Ed Schieffelin

Edward Lawrence Schieffelin (1847–1897) was an Indian scout and prospector who discovered silver in the Arizona Territory, which led to the founding of Tombstone, Arizona. He entered into a partnership with his brother Al and mining engineer Richard Gird in a handshake deal that produced millions of dollars in wealth for all three men. During the course of Tombstone's mining history, about US $85,000,000 in silver was produced from its mines.

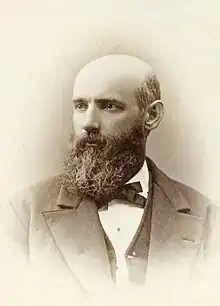

Edward Schieffelin | |

|---|---|

Schieffelin in 1882 | |

| Born | 1847 |

| Died | May 12, 1897 (aged 49–50) |

| Occupation(s) | Indian scout, prospector |

| Known for | Discovery of silver in the Arizona Territory |

| Spouse | Mary Brown |

| Signature | |

Early life

Ed Schieffelin was born in a coal-mining region of Wellsboro, Pennsylvania, the son of a prominent New York and Pennsylvania family, in 1847. His great-grandfather Jacob Schieffelin, Sr., born in 1757, joined the Loyalist army and served as Henry Hamilton's secretary during the Revolutionary War. Schieffelin was captured in 1779 and held prisoner in Williamsburg, Virginia. He escaped to Canada, where in 1780 he was appointed a lieutenant in the Queen's Rangers by Henry Clinton. He spent time in Montreal and Detroit, before returning to New York, where in 1794 he founded a drug company with his brother Lawrence.[1] This firm still exists as a liquor import house, Schieffelin & Somerset. Jacob's wife, Hannah Lawrence, was a descendant of Quaker colonial religious pioneer John Bowne, Elizabeth Fones, and the Winthrop family of New England.

In January 1849, Jacob, Jr. traveled to California with his sons Alfred and Edward Girard on the ship Morrison. They arrived in September, but almost immediately booked passage home via Panama in November.[1] Jacob Schieffelin, Jr. traveled overland and joined his brother and Ed. Schieffelin's father Clinton Emanuel Del Pela Schieffelin settled in the Rogue Valley, Oregon Territory, in the mid-1850s to raise cattle, grain and children. The family maintained an interest in the mining activities in the area.[1][2]

Hunt for gold and silver

At age 17, Schieffelin set out on his own as a prospector and miner. He began looking for gold and silver in about 1865. From Oregon, he went east to Coeur d'Alene, then searched across Nevada into Death Valley, back into Colorado and then New Mexico.[3]

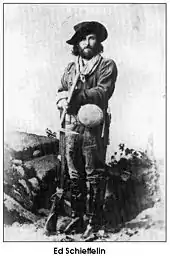

In 1876, David P. Lansing of Phoenix, Arizona, described Schieffelin as "about the strangest specimen of human flesh I ever saw. He was 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m) tall and had black hair that hung several inches below his shoulder and a beard that had not been trimmed or combed for so long a time that it was a mass of unkempt knots and mats. He wore clothing pieced and patched from deerskins, corduroy and flannel, and his hat was originally a slouch hat that had been pieced with rabbit skin until very little of the original felt remained."[2]

A year later as a 30-year-old, Schieffelin moved to California to find gold. He surveyed the Grand Canyon area as well. Unsuccessful, he heard that a group of Hualapai Indians had enlisted as scouts for the U.S. Army, which was establishing a camp to counter the Chiricahua Apache threat and to secure the nearby border with Mexico.[4] The Army established Camp Huachuca at the foot of the Huachuca Mountains in Pima County, Arizona Territory on March 3, 1877. Silver had already been discovered in some northern areas of Arizona Territory, but the southern portion had been under continued Apache attack.

Schieffelin accompanied the scouts on a few trips into the back country while prospecting part-time. He finally decided to stay put and explore the hills east full-time.[4] The hills east of the San Pedro River where he prospected could be dangerous. They were only about 12 miles (19 km) from the hostile Chiricahua Apache Indians led by Cochise, Geronimo and Victorio that had established a stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains.

