Duror

Duror (Scottish Gaelic: An Dùrar, meaning hard water), occasionally Duror of Appin, is a small, remote coastal village that sits at the base of Glen Duror, in district of Appin, in the Scottish West Highlands, within the council area of Argyll and Bute in Scotland.[1] Duror is known for the first building of the Telford Parliamentary churches by the Scottish civil engineer, architect and stonemason, Thomas Telford, from 1826, the first in a series of 32, built in Scotland. William Thomson was the architect.[2] Duror is the location of the famous Appin Murder. Although no direct evidence for this connection exists, the murder event and the kidnap of James Annesley, supposedly provided the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson writing the novel Kidnapped.

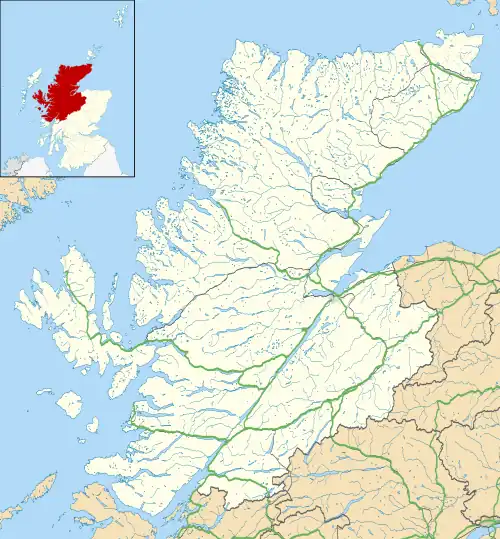

Duror

| |

|---|---|

| |

Duror  Duror Location within the Highland council area | |

| Population | 726 |

| OS grid reference | NM992552 |

| Council area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Appin |

| Postcode district | PA38 |

| Dialling code | 01631 74 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament |

|

| Scottish Parliament | |

History of Duror

Prehistory

Duror is a very ancient settlement, at least 5000 years old, when the Achara stone, described below, was placed close to the shore of Loch Linnhe and was likely a religious meeting place for pagan Iron Age settlers, who worshiped a pantheon of Gods and Goddesses, with religious ceremonies conducted by Druids who spoke a form of a Celtic language.[3] Sea levels were some 14 metres (46 ft) higher, during that time in pre-history, indicating the Achara stone may have been sited next to the seashore. This can be explicitly seen in the Clach Thoull - The Holed Stone, which was considered the mythical entrance to the nether regions under the sea, and where the hole in the stone has been created by sea erosion. During that time, there were many more islands in Cuil Bay.[4] The Ballachulish figure was discovered in November 1880, buried in peat, at Alltshellach in North Ballachulish. The figure is on display in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.[5] Traces of wicker suggest the remains of a wooden shrine. Her identity was unknown, but was possibly an early example of a Celtic nature goddess.[3] One Celtic deity, whose cult originated in Gaul, was the warrior-god Camulus, whose worship spread to the British Isles by the 1st century AD, with religious ceremonies conducted by Druids and who spoke a form of Celtic language.[3]

Mini Ice Age

Around 1300BC, the climate changed dramatically, with temperatures dropping and rainfall levels doubling within 10 years. Evidence indicated this caused the whole population of the Scottish Highlands, to move to the Central Belt, with the tree line dropping from about 750 metres to 500 metres, equivalent to a temperature drop of 1.5°, which was also seen in England as a reduction in elm growth.[6] Gradually the climate became more suitable and settlers returned to the Scottish Highlands, around between 100 and 600AD.

Dál Riata and Viking kingdoms

From the 6th century AD to the 8th century AD, Duror was part of the kingdom of Dál Riata, specifically part of the Loarn mac Eirc, the Kingdom of Lorne, which was one of the four main northerly clans or kindreds of Dál Riata. The Dál Riatas, people who were called the Scoti, who were Irish immigrants, introduced the Gaelic language and Christianity into Scotland, and also gave Scotland its name. At the centre of Dál Riata Christianity was the monastery founded by Saint Columba on Iona, the small island in the Inner Hebrides. Duror has a medieval church, now a ruin located in Kiel, which is dedicated to Saint Columba. It was disused even in the days of James Stewart. It is certainly possible that Saint Columba visited Duror, on the dedication of the church.[7]

During the 9th century and 10th century, Duror, like much of western Scotland, was conquered by the Vikings.[7]

