Economy of the Inca Empire

During the Inca Empire’s comparatively brief reign, from 1438 to 1533, Inca civilization established an economic structure that allowed for substantial agricultural production as well as cross-community exchange of products. Inca society is considered to have had some of the most successful centrally organized economies in history.[1] Its effectiveness was achieved through the successful control of labor and the regulation of tribute resources. In Inca society, collective labor was the cornerstone for economic productivity and the achieving of common prosperity.[2] People in the ayllu (the heart of economic productivity) worked together to produce that prosperity. This prosperity caused the Spanish to be amazed by what they saw when they first encountered the Incas in 1528.[3] According to each ayllu, labor was divided by region, with agriculture centralized in the most productive areas; ceramic production, road construction, textile production, and other skills were also part of the ayllus.[4] After local needs were satisfied, the government gathered all surplus that is gathered from ayllus and allocated it where it was needed. People of the Inca Empire received free clothes, food, health care, and schooling in exchange for their labor.[5]

Ayllus in the Inca Empire

The Incan Empire's economy was based on these ayllus. The ayllus is made up of families who lived in the same village or settlement. People who were born in one ayllu even married within the ayllu, which offered social stability. Depending on its place, each ayllu specialized in the development of appropriate goods. Agricultural ayllus were found near fertile land and grew crops that were suited to the soil type. Their production would be taken by the state, who would then transfer it to other regions of the country where the resource was unavailable. Excess will be kept in storage houses near urban centers, along roads and highways.[6] Other ayllus would specialize in pottery, clothes, or jewelry production; skills were passed on from generation to generation within the same ayllu. Ayllus created almost everything required for daily life, which the state would allocate to other ayllus. The abundance and variety of capital, as well as their availability during bad crops and conflict, rendered people of the Inca empire to be loyal to the Sapa Inca and the local government.[7]

Land possession in the Inca Empire

Individuals as representatives of the ayllu had the freedom to use the property. As the ayllu's delegate, the Kuraka (Quechua for the chief governor of a province or communal authority in the Tawantinsuyu or curaca (Spanish spelling) was an Inca Empire official who served as a magistrate, roughly four ranks below the Sapa Inca, the Empire's head) redistributed the property among the members based on the scale of their communities. The land's measurements were calculated in tupus, a local measuring unit, and differed depending on its agricultural condition. A married pair will get one and a half tupus, with one tupu for each male child and half a tupu for each female child. Each additional tupu was taken away and sent to the new family when the son or daughter began their own family. The property was worked by each family, but they did not own it; the Inca estate was the legitimate owner. The farm was used to supply the family with subsistence food.[8]

Collective labor taxation

The Incas conducted a routine census of the male population to determine if labor conscription was necessary. Individuals, including adolescents, were forced to work in different labor capacities on a revolving basis, whether it was livestock, building, or at home. The government received two-thirds of a farmer's crops (over 20 varieties of corn and 240 varieties of potatoes).[9] The Inca state received its "tax" revenues from such labor. The nation, on the other hand, provided them with housing, food, and clothing in return for their labor. The free allocation of ceremonial beer was one of the special incentives. The Inca bureaucracy used a specific open space in the city's center as a social gathering place for people to celebrate and drink ritual beer[10]

Collective labor may be structured in three ways: The first was the ayni to assist a member of the society in need. Ayni may be shown by assisting with the construction of a house or by assisting a disabled member of the society. The second was the minka, or collective effort for the good of the whole nation. Building farm terraces and washing irrigation canals are two examples of minka. The mita, or tax charged to the Inca, was the third. Mita laborers were warriors, fishermen, messengers, road builders, and whatever else was required. Each participant of the ayllu was expected to fulfill a rotational and temporary service. They constructed temples and palaces, irrigation canals, agricultural terraces, highways, bridges, and tunnels all without the use of a wheel. This structure was a give-and-take system that was well-balanced. The government will have food, clothes, and medicine in return. This scheme required the Inca empire to have all of the requisite produce on hand for redistribution based on need and local interests.[11]

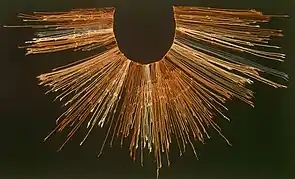

Quipu, record-keeping system

Despite the lack of a written language, the Incas invented a system of record-keeping based on knotted string known as "quipu." To describe the decimal system, these knot structures used complex knot arrangements and color-coded parts. These cords were used to keep track of their stored goods, available workforce, and valuable things such as maize, which was used to craft ceremonial beer.[10] The "quipu" was in control of every economic part of the large empire. "Quipucamayocs" or in other words "Incan accountants" were the ones in charge of keeping the documentation of the quipu.[12] There are 1,500 strings on the biggest quipu. The Sacred City of Caral Supe has the oldest quipu, which dates from about 2500 BC.[13]

Currency in Incan Economy

Money was not used by the Incas.[14] Rather, a person's labor was "rewarded with the guarantee of future mutual assistance and social standing."[14]

Trading system in Inca Empire

A piece of land can be controlled by each seemingly large family. To plow, sow seeds, and later harvest the crops, each required additional labor from the family members. A similar method known as "minka" was used for larger-scale cooperative work, such as the construction of houses or other infrastructure. Participants were compensated in kind. This system is still in use in some Quechua cultures in the Andes. The metaphysical belief principle that underpinned "ayllu" and "minka" was known as "ayni", an ancient Andean idea of mutualism and reciprocity.[2] Because all and everyone in the society was seen as interconnected, each member voluntarily participated in their labor and production. Expecting to be offered something in return later. In a world without monetary currencies, the idea of "ayni" may be applied to all mutual transfers of energy and commodities between people and nature. In addition, the central Inca government instituted supply management and a taxation structure. As a levy, each resident was forced to give the Inca rulers a time of labor and a portion of their cultivated crops. As a result, surplus crops were taken by the government and distributed to villages in desperate need of food.[15]