Ore discovery

Frederick Brunckow, a Prussian-born mining engineer, discovered silver in the hills of Cochise County in 1858. He built a cabin near the San Pedro River after finding a small silver deposit nearby. He hired three other white men and about a dozen Mexican miners. In September 1860, two of the white men were robbed and murdered at the cabin and Brunckow was found dead in the mine with a rock drill through him. The German cook blamed the Mexican workers for the murders. After Brunckow's death, ongoing conflict with native Indians prevented further development of the mines for several years.[5] Brunckow's San Pedro mine influenced Ed Schieffelin to prospect the rocky outcropping northeast of the cabin.[6][7] In 1876, Schieffelin and his party were attacked by Apaches, and a man named Lenox was killed. The cabin was the site of 22 murders during the frontier days.

When friend and fellow army scout Al Sieber learned what Schieffelin was up to, he is quoted as telling him, "The only rock you will find out there will be your own tombstone".[8] Another account reported Schieffelin's friends told him, "Better take your coffin with you; you will find your tombstone there, and nothing else."[9]

In 1877, Schieffelin used Brunckow's cabin as a base of operations to survey the country. After many months, Ed was working the hills east of the San Pedro River when he found pieces of silver ore in a dry wash[10] on a high plateau called Goose Flats.[4] It took him several more months to find the source. When he located the vein, he estimated the vein to be 50 feet (15 m) long and 12 inches (30 cm) wide.[3] Schieffelin's claim was sited near Lenox's grave site, and when he filed his first mining claim on September 21, 1877, he fittingly named his stake "Tombstone".[10][11]

Flat broke, Schieffelin persuaded William Griffith to pay for the legal paperwork required to file a mining claim on September 3, 1877. Tucson did not have an assay office, and when they showed the sample ore to some local men, they thought it was worthless.

With only 30 cents in his pocket, Schieffelin set out to find his brother Al, whom he had not seen in four years. He believed Al was working the Silver King mine, about 180 miles (290 km) to the north in central Arizona Territory near present-day Globe. But Schieffelin learned that Al had moved on to the McCracken Mine in Signal City, Arizona, another 300 miles (480 km) north. Schieffelin spent his 30 cents on tobacco and had to pause in his search for his brother to earn enough money to go on. He found a job as a hoist operator at the Champion silver mine, and for fourteen days hauled up a dozen tons of ore every night by cranking a hand windlass.[10][12]: 14

Partnership formed

When Ed finally located his brother in February 1878, Al asked the foreman at the McCracken mine to look at brother Ed's ore specimens. The foreman thought the samples were mostly lead. Unconvinced, Schieffelin showed the samples to 20 or 30 others who had some expertise, and they all thought the ore worthless. Frustrated, Schieffelin threw his ore specimens out his brother's cabin door, as far as he could throw, but at the last minute held on to three of them.[12]: 15 For the next four weeks he worked in the McCracken Mine, wielding a pick and shovel.

Ed learned about the McCracken Mine's recently arrived assayer, Richard Gird, who had a reputation as an expert. Taking his last three ore samples, Ed Schieffelin asked Gird if he thought they were worth assaying. Gird took a look and said he'd get back to Ed. Three days later, Al shook Ed out of his bunk and said Gird wanted to see him now. When they met, Gird told Ed that he valued the best of the ore samples at $2,000 a ton. Ed, Al Schieffelin and Richard Gird formed a partnership on the spot. Gird offered his expertise, connections, and a grubstake. They shook hands on their three-way deal, a gentlemen's agreement that was never put down on paper but that resulted in millions of dollars of wealth for all three men.[12]: 17 When Richard resigned, his employer offered to make him general superintendent of the mine, but he declined.[12]: 24

