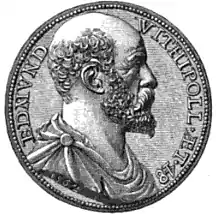

Edmund Withypoll

Edmund Withypoll (1510/13 – 18 May 1582), Esquire,[2] of London, of Walthamstow, Essex, and of Ipswich, Suffolk, was an English merchant, money-lender, landowner, sheriff and politician, who established his family in his mother's native county of Suffolk,[3] and built Christchurch Mansion, a distinguished surviving Tudor house, as his Ipswich home.[4]

Background and origins

Edmund Withypoll was a son of the Merchant Taylor and Merchant Adventurer Paul Withypoll and his wife Anne, daughter of Robert Curson of Brightwell, Suffolk,[5] whose cousin Sir Robert, Lord Curson, Papal Count, had a large double-courtyard mansion in Silent Street, Ipswich.[6] Of a family of Shropshire origins, Paul Withypoll's father John, in partnership with the Thorne and Forster families, and they with George Monoux[7] of Walthamstow, conducted substantial trade operations with Spain and Portugal out of Bristol.[8] Paul married in 1510, from which time he became settled in London, where Edmund and his brothers and sister Elizabeth were presumably born. Monoux was Sheriff of London in 1509–10 and Lord Mayor in 1514–15. The Thorne and Withypoll families were conspicuous collectors of precious objects:[9] the Withypool Triptych, completed in 1514, survives as testimony of Paul Withypoll's patronage.[10]

Paul Withypoll and the Thornes (one of whom, Robert the younger, married Paul's sister) maintained their association in London, and, from the later 1520s, in Walthamstow, where Withypoll became established.[11] Active as assistant to the Merchant Adventurers,[12] Paul was named for an alderman in 1527 but successfully made suit to be discharged.[13] He rose to be M.P. for the City of London in 1529–35, Master of the Merchant Taylors (1537/8) and again M.P. in 1545. In consideration of his great sagacity and discretion, in 1539 he received the honour (unique for a person unqualified) to be present at all Common Councils of the city and at the elections of the Mayors and Sheriffs.[14] His daughter Elizabeth, who died in 1537, became Elizabeth Lucar, the very accomplished wife of Emanuel Lucar, an esteemed Merchant Taylor. Lucar lived to 1573: having been imprisoned and fined by Queen Mary for his part in the acquittal of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton in 1554, he became Master of the Company in 1560,[15] and was a contributor to the foundation of the Merchant Taylors' School.[16]

Career

Edmund was educated by the humanist scholar Thomas Lupset, who taught him Latin, and who in 1529 (while staying at Wolsey's palace at The More, Hertfordshire) wrote in the form of a letter dedicated to Withypoll An Exhortation to Yonge Men (published 1535).[17][18] This remarkable text gives many insights into the character of the young man.[19][20]

In around 1535 Edmund married Elizabeth, youngest daughter of Thomas Hynde, prominent Mercer[21] and Merchant Adventurer of London, and his wife Margaret (daughter of the Mercer William Browne, Lord Mayor of London 1507–08[22]): Hynde, who died in 1529, had provided for a dowry of 200 marks for his daughter.[23] The eldest son and heir, Paul Withypoll, was born around 1536, and others followed in close succession.

In 1540 Edmund purchased lands at Withypole, Shropshire, from his uncle John Withypoll. In 1544 he apparently accompanied the King's expedition at Boulogne: a beautiful manuscript folio of the Letters of Cicero, now in Canterbury Cathedral Library, carries his inscription noting that he took it from the Church of Our Lady at "Bulleyn" in September of that year.[24] With his father, in 1544 Edmund purchased the fee of the manor of Mark at Walthamstow, and briefly held that of Walthamstow Tony.[25]

In the following year father and son together purchased the manor of Christchurch at Ipswich, including the site and the possessions of the dissolved Priory of the Holy Trinity, Ipswich. Upon Paul's death in 1547 (he was buried in St Lawrence Pountney), Edmund succeeded as heir and began the building of "Withipoll Howse" (as he named it in his will of 1582[26]), the building now known as "Christchurch Mansion". The date 1549 appears on a stone bearing a Latin motto above the porch of the Mansion. The adjacent church of St Margaret's, Ipswich, soon became the family's habitual place of baptism, marriage and burial, commencing with his son Peter, who was baptised there on 20 March 1549.[27]

Withypoll soon ran into difficulties over his development. He was alleged to have demolished a priest's house and a churchyard wall, to have plundered materials from a church window, and to have denied access to the churchyard, and was ordered to pay arrears owing to parishioners.[28] Edmund is described as "gent., of Gwipiswiche" in deeds of 1554 granting the rental of his properties of the Bear and the Dolphin Taverns, in Southwark.[29] He was elected a member of parliament (MP) for Ipswich in 1558. He sat on the bench as a Justice of the Peace for Suffolk from 1561 to his death and was appointed High Sheriff of Suffolk for 1570–71.

