Dupuytren's contracture

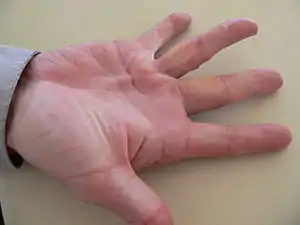

Dupuytren's contracture (also called Dupuytren's disease, Morbus Dupuytren, Viking disease, palmar fibromatosis and Celtic hand) is a condition in which one or more fingers become permanently bent in a flexed position.[2] It is named after Guillaume Dupuytren, who first described the underlying mechanism of action, followed by the first successful operation in 1831 and publication of the results in The Lancet in 1834.[6] It usually begins as small, hard nodules just under the skin of the palm,[2] then worsens over time until the fingers can no longer be fully straightened. While typically not painful, some aching or itching may be present.[2] The ring finger followed by the little and middle fingers are most commonly affected.[2] It can affect one or both hands.[7] The condition can interfere with activities such as preparing food, writing, putting the hand in a tight pocket, putting on gloves, or shaking hands.[2]

| Dupuytren's contracture | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dupuytren's disease, Morbus Dupuytren, palmar fibromatosis, Viking disease, and Celtic hand,[1] contraction of palmar fascia, palmar fascial fibromatosis, palmar fibromas[2] |

| |

| Dupuytren's contracture of the ring finger | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | One or more fingers permanently bent in a flexed position, hard nodule just under the skin of the palm[2] |

| Complications | Trouble preparing food or writing[2] |

| Usual onset | Gradual onset in males over 50[2] |

| Causes | Unknown[4] |

| Risk factors | Family history, alcoholism, smoking, thyroid problems, liver disease, diabetes, epilepsy[2][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[4] |

| Treatment | Steroid injections, clostridial collagenase injections, surgery[4][5] |

| Frequency | ~5% (US)[2] |

The cause is unknown but might have a genetic component.[4] Risk factors include family history, alcoholism, smoking, thyroid problems, liver disease, diabetes, previous hand trauma, and epilepsy.[2][4] The underlying mechanism involves the formation of abnormal connective tissue within the palmar fascia.[2] Diagnosis is usually based on a physical exam.[4] Blood tests or imaging studies are not usually necessary.[7]

Initial treatment is typically with a cortisone shot into the affected area, occupational therapy, and physical therapy.[4] Among those who worsen, clostridial collagenase injections or surgery may be tried.[4][5] Radiation therapy may be used to treat this condition.[8] The Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) Faculty of Clinical Oncology concluded that radiotherapy is effective in early stage disease which has progressed within the last 6 to 12 months. The condition may recur despite treatment.[4] If it does return after treatment, it can be treated again with further improvement. It is easier to treat when the amount of finger bending is more mild.[7]

It was once believed that Dupuytren's most often occurs in white males over the age of 50[2] and is rare among Asians and Africans.[6] It sometimes was erroneously called "Viking disease," since it was often recorded among those of Nordic descent.[6] In Norway, about 30% of men over 60 years old have the condition, while in the United States about 5% of people are affected at some point in time.[2] In the United Kingdom, about 20% of people over 65 have some form of the disease.[6]

More recent and wider studies show the highest prevalence in Africa (17 percent), Asia (15 percent).[9]

Signs and symptoms

Typically, Dupuytren's contracture first presents as a thickening or nodule in the palm, which initially can be with or without pain.[10] Later in the disease process, which can be years later,[11] there is painless increasing loss of range of motion of the affected finger(s). The earliest sign of a contracture is a triangular "puckering" of the skin of the palm as it passes over the flexor tendon just before the flexor crease of the finger, at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint.

Generally, the cords or contractures are painless, but, rarely, tenosynovitis can occur and produce pain. The most common finger to be affected is the ring finger; the thumb and index finger are much less often affected.[12] The disease begins in the palm and moves towards the fingers, with the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints affected before the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints.[13] The MCP joints at the base of the finger responds much better to treatment and are usually able to fully extend after treatment. Due to anatomic differences in the ligaments and extensor tendons at the PIP joints, they may have some residual flexion. Proper patient education is necessary to set realistic treatment expectation.

In Dupuytren's contracture, the palmar fascia within the hand becomes abnormally thick, which can cause the fingers to curl and can impair finger function. The main function of the palmar fascia is to increase grip strength; thus, over time, Dupuytren's contracture decreases a person's ability to hold objects and use the hand in many different activities. Dupuytren's contracture can also be experienced as embarrassing in social situations and can affect quality of life[14] People may report pain, aching, and itching with the contractions. Normally, the palmar fascia consists of collagen type I, but in Dupuytren patients, the collagen changes to collagen type III, which is significantly thicker than collagen type I.[15]

Related conditions

People with severe involvement often show lumps on the back of their finger joints (called "Garrod's pads", "knuckle pads", or "dorsal Dupuytren nodules"), and lumps in the arch of the feet (plantar fibromatosis or Ledderhose disease).[16] In severe cases, the area where the palm meets the wrist may develop lumps. It is thought the condition Peyronie's disease is related to Dupuytren's contracture.[17]

In one study those with stage 2 of the disease were found to have a slightly increased risk of mortality, especially from cancer.[18]

Risk factors

Many risk factors have been suggested or identified:

