Eastern Zhou

The Eastern Zhou (/dʒoʊ/;[1] Chinese: 東周; pinyin: Dōngzhōu; Wade–Giles: Tung1-chou1; 771–256[2] BC) is a period of Chinese history, approximately the second half of the Zhou dynasty, following the Western Zhou period. Characterised by weak central government, it is subdivided into two periods: the Spring and Autumn, during which the ancient aristocracy still held power in a large number of separate polities, and the Warring States, which saw the consolidation of territory into a few domains and the dominance of other social classes. "Eastern" refers to the geographic situation of the royal capital, near present-day Luoyang.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

History

In 770 BCE, the capital of the Zhou Kingdom was moved from Haojing (Chang'an County in Xi'an City) to Luoyi (known today as Luoyang, Henan Province).

This brought about the beginning of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (as opposed to Western Zhou dynasty), so named due to Luoyi being situated to the east of Haojing. Over 25 kings reigned over the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, lasting 515 years in all.

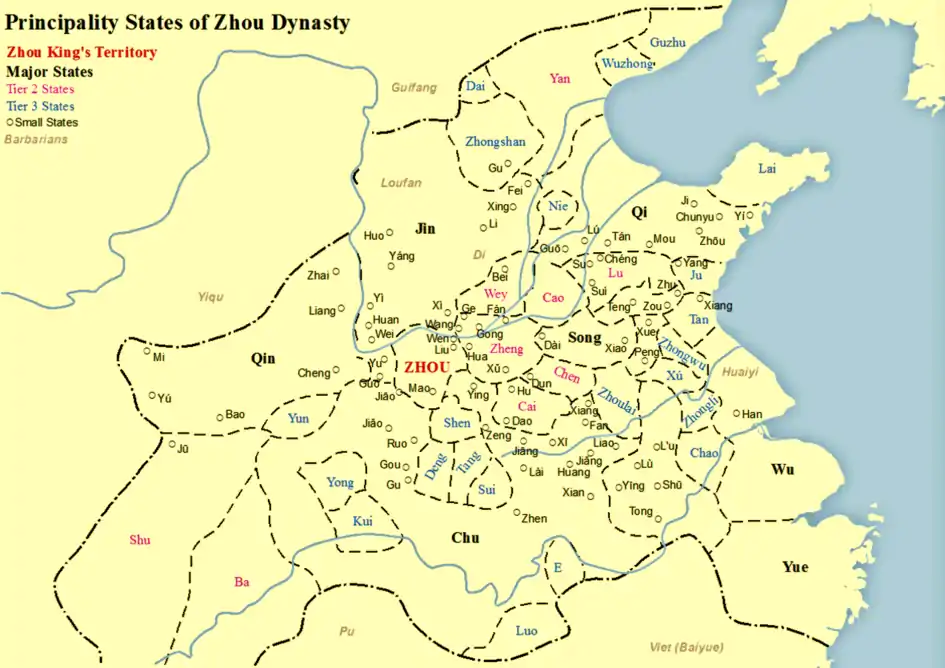

With the death of King You of Zhou,[3] the last king of the Western Zhou Dynasty, Crown Prince Yijiu was proclaimed the new king by the nobles from the states of Zheng, Lü, Qin and the Marquess of Shen. He became King Ping of Zhou. In the second year of his reign, he moved the capital east to Luoyi as Quanrong invaded Haojing, spelling the end of the Western Zhou dynasty. The first half of the Eastern Zhou dynasty, from approximately 771 to 476 BCE, was called the Spring and Autumn period, during which more and more dukes and marquesses obtained regional autonomy, defying the king's court in Luoyi, and waging wars amongst themselves. The second half of the Eastern Zhou dynasty, from 475 to 221 BCE, was called the Warring States period,[3] during which the King of Zhou gradually lost his power and ruled merely as a figurehead.

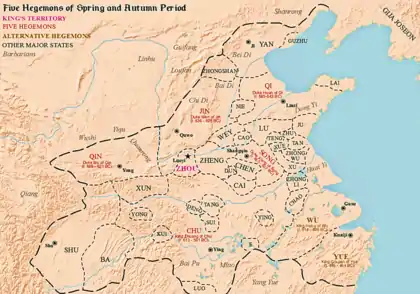

After moving the capital east, the Zhou royal family fell into a state of decline. Also, King Ping's popularity fell as rumors went that he had killed his father. With vassals becoming increasingly powerful, strengthening their position through defeating other rival states, and increasing invasion from neighboring countries, the king of Zhou was not able to master the country. Constantly, he would have to turn to the powerful vassals for help. The most important vassals (known later as the twelve vassals) came together in regular conferences where they decided important matters, such as military expeditions against foreign groups or against offending nobles.[4] During these conferences one vassal ruler was sometimes declared hegemon. Chancellor Guan Zhong of Qi initiated a policy "Revere the king, expel the barbarians" (Chinese: 尊王攘夷, see Sonnō jōi). Adopting and adhering to it, Duke Huan of Qi assembled the vassals to strike down the threat of barbarians from the country. During the Warring States period, many of the leaders of the vassals' clamoring for kingship further limited the Zhou royal family's influence.[5]

