Hymenolepis nana

Dwarf tapeworm (Hymenolepis nana, also known as Rodentolepis nana, Vampirolepis nana, Hymenolepis fraterna, and Taenia nana) is a cosmopolitan species though most common in temperate zones, and is one of the most common cestodes (a type of intestinal worm or helminth) infecting humans, especially children.

| Dwarf tapeworm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult dwarf tapeworm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Cestoda |

| Order: | Cyclophyllidea |

| Family: | Hymenolepididae |

| Genus: | Hymenolepis |

| Species: | H. nana |

| Binomial name | |

| Hymenolepis nana | |

Morphology

As its name implies (Ancient Greek: νᾶνος, nānos – dwarf), it is a small species, seldom exceeding 40 mm long and 1 mm wide. The scolex bears a retractable rostellum armed with a single circle of 20 to 30 hooks. The scolex also has four suckers, or a tetrad. The neck is long and slender, and the segments are wider than long. Genital pores are unilateral, and each mature segment contains three testes. After apolysis, gravid segments disintegrate, releasing eggs, which measure 30 to 47 µm in diameter. The oncosphere is covered with a thin, hyaline, outer membrane and an inner, thick membrane with polar thickenings that bear several filaments. The heavy embryophores that give taeniid eggs their characteristic striated appearance are lacking in this and the other families of tapeworms infecting humans. The rostellum remains invaginated in the apex of the organ. Rostellar hooklets are shaped like tuning forks. The neck is long and slender, the region of growth. The strobila starts with short, narrow proglottids, followed with mature ones.

Life cycle

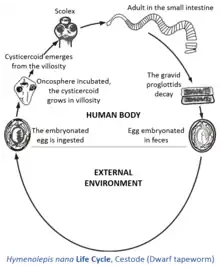

Infection is acquired most commonly from eggs in the feces of another infected individual, which are transferred in food, by contamination. Eggs hatch in the duodenum, releasing oncospheres, which penetrate the mucosa and come to lie in lymph channels of the villi. An oncosphere develops into a cysticercoid which has a tail and a well-formed scolex. It is made of longitudinal fibers and is spade-shaped with the rest of the worm still inside the cyst. In five to six days, cysticercoids emerge into the lumen of the small intestine, where they attach and mature.

The direct life cycle is doubtless a recent modification of the ancestral two-host life cycle found in other species of hymenolepidids, because cysticercoids of H. nana can still develop normally within larval fleas and beetles. One reason for facultative nature of the life cycle is that H. nana cysticercoids can develop at higher temperatures than can those of the other hymenolepidids. Direct contaminative infection by eggs is probably the most common route in human cases, but accidental ingestion of an infected grain beetle or flea cannot be ruled out. The direct infectiousness of the eggs frees the parasite from its former dependence upon an insect intermediate host, making rapid infection and person-to-person spread possible. The short lifespan and rapid course of development also facilitate the spread and ready availability of this worm.

Reproduction

Hymenolepis nana, like all tapeworms, contains both male and female reproductive structures in each proglottid. This means that the dwarf tapeworm, like other tapeworms is hermaphroditic. Each segment contains three testes and a single ovary. When a proglottid becomes old and unable to absorb any more nutrition, it is released and is passed through the host's digestive tract. This gravid proglottid contains the fertilized eggs, which are sometimes expelled with the feces. However, most of the time, the egg may also settle in the microvilli of the small intestine, hatch, and the larvae can develop to sexual maturity without ever leaving the host.

Behavior

The dwarf tapeworm, like all other tapeworms, lacks a digestive system and feeds by absorption on nutrients in the intestinal lumen. They have nonspecific carbohydrate requirements and they seem to absorb whatever is being passed through the intestine at that time. When it becomes an adult, it attaches to the intestinal walls with its suckers and toothed rostellum and has its segments reaching out into the intestinal space to absorb food.

Epidemiology

The dwarf tapeworm or Hymenolepis nana is found worldwide. More common in warm parts of South Europe, Russia, India, US and Latin America. Infection is most common in children, in persons living in institutional settings, crowded environments and in people who live in areas where sanitation and personal hygiene is inadequate. Infection is most common in children aged 4–10 years, in dry, warm regions of the developing world. Estimated to have 50-75 million carriers of Hymenolopis nana with 5 to 25% prevalence in children worldwide. One becomes infected by accidentally ingesting dwarf tapeworm eggs, ingesting fecally contaminated foods or water, by touching your mouth with contaminated fingers, or by ingesting contaminated soil, and/or accidentally ingesting an infected arthropod.