Medieval period

Later during the 14th century and 15th century, the district of Duror was incorporated into lands owned by the Lord of the Isles. This was a part Norse, part Scottish Gaelic speaking principality, ruled by the Clan Macdonalds. Towards the end of the 15th century, the MacDonald Lords lost their power, when in 1493, John MacDonald forfeited his estates and titles to King James IV of Scotland, which was greatly to their disadvantage.[8] Clan Campbell, from their heartland in Loch Awe and Loch Avich, began to expand their territory across mainland Argyll and into the Hebrides islands[8] The expansion of Clan Campbell meant that the Lord of Lorne, whose title derived from their control of the mid-Argyll district of that name, and whose family name was Stewart, who had their family seat at Dunstaffnage Castle, gradually lost control of the jurisdiction of the Appin area. For the next 300 years, the branches of the Clan Campbell's, operating from their stronghold, Barcaldine Castle controlled the land surrounding Appin, an area that the Stewart Lords of Lorn expected to be theirs indefinitely.[9] The Stewarts fought back, John Stewart's son, Dugald Stewart, retreated from Lorn but stubbornly refused to subordinate themselves to their new masters.[9] In the bloody Battle of Stalc,[10][11] fought in Portnacroish, 7 miles southwest of Duror, which is now a graveyard, Colin Campbell organized a massive raid against Dugald and his clan, eventually losing many men, Dugald virtually destroyed the military strength of the MacFarlanes and personally killed Alan MacCoul, his father's murderer. The battle solidified Dugald's claim to Appin and the surrounding area, which was formally granted to him by King James III on 14 April 1470.

At the battle of Battle of Inverlochy in 1645, the third battle at Inverlochy, Daniel Colquhoun was granted land at Duror but most of Appin land was retained by the Clan Stewart of Appin until 1766, when the Appin Estate was sold to Hugh Seton of Touch (Touch House). In the 1760s, the primary school at Duror was established, where 29 scholars, from a wide range of backgrounds were declared in 1777 to have reached a satisfactory level in reading of English and writing.[12]

Improved roads and transport

In 1788, Hugh Seton employed the firm responsible for the Forth and Clyde Canal in project jointly funded by the Forfeited Estates Commission to improve the Water of Duror, which had been long subject to floods. Retaining walls and embankments were constructed at a cost of around £150. They were so robustly built, that they remained in place until they were badly damaged by a freak flood in 1953.[12] Seton also built an arched and stone built bridge that survived the flood and replaced the Wooden bridges that had been rebuilt over a period of 800 years. The bridge was put in place across the Water of Duror about a quarter of a mile downstream from Inshaig.[12] The bridge, now only used by walkers, helped make possible, or so it was reported an excellent line of road, from Shian Ferry to Glencoe Along this road, by the 1780s at a previous undreamed of speed. A local clergyman noted in amazement that it took two-and-a-half days to reach Duror from Edinburgh.[12]

Tourism in the 18th century

The poet Anne Grant, possibly one of the first highlanders, and certainly the first one to write about the Scottish Highlands in English, sighted Duror when sailing up Loch Linnhe from Oban to Fort William in May 1773, declared:

- I never saw a place that had more attractions to me, It was wild without being savage; woody, but not gloomy; and fertile but not flat [13]

Dorothy Wordsworth, who visited Duror in September 1803, with her brother, the poet William Wordsworth, also complemented Duror. Riding north by way of Dalnarat and Keil, the Wordsworth's reached the vicinity of Insaig, where they found themselves, as Dorothy noted in:

- in a retired valley scattered over with many grey huts.. there were hay ground in the middle of this valley and everywhere there were trees growing irregularly or in clumps. We met a very stout man, a fine figure, in a Highland bonnet, with a little girl driving home their cow...He told us that the vale was called Strath of Duror and when we said it was a pretty place, he answered, Indeed it was[13]