Gird bought a second-hand blue spring wagon and loaded it with supplies, his assay equipment, and also bought a second mule that with Ed's mule could haul the wagon. Gird wanted time to wind up his affairs and to wait for spring and better weather, but Ed insisted they depart immediately. Al hesitated to leave his well-paid, $4.00 a day job as a miner. Ed and Gird didn't wait for him, but left that day. Al reconsidered and joined them that night. Reaching Arizona Territory, and despite reports of continued Apache raids and the murder of miners and ranchers in the area, the three men returned to Cochise County and set up camp at the Brunckow cabin. The deaths of several locals at the hands of the Apache Indians were testified to by the fresh graves near the cabin.[13]

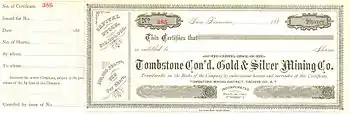

The three partners formed the Tombstone Gold and Silver Mining Company to hold title to their claims.[5] Gird built a crude assay furnace in the cabin's fireplace. He found that Schieffelin's initial find of silver ore was valuable, but within a few weeks of mining the vein, Ed discovered it ended in a pinch about three feet deep.[3][13] His brother Al and Gird were despondent but Ed was optimistic he could find more ore deposits. He continued his search for many more weeks until one day Al found Ed joyously exclaiming over another sample of float ore he had found. Indifferently, Al told Ed he was a "lucky cuss," and that became the name of one of the richest mining claims in the Tombstone District. The ore samples assayed at $15,000 a ton.[12]: 20 Ed shortly afterward identified another claim, the "Tough Nut" lode, rich in horn silver.

On June 17, 1879, Schieffelin showed up in Tucson driving the blue spring wagon carrying the first load of silver bullion valued at $18,744 (about $588,695 today)

Tombstone founded

When the first claims were filed, the initial settlement of tents and cabins was located at Watervale near the Lucky Cuss mine. By March 1879, about 100 residents occupied tents and shacks at Watervale. Former Territorial Governor Anson P.K. Safford offered financial backing for a cut of the men's mining claims, and Ed Schieffelin, his brother Al, and their partner Richard Gird formed the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company and built a stamping mill. On March 5, 1879, U.S. Deputy Mineral Surveyor Solon M. Allis finished laying out a new town site on a mesa named Goose Flats at 4,539 feet (1,383 m), to top of the Tough Nut mine, and large enough to hold a growing town.[14] The town was named "Tombstone" after Schieffelin's initial mining claim. The shelters at Watervale were relocated to the new town site and a scattering of cabins and tents were quickly built for about 100 residents.[14]

During the first few months of mining, the upper portion of the Tombstone mining district was accidentally discovered by Ed Williams and Jack Friday. Late one night, their mules broke loose and dragging their chain, left the miners' dry camp for water along an Indian trail. The men tracked the mules' chain trail all the way to the Schieffelin camp. Williams and Friday noticed a bright gleam where the iron had dragged across bare rock. They filed a claim for their find,[12] but Al and Ed Schieffelin and Richard Gird contested their claim, asserting it violated their earlier claims. When the two parties finally resolved their arguments and counterclaims, they agreed to divide the ground.[15] Williams and Friday took the higher end, which they called the Grand Central, and the Schieffelin company took the lower end, which they named the Contention in remembrance of the quarrel that led to its founding.[12][16] Those two mines were eventually the most profitable mines in Tombstone. Some of the ore from the "Lucky Cuss", "Tough Nut", and the "Contention" mines assayed at around $15,000 to the ton.[10]

Ed Schieffelin preferred prospecting to running a mine and he left Tombstone to find more ore.[15] When he returned four months later, Gird had lined up buyers for their interest in the Contention, which they sold for $10,000 to J.H. White and S. Denson, who represented W.D. Dean of San Francisco. The sellers thought the $10,000 price was exorbitant. The Grand Central and Contention claims turned out to be the richest claims in the district, producing millions of dollars in bullion.[16] The Schieffelin company also soon sold a half-interest in the Lucky Cuss, and the other half turned into a steady stream of money.[16]

