Economy of the Ethiopian Empire

The economy of the Ethiopian Empire was dominated by the barter system, traditionally composed of Arab and Ethiopian Muslim caravans, and a strong trade culture nourished business within the feudal system. In medieval times, neighboring state Emirate of Harar became the center of commerce while imports and exports passed through the port of Zeila, operated by Muslim merchants, delivering commodities to the Abyssinians through Aliyu Amba a town in Ifat, which connected the Shewa.[1]

Starting during the reign of Menelik II, the Emperor of Ethiopia, modern banking institutions and currencies were introduced, including the Maria Theresa thaler in 1890 and Ethiopia's own currency, minted in Harar beginning in 1892 following the annexation of the Emirate of Harar by the Abyssinians. Despite these changes, the barter system continued into the early 20th century until the Italian occupation in 1936.[2] The first national bank, the Bank of Abyssinia, was established by a fifty-year concession from the National Bank of Egypt in 1905, and had a monopoly on banking. In 1932, by decree of Emperor Haile Selassie, the bank was renamed the Bank of Ethiopia.[3]

After the end of the Italian occupation, the National Economic Council embarked on a state development plan in 1954, led by a policy-making body headed by Emperor Selassie to improve agriculture and industry productivity, literacy and well-being, and the standard of living. The First Five-Year Plan (1957–1961), Second Five-Year Plan (1962–67) and Third Five-Year Plan (1968–73) projected to develop the agricultural industry and manufacturing sector and employ skilled manpower in the country. Between 1960 and 1970, Ethiopia enjoyed an annual 4.4% growth rate in its per capita and overall gross domestic product (GDP). There was an increase in the manufacturing growth rate from 1.9% in 1960–1961 to 4.4% in 1973–74, with the wholesale, retail trade, transportation, and communication sectors increasing from 9.5% to 15.6%.[4]

Feudalism and peasantry

Feudalism was a central tenet in the economy of Ethiopia since the beginning of the imperial regime,[5][6] where peasants were positioned in the lowest level of the social order. Scholars have classified the Ethiopian dominion in terms of the geographical and cultural sphere of the Amhara and Tigre people in the northern provinces of Ethiopia whose conquest was based on freehold patterns of the southern regions. Ethiopian peasants produced and depended on various economic activities such as taxation, marketing infrastructure, and agrarian production. Their dependent households and communities were visible to the wider social system in reciprocity among kinship and associational groupings, and by collection and redistribution of taxes, tribute, and political and religious leaders and marketing goods and services in barter and cash economies.[7][8]

The pioneer of analysis of the premodern economic history of Ethiopia, Richard Pankhurst, published a full-length book titled An Introduction to the Economic History of Ethiopia from Early Times to 1800 in 1961 from available sources published in 1800, which were attributed to Encyclopedia Aethiopica.[9] In 1972, Taddesse Tamrat also contributed to analysis of hagiographies and land charters as well as trade routes and the gult system of land tenure in medieval Ethiopia.[10] Scholars of Ethiopian studies argue that peasants were greatly affected by continual extreme natural and human-made dangers, such as looting, disease and famine, pest infestations, seasonal fluctuations of rivers and streams, and soil erosion in highland areas.[11] During early Ethiopian expansion, highland areas such as Wag and Lasta, and through Shewa across the Great Rift Valley were places of political, cultural and economic agglomeration.[12]

Emirate of Harar

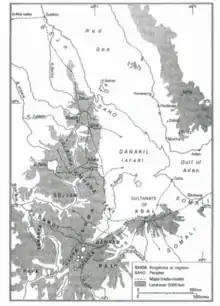

Medieval Emirate of Harar was home to a concentrated bureaucratic commercial system with goods and merchandise imported from and through the Zeila and Barbara routes.[13][1] Zeila was bounded by Somali Eesa territory whereas Barbara ran through the mountains of the Nole tribe.

Most goods were consumed in the Emirate of Harar or sold by Harari merchants sent to Abyssinia, especially to Shewa.. The routes to those provinces linked to the Abyssinian town of Aliyu Amba, connecting them to Harar. Foreign citizens were also involved in local business, mostly Armenians, Greeks, Indians, Syrians, Italians and some Egyptians engaged in selling cotton, cloth, clothing, glassware, brass and copper, drinks and preserves.

Trade items

Principal trading commodities of the empire included coffee, tobacco and sunflower, with 200–300 tons per year. Khat with a market price of a quarter rupees per parcel was another commodity, largely produced or exported to Aden. Locally produced woven clothing, earrings, bracelets, wax, butter, honey, mules, sorghum, wheat karanji (a bread used by travellers), ghee and all kinds of tallow were imported to Harar and exported to other parts of the world. Other monopolized items like ivory, ostrich feathers and musk were also exported.