Duror Parish Church

In 1826, the first Telford Parliamentary church was built in Duror.[14] Since the Reformation, a statutory procedure was put in place in the Parliament of the United Kingdom to build new churches which was overseen by the Commission for Plantation of Kirks. The Church of Scotland had been petitioning to build new churches, but the responsibility to pay for new churches lay with the Heritor, but costs proved prohibitive.[15] In an attempt to meet the Heritor costs halfway, the Additional Places of Worship in the Highlands Act 1823 was passed by parliament, which provided £50000 to build not more than 40 churches in the Highlands, with an annual stipend of £120.[15] Eventually 32 were built with 41 Manses built.[16] Thomas Telford, the Scottish civil engineer, architect and stonemason, and a noted road, bridge and canal builder was employed to build the churches, choosing Duror as the first location.[14] Telford employed the architect, William Thomson who designed the churches, with the stipulation that not more than £1500 was to be spent on each church.[16] Telford managed the task by establish six districts and assigning men to each district. The churches had a classic T-Shape and oblong plan, either one or two storey, adaptable to the local site, and using local materials.[17] In May 1933, the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland passed an act which provided Quoad sacra parish, i.e. territorial districts which the churches would have spiritual jurisdiction.[18] The church in Duror has a healthy congregation.

The efforts were negated though by the Highland Clearances and disruption of 1843 which left churches stranded in remote locations with none or very few in the congregation.[18]

Village of Duror

The village of Duror was originally a series of farming townships called Lagnaha, Achindarroch, Acharn, Achara, Cuil, Keil, and Dalnatrat in the mid 18th century. In the William Roy map of 1746, there is a collection of 6-8 houses clearly seen, located close to Inshaig, along with strips of arable land surrounding it.[19] On the Herman Moll map of 1714, Duror is absent from the map.[20] Dalnatrat, Cuil, Keil are located on the shores of Loch Linnhe. Acharn, Inshaig, Achara, Achindarroch and Lagnaha are situated in the 3 miles (4.8 km) long valley on a North to South bearing, known as the Strath of Duror, which runs from Kentallen in the North about 3 miles (4.8 km) from Duror, making a right turn at the meeting of Glen Duror in south, before meeting the eastern end of Cuil Bay.[7]

The main villages surrounding Duror are Ballachulish, by the abandoned slate quarries on the south shore of Loch Leven, 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast Duror, Onich on the north shore of Loch Leven, and the small settlement of Kentallen, due northeast of Duror.[21] Portnacroish is 6.5 miles (10.5 km) to the southwest.

The Dram Shop

The dram shop (Scottish Gaelic: taigh na h-Insaig) (English:The house of Insaig), situated in Inshaig, on a strip of slightly elevated land, located, on the north bank of River Duror, between the old Mill and the small road that leads to Cuil Bay, was an 18th-century pub and inn in Duror, that was run by Donald Carmicheal.[7] Taigh na h-Insaig was considered a congested place, it was also the home of Donald Carmicheal, as well as his business premises. The pub along with several other dwellings constituted Insaig Township, and who made their living farming the small strip of land. A typical highland pub was described by Scottish engineer Edmund Burt who traveled extensively in the highlands, during the early 18th century. Burt described the pub as follows: Burt recalled having to stable his horses in an outbuilding so weak and small he feared the horses would knock it down. ..."On entering the dwelling house, there the landlady sat, with a parcel of children, some naked, by a little peat fire in the middle of the hut; and over the fireplace was a small hole for the chimney. The floor was common earth, uneven and nowhere dry. ...The walls were about four feet high, lined with sticks wattled like a hurdle, built on the outside with turf. For dinner it was typically 2 or 3 eggs, with nothing else. During dinner, the landlord not only sat down with you, but in some time, ask leaves to introduce his brother or cousin, who all drink your honours health in whisky, which was imbibed from a scallop shell."[7]

Appin Murder

- "What," cried I, "were you in the English army?" "That was I," said Alan. "But I deserted to the right side at Prestonpans, and that's some comfort." Robert Louis Stevenson, Kidnapped

Behind Duror, lies Glen Duror, a short and steep valley that terminates at a bowl of a mountain, that has been eroded by glaciation, at Fraochaidh at 879 m / 2883 ft. At the head of the glen can be found the ruins of the home which belonged to James Stewart, or James Stewart of the Glen as history denotes him.[22]

Callander and Oban Railway

Duror had a railway station that was part of the Callander and Oban Railway. It opened on 24 August 1903 and closed in 1966.

Present day

The principal industry is now tourism in Duror.