Non-modifiable

- People of Scandinavian or Northern European ancestry;[19] it has been called the "Viking disease",[6] though it is also widespread in some Mediterranean countries, e.g., Spain[20] and Bosnia.[21][22] Dupuytren's is unusual among groups such as Chinese and Africans.[23]

- Men rather than women; men are more likely to develop the condition (80%)[12][19][24]

- People over the age of 50 (5% to 15% of men in that group in the US); the likelihood of getting Dupuytren's disease increases with age[12][23][24]

- People with a family history (60% to 70% of those affected have a genetic predisposition to Dupuytren's contracture)[12][25]

Modifiable

- Smokers, especially those who smoke 25 cigarettes or more a day[23][26]

- Thinner people, i.e., those with a lower-than-average body mass index.[23]

- Manual work[23][27]

- Alcohol consumption[6][26]

In January 2023, a research paper "Dupuytren's disease is a work-related disorder: results of a population-based cohort study" showed the clear link between manual work and the condition. The study was by researchers at the University of Groningen Medical Centre, Netherlands and Oxford University, UK. They found those with jobs that always or usually involved manual work were 1.29 times more likely to develop Dupuytren's disease than those who rarely or never performed it. They identified a linear dose-response relationship with cumulative manual labour over a 30-year period.[27]

Other conditions

- People with a higher-than-average fasting blood glucose level[23]

- People with previous hand injury[12]

- People with Ledderhose disease (plantar fibromatosis)[12]

- People with epilepsy (possibly due to anti-convulsive medication)[28]

- People with diabetes mellitus[6][28]

- People with HIV[6]

- Previous myocardial infarction[23][24]

Diagnosis

Types

According to the American Dupuytren's specialist Dr. Charles Eaton, there may be three types of Dupuytren's disease:[29]

- Type 1: A very aggressive form of the disease found in only 3% of people with Dupuytren's, which can affect men under 50 with a family history of Dupuytren's. It is often associated with other symptoms such as knuckle pads and Ledderhose disease. This type is sometimes known as Dupuytren's diathesis.[30]

- Type 2: The more normal type of Dupuytren's disease, usually found in the palm only, and which generally begins above the age of 50. According to Eaton, this type may be made more severe by other factors such as diabetes or heavy manual labor.[29]

- Type 3: A mild form of Dupuytren's which is common among diabetics or which may also be caused by certain medications, such as the anti-convulsants taken by people with epilepsy. This type does not lead to full contracture of the fingers, and is probably not inherited.[29]

Treatment

Treatment is indicated when the so-called table-top test is positive. With this test, the person places their hand on a table. If the hand lies completely flat on the table, the test is considered negative. If the hand cannot be placed completely flat on the table, leaving a space between the table and a part of the hand as big as the diameter of a ballpoint pen, the test is considered positive and surgery or other treatment may be indicated. Additionally, finger joints may become fixed and rigid. There are several types of treatment, with some hands needing repeated treatment.

The main categories listed by the International Dupuytren Society in order of stage of disease are radiation therapy, needle aponeurotomy (NA), collagenase injection, and hand surgery. As of 2016 the evidence on the efficacy of radiation therapy was considered inadequate in quantity and quality, and difficult to interpret because of uncertainty about the natural history of Dupuytren's disease.[31]

Needle aponeurotomy is most effective for Stages I and II, covering 6–90 degrees of deformation of the finger. However, it is also used at other stages. Collagenase injection is likewise most effective for Stages I and II. However, it is also used at other stages.

Hand surgery is effective at stage I to stage IV.[32]

Surgery

On 12 June 1831, Dupuytren performed a surgical procedure on a person with contracture of the 4th and 5th digits who had been previously told by other surgeons that the only remedy was cutting the flexor tendons. He described the condition and the operation in The Lancet in 1834[33] after presenting it in 1833, and posthumously in 1836 in a French publication by Hôtel-Dieu de Paris.[34] The procedure he described was a minimally invasive needle procedure.

Because of high recurrence rates, new surgical techniques were introduced, such as fasciectomy and then dermofasciectomy. Most of the diseased tissue is removed with these procedures.Recurrence rates are low. For some individuals, the partial insertion of "K-wires" into either the DIP or PIP joint of the affected digit for a period of a least 21 days to fuse the joint is the only way to halt the disease's progress. After removal of the wires, the joint is fixed into flexion, which is considered preferable to fusion at extension.

In extreme cases, amputation of fingers may be needed for severe or recurrent cases or after surgical complications.[35]

Limited fasciectomy

Limited/selective fasciectomy removes the pathological tissue, and is a common approach.[36][37] Low-quality evidence suggests that fasciectomy may be more effective for people with advanced Dupuytren's contractures.[38]

During the procedure, the person is under regional or general anesthesia. A surgical tourniquet prevents blood flow to the limb.[39] The skin is often opened with a zig-zag incision but straight incisions with or without Z-plasty are also described and may reduce damage to neurovascular bundles.[40] All diseased cords and fascia are excised.[36][37][39] The excision has to be very precise to spare the neurovascular bundles.[39] Because not all the diseased tissue is visible macroscopically, complete excision is uncertain.[37]