Infrastructure system of the Inca Empire

The Incas were master builders, constructing a very complex network of roads and bridges of any ancient civilization, known as Qhapaq Ñan. The ability to touch and monitor any corner of their territories contributed to the empire's prosperity. Inca engineers improved upon earlier cultures' highways, such as those built by the Chimu, Wari, and Tiwanaku, among others. In the one of world's most difficult terrains, the Incas constructed more than 18,600 miles/30,000 kilometers of paved roads.[4] Since 1994, UNESCO World Heritage Sites have preserved these roads and all Inca and pre-Inca structures along them. There were two major roads that ran from north to south, one along the coast and the other along the Andes. A smaller network of roads linked the two roads. They constructed a 3,000 m/4,830 km road along the coast that linked the Gulf of Guayaquil in Ecuador to the Maule River in Chile in the south. The Andean royal path, built in the highlands, ran the length of the Andes Mountains. It began in Quito, Ecuador, and ended near Tucuman, Argentina, after passing through Cajamarca and Cusco. The Andean Royal Road was more than 3,500 miles long, far exceeding the length of the longest Roman path.[4] As the Incas had no horses nor wheel technology for much of their history, the majority of traveling was by foot, with llamas transporting merchandise from one section of the empire to the other. Messengers or chasquis used roads to transport messages throughout the empire. The Incas devised strategies for navigating the Andes' rugged terrain. Several paths passed across high mountains. They designed stone steps that looked like massive flights of stairs on steep slopes. Low walls were constructed in desert regions to prevent sand from drifting across the lane.[16]

Bridge building

Bridges were constructed all over the Inca empire, connecting roads that crossed rivers and deep canyons in one of the world's most challenging terrains. The Inca empire's structure and economy necessitated the construction of these bridges. Natural fibers were used by the Incas to build impressive suspension bridges or rope bridges.[17] These fibers were tied together to form a rope that was as long as the bridge's desired length. They braided three of these ropes together to make a stronger, longer rope; they would keep braiding the ropes until they met the required distance, weight, and power. The cables were then bound together with tree branches, and timber was applied to the floor to create a cable floor that was at least four to five feet high. The completed cable floor was then connected to abutments on either side that supported the ends. Ropes that acted as handrails were often fixed on all sides of the bridge. Near Cusco, in the town of Huarochiri, is the only remaining Inca suspension bridge.[18]

Communication in the Inca Empire

Since the Inca Empire ruled over such a large area, they wanted a way to interact with everybody in it. They developed a network of messengers to deliver critical messages. The Chasquis, or messengers, were selected from among the best and fittest male youths. They relayed signals over long distances every day. They stayed in communities of four or six in cabins or tambos along the roads. When one chasqui was seen, another will dash to reach him. He'd sprint alongside the arriving courier, attempting to listen and memorize the message while still relaying the quipu if he had one. The exhausted chasqui would retire to the cabin for rest, while the other would sprint to the next relay stop.[19] Messages could fly over 250 miles a day in this manner. An immediate alert was transmitted via a chain of bonfires in the event of an attack or revolt. When the chasquis saw the smoke, they ignited a bonfire that could be seen from the next cabin or tambo. Before the source of the fire was understood, the Sapa Inca would send his army into the bonfire, where he would normally find a messenger and hear the essence of the emergency from him. Some tambos, or relay sites, were more elaborate than others, according to archeological finds. They were most often used as a rest stop for officials or the Sapa Inca as they traveled through the empire.[20]

References

- D'Altroy, Terence N. (1992). Provincial Power in the Inka Empire. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Morris, Craig; Von Hagan, Andriana (1993). The Inka Empire and Its Andean Origins. New York: Abbeville Press.

- MacQuarrie, Kim (2008). The Last Days of the Incas. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743260503.

- Hyslop, John (1984). The Inka Road System. New York: Academic Press, Inc.

- Davies, Nigel (1995). The Incas. Colorado: University Press of Colorado.

- Levine, Terry (1992). Inka Storage System. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Samuel, Mervyn; Carlessi, Yolanda (2019). Reflections of Peru. Independently Published. ISBN 978-1092301909.

- Hemming, John (1970). The conquest of the Incas. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0156028264.

- Levine, Terry (1985). Inca Administration in the Central Highlands: A Comparative Study. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International.

- Kendall, Ann (1973). Everyday Life of The Incas. New York: B.T. Batsford Ltd.

- Adams, Mark (24 April 2012). Turn Right at Machu Picchu: Rediscovering the Lost City One Step at a Time. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0452297982.

- Bauer, Brian S. (1998). The Sacred Landscape of the Inca: The Cusco Ceque System. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Gerwitz, Ellen (10 January 2013). Honour of Kings Ancient and American History 1 FULL COLOR TEXT. Lulu.com. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-300-62264-2. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Arp, Claire (19 December 2022). "Labor and Power in the Inca Economy". Michigan Journal of Economics. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, María (2001). Pachacutec Inca Yupanqui (in Spanish). Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. pp. 327–328. ISBN 978-9972-51-060-1. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Turolla, Pino (1980). Beyond the Andes: My Search for the Origins of Pre-Inca Civilization. Harpercollins. ISBN 006014369X.

- Ochsendorf, John (1996). An engineering study of the last Inca Suspension Bridge. Princeton university.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dorn, Georgette (8 December 2015). "Engineering in the Andes Mountains: History and Design of Inca Suspension Bridges". Library of Congress.

- Hourly, History (2020). Inca Empire: A History from Beginning to End.

- Rostworowski, Maria; Iceland, Harry B. (1998). History of the Inca Realm. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521637596.