Economy of Austria-Hungary

The economy of Austria-Hungary changed slowly during the existence of the Dual Monarchy, 1867-1918. The capitalist way of production spread throughout the Empire during its 50-year existence replacing medieval institutions. In 1873, the old capital Buda and Óbuda (Ancient Buda) merged with the third city, Pest, thus creating the new metropolis of Budapest. The dynamic Pest grew into Hungary's administrative, political, economic, trade and cultural hub. Many of the state institutions and the modern administrative system of Hungary were established during this period.

Austria-Hungary was a large, heavily rural country with wealth and income levels a bit below the European average. Growth rates were similar to Europe as a whole. After 1895. migration became a major factor, with most headed to the United States.

Background

The Habsburg realms included 23 million inhabitants in 1800, growing to 36 million by 1870, third in population size behind Russia and Germany.[1] Nationally the per capita rate of industrial growth averaged about 3% between 1818 and 1870. However there were strong regional differences. That was relatively little international trade. In the Alpine and Bohemian regions, proto-industrialization at begun by 1750, and became the center of the first phases of the industrial revolution after 1800. The textile industry was the main factor, utilizing mechanization, steam engines, and the factory system. Much of machinery was purchased from the British. In the Bohemian regions, machine spinning started later and only became a major factor by 1840. Bohemia's resources were successfully exploited, growing 10% a year. The iron industry had developed in the Alpine regions after 1750, with smaller centers in Bohemia and Moravia. Key factors included the replacement of charcoal by coal, introduction of steam engine, and the rolling regard. The first steam engine appeared in 1816 but the abundance of water power slowed its dissemination. Hungary was heavily rural with little industry before 1870.[2][3] The first machine building factories appeared in the 1840s.

Economic trends 1870-1913

Technological change accelerated industrialization and urbanization. The GNP per capita grew roughly 1.76% per year from 1870–1913. That level of growth compared very favorably to that of other European nations such as Britain (1%), France (1.06%), and Germany (1.51%).[4] However, in a comparison with Germany and Britain: the Austro-Hungarian economy as a whole still lagged considerably, as sustained modernization had begun much later.

By 1913, the population of Austria-Hungary was 48 million, compared to 171 million in Russia, 67 million in Germany, 40 million in France, and 35 million in Italy, as well as 98 million in the United States. The population was heavily rural, with 67% of the workforce in agriculture in 1870, and 60% in 1913. They concentrated in grain production, not livestock. Only 16% of the workforce was employed by industry in 1870, rising to 22%. The output of coal, iron and beer was comparable to Belgium, which had only one sixth the population.[5]

Foreign investment in the Empire, 1870 to 1913, was dominated by Germany, followed by France, and to a lesser extent Great Britain. However Austria exported more capital than it imported. Foreign trade during this period, imports plus exports, averaged about a fourth of Austria's GNP. To protect its growing industries, Vienna raised tariffs in the 1870s and 1880s . As a result economic growth was strong as the GNP doubled from 1870 to 1913. Austria-Hungary grew by 93%, compared to growth of 115% for the remainder of Europe. Per capita growth of wealth was slightly higher than the rest of Europe.[6]

Geographical variation

Economic growth centered on Vienna, Budapest and Prague, as well as the Austrian lands (areas of modern Austria), the Alpine region and the Bohemian lands. In the later years of the 19th century, rapid economic growth spread to the central Hungarian plain and to the Carpathian lands. As a result, wide disparities of development existed within the Empire. In general, the western areas became more developed than the eastern.

By the end of the 19th century, economic differences gradually began to even out as economic growth in the eastern parts of the Empire consistently surpassed that in the western. The Empire built up the fourth-largest machine building industry of the world, after the United States, Germany, and Great Britain.[7] Austria-Hungary was also the world's third largest manufacturer and exporter of electric home appliances, electric industrial appliances and facilities for power plants, after the United States and the German Empire.[8][9]