A 20-year review of surgical complications associated with fasciectomy showed that major complications occurred in 15.7% of cases, including digital nerve injury (3.4%), digital artery injury (2%), infection (2.4%), hematoma (2.1%), and complex regional pain syndrome (5.5%), in addition to minor complications including painful flare reactions in 9.9% of cases and wound healing complications in 22.9% of cases.[41] After the tissue is removed the incision is closed. In the case of a shortage of skin, the transverse part of the zig-zag incision is left open. Stitches are removed 10 days after surgery.[39]

After surgery, the hand is wrapped in a light compressive bandage for one week. Flexion and extension of the fingers can start as soon as the anaesthesia has resolved. It is common to experience tingling within the first week after surgery.[38] Hand therapy is often recommended.[39] Approximately 6 weeks after surgery the patient is able completely to use the hand.[42]

The average recurrence rate is 39% after a fasciectomy after a median interval of about 4 years.[43]

Wide-awake fasciectomy

Limited/selective fasciectomy under local anesthesia (LA) with epinephrine but no tourniquet is possible. In 2005, Denkler described the technique.[44][45]

Dermofasciectomy

Dermofasciectomy is a surgical procedure that may be used when:

- The skin is clinically involved (pits, tethering, deficiency, etc.)

- The risk of recurrence is high and the skin appears uninvolved (subclinical skin involvement occurs in ~50% of cases[46])

- Recurrent disease.[37] Similar to a limited fasciectomy, the dermofasciectomy removes diseased cords, fascia, and the overlying skin.[47]

Typically, the excised skin is replaced with a skin graft, usually full thickness,[37] consisting of the epidermis and the entire dermis. In most cases the graft is taken from the antecubital fossa (the crease of skin at the elbow joint) or the inner side of the upper arm.[47][48] This place is chosen because the skin color best matches the palm's skin color. The skin on the inner side of the upper arm is thin and has enough skin to supply a full-thickness graft. The donor site can be closed with a direct suture.[47]

The graft is sutured to the skin surrounding the wound. For one week the hand is protected with a dressing. The hand and arm are elevated with a sling. The dressing is then removed and careful mobilization can be started, gradually increasing in intensity.[47] After this procedure the risk of recurrence is minimised,[37][47][48] but Dupuytren's can recur in the skin graft[49] and complications from surgery may occur.[50]

Segmental fasciectomy with/without cellulose

Segmental fasciectomy involves excising part(s) of the contracted cord so that it disappears or no longer contracts the finger. It is less invasive than the limited fasciectomy, because not all the diseased tissue is excised and the skin incisions are smaller.[51]

The person is placed under regional anesthesia and a surgical tourniquet is used. The skin is opened with small curved incisions over the diseased tissue. If necessary, incisions are made in the fingers.[51] Pieces of cord and fascia of approximately one centimeter are excised. The cords are placed under maximum tension while they are cut. A scalpel is used to separate the tissues.[51] The surgeon keeps removing small parts until the finger can fully extend.[51][52] The person is encouraged to start moving his or her hand the day after surgery. They wear an extension splint for two to three weeks, except during physical therapy.[51]

The same procedure is used in the segmental fasciectomy with cellulose implant. After the excision and a careful hemostasis, the cellulose implant is placed in a single layer in between the remaining parts of the cord.[52]

After surgery people wear a light pressure dressing for four days, followed by an extension splint. The splint is worn continuously during nighttime for eight weeks. During the first weeks after surgery the splint may be worn during daytime.[52]

Less invasive treatments

Studies have been conducted for percutaneous release, extensive percutaneous aponeurotomy with lipografting and collagenase. These treatments show promise.[53][54][55][56]

Percutaneous needle fasciotomy

Needle aponeurotomy is a minimally-invasive technique where the cords are weakened through the insertion and manipulation of a small needle. The cord is sectioned at as many levels as possible in the palm and fingers, depending on the location and extent of the disease, using a 25-gauge needle mounted on a 10 ml syringe.[53] Once weakened, the offending cords can be snapped by putting tension on the finger(s) and pulling the finger(s) straight. After the treatment a small dressing is applied for 24 hours, after which people are able to use their hands normally. No splints or physiotherapy are given.[53]

The advantage of needle aponeurotomy is the minimal intervention without incision (done in the office under local anesthesia) and the very rapid return to normal activities without need for rehabilitation, but the nodules may resume growing.[57] A study reported postoperative gain is greater at the MCP-joint level than at the level of the IP-joint and found a reoperation rate of 24%; complications are scarce.[58] Needle aponeurotomy may be performed on fingers that are severely bent (stage IV), and not just in early stages. A 2003 study showed 85% recurrence rate after 5 years.[59]

A comprehensive review of the results of needle aponeurotomy in 1,013 fingers was performed by Gary M. Pess, MD, Rebecca Pess, DPT, and Rachel Pess, PsyD, and published in the Journal of Hand Surgery April 2012. Minimal follow-up was 3 years. Metacarpophalangeal joint (MP) contractures were corrected at an average of 99% and proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) contractures at an average of 89% immediately post procedure. At final follow-up, 72% of the correction was maintained for MP joints and 31% for PIP joints. The difference between the final corrections for MP versus PIP joints was statistically significant. When a comparison was performed between people aged 55 years and older versus under 55 years, there was a statistically significant difference at both MP and PIP joints, with greater correction maintained in the older group.