On March 13, 1879, Al and Ed Schieffelin sold their two-thirds interest in the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company, which owned the Tough Nut mine, for US$1 million each to the Corbin brothers, Hamilton Distin of Philadelphia, and Simmons Squire of Boston.[17] Safford became president of the new Tombstone Gold and Silver Milling and Mining Company with Richard Gird as superintendent. Ed moved on, but Al remained in Tombstone for some time longer. Gird later sold off his one-third interest for US$1 million, doubling what the Schieffelins had been paid.[12][18] Gird remained in the territory but Ed Schieffelin left to pursue other interests.[12]

When Cochise County was formed in February 1881, Tombstone became the county seat.[19] In 1881, early in Tombstone's rapid growth, Ed's brother Al built Schieffelin Hall as a theater, recital hall, and a meeting place for Tombstone citizens. His great-niece Mary Schieffelin Brady reopened it in 1964[1] and it remains an attraction in Tombstone. It is the largest standing adobe structure in the southwest United States.[20]

At its height in the mid-1880s, Tombstone's population was officially about 7,000 miners, but some estimates figure in an additional 5–7,000 women and children, Chinese, Mexicans, and prostitutes. In the late 1880s, the silver mines reached the water table and the mines eventually filled with water. Tombstone's population faded, until tourism became its main attraction.

Later life

Ed had accumulated more than $1 million in wealth as a result of the silver boom. While he had maintained a casual appearance, including long hair and beard, he cleaned himself up. He traveled to New York City, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and other cities. He met many distinguished people.[12] Ever restless, over the next 20 years Ed showed up at nearly every boom town in the West.

Schieffelin had made a practice of studying maps and believed there was a great "continental belt" of mineral wealth that extended from South America through Mexico, the United States, and British Columbia.[21][22] During 1882, Ed prepared for what he planned to be a three-year survey of mineral wealth. He began the expedition with his brother Al and three others on a trip up the Yukon River. They commissioned construction of and fitted out a small, shallow-draft sternwheel steamer which they named the New Packet.[21] Schieffelin prospected during the trip in Alaska and found some specks of gold. He was for a while convinced he had found the continental belt he had been searching for. But he was extremely discouraged by the Arctic cold he experienced, up to 50 F below zero (-46 C). He decided that mining in Alaska was a lost cause and he returned to the lower 48 states.[22][23]

In 1883, he returned to San Francisco, where he met Mrs. Mary E. Brown. They married the same year in La Junta, Colorado, and they spent part of the winter in Salt Lake City, Utah. In the spring of 1884, they returned to California, where Ed built a mansion for his wife across the bay from San Francisco in Alameda.[12][13] They bought a home in Los Angeles that they shared with Ed's brother Al until Al died of consumption in 1885.

Early death

In 1897 Schieffelin bought a ranch near his brothers Effingham (Eff) and Jacob (Jay) outside Woodville, now Rogue River, Oregon. He continued prospecting in the Canyonville area, where he searched for gold and silver. On May 12, 1897, after he had not shown up in town for supplies for several days, his neighbor checked on him and found him face down on the floor of his miner's cabin.[12]: 24 The coroner ruled that he had died of a heart attack.[13] The ore samples found in his cabin were later reported to have assayed at more than $2,000 to the ton.[10] Other reports from his family said it was only valued at $7 per ton.[2] Schieffelin did not leave a map or directions behind pointing to the origins of his discovery.[10] He was initially buried near his cabin about 20 miles (32 km) east of Canyonville.

It was shortly afterward learned that he had requested to be buried in Tombstone. "It is my wish, if convenient, to be buried in the dress of a prospector, my old pick and canteen with me, on top of the granite hills, about three miles westerly from the City of Tombstone, Arizona, and that a monument, such as prospectors build when locating a mining claim, be built over my grave." Schieffelin was interred about 3 miles (4.8 km) northwest of Tombstone, Arizona, near the dry wash in which he originally found silver ore and the later location of the Grand Central Mine. He was buried as his will specified: in mining clothes, with pick, shovel, and his old canteen.[10] He divided his estate between his wife and his brother Jay. "I give my wife, Mary E. Schieffelin, all interests, both real and personal properties—in Alameda and Santa Clara Counties, California—also fifteen $1,000 University of Arizona Bonds. All other properties, both real and personal, I give to my brother, Jay L. Schieffelin."[13] Mary Schieffelin moved to New York City after her husband's death.[22][24]