19th and early 20th century

.jpg.webp)

Trade was carried out using the barter system partly with the aid of commodity money and currency of various kinds. Commerce was traditionally based on two institutions: the local market found in every village (between peasants and local producers) and caravans of Arab and Ethiopian Muslims (typically long-distance trade). The caravans operated in a well-established pattern; large merchants who would make long journeys announced their day of departure. They usually embarked on their journey at dawn and halted for water and pasture.[14]

According to Henry Salt, Tigre people sold wrought iron to make plowshares and other articles, cattle, equines, skins, corn, cotton, butter, onions, and baskets of red peppers. Shops were not available in Adwa and Gondar. Trade routes between Gondar and Massawa were very inconvenient for caravans, often taking five months, while unencumbered travellers sometimes easily undertook for twenty years. Muslims monopolized the trading system in line with an advantage to Christians, controlling most Red Sea and Gulf of Aden ports through Arabia, and in Sudan, trade routes were filled with discrimination wherein merchants were seized as slaves on some occasions.[14]

Menelik II

The economic structure of the Ethiopian Empire was modernized under the reign of Emperor Menelik II, whose power flourished as Negus of Shewa. Several changes occurred, including the introduction of Maria Theresa thalers from Austria in the early twentieth century, the use of Harar currency following the Abyssinian annexation of the Emirate of Harar in 1887, and the minting of coins by the emperor in the 1890s, replacing the barter system. However, resistance emerged from the central and southern provinces.[2]

Bank of Abyssinia concession

By early 1875, Pierre Arnoux advised Menelik II to create Ethiopia's own currency. Around 1900, Frenchman M. Delharbe proposed the first bank, which Menelik rejected due to concerns about French influence. In May 1903, John Lane Harrington, the British plenipotentiary to Ethiopia, supported Menelik's desire and asked him not to reject Whitehall's interest to formulate a proposal. In December 1904, the Foreign Office of Ethiopia approached the governor of the National Bank of Egypt to inquire about undertaking a venture. The bank's governor, Sir Elwin Palmer, replied:[15]

I have the honor to inform you [that] the National Bank of Egypt is prepared to send [a] duly authorized agent to Addis Abbaba [sic] to study the question on the spot, and to negotiate details. Our agent could start as early as Sir J. Harrington, His Majesty's Agent at Addis Abbaba, should think it advisable.

On 10 March 1905, Menelik granted a fifty year concession from the National Bank of Egypt to establish a monopolized bank called the Bank of Abyssinia to lodge all government public funds, issue loans, print banknotes, and mint coins in addition to other privileges. As Menelik's banking request was presented to British authorities in May 1903, France, Britain and Italy, which dominated interests in the Horn of Africa, placed restrictions on Ethiopia's interest while maintaining their own, culminating in the Tripartite Treaty, signed in December 1906.[15]

Britain's undue authority seemed to have appeared in the early stages of the planning, which was supported by economist Gebrehiwot Baykedagn, but Harrington feared the concession would give political weight to the French railway.[15] The bank was established in 1905 with 1 million shillings in capital. According to the agreement, the bank could engage in commercial business (selling shares, accepting deposits, and effecting payments in checks) and issue banknotes. The bank quickly began to expand, opening branches in Harar, Dire Dawa, Gore, and Dembidolo, with agencies in Gambela and a transit office in Djibouti. The bank was later closed by order of Emperor Haile Selassie, who paid compensation to its shareholders, and replaced it with the Bank of Ethiopia in 1932, fully owned by the Ethiopian government, with £750,000 in capital.[3] It was established in accord with the Egyptian concession of 30 May 1905.[16][17]

Haile Selassie

Under Haile Selassie's rule, agriculture was the primary industry in Ethiopia, consisting mostly of coffee production,[18] with a feudal system that relied on inequitable land ownership. The majority of the population was expected to till the fields belonging to wealthy landowners. At this time, industrialization was not fully complete. For instance, the Dutch sugar company HVA, which began operating in Ethiopia in the 1950s, employed 70% of the Ethiopian workforce involved in the food-processing sector; in turn, the food-processing sector employed 37% of the workers in manufacturing and industry.[19]

In 1954–1955, the government created the National Economic Council for state development plans. It was a policy-making body headed by the Emperor to improve agriculture and industry productivity, literacy, well-being, and living standards.[20] The First Five-Year Plan (1957–1961) sought to develop transportation infrastructure, the construction industry, and communication between regions. Another goal was to create a framework of skilled or semiskilled labor in the processing industries to reduce import dependency in Ethiopia. The last goal was to promote agricultural development through commercial ventures.[19][21][22]

The Second Five-Year Plan (1962–1967) envisioned the economy converting to agro-industry, with objectives including diversification over the next twenty years. The Third Five-Year Plan (1968–1973) aimed to facilitate economic well-being by increasing manufacturing and agro-industrial performance. The First Five-Year Plan involved a total investment of about 839.6 million birr, 25% above the projected 674 million birr, the Second Five-Year Plan was 13% higher than planned at 1,694 million birr, and the Third Five-Year Plan was estimated to cost 3,115 million birr. There were numerous issues including deficient national development management that affected the Planning Commission, which prepared the first and second plans, and the Ministry of Planning which planned the third.[19][21]