Gender differences were not statistically significant. Needle aponeurotomy provided successful correction to 5° or less contracture immediately post procedure in 98% (791) of MP joints and 67% (350) of PIP joints. There was recurrence of 20° or less over the original post-procedure corrected level in 80% (646) of MP joints and 35% (183) of PIP joints. Complications were rare except for skin tears, which occurred in 3.4% (34) of digits. This study showed that NA is a safe procedure that can be performed in an outpatient setting. The complication rate was low, but recurrences were frequent in younger people and for PIP contractures.[60]

Extensive percutaneous aponeurotomy and lipografting

A technique introduced in 2011 is extensive percutaneous aponeurotomy with lipografting.[54] This procedure also uses a needle to cut the cords. The difference with the percutaneous needle fasciotomy is that the cord is cut at many places. The cord is also separated from the skin to make place for the lipograft that is taken from the abdomen or ipsilateral flank.[54] This technique shortens the recovery time. The fat graft results in supple skin.[54]

Before the aponeurotomy, a liposuction is done to the abdomen and ipsilateral flank to collect the lipograft.[54] The treatment can be performed under regional or general anesthesia. The digits are placed under maximal extension tension using a firm lead hand retractor. The surgeon makes multiple palmar puncture wounds with small nicks. The tension on the cords is crucial, because tight constricting bands are most susceptible to be cut and torn by the small nicks, whereas the relatively loose neurovascular structures are spared. After the cord is completely cut and separated from the skin the lipograft is injected under the skin. A total of about 5 to 10 ml is injected per ray.[54]

After the treatment the person wears an extension splint for 5 to 7 days. Thereafter the person returns to normal activities and is advised to use a night splint for up to 20 weeks.[54]

Collagenase

_for_Dupuytrens.jpg.webp)

The cords are weakened through the injection of small amounts of the enzyme collagenase, which breaks peptide bonds in collagen.[55][61][62][63][56]

Clostridial collagenase injections have been found to be more effective than placebo.[5]

In February 2010 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved injectable collagenase extracted from Clostridium histolyticum for the treatment of Dupuytren's contracture in adults with a palpable Dupuytren's cord. (Three years later, it was approved as well for the treatment of the sometimes related Peyronie's disease.)[64][11] In 2011 its use for the treatment of Dupuytren's contracture was approved as well by the European Medicines Agency, and it received similar approval in Australia in 2013.[11] However, the Swedish manufacturer abruptly withdrew distribution of this drug in Europe and the UK in March 2020 for commercial reasons.[65](It now is promoted primarily as a dermatological treatment for cellulite aka "cottage cheese thighs").[66] Collagenase is no longer available on the National Health System except as part of a small clinical trial.[67]

The treatment with collagenase is different for the MCP joint and the PIP joint. In a MCP joint contracture the needle must be placed at the point of maximum bowstringing of the palpable cord.[55] The needle is placed vertically on the bowstring. The collagenase is distributed across three injection points.[55] For the PIP joint the needle must be placed not more than 4 mm distal to palmar digital crease at 2–3 mm depth.[55] The injection for PIP consists of one injection filled with 0.58 mg CCH 0.20 ml.[56] The needle must be placed horizontal to the cord and also uses a 3-point distribution.[55] After the injection the person's hand is wrapped in bulky gauze dressing and must be elevated for the rest of the day. After 24 hours the person returns for passive digital extension to rupture the cord. Moderate pressure for 10–20 seconds ruptures the cord.[55] After the treatment with collagenase the person should use a night splint and perform digital flexion/extension exercises several times per day for 4 months.[55]

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy has been used mostly for early-stage disease, but is unproven.[8] Evidence to support its use as of 2017, however, was scarce —efforts to gather evidence are complicated due to a poor understanding of how the condition develops over time.[8][31] It has only been looked at in early disease.[8] The Royal College of Radiologists concluded that radiotherapy is effective in early stage disease which has progressed within the last 6 to 12 months.[68]

Alternative medicine

Several alternate therapies such as vitamin E treatment have been studied, though without control groups. Most doctors do not value those treatments.[69] None of these treatments stops or cures the condition permanently. A 1949 study of vitamin E therapy found that "In twelve of the thirteen patients there was no evidence whatever of any alteration. ... The treatment has been abandoned."[70][71]

Laser treatment (using red and infrared at low power) was informally discussed in 2013 at an International Dupuytren Society forum,[72] as of which time little or no formal evaluation of the techniques had been completed.

Postoperative care

Postoperative care involves hand therapy and splinting. Hand therapy is prescribed to optimize post-surgical function and to prevent joint stiffness. The extent of hand therapy is depending on the patient and the corrective procedure.[73]

Besides hand therapy, many surgeons advise the use of static or dynamic splints after surgery to maintain finger mobility. The splint is used to provide prolonged stretch to the healing tissues and prevent flexion contractures. Although splinting is a widely used post-operative intervention, evidence of its effectiveness is limited,[74] leading to variation in splinting approaches. Most surgeons use clinical experience to decide whether to splint.[75] Cited advantages include maintenance of finger extension and prevention of new flexion contractures. Cited disadvantages include joint stiffness, prolonged pain, discomfort,[75] subsequently reduced function and edema.

