Eötvös effect

The Eötvös effect is the change in measured Earth's gravity caused by the change in centrifugal acceleration resulting from eastbound or westbound velocity. When moving eastbound, the object's angular velocity is increased (in addition to Earth's rotation), and thus the centrifugal force also increases, causing a perceived reduction in gravitational force.

Discovery

In the early 1900s, a German team from the Geodetic Institute of Potsdam carried out gravity measurements on moving ships in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans. While studying their results, the Hungarian nobleman and physicist Baron Roland von Eötvös (Loránd Eötvös) noticed that the readings were lower when the boat moved eastwards, higher when it moved westward. He identified this as primarily a consequence of Earth's rotation. In 1908, new measurements were made in the Black Sea on two ships, one moving eastward and one westward. The results substantiated Eötvös' claim.

Formulation

Geodesists use the following formula to correct for velocity relative to Earth during a gravimetric run.

Here,

- is the relative acceleration

- is the rotation rate of the Earth

- is the velocity in longitudinal direction (east-west)

- is the latitude where the measurements are taken.

- is the velocity in latitudinal direction (north-south)

- is the radius of the Earth

The first term in the formula, 2Ωu cos(ϕ), corresponds to the Eötvös effect. The second term is a refinement that under normal circumstances is much smaller than the Eötvös effect.

Physical explanation

The most common design for a gravimeter for field work is a spring-based design; a spring that suspends an internal weight. The suspending force provided by the spring counteracts the gravitational force. A well-manufactured spring has the property that the amount of force that the spring exerts is proportional to the extension of the spring from its equilibrium position (Hooke's law). The stronger the effective gravity at a particular location, the more the spring is extended; the spring extends to a length at which the internal weight is sustained. Also, the moving parts of the gravimeter will be dampened, to make it less susceptible to outside influences such as vibration.

For the calculations it will be assumed that the internal weight has a mass of ten kilograms (10 kg; 10,000 g). It will be assumed that for surveying a method of transportation is used that gives good speed while moving very smoothly: an airship. Let the cruising velocity of the airship be 25 metres per second (90 km/h; 56 mph).

Motion along the equator

To calculate what it takes for the internal weight of a gravimeter to be neutrally suspended when it is stationary with respect to the Earth, the Earth's rotation must be taken into account. At the equator, the velocity of Earth's surface is about 465 metres per second (1,674 km/h; 1,040 mph). The amount of centripetal force required to cause an object to move along a circular path with a radius of 6378 kilometres (the Earth's equatorial radius), at 465 m/s, is about 0.034 newtons per kilogram of mass. For a 10,000-gram internal weight, that amounts to about 0.34 newtons. The amount of suspension force required is the mass of the internal weight (multiplied by the acceleration of gravity) minus those 0.34 newtons. In other words: any object co-rotating with the Earth at the equator has its measured weight reduced by 0.34 percent, thanks to the Earth's rotation.

When cruising at 10 m/s due East, the total velocity becomes 465 + 10 = 475 m/s, which requires a centripetal force of about 0.0354 newtons per kilogram. Cruising at 10 m/s due West the net velocity is 465 − 10 = 455 m/s, requiring about 0.0325 newtons per kilogram. So if the internal weight is neutrally suspended while cruising due East, after reversing course it will not be neutrally suspended any more: the apparent mass of the 10,000-gram internal weight will increase by about 3 grams, and the spring of the gravimeter must extend some more to accommodate this greater weight.

In high-performance meteorological models, this effect needs to be taken into account on a terrestrial scale. Air masses with significant velocity with respect to the Earth have a tendency to migrate to another altitude, and when the accuracy demands are strict this must be taken into account.

Derivation of the formula for simplified case

Derivation of the formula for motion along the Equator.

A convenient coordinate system in this situation is the inertial coordinate system that is co-moving with the center of mass of the Earth. Then the following is valid: objects that are at rest on the surface of the Earth, co-rotating with the Earth, are circling the Earth's axis, so they are in centripetal acceleration with respect to that inertial coordinate system.

What is sought is the difference in centripetal acceleration of the surveying airship between being stationary with respect to the Earth and having a velocity with respect to the Earth. The following derivation is exclusively for motion in east–west or west–east direction.

Notation:

- is the total centripetal acceleration when moving along the surface of the Earth.

- is the centripetal acceleration when stationary with respect to the Earth.

- is the angular velocity of the Earth: one revolution per Sidereal day.

- is the angular velocity of the airship relative to the angular velocity of the Earth.

- is the total angular velocity of the airship.

- is the airship's velocity (velocity relative to the Earth).

- is the Earth's radius.