Legacy

A 25 feet (7.6 m) tall monument representing the type of marker a miner makes in claiming a strike was erected near the spot of his original claim.[10] The plaque on it reads, "Ed Shieffelin, died May 12, 1897, aged 49 years, 8 months. A dutiful son, a faithful husband, a kind brother, and a true friend."[13] Years before, Schieffelin had written, "I never wanted to be rich, I just wanted to get close to the earth and see mother nature's gold."[2] Schieffelin Gulch Road in the Rogue Valley, Oregon is named after the family who homesteaded there.[2]

There are widely varying estimates of the value of gold and silver mined during the course of Tombstone's history. In 1883, writer Patrick Hamilton estimated that during the first four years of activity the mines produced about $25,000,000 (approximately $785 million today). Other estimates include $40 million[4] to $85 million[13] (about $1.3 billion to $2.77 billion today). Renewed mining is planned for the area.[25]

References

- "The Schieffelin Family". New Haven, CT: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- Brown, Ron (September 10, 2010). "Oregon Trails: The story of Ed Schieffelin and Tombstone". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Moore, Richard E. (Winter 1986). "The Silver King: Ed Schieffelin, Prospector". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 87 (4): 367–387. JSTOR 20614087.

- "Silver in the Tombstone Hills". Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- "Mining History". Tombstone Exploration Corporation. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- Koch, Eckehard. "den Roten gehörte alles Land; es ist ihnen von uns genommen worden". Jahrbuchder Karl-May-Gesellschaft (Yearbook of the Karl May Society) (in German). Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "Ghost Towns". Discover Southeast Arizona. Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Beebe, Lucius Morris; Clegg, Charles (1955). The American West: the Pictorial Epic of a Continent. Dutton.

"Whar you goin', Ed?" Al Sieber asked his friend who was saddling a mule, one day in 1877. "Just out a ways, looking for stones," Ed Schieffelin replied. "Don't you know this country's full of Indians? Only stone you'll find will be your tombstone." But Ed rode out, alone. Next day his mule suddenly shied at something white. Ed dismounted. There on the hillside lay the skeletons of two men! Moreover, their outstretched arms touched a pile of silver nuggets. Excitedly Ed looked around, found the source of the ore, then rushed home to file his claim. In a few months he was a millionaire and a city of 15,000 people had sprung up there, wildest, toughest boom town in Western history. Its name? Remembering his friend's prophesy, Ed Schieffelin grinned to himself on that discovery day and said: "I'll name this place Tombstone." Thus Tombstone, Arizona, and its newspaper The Epitaph, have become famous the world 'round.

- Bishop, William Henry (1900). Mexico, California and Arizona. New York and London: Harper and Brothers. p. 468. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Hendricks, Janice. "Thirty Cents and a Hunch". Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Horn p. 26, 27

- Walter Noble Burns (1 September 1999). Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest. UNM Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-8263-2154-1. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "The Story of Edward Schieffelin". March 24, 2008. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "Solon Allis". The Mineralogical Record. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- Trimble, Marshall (1986). Roadside History of Arizona. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-87842-197-1.

- "Tombstone's Riches". Legends of America. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- "Tombstone's Riches". Legends of America. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form". United States Department of the Interior National Park Service. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- "Our Little Corner of Cochise County" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-07. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- "A Brief History of Tombstone". Goose Flats Graphics. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- "To Search for Gold in Alaska". New York Times. May 28, 1882. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- Berton, P., (1958). The Klo(=)dike Fever. Alfred A Knopf: New York, pp. 11–12.

- "The Schieffelin Brothers Yukon River Prospecting Trip of 1882". New York Times. April 3, 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "New York Mothers Club". New York Times. May 15, 1900. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "Tombstone Mining". Retrieved 3 May 2011.

Further reading

- Craig, R. Bruce, editor. Portrait of a Prospector: Edward Schieffelin's Own Story. (2017) Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-5773-3

![]() Media related to Ed Schieffelin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ed Schieffelin at Wikimedia Commons