A third approach emphasizes early self-exercise and stretching.[45]

Prognosis

Dupuytren's disease has a high recurrence rate, especially when a person has so-called Dupuytren's diathesis. The term diathesis relates to certain features of Dupuytren's disease, and indicates an aggressive course of disease.[30]

The presence of all new Dupuytren's diathesis factors increases the risk of recurrent Dupuytren's disease by 71%, compared with a baseline risk of 23% in people lacking the factors.[30] In another study the prognostic value of diathesis was evaluated. It was concluded that presence of diathesis can predict recurrence and extension.[76] A scoring system was made to evaluate the risk of recurrence and extension, based on the following values: bilateral hand involvement, little-finger surgery, early onset of disease, plantar fibrosis, knuckle pads, and radial side involvement.[76]

Minimally invasive therapies may precede higher recurrence rates. Recurrence lacks a consensus definition. Furthermore, different standards and measurements follow from the various definitions.

Notable cases

- Chelsea Handler (born 1975), American comedian, actress and writer[77][78]

- Tim Herron (born 1970), American golfer[79]

- Prince Joachim of Denmark (born 1969)[80]

- Joanne Harris (born 1964), British author[81]

- Jonathan Agnew (born 1960), English cricketer[82]

- John Elway (born 1960), American football player[83]

- Nanci Griffith (1953–2021), American singer, guitarist, and songwriter[84][85]

- Bill Murray (born 1950), American actor and comedian[86]

- Bill Nighy (born 1949), English actor[87]

- Mitt Romney (born 1947), American politician[77]

- Misha Dichter (born 1945), American pianist[88]

- José Feliciano (born 1945), Puerto Rican musician, singer and composer[89]

- Bill Frindall (1939–2009), English cricket player and statistician, who had a finger amputated.[90]

- David McCallum (1933–2023), Scottish/British actor and musician[91]

- Paul Newman (1925–2008), American actor and film director[77]

- Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013), Prime Minister of the United Kingdom[92]

- Ronald Reagan (1911–2004), American President and actor[92]

- Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009), American visual artist[77]

- Frank Sinatra (1915–1998), American singer, actor, and producer[93]

- Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), Irish novelist, poet and playwright[77]

- Max Planck (1858–1947), German theoretical physicist and Nobel Prize laureate[77]

References

- Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York [u.a.]: McGraw-Hill. 2003. p. 989. ISBN 978-0-07-138076-8.

- "Dupuytren contracture". Genetics Home Reference. US: National Library of Health, National Institutes of Health. September 2016. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- "Dupuytren's contracture". Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Dupuytren's Contracture". National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2005. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Brazzelli, M; Cruickshank, M; Tassie, E; McNamee, P; et al. (October 2015). "Collagenase clostridium histolyticum for the treatment of Dupuytren's contracture: systematic review and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment. 19 (90): 1–202. doi:10.3310/hta19900. PMC 4781188. PMID 26524616.

- Hart, M. G.; Hooper, G. (2005). "Clinical associations of Dupuytren's disease". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 81 (957): 425–28. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.027425. PMC 1743313. PMID 15998816.

- The American Society for Surgery of the Hand (2021). "Dupuytren's Contracture". HandCare: The Upper Extremity Expert. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Kadhum, M; Smock, E; Khan, A; Fleming, A (1 March 2017). "Radiotherapy in Dupuytren's disease: a systematic review of the evidence". The Journal of Hand Surgery, European Volume. 42 (7): 689–92. doi:10.1177/1753193417695996. PMID 28490266. S2CID 206785758.

On balance, radiotherapy should be considered an unproven treatment for early Dupuytren's disease due to a scarce evidence base and unknown long-term adverse effects.

- Ruettermann M, Hermann RM, Khatib-Chahidi K, Werker PM (November 2021). "Dupuytren's Disease-Etiology and Treatment". Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 118 (46): 781–788. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0325. PMC 8864671. PMID 34702442.

- "Dupuytren's contracture – Symptoms". National Health Service (England). 2017-10-19. Archived from the original on 2016-04-08. Page last reviewed: 29/05/2015

- Giorgio Pajardi; Marie A. Badalamente; Lawrence C. Hurst (2018). Collagenase in Dupuytren Disease. Springer. ISBN 9783319658223. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- Lanting, Rosanne; Van Den Heuvel, Edwin R.; Westerink, Bram; Werker, Paul M. N. (2013). "Prevalence of Dupuytren Disease in the Netherlands" (PDF). Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 132 (2): 394–403. doi:10.1097/prs.0b013e3182958a33. PMID 23897337. S2CID 46900744.

- Nunn, Adam C.; Schreuder, Fred B. (2014). "Dupuytren's Contracture: Emerging Insight into a Viking Disease". Hand Surgery. 19 (3): 481–90. doi:10.1142/S0218810414300058. PMID 25288296.

- Turesson, Christina; Kvist, Joanna; Krevers, Barbro (2020). "Experiences of men living with Dupuytren's disease—Consequences of the disease for hand function and daily activities". Journal of Hand Therapy. 33 (3): 386–393. doi:10.1016/j.jht.2019.04.004. ISSN 0894-1130. PMID 31477329. S2CID 201804901.

- Al-Qattan, Mohammad (November 1, 2006). "Factors in the Pathogenesis of Dupuytren's Contracture". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 31 (9): 1527–1534. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.08.012. PMID 17095386 – via Elsevier.