United States:

- Infection is most common in the Southeast

- Infection rates were found to be higher among Southeast Asian refugees in the United States

International:

- Regions with high reported infection rates include Sicily (46%), Argentina (34% of school children), and southern areas of the former Soviet Union (26%)

Pathogenesis

Light infections:

- Asymptomatic

Heavy infections:

- Toxemia

- Significant intestinal inflammation

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Weakness

- Loss of appetite

For young children:

- Head-ache

- Itchy buttocks

- Difficulty sleeping

Treatment

The prescription drug Praziquantel is usually prescribed in a single dose to patients infected with H.nana. Praziquantel is widely used and preferred due to its high efficacy. Research has shown that the cysticercoid phase of H.nana's life cycle is the most susceptible to the Praziquantel treatment.[2]

In 1980, research proved that Praziquantel had morphological effects on H.nana and other similar cestodes. Following ten minutes of Praziquantel administration, H. nana was almost completely paralyzed; thirty minutes post-administration, the tapeworms were completely dislodged from the caecum. This research fully indicated the paralyzing and deadly nature of Praziquantel on H. nana, H. diminuta, H. microstoma.[3]

History

In 1887, Grassi demonstrated that transmission from rat to rat did not require an intermediate host.[4] Later, in 1921, Saeki demonstrated a direct cycle of transmission of H. nana in humans, transmission without an intermediate host. In addition to the direct cycle, Nicholl and Minchin demonstrated that fleas can serve as intermediate hosts between humans.[5]

References

- Deaderick, William H. (1906). "Hymenolepis Nana and Hymenolepis Diminuta, with Report of Cases". Journal of the American Medical Association. XLVII (25): 2087–2090. doi:10.1001/jama.1906.25210250041002.

- "Hymenolepis Nana - Dwarf Tapeworm". www.parasitesinhumans.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- Chai, Jong-Yil (March 2013). "Praziquantel Treatment in Trematode and Cestode Infections: An Update". Infection & Chemotherapy. 45 (1): 32–43. doi:10.3947/ic.2013.45.1.32. ISSN 2093-2340. PMC 3780935. PMID 24265948.

- Grassi B. Entwicklungscyclus der Taenia nanna. Dritte Praliminarnote. Centralblatt fṻr Bakteriologie und Parasitenkunde 1887;2:305-312.

- Marty AM and Neafie RC Hymenolepiasis and Miscellaneous Cyclophyllidiases pages 197–214 in Meyers WM, Neafie RC, Marty AM, Wear DJ. (Eds) Pathology of Infectious Diseases Volume I Helminthiases. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC. 2000; "Item FS28". Archived from the original on 2010-12-27. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- 6. Arora, H. S. (2017, January 6). Hymenolepiasis. Retrieved December 8, 2017, from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/998498-overview#a6

- 7. C. (2012, January 10). Hymenolepiasis FAQs. Retrieved December 8, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/hymenolepis/faqs.html

Further reading

- Ohio State University, 2001. "Hymenolepis nana (Vampirolepsis nana)" (on-line). Parasites and Parasitological Resources. Accessed October 14, 2004 at https://web.archive.org/web/20060208102212/http://www.biosci.ohio-state.edu/~parasite/hymenolepis_nana.html.

- "Hymenolepiasis." https://web.archive.org/web/20091103162725/http://health.allrefer.com/. D. Scott Smith, MD, MSc, DTM&H, Infectious Diseases Division and Dept. of Microbiology and Immunology, Stanford University Medical School, Stanford, CA. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network., 18 Nov. 2003. Web. 25 Sept. 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20110707113919/http://health.allrefer.com/health/hymenolepiasis-info.html.

- Chero JC, Saito M, Bustos JA, Blanco EM, Gonzalvez G, Garcia HH. Hymenolepis nana infection: symptoms and response to nitazoxanide in field conditions. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. Feb 2007;101(2):203-5. [Medline].

- Baron S., (1996). Medical Microbiology. (4th edition). The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- Gerald D. Schmidt, John Janovy, Jr and Larry S. Roberts (2009). Foundations of Parasitology (8th ed). McGraw-Hil. ISBN 0-07-302827-4

- R. D. PEARSON, and R. L. GUERRANT. Praziquantel: A Major Advance in Anthelminthic Therapy. Ann Intern Med, August 1, 1983; 99(2): 195–198.

- World Health Organization (1995). WHO model prescribing information: drugs used in parasitic diseases (2nd edition). Published by World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-140104-4