The strong agriculture and food industry of Hungary with its center at Budapest became predominant within the Empire and made up a large proportion of the export to the rest of Europe. Meanwhile, western areas, concentrated mainly around Prague and Vienna, excelled in various manufacturing industries. However, since the turn of the twentieth century, the Austrian half of the Empire could preserve its dominance within the empire in the sectors of the first industrial revolution, but Hungary had a better position in the industries of the second industrial revolution, in these modern sectors of the second industrial revolution the Austrian competition could not become dominant.[10] This division of labour between the east and west, besides the existing economic and monetary union, led to an even more rapid economic growth throughout Austria-Hungary by the early 20th century. The most important trading partner was Germany (1910: 48% of all exports, 39% of all imports), followed by Great Britain (1910: almost 10% of all exports, 8% of all imports). Trade with the geographically neighboring Russia, however, had a relatively low weight (1910: 3% of all exports /mainly machinery for Russia, 7% of all imports /mainly raw materials from Russia). In the Galician north, the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, an ethnic Pole-administered autonomous unit under the Austrian crown, became the major oil-producing region of Europe.[11][12][13][14]

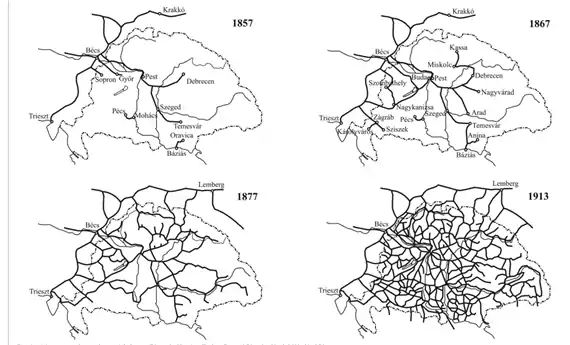

Railways

The Austro-Hungarian Empire realized it needed railways for it had a large population and large territory where travel was difficult. It needed long lines to its coastal ports on the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea. The railway system was built for light duty traffic. The system provided a local demand for iron and steel, coal, rolling stock, terminals, yards, construction projects, skilled workers and manual labor. Although much of the engineering expertise was imported, most of the labor and materials were provided by the empire itself. When Austria and Hungary united in 1867, 6000 km of lines had been built, chiefly in the more industrialized Austria. Quickly all the major cities were linked together by 7600 km of new lines. This promoted rapid industrialization around Vienna, Bohemia, and Silesia. The worldwide economic panic of 1873 ended the construction boom. After 1880 three-fourths of the lines were nationalized. The Orient Express from Vienna to Constantinople was a prestige line, but added little to the economy. After 1900 a new major factor was outward emigration – over 2 million left for the United States in 1900-1914. By 1914 43,280 km were in operation, exceeded in length only by Russia and Germany.[15]

Although of lighter weight and not as well-managed as the German lines, the Austro-Hungarian system played a major role in supporting the Army in the First World War. Half of the rolling stock was reserved for the Army, and the rest was being run down and cannibalized. The system was in virtual collapse by 1918, as the cities ran short of food and coal.[16]

Regions

- Austria: see Rail transport in Austria and Austrian Federal Railways

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: see Rail transport in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Croatia: see Croatian Railways

- Czech Republic: see Rail transport in the Czech Republic and České dráhy

- Hungary: see Hungarian State Railways

- Poland: see Rail transport in Poland and PKP

- Slovakia: see Rail transport in Slovakia

- Slovenia: see Rail transport in Slovenia

References

- "Population of the Major European Countries in millions".

- Martin Moll, "Austria-Hungary" in Christine Rider, ed., Encyclopedia of the Age of the Industrial Revolution 1700–1920 (2007) pp 24-27.

- Millward and Saul, The Development of the Economies of Continental Europe 1850-1914 pp 271–331.

- Good, David. The Economic Rise of the Habsburg Empire

- Stephen Bradberry and Kevin O'Rourke, eds, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe volume 2: 1870 to the present (2010) pp. 34, 61, 65, 75, 76.

- Cambridge economic history of modern Europe 2:8, 12, 22, 36.

- Schulze, Max-Stephan. Engineering and Economic Growth: The Development of Austria-Hungary's Machine-Building Industry in the Late Nineteenth Century, p. 295. Peter Lang (Frankfurt), 1996.

- The Publisher. Vol. 133. 1930. p. 355.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Österreichische konsularische Vertretungsbehörden im Ausland New York (1965). Austrian information. p. 17.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Berend, Iván T. (2013). Case Studies on Modern European Economy: Entrepreneurship, Inventions, and Institutions. Routledge. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-135-91768-5.