- Reference, Genetics Home. "Dupuytren contracture". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Carrieri, MP; Serraino, D; Palmiotto, F; Nucci, G; Sasso, F (1998). "A case-control study on risk factors for Peyronie's disease". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 51 (6): 511–5. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00015-8. PMID 9636000.

- Gudmundsson, Kristján G.; Arngrı́Msson, Reynir; Sigfússon, Nikulás; Jónsson, Thorbjörn (2002). "Increased total mortality and cancer mortality in men with Dupuytren's disease". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 55 (1): 5–10. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00413-9. PMID 11781116.

- "Your Orthopaedic Connection: Dupuytren's Contracture". Archived from the original on 2007-03-13.

- Guitian, A. Quintana (1988). "Quelques aspects épidémiologiques de la maladie de Dupuytren" [Various epidemiologic aspects of Dupuytren's disease]. Annales de Chirurgie de la Main (in Spanish). 7 (3): 256–62. doi:10.1016/S0753-9053(88)80013-9. PMID 3056294.

- Zerajic, Dragan; Finsen, Vilhjalmur (2012). "The Epidemiology of Dupuytren's Disease in Bosnia". Dupuytren's Disease and Related Hyperproliferative Disorders. pp. 123–7. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-22697-7_16. ISBN 978-3-642-22696-0.

- "Age and geographic distribution of Dupuytren's disease (Dupuytren's contracture)". Dupuytren-online.info. 2012-11-21. Archived from the original on 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- Gudmundsson, Kristján G.; Arngrı́Msson, Reynir; Sigfússon, Nikulás; Björnsson, Árni; Jónsson, Thorbjörn (2000). "Epidemiology of Dupuytren's disease". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 53 (3): 291–6. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00145-6. PMID 10760640.

- Mark D. Miller; Jennifer Hart; John M. MacKnight (2019). Essential Orthopaedics E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323567046. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- "Dupuytren's Contracture". Archived from the original on 2016-06-16.

- Burge, Peter; Hoy, Greg; Regan, Padraic; Milne, Ruairidh (1997). "Smoking, Alcohol and the Risk of Dupuytren's Contracture". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 79 (2): 206–10. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.79b2.6990. PMID 9119843.

- van den Berge, Bente A.; Wiberg, Akira; Werker, Paul M. N.; Broekstra, Dieuwke C.; Furniss, Dominic (March 2023). "Dupuytren's disease is a work-related disorder: results of a population-based cohort study". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 80 (3): 137–145. doi:10.1136/oemed-2022-108670. PMC 9985760. PMID 36635095.

- "Etiology of Dupuytren's Disease" Archived 2016-10-12 at the Wayback Machine Living Textbook of Hand Surgery.

- "Three types of Dupuytren disease?". Dupuytren Research Group. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016.

- Hindocha, Sandip; Stanley, John K.; Watson, Stewart; Bayat, Ardeshir (2006). "Dupuytren's Diathesis Revisited: Evaluation of Prognostic Indicators for Risk of Disease Recurrence". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 31 (10): 1626–34. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.09.006. PMID 17145383.

- "Radiation therapy for early Dupuytren's disease: Guidance and guidelines". NICE. December 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-06-28.

- "Progression of Dupuytren's disease". Dupuytren-online.info. 2012-08-18. Archived from the original on 2013-03-22. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- "Clinical Lectures on Surgery". The Lancet. 22 (558): 222–5. 1834. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)77708-8. hdl:2027/uc1.$b426113. PMC 5165315.

- Dupuytren, Guillaume (1836). "Rétraction Permanente des Doigts". Leçons Orales de Clinique Chirurgicale, Faites a l'Hotel-Dieu de Paris. 1: 1–12.

- Townley, W. A.; Baker, R.; Sheppard, N.; Grobbelaar, A. O. (2006). "Dupuytren's contracture unfolded". BMJ. 332 (7538): 397–400. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7538.397. PMC 1370973. PMID 16484265.

- Skoff, H. D. (2004). "The surgical treatment of Dupuytren's contracture: A synthesis of techniques". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 113 (2): 540–4. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000101054.80392.88. PMID 14758215. S2CID 41351257.

- Khashan, Morsi; Smitham, P. J.; Khan, W. S.; Goddard, N. J. (2011). "Dupuytren's Disease: Review of the Current Literature". The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 5: 283–8. doi:10.2174/1874325001105010283. PMC 3149852. PMID 21886694.

- Rodrigues, Jeremy N.; Becker, Giles W.; Ball, Cathy; Zhang, Weiya; Giele, Henk; Hobby, Jonathan; Pratt, Anna L.; Davis, Tim (2015-12-09). "Surgery for Dupuytren's contracture of the fingers" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (12): CD010143. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010143.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6464957. PMID 26648251.

- Van Rijssen, Annet L.; Gerbrandy, Feike S. J.; Linden, Hein Ter; Klip, Helen; Werker, Paul M.N. (2006). "A Comparison of the Direct Outcomes of Percutaneous Needle Fasciotomy and Limited Fasciectomy for Dupuytren's Disease: A 6-Week Follow-Up Study". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 31 (5): 717–25. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.02.021. PMID 16713831.