The project managers failed to achieve the objectives because they did not identify the resources (personnel, equipment, and funds) needed to continue large-scale economic development during the first plan, hampering the growth of the gross national product (GNP). The export rate increased 3.2% annually as opposed to the projected 3.7%, and the growth targets for the agricultural, manufacturing, and mining sectors were also missed. During the first plan, exports reached 3.5% and imports grew by 6.4% per year, continuing a failure to improve the trade deficit that had existed since 1951.[19]

The second and third plans hoped to enrich the economy at the rate of 4.3% and 6.0% respectively, with agriculture, manufacturing and transportation expected to increase at the rates of 2.5%, 27.3% and 6.7% annually in the second plan and 2.9%, 14.9%, and 10.9% in the third. The Planning Commission did not evaluate these two plans as a result of a shortage of qualified personnel. According to the Ethiopian Central Statistical Authority, there was sustainable economic growth in the fiscal years of 1960–1961 and 1973–1974. Between 1960 and 1970, Ethiopia enjoyed an annual 4.4% growth rate in per capita production and gross domestic product (GDP). The manufacturing sector more than doubled from 1.9% in 1960–1961 to 4.4% in 1973–1974, and the growth rate for the wholesale, retail trade, transportation, and communication sectors increased from 9.5% to 15.6%.[19][23]

References

- Caulk, R. A. (1977). "Harär Town and Its Neighbours in the Nineteenth Century". The Journal of African History. 18 (3): 369–386. doi:10.1017/S0021853700027316. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 180638. S2CID 162314806.

- Pankhurst, Alula (2007). "The Logic of Barter in Ethiopian History and its Resilience in Contemporary Society: Case Studies in the Exchange of Food, Clothing and Household Goods". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 40 (1/2): 155–179. ISSN 0304-2243. JSTOR 41988225.

- Teklemedhin, Fasil Alemayehu and Merhatbeb. "The Birth and Development of Banking Services in Ethiopia". www.abyssinialaw.com. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- "Industry and Industrialization in Ethiopia: Policy Dynamics and Spatial Distributions" (PDF). 4 July 2022.

- "The Rise of Feudalism in Ethiopia". Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- Ellis, Gene (1979). "Feudalism in Ethiopia: A Further Comment on Paradigms and Their Use". Northeast African Studies. 1 (3): 91–97. ISSN 0740-9133. JSTOR 43660024.

- Cohen, John M. (1974). "Ethiopia: A Survey on the Existence of a Feudal Peasantry". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 12 (4): 665–672. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00014312. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 159996. S2CID 154715719.

- Cohen, John M. (1974). "Peasants and Feudalism in Africa: The Case of Ethiopia". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 8 (1): 155–157. doi:10.2307/483880. ISSN 0008-3968. JSTOR 483880.

- Scientifique, Secrétaire. "Economic Stagnation in Ethiopia, 1500-1800". UN ŒIL SUR LA CORNE / AN EYE ON THE HORN (in French). Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- Wion, Anaïs (2020-01-08). Medieval Ethiopian Economies: Subsistence, Global Trade and the Administration of Wealth. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-41958-2.

- DECHASA, ABEBE DEMISIE (5 July 2022). "A SOCIO-ECONOMIC HISTORY OF NORTH SHÄWA, ETHIOPIA (1880s-1935)" (PDF). pp. 42, 48.

- Henze, Paul B. (2000), Henze, Paul B. (ed.), "Medieval Ethiopia", Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 44–82, doi:10.1007/978-1-137-11786-1_3, ISBN 978-1-137-11786-1, retrieved 2022-07-05

- Stetler, Susan L. (1993). Cities of the World: A Compilation of Current Information on Cultural, Geographical, and Political Conditions in the Countries and Cities of Six Continents, Based on the Department of State's "Post Reports". Gale. ISBN 978-0-8103-7099-9.

- PANKHURST, RICHARD (1964). "The Trade of Northern Ethiopia in the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 2 (1): 49–159. ISSN 0304-2243. JSTOR 41965707.

- Schaefer, Charles (1992). "The Politics of Banking: The Bank of Abyssinia, 1905-1931". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 25 (2): 361–389. doi:10.2307/219391. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 219391.

- "Banknotes and Banking in Abyssinia and Ethiopia". www.pjsymes.com.au. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- Arnaldo, Mauri (6 July 2022). "The Short Life of the Bank of Ethiopia".

- "Ethiopia - Economy | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- "Ethiopia: Growth and Structure of the Economy ~a HREF="/et_00_00.html#et_03_01"". lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- "Haile Selassie I University - Five Year Plan 1967 - 1971" (PDF). 4 July 2022.

- "An Overview of Ethiopia's Planning Experience" (PDF). 4 July 2022.

- "Development plans - Ethiopia". African Studies Centre Leiden. 2012-08-07. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- "Industry and Industrialization in Ethiopia: Policy Dynamics and Spatial Distributions" (PDF). 4 July 2022.

Further reading

- An Introduction to the Economic History of Ethiopia from Early Times to 1800 by Richard Pankhurst, 1961 ISBN 9781599070810, 1599070812