raid on enemy commerce ships during extended forays afloat, following the "Jeune École" doctrine.

- The submarine Dupuy de Lôme, launched in 1915, and the lead ship of her class.

- Dupuy de Lôme, launched March 27, 2004, and built in the Netherlands for the French Navy, is an intelligence vessel, designed to gather Comint (Communication intelligence) and Elint (Electronic intelligence). She will replace Bougainville from April 2006.

See also

Notes

- Dupuy de Lôme, Mémoire sur la construction des bâtiments en fer [Memoir on the construction of iron ships] (Paris, France: Arthur Bertrand, 1844).

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dupuy de Lôme, Stanislas Charles Henri Laurent". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 691.

- Dupuy de Lôme, Note sur l'Aérostat à Hélice, Construit pour le Compte de l'État [Note on a propeller-driven balloon, constructed on behalf of the French state] (Paris, France: Gauthier-Villars, 1872). The balloon's dimensions appear on pages 9–10. On pages 14–15, Dupuy de Lôme explains that the propeller (hélice) is driven by a hand-operated crank (manivelle), which in turn is operated by a crew of either 4 or 8 men: "L'arbre de l'hélice [porte] … à son extrémité avant la manivelle par laquelle le treuil moteur lui transmet son travail." (The propeller shaft [is connected to] … at its front end the crank by which the hoist motor transmits its power to it [i.e., to the propeller].) "Je dirai enfin que ce treuil à bras, composé tout simplement d'un arbre en fer coudé, … , a ses coudes et ses manivelles placés de façon que le treuil étant manœuvré par quatre ou par huit hommes, … ." (Finally I will say that this hand-powered hoist, [which is] composed quite simply of an iron shaft [bent into a series] of right angles, … , has its bends and its cranks placed so that the hoist being operated by four or by eight men, … .)

- Tissandier, Gaston, Les Ballons dirigeables: Expériences de M. Henri Giffard en 1852 et en 1855 et de M. Dupuy de Lôme en 1872 [Steerable balloons: Experiments of Mr. Henri Giffard in 1852 and in 1855, and of Mr. Dupuy de Lôme in 1872] (Paris, France: E. Dentu, 1872), p. 19 : "L'ascension a été exécutée le 2 février 1872, à 11 heures du matin. L'aérostat était gonflé au fort de Vincennes. MM. Depuy de Lôme, Zedé, Yon, Dartois et dix autres personnes, en y comptant les hommes de manœuvre, prennent place dans la nacelle." (The ascent was undertaken on the 2nd of February 1872 at 11 in the morning. The balloon was inflated at the fort at Vincennes. Messrs. Depuy de Lôme, Zedé, Yon, Dartois and ten other people, which includes the crew, seated themselves in the basket.)

References

- Scientific American Supplement, No. 481, 21 March 1885 (Public Domain)