- Robbins, T. H. (1981). "Dupuytren's contracture: The deferred Z-plasty". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 63 (5): 357–8. PMC 2493820. PMID 7271195.

- Denkler, K (2010). "Surgical complications associated with fasciectomy for Dupuytren's disease: A 20-year review of the English literature". ePlasty. 10: e15. PMC 2828055. PMID 20204055.

- Van Rijssen, A. L.; Werker, P. M. (2009). "Treatment of Dupuytren's contracture; an overview of options". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 153: A129. PMID 19857298.

- Crean, S. M.; Gerber, R. A.; Le Graverand, M. P. H.; Boyd, D. M.; Cappelleri, J. C. (2011). "The efficacy and safety of fasciectomy and fasciotomy for Dupuytren's contracture in European patients: A structured review of published studies". Journal of Hand Surgery. 36 (5): 396–407. doi:10.1177/1753193410397971. PMID 21382860. S2CID 6244809.

- Denkler, K (2005). "Dupuytren's fasciectomies in 60 consecutive digits using lidocaine with epinephrine and no tourniquet". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 115 (3): 802–10. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000152420.64842.b6. PMID 15731682. S2CID 40168308.

- Bismil, Q.; Bismil, M.; Bismil, A.; Neathey, J.; Gadd, J.; Roberts, S.; Brewster, J. (2012). "The development of one-stop wide-awake Dupuytren's fasciectomy service: A retrospective review". JRSM Short Reports. 3 (7): 48. doi:10.1258/shorts.2012.012050. PMC 3422854. PMID 22908029.

- Wade, Ryckie; Igali, Laszlo; Figus, Andrea (9 September 2015). "Skin involvement in Dupuytren's disease" (PDF). Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). 41 (6): 600–608. doi:10.1177/1753193415601353. PMID 26353945. S2CID 44308422.

- Armstrong, J. R.; Hurren, J. S.; Logan, A. M. (2000). "Dermofasciectomy in the management of Dupuytren's disease". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 82 (1): 90–4. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.82b1.9808. PMID 10697321.

- Ullah, A. S.; Dias, J. J.; Bhowal, B. (2009). "Does a 'firebreak' full-thickness skin graft prevent recurrence after surgery for Dupuytren's contracture?: a prospective, randomised trial". Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 91-B (3): 374–8. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.91B3.21054. PMID 19258615. S2CID 45221140.

- Wade, Ryckie George; Igali, Laszlo; Figus, Andrea (August 2016). "Dupuytren Disease Infiltrating a Full-Thickness Skin Graft" (PDF). The Journal of Hand Surgery. 41 (8): e235–e238. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.04.011. PMID 27282210.

- Bainbridge, Christopher; Dahlin, Lars B.; Szczypa, Piotr P.; Cappelleri, Joseph C.; Guérin, Daniel; Gerber, Robert A. (2012). "Current trends in the surgical management of Dupuytren's disease in Europe: An analysis of patient charts". European Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 3 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1007/s12570-012-0092-z. PMC 3338000. PMID 22611457.

- Moermans, J (1991). "Segmental aponeurectomy in Dupuytren's disease". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 16 (3): 243–54. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1028.1469. doi:10.1016/0266-7681(91)90047-R. PMID 1960487. S2CID 45886218.

- Degreef, Ilse; Tejpar, Sabine; De Smet, Luc (2011). "Improved postoperative outcome of segmental fasciectomy in Dupuytren disease by insertion of an absorbable cellulose implant". Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery. 45 (3): 157–64. doi:10.3109/2000656X.2011.558725. PMID 21682613. S2CID 26305500.

- Van Rijssen, Annet L.; Werker, Paul M.N. (2012). "Percutaneous Needle Fasciotomy for Recurrent Dupuytren Disease". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 37 (9): 1820–3. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.05.022. PMID 22763055.

- Hovius, Steven E. R.; Kan, Hester J.; Smit, Xander; Selles, Ruud W.; Cardoso, Eufimiano; Khouri, Roger K. (2011). "Extensive Percutaneous Aponeurotomy and Lipografting: A New Treatment for Dupuytren Disease". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 128 (1): 221–8. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821741ba. PMID 21701337. S2CID 19339536.

- Bayat, Ardeshir; Thomas (2010). "The emerging role of Clostridium histolyticum collagenase in the treatment of Dupuytren disease". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 6: 557–72. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S8591. PMC 2988615. PMID 21127696.

- Hurst, Lawrence C.; Badalamente, Marie A.; Hentz, Vincent R.; Hotchkiss, Robert N.; Kaplan, F. Thomas D.; Meals, Roy A.; Smith, Theodore M.; Rodzvilla, John (2009). "Injectable Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum for Dupuytren's Contracture". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (10): 968–79. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810866. PMID 19726771. S2CID 23771087.

- Lellouche, Henri (2008). "Maladie de Dupuytren: La chirurgie n'est plus obligatoire" [Dupuytren's contracture: surgery is no longer necessary]. La Presse Médicale (in French). 37 (12): 1779–81. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2008.07.012. PMID 18922672.

- Foucher, G (2003). "Percutaneous needle aponeurotomy: Complications and results". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 28 (5): 427–31. doi:10.1016/S0266-7681(03)00013-5. PMID 12954251. S2CID 11181513.