In 635 BCE, the Chaos of Prince Dai took place. King Xiang of Zhou turned to Duke Wen of Jin for help, who killed Prince Dai and was rewarded with rule over Henei and Yangfan.[3] In 632 BCE, King Xiang of Zhou was forced by Duke Wen of Jin to attend the conference of vassals in Jiantu.[3]

In 606 BCE, King Zhuang of Chu inquired for the first time regarding the "weight of the cauldrons" (問鼎之輕重) only to be rebuffed by the Zhou minister Wangsun Man (王孫滿).[3] Asking such a question was at that time a direct challenge to the power of the reigning dynasty.

At the time of King Nan of Zhou, the kings of Zhou had lost almost all political and military power, as even their remaining crown land was split into two states or factions, led by rival feudal lords: West Zhou, where the capital Wangcheng was located, and East Zhou, centered at Chengzhou and Kung. King Nan of Zhou managed to preserve his weakened dynasty through diplomacy and conspiracies for fifty-nine years until his deposition and death by Qin in 256 BCE. Seven years later, West Zhou was conquered by Qin.[3]

Politics

This period marked a big turn in Chinese history, as the dominant toolmaking material became iron by the end of the period. The Eastern Zhou period was believed to be the beginning of the Iron Age in China.

There was a considerable development in agriculture with a consecutive increase in population. There were constantly fights between vassals to scramble for lands or other resources. People started using copper coins. Education was made universal for civilians. The boundaries between the nobility and the civilians subsided. A revolutionary transformation of the society was taking place, to which the patriarchal clan system made by the Zhou Dynasty could no longer adapt.[6]

Kings

- King Ping of Zhou — Ji Yijiu (772 BCE–720 BCE)

- King Xie of Zhou — Ji Yuchen (770 BCE–760 BCE or 771 BCE–750 BCE)

- King Huan of Zhou — Ji Lin (719 BCE–697 BCE)

- King Zhuang of Zhou — Ji Tuo (696 BCE–682 BCE)

- King Xi of Zhou — Ji Huqi (681 BCE–677 BCE)

- King Hui of Zhou — Ji Lang (676 BCE–652 BCE)

- King Xiang of Zhou — Ji Zheng (651 BCE–619 BCE)

- King Qing of Zhou — Ji Renchen (618 BCE–613 BCE)

- King Kuang of Zhou — Ji Ban (612 BCE–607 BCE)

- King Ding of Zhou — Ji Yu (606 BCE–586 BCE)

- King Jian of Zhou — Ji Yi (585 BCE–572 BCE)

- King Ling of Zhou — Ji Xiexin (571 BCE–545 BCE)

- King Jing of Zhou — Ji Gui (544 BCE–520 BCE)

- King Dao of Zhou — Ji Meng (520 BCE)

- King Jing of Zhou — Ji Gai (519 BCE–477 BCE)

- King Yuan of Zhou — Ji Ren (476 BCE–469 BCE)

- King Zhending of Zhou — Ji Jie (468 BCE–441 BCE)

- King Ai of Zhou — Ji Quji (441 BCE)

- King Si of Zhou — Ji Shu (441 BCE)

- King Kao of Zhou — Ji Wei (440 BCE–426 BCE)

- King Weilie of Zhou — Ji Wu (425 BCE–402 BCE)

- King An of Zhou — Ji Jiao (401 BCE–376 BCE)

- King Lie of Zhou — Ji Xi (375 BCE–369 BCE)

- King Xian of Zhou — Ji Bian (368 BCE–321 BCE)

- King Shenjing of Zhou — Ji Ding (320 BCE–315 BCE)

- King Nan of Zhou — Ji Yan (314 BCE–256 BCE)

Spring and Autumn period

The period's name derives from the Spring and Autumn Annals, a chronicle of the state of Lu between 722 and 479 BCE, which tradition associates with Confucius.

During this period, the Zhou royal authority over the various feudal states started to decline, as more and more dukes and marquesses obtained de facto regional autonomy, defying the king's court in Luoyi, and waging wars amongst themselves. The gradual partition of Jin, one of the most powerful states, marked the end of the Spring and Autumn period, and the beginning of the Warring States period.

