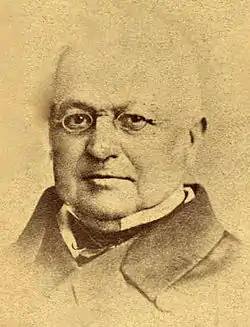

Eliakim Carmoly

Eliakim Carmoly (5 August 1802 in Soultz-Haut-Rhin, France – 15 February 1875 in Frankfurt) was a French scholar. He was born at Soultz-Haut-Rhin, then in the French department of Haut-Rhin. His real name was Goschel David Behr (or Baer); the name Carmoly, borne by his family in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, was adopted by him when quite young. He studied Hebrew and Talmud at Colmar; and, because both French and German were spoken in his native town, he became proficient in those languages.

Carmoly went to Paris, and there assiduously studied the old Hebrew manuscripts in the Bibliothèque Nationale, where he was employed. Several articles published by him on various subjects in scientific papers made him known; and on the establishment of a Jewish consistory in Belgium, he was appointed rabbi at Brussels (18 May 1832). In this position Carmoly rendered many services to the newly founded congregation, chiefly in providing schools for the poor. Seven years later, having provoked great opposition by his new scheme of reforms, Carmoly resigned the rabbinate and retired to Frankfort, where he devoted himself wholly to Jewish literature and to the collection of Hebrew books and manuscripts, in which he was passionately interested.

His grandfather was Isaachar Bär ben Judah Carmoly, rabbi of Sulz.

Works

Carmoly was the author of the following works:

- Toledot Gedole Yisrael, a biographical dictionary of eminent Jews, ancient and modern, Metz, 1828 (only one volume, extending to "Aaron ben Chayyim," was published)

- Wessely et Ses Écrits, Nancy, 1829

- Sibbub Rab Petachyah, the travels of Petachiah of Ratisbon, translated into French and accompanied by the Hebrew text, Paris, 1831

- Eldad ha-Dani: Relation d'Eldad le Danite, Voyageur du IXe; Siècle, Traduit en Français, Suivie du Texte et de Notes, Brussels, 1834

- Mémoire sur un Médaillon en l'Honneur de Louis-le-Débonnaire, ibid. 1839

- Maimonides und Seine Zeitgenossen, translated from the Hebrew into German, Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1840

- Les Mille et Un Contes, Récits Chaldéens, Brussels, 1842

- 'Aqtan de-Mar Ya'aqob, a kind of Midrash in six chapters on the Khazars, published for the first time from two manuscripts, ibid. 1842

- Eldad et Medad, ou le Joueur Converti, translated from Leo di Modena's work, with a biographical notice on the author, ibid. 1844

- Le Jardin Enchanté, Contes, ibid. 1845

- Sefer ha-Kuzarim: Des Khozars au Xe; Siècle, Suivi d'une Lettre du Ministre d'Abd el-Rachman III. au Roi de Khozarie et la Réponse du Prince, ibid. 1845

- Histoire des Médecins Juifs, Anciens et Modernes, ibid. 1844

- Halikot Eretz Yisrael: Itinéraires de la Terre Sainte des XIIIe-XVIIe Siècles, translated from the Hebrew, ibid. 1847

- Dibre ha-Yamim le-Bene Yachya [Yahya], genealogy and biography of the Yachya family, Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1850

- Ha-'Orebim u-Bene Yonah (The Crows and the Doves), genealogy of the Rapoport family, Rödelheim, 1861

- Imre Shefer (Words of Beauty), on Hebrew versification, by Abshalom Mizrachi (fourteenth century), with an introduction and an appendix containing literary essays and poems by the editor, Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1868

- La France Israélite; Mémoire pour Servir à l'Histoire de Notre Littérature, Paris, 1858

- Mebasseret Tzion (O Zion, That Bringest Good Tidings), a collection of letters from Jerusalem on the Lost Ten Tribes, Brussels, 1841

Besides these works, Carmoly contributed to many periodicals, and edited the Revue Orientale (Brussels, 1841–46, 3 vols.), in which most of the articles were furnished by himself. The most important of these contributions, which constitute works by themselves, were:

- "Vocabulaire de la Géographie Rabbinique de France"

- "Essai sur l'Histoire des Juifs en Belgique"

- "Mille Ans des Annales Israélites d'Italie"

- "De l'Etat des Israélites en Pologne"*

- "Des Juifs du Maroc, d'Alger, de Tunis, et de Tripoli, Depuis Leur Etablissement dans Ces Contrées Jusqu'à Nos Jours"

Controversy

Carmoly has been accused of fabrications by several scholars.[1] In particular, his itinerary of Isaac Chelo is commonly believed to be a forgery.[2] According to the Jewish Encyclopedia: "Carmoly's works have been severely attacked by the critics; and it must be admitted that his statements can not always be relied upon. Still, he rendered many services to Jewish literature and history; and the mistrust of his works is often unfounded."[3]

References

- Roth, Cecil (2007). "Forgeries". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 7 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- Dan D. Y. Shapira (2006). "Remarks on Avraham Firkowicz and the Hebrew Mejelis "Document"". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 59 (2): 131–180. doi:10.1556/AOrient.59.2006.2.1.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "CARMOLY, ELIAKIM". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "CARMOLY, ELIAKIM". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Isidore Singer and Isaac Broydé (1901–1906). "Carmoly, Eliakim". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Isidore Singer and Isaac Broydé (1901–1906). "Carmoly, Eliakim". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.