- Van Rijssen, Annet L.; Ter Linden, Hein; Werker, Paul M. N. (2012). "Five-Year Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial on Treatment in Dupuytrenʼs Disease". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 129 (2): 469–77. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aea95. PMID 21987045. S2CID 24454361.

- Pess, Gary M.; Pess, Rebecca M.; Pess, Rachel A. (2012). "Results of Needle Aponeurotomy for Dupuytren Contracture in over 1,000 Fingers". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 37 (4): 651–6. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.029. PMID 22464232.

- Badalamente, Marie A.; Hurst, Lawrence C. (2007). "Efficacy and Safety of Injectable Mixed Collagenase Subtypes in the Treatment of Dupuytren's Contracture". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 32 (6): 767–74. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.04.002. PMID 17606053.

- Badalamente, Marie A.; Hurst, Lawrence C. (2000). "Enzyme injection as nonsurgical treatment of Dupuytren's disease". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 25 (4): 629–36. doi:10.1053/jhsu.2000.6918. PMID 10913202. S2CID 24029657.

- Badalamente, Marie A.; Hurst, Lawrence C.; Hentz, Vincent R. (2002). "Collagen as a clinical target: Nonoperative treatment of Dupuytren's disease". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 27 (5): 788–98. doi:10.1053/jhsu.2002.35299. PMID 12239666.

- "FDA Approves Xiaflex for Debilitating Hand Condition". Fda.gov. 2010-02-02. Archived from the original on 2012-11-26. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- "Xiapex | European Medicines Agency". 17 September 2018.

- "Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum Injection: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov.

- "Dupuytren's Interventions: Surgery vs Collagenase - Trials and Statistics, University of York".

- "Re: Dupuytren's disease". 7 August 2021. pp. n1308.

- Proposed Natural Treatments for Dupuytren's Contracture, EBSCO Complementary and Alternative Medicine Review Board, 2 February 2011 Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Date February 2011.

- King, Raymond A (August 1949). "Vitamin E therapy in Dupuytren's contracture - Examination of the Claim that Vitamin Therapy is Successful" (PDF). The Bone & Joint Journal. 31B (3): 443.

- Therapies for Dupuytren's contracture and Ledderhose disease with possibly less benefit, International Dupuytren Society, 19 January 2011 Archived 14 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cold Laser Treatment Archived 2013-11-09 at the Wayback Machine at International Dupuytren Society online forum. Accessed: 28 August 2012.

- Turesson, Christina (2018-08-01). "The Role of Hand Therapy in Dupuytren Disease". Hand Clinics. 34 (3): 395–401. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2018.03.008. ISSN 0749-0712. PMID 30012299. S2CID 51651115.

- Jerosch-Herold, Christina; Shepstone, Lee; Chojnowski, Adrian J.; Larson, Debbie (2008). "Splinting after contracture release for Dupuytren's contracture (SCoRD): Protocol of a pragmatic, multi-centre, randomized controlled trial". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 9: 62. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-9-62. PMC 2386788. PMID 18447898.

- Larson, Debbie; Jerosch-Herold, Christina (2008). "Clinical effectiveness of post-operative splinting after surgical release of Dupuytren's contracture: A systematic review". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 9: 104. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-9-104. PMC 2518149. PMID 18644117.

- Abe, Y. (2004). "An objective method to evaluate the risk of recurrence and extension of Dupuytren's disease". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 29 (5): 427–30. doi:10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.06.004. PMID 15336743. S2CID 27542382.

- "Local MD Will Speak on Crippling Hand Disease Which Affects Many Seniors," Sun-Sentinel, July 15, 2014

- Dana Leigh Smith: Hand Trouble? It Might Be THIS, womenshealthmag.com, May 8, 2013

- Helen Ross (November 6, 2018). "Herron dealing with early stages of Dupuytren's contracture". PGATour.

- "Joachim opereret for krumme fingre". HER&NU. March 17, 2013. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013.

- New Treatment Straightens Bent Fingers without Surgery, springgroup.org

- Jonathan Agnew: How my Viking ancestry nearly cost me my hands, telegraph.co.uk, 27 July 2017

- Chelsea Howard (August 22, 2019). "Broncos' John Elway opens up about 15-year battle with debilitating hand condition". Sporting News. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- Belcher, David (February 29, 2012). "Politics Sung With a Texas Kick". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021.

- Sweeting, Adam (August 15, 2021). "Nanci Griffith obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021.

- Dupuytren Disease and the Dupuytren Research Group, dupuytrens.org

- Farndale, Nigel (February 8, 2015). "Bill Nighy: 'I'm greedy for beauty'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Pollack, Andrew (March 15, 2010). "Triumph for Drug to Straighten Clenched Fingers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 18, 2010.

- Joe Bosso: José Feliciano on the Enduring Ecstasies of Guitar Playing, guitarplayer.com, May 8, 2020

- Jonathan Agnew, Aggers' Ashes (London, 2011), page 103

- David McCallum, imdb.com

- Drug Approved to Treat Hand-Crippling Syndrome Archived 2010-04-09 at the Wayback Machine, Delthia Ricks, Chicago Tribune, March 17, 2010.

- Spencer Leigh (2015). Frank Sinatra: An Extraordinary Life. McNidder and Grace Limited. ISBN 9780857160881. Retrieved 2020-01-18.