Warring States period

The Warring States period was an era in ancient Chinese history following the Spring and Autumn period and concluding with the Qin wars of conquest. Those wars resulted in the annexation of all other contender states, completed with the Qin state's victory in 221 BCE. That meant that the Qin state became the first unified Chinese empire, known as the Qin dynasty.

References

Citations

- "Zhou". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- "...Eastern Zhou period (770–256 BC)" Early China - A Social and Cultural History, p. 10. Cambridge University Press.

- Chien, Szuma (October 1979). Records of the Historians. ISBN 978-0835106184.

- "Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770 BC-221 BC) in China History". www.warriortours.com. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- "Zhou Dynasty". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- 黄仁宇:《中国大历史》

- "The British Museum Images". British Museum Images.

- Khayutina, Maria (Autumn 2013). "From wooden attendants to terracotta warriors" (PDF). Bernisches Historisches Museum The Newsletter. No.65: 2, Fig.4.

Other noteworthy terracotta figurines were found in 1995 in a 4th-3rd century BCE tomb in the Taerpo cemetery near Xianyang in Shaanxi Province, where the last Qin capital of the same name was located from 350 to 207 BCE. These are the earliest representations of cavalrymen in China discovered up to this day. One of this pair can now be seen at the exhibition in Bern (Fig. 4). A small, ca. 23 cm tall, figurine represents a man sitting on a settled horse. He stretches out his left hand, whereas his right hand points downwards. Holes pierced through both his fists suggest that he originally held the reins of his horse in one hand and a weapon in the other. The rider wears a short jacket, trousers and boots – elements of the typical outfit of the inhabitants of the Central Asian steppes. Trousers were first introduced in the early Chinese state of Zhao during the late 4th century BCE, as the Chinese started to learn horse riding from their nomadic neighbours. The state of Qin should have adopted the nomadic clothes about the same time. But the figurine from Taerpo also has some other features that may point to its foreign identity: a hood-like headgear with a flat wide crown framing his face and a high, pointed nose.

Also in Khayutina, Maria (2013). Qin: the eternal emperor and his terracotta warriors (1. Aufl ed.). Zürich: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. p. cat. no. 314. ISBN 978-3-03823-838-6. - Duan Qingbo (January 2023). "Sino-Western Cultural Exchange as Seen through the Archaeology of the First Emperor's Necropolis" (PDF). Journal of Chinese History. 7 (1): 26 Fig.1, 27. doi:10.1017/jch.2022.25.

In terms of formal characteristics and style of dress and adornment, the closest parallels to the Warring States-period Qin figurines are found in the Scythian culture. Wang Hui 王輝 has examined the exchanges between the cultures of the Yellow River valley and the Scythian culture of the steppe. During a 2007 exhibition on the Scythians in Berlin, there was a bronze hood on display labeled a "Kazakh military cap." This bronze hood and the clothing of the nomads in kneeling posture [also depicted in the exhibition] are very similar in form to those of the terracotta figurines from the late Warring States Qin-period tomb at the Taerpo site (see Figure 1). The style of the Scythian bronze horse figures and the saddle, bridle, and other accessories on their bodies are nearly identical to those seen on the Warring States-period Qin figurines and a similar type of artifact from the Ordos region, and they all date to the fifth to third centuries BCE.

- Rawson, Jessica (April 2017). "China and the steppe: reception and resistance". Antiquity. 91 (356): 386. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.276.

King Zheng of Qin (246–221 BC), who was to be the First Emperor (221–210 BC), took material from many regions. As he unified the territory, he employed steppe cavalry men in his army, as we now recognise from the terracotta warriors guarding his tomb (Khayutina 2013: cat. no. 314), whose dress resembles that of the steppe leaders known to the Achaemenids and Parthians (Curtis 2000: front cover), but he proclaimed his conquest in the language of the Central Plains: Chinese. The First Emperor must have had advisors who knew something of the seals, weights and measures of Central Asia and Iran (Khayutina 2013: cat. nos 115–17), and also retained craftsmen who had mastered Western technologies and cast bronze birds for his tomb in hitherto unknown life-like forms (Mei et al. 2014). He also exploited mounted horsemen and iron weaponry originally from the steppe, and agriculture and settlements of the Central Plains, turning to the extraordinary organisation of people and manufacturing from this area to create a unified state. This could only be achieved by moving towards the centre, as the Emperor indeed did.

Sources

- 許倬雲 著,鄒水傑 譯:《中國古代社會史論——春秋戰國時期的社會流動》(桂林:廣西師範大學出版社,2006).

- Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang (1974), Records of the Historians. Hong Kong: Commercial Press.

- Reprinted by University Press of the Pacific, 2002. Contains biographies of Confucius and Laozi. ISBN 978-0835106184.