Features

Achara Stone

Close to the start of the small road which leads to Cuil bay from Duror Primary School, from the main A828 road, between Duror and the ancient township of Achara (Scottish Gaelic: Achadh a' charraigh), opposite the primary school, within a field, is an ancient single standing stone that has been there for least 5000 years, placed by the previous inhabitants of Duror.[23] The stone is 12 feet (3.7 m) high, and gave its name to the former township of Achara.[24] The stone is impressively large when standing next to it.

Geography

Durors physical geography is dictated by the Ballachulish Igneous Complex, which is located in Argyllshire, 20 km south of Fort William and immediately southeast of the junction of Loch Linnhe and Loch Leven.[21] The Complex is one of the world's most comprehensively studied plutonic-metamorphic systems.[25]

The area of Duror is dominated by Beinn a' Bheithir, is a northward opening, horse-shoe shaped mountain comprising two main peaks, Sgorr Dhearg is a Munro at 1,024 metres (3,360 ft) and Sgorr Dhonuill at 1,001 metres (3,284 ft) is also classed as a Munro, located a mile northwest of Duror. At the base of the northward opening is the tiny village of Lettermore and Ballachulish is located on the north side of Beinn a' Bheithir. To the southeast, across the head of Gleann an Fhiodh, is the peak of Sgorr a' Choise at 658 metres (2,159 ft). To the south, across Glen Duror, is the peak of Fraochaidh at 879 metres (2,884 ft), which is directly north of Duror.[21] To the east of Duror, on the Appin peninsula, the area is much flatter, with the shallow hills of Airds Hill and Beinn Donn being the tallest, at below 500 metres (1,600 ft).

Glaciation has molded the area over the millennia. The hills and mountains contain arête ridges, cols, hanging valleys and truncated spurs. Glen Duror has a U-shaped valley.[21]

Annual rainfall is about 100 inches (2,500 mm) per year, with the driest period being between mid-April to mid-June.[21]

See also

References

- "Duror (Duror of Appin)". The Editors of The Gazetteer for Scotland. The Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Ian Bradley (30 September 2015). Argyll: The Making of a Spiritual Landscape. Saint Andrew Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-86153-838-6. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Tim Clarkson (28 September 2012). "4". The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels and Vikings. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-907909-01-6. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- "NM8944 : Clach Thoull - The Holed Stone". Geograph. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- History, Scottish; read, Archaeology 2 min. "Ballachulish figure". National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- Philip Eden (15 January 2003). The Daily Telegraph Book of the Weather. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8264-7125-3. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- James Hunter (30 September 2011). Culloden And The Last Clansman. Mainstream Publishing. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-78057-362-5. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Hunter, p.21

- Hunter, p.22

- Michael Balfour (21 December 2012). Mysterious Scotland: Enigmas, Secrets and Legends. Mainstream Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-78057-778-4. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Walter Macdougall (2008). Journeying in MacDougall Country. Lulu.com. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-615-17789-2. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Hunter p. 197

- James Hunter (30 September 2011). Culloden And The Last Clansman. Mainstream Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-78057-362-5.

- "Duror Parish Church". Scotlands Churches Trust. Scotlands Churches Trust. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Brian J ORR (2013). Children of the Fasti. Lulu.com. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-291-38929-6.

- Barrett, Richard (3 February 2016). Cycling in the Hebrides. Cicerone Press Limited. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-78362-285-6. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Christopher, John (15 April 2016). Thomas Telford Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4456-5782-0. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Stevenson, John (2 March 2012). Fulfilling a Vision: The Contribution of the Church of Scotland to School Education, 1772-1872. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-61097-344-1.

- "Roy Military Survey of Scotland, 1747-55". National Library of Scotland. British Library. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Cuil, Appin". Scotland Rural Past. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Voll, Gerhard; Töpel, Jutta; Pattison, David R.M. (6 December 2012). Equilibrium and Kinetics in Contact Metamorphism: The Ballachulish Igneous Complex and Its Aureole. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 18. ISBN 978-3-642-76145-4. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Peter Haining (1 September 2011). The Mammoth Book of True Hauntings. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-78033-365-6. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- Clive Ruggles (13 February 2003). Records in Stone: Papers in Memory of Alexander Thom. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-521-53130-6. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- James Hunter (30 September 2011). Culloden And The Last Clansman. Mainstream Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-78057-362-5. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- D R M, Pattison; B, Harte (2001). "Ballachulish Igneous Complex - setting and summary of geology". British Geological Survey. Edinburgh Geological Society. Earthwise. Retrieved 17 October 2017.