It can readily be seen that the formula above for motion along the equator follows from the more general equation below for any latitude where along the equator v = 0.0 and

The second term represents the required centripetal acceleration for the airship to follow the curvature of the Earth. It is independent of both the Earth's rotation and the direction of motion. For example, when an aeroplane carrying gravimetric reading instruments cruises over one of the poles at constant altitude, the aeroplane's trajectory follows the curvature of the Earth. The first term in the formula is zero then, due to the cosine of the angle being zero, and the second term then represents the centripetal acceleration to follow the curvature of the Earth's surface.

Explanation of the cosine in the first term

The mathematical derivation for the Eötvös effect for motion along the Equator explains the factor 2 in the first term of the Eötvös correction formula. What remains to be explained is the cosine factor.

Because of its rotation, the Earth is not spherical in shape, there is an Equatorial bulge. The force of gravity is directed towards the center of the Earth. The normal force is perpendicular to the local surface.

On the poles and on the equator the force of gravity and the normal force are exactly in opposite direction. At every other latitude the two are not exactly opposite, so there is a resultant force, that acts towards the Earth's axis. At every latitude there is precisely the amount of centripetal force that is necessary to maintain an even thickness of the atmospheric layer. (The solid Earth is ductile. Whenever the shape of the solid Earth is not entirely in equilibrium with its rate of rotation, then the shear stress deforms the solid Earth over a period of millions of years until the shear stress is resolved.)

Again the example of an airship is convenient for discussing the forces that are at work. When the airship has a velocity relative to the Earth in latitudinal direction then the weight of the airship is not the same as when the airship is stationary with respect to the Earth.

If an airship has an eastward velocity, then the airship is in a sense "speeding". The situation is comparable to a racecar on a banked circuit with an extremely slippery road surface. If the racecar is going too fast then the car will drift wide. For an airship in flight that means a reduction of the weight, compared to the weight when stationary with respect to the Earth.

If the airship has a westward velocity then the situation is like that of a racecar on a banked circuit going too slow: on a slippery surface the car will slump down. For an airship that means an increase of the weight.

The first term of the Eötvös effect is proportional to the component of the required centripetal force perpendicular to the local Earth surface, and is thus described by a cosine law: the closer to the Equator, the stronger the effect.

Motion along 60 degrees latitude

The same gravimeter is used again, its internal weight has a mass of 10,000 grams.

Calculating the weight reduction when stationary with respect to the Earth:

An object located at 60 degrees latitude, co-moving with the Earth, is following a circular trajectory, with a radius of about 3190 kilometer, and a velocity of about 233 m/s. That circular trajectory requires a centripetal force of about 0.017 newton for every kilogram of mass; 0.17 newton for the 10,000 gram internal weight. At 60 degrees latitude, the component that is perpendicular to the local surface (the local vertical) is half the total force. Hence, at 60 degrees latitude, any object co-moving with the Earth has its weight reduced by about 0.08 percent, thanks to the Earth's rotation.

Calculating the Eötvös effect:

When the airship is cruising at 25 m/s towards the east the total velocity becomes 233 + 25 = 258 m/s, which requires a centripetal force of about 0.208 newton; local vertical component about 0.104 newton. Cruising at 25 m/s towards the west the total velocity becomes 233 − 25 = 208 m/s, which requires a centripetal force of about 0.135 newton; local vertical component about 0.068 newton. Hence at 60 degrees latitude the difference before and after the U-turn of the 10,000 gram internal weight is a difference of 4 grams in measured weight. (Popularly spoken as the weight is a force being measured in newtons, not in grams.)

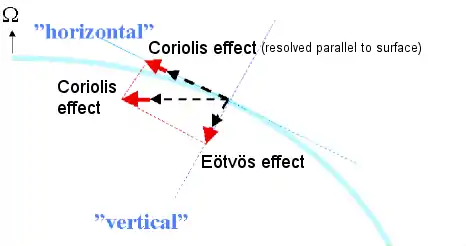

The diagrams also show the component in the direction parallel to the local surface. In meteorology and in oceanography, it is customary to refer to the effects of the component parallel to the local surface as the Coriolis effect.

References

- The Coriolis effect PDF-file. 870 KB 17 pages. A general discussion by the meteorologist Anders Persson of various aspects of geophysics, covering the Coriolis effect as it is taken into account in Meteorology and Oceanography, the Eötvös effect, the Foucault pendulum, and Taylor columns.

External links

- In 1915 Eötvös constructed a tabletop device Archived 2015-06-07 at the Wayback Machine that demonstrates the Eötvös effect. The device is among other instruments on display in a small museum that is dedicated to the work and the life of Eötvös.

- Larger picture of the tabletop device from the museum website.