- Schatzker, Valerie; Erdheim, Claudia; Sharontitle, Alexander. "Petroleum in Galicia". Drohobycz Administrative District: History. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- Golonka, Jan; Picha, Frank J. (2006). The Carpathians and Their Foreland: Geology and Hydrocarbon Resources. American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG). ISBN 978-0-89181-365-1.

- Frank, Allison (June 29, 2006). "Galician California, Galician Hell: The Peril and Promise of Oil Production in Austria-Hungary". Washington, D.C.: Office of Science and Technology Austria (OSTA). Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- Schwarz, Robert (1930). Petroleum-Vademecum: International Petroleum Tables (VII ed.). Berlin and Vienna: Verlag für Fachliteratur. pp. 4–5.

- Alan Milward, and S. B. Saul, The Development of the Economies of Continental Europe 1850–1914 (1977) pp 302–304.

- Clifford F. Wargelin, "The economic collapse of Austro-Hungarian dualism, 1914-1918." East European Quarterly 34.3 (2000): 263.

Further reading

- Caruana-Galizia, Paul, and Jordi Martí-Henneberg. "European regional railways and real income, 1870–1910: a preliminary report." Scandinavian Economic History Review 61.2 (2013): 167-196. online

- Cipolla, Carlo M., ed. (1973). The Emergence of Industrial Societies vol 4 part 1. Glasgow: Fontana Economic History of Europe. pp. 228–278. online

- Evans, Ifor L. "Economic Aspects of Dualism in Austria-Hungary." Slavonic and East European Review 6.18 (1928): 529-542.

- Good, David. The Economic Rise of the Habsburg Empire (1984) excerpt

- Good, David F. "Austria-Hungary." in Patterns of European Industrialisation: The nineteenth century ed by R. Sylla, and G. Toniolo. (1991): 218-247. excerpt

- Good, D. F. "The Great Depression and Austrian Growth after 1873" Economic History Review (1978) 31: 290–4.

- Good, David F. "The economic lag of central and eastern Europe: income estimates for the Habsburg successor States, 1870-1910." Journal of Economic history (1994): 869-891 online.

- Good, David F. "Uneven development in the nineteenth century: a comparison of the Habsburg Empire and the United States." Journal of Economic History (1986): 137-151 online.

- Grimm, Richard. "The Austro-German Relationship." Journal of European Economic History 21.1 (1992): 111–120, online.

- Katus, L. "Economic growth in Hungary during the age of Dualism (1867-1913): A quantitative analysis" in E. Pamlényi (ed.), Sozialökonomische Forschungen zur Geschichte Ost-Mitteleuropas (1970), pp. 35–127.

- Komlos, John. The Habsburg Monarchy as a Customs Union: Economic Development in Austria-Hungary in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton UP, 1983).

- Milward, Alan, and S. B. Saul. The Development of the Economies of Continental Europe 1850-1914 (1977) pp 271–331. online

- Roman, Eric. Austria-Hungary & the Successor States: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present (2003), 699pp online

- Rudolph, Richard L. Banking and Industrialization in Austria-Hungary: The role of banks in the industrialization of the Czech Crownlands, 1873-1914 (Cambridge UP, 1977). online

- Schulze, Max-Stephan. "Origins of catch-up failure: comparative productivity growth in the Habsburg Empire, 1870–1910." European Review of Economic History 11.2 (2007): 189-218 online.

- Schulze, Max-Stephan. "Austria-Hungary's Economy in World War I." in The Economics of World War I ed. by Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison. (2005) pp 92+.

- Schulze, M.S. "The machine-building industry and Austria's great Depression after 1873" Economic History Review (1997), 50#2 pp. 282–304.

- Turnock, David. The economy of East Central Europe, 1815-1989: stages of transformation in a peripheral region (Routledge, 2004).

- Turnock, David. Eastern Europe: An Historical Geography 1815-1945 (1988) online

- Wargelin, Clifford F. "The economic collapse of Austro-Hungarian dualism, 1914-1918." East European Quarterly 34.3 (2000): 261–280, online.