In 1567 Withypoll confronted the Town Bailiffs[30] over their attendance at the "Holy Trinity Fair" (granted to the Priory by Henry II) held annually in Tuddenham Road beside Christchurch. He objected that it had been customary to lodge the town's ceremonial maces with the Priory for the fair's duration, which in default of their having done, he advised them not to attend. The Councilmen instructed the Bailiffs (as Clerks of the Market, and Justices of the Peace) to disregard his message, and Withypoll blocked various highways and opposed their entry. He brought a suit in Star Chamber, which the Bailiffs and Commonalty resolved to defend and oppose fully, at the town's expense. Loans were sought from the Portmen, councilmen and burgesses, and scot and lot was imposed upon the householders to raise £200 for the town's debts and for this suit, upon pain of distraint, seizure of property, disfranchisement and imprisonment for default of payment.[31][32]

Full records of the affair were preserved by the Borough, which brought counter-suits claiming that Withypoll had illegally enclosed lands, highways, conduits and other amenities, and had committed various other infringements of rights.[33] Conversely, at his manorial Courts Baron held at much the same time, Withipoll had difficulties in obtaining due payment of fines and adequate repairs to properties: in taking control he incurred at least one suit in Chancery which was not resolved until 1579. There is a note of exasperation in Withypoll's rejoinder:

"As towchinge John Dameron one of the said complainauntes ... he neded no answere, sithence the said complainaunte by his owne bill had confessed that he had no title, And therefore mighte very well have spared the vayne blottinge of so muche paper yf he delited not to have his name contempteously sounde in sutes of lawe"[34]

Literary connections

Edmund's sons Daniel and Bartholomew, who pre-deceased him, were linked with George Gascoigne in a skittish poem of Gabriel Harvey's.[35] Bartholomew ('Bat') was an intimate friend of Gascoigne's, as the 1572 verses "Counsell to Bartholomew Wythipole" reveal.[36] Edmund's own literary interests are shown in extracts included in essays by Harvey, including these lines translated by Edmund from a Latin epigram dedicated to Thomas Seckford:[37]

"Our merry dayes, by theevish bit are pluckt, and torne away,

And every lustie growing thing, in short time doth decay,

The pleasaunt Spring times ioy, how soone it groweth olde?

And wealth that gotten is with care, doth noy as much be bolde,

No wisedome had with Travaile great, is for to trust indeede,

For great mens state we see decay, and fall downe like a weede.

Thus by degree we fleete, and sink in worldly things full faste,

But Vertues sweete and due rewardes stande sure in every blaste."[38]

Death and legacy

Withypoll died in May 1582 and was buried, according to his instructions, in St Margaret's, Ipswich. By his earlier, shorter will of 1568[39] he made arrangements for legacies of money deposited in the Bank of Genoa. By his will of 1582 Edmund Withipoll left substantial estates in the hands of his feoffees, Sir Thomas Cornwallis of Brome, Thomas Lucas, M.P., of Colchester,[40] Edward Grimston of Rishangles and John Southwell.

The principal estate consisted of the manor and house of Ipswich Withipoll, with the rectory of Tuddenham St Martin and the chapel of Cauldwell, with appurtenances in Ipswich, Westerfield, Tuddenham, Bramford, Thurleston and Whitton, and also the manor of Rise Hall, with appurtenances in Akenham, Whitton, Thurleston, Blakenham on the water, Westerfield and Claydon, and all his other lands in those parishes and in Rushmere St Andrew, Barham, Chelmondiston, Holbrook, Shotley, Woolverstone and Stutton; also the manors of Westerkell and Kellcottes in Lincolnshire, with their possessions in Esterkell, Larthorpe, Slickforth and Stickney, and the Lordship of the manor of Le Mark in Essex with its possessions in Walthamstow and Leyton, including the rectory and advowson of Walthamstow parish church. All this was bequeathed to his grandson Paul, with reversion in default of male issue to Paul's brother Edmund, and so in succession to the younger sons of the testator.[41]

Possessions in Bildeston, Hitcham and Kettlebaston were left to his son Edward, and to Ambrose his manor of Wheelers at Frating in Essex, with appurtenances in Thorington and Bentley.[42] With regard to his widow, he wrote: "I leave to my wife Elizabeth, for her dower, all my lands in Walthamstow and Leyton, during her life, which is within little of 200 marks by the year: trusting (yea, I may say, as I think, assuring myself), that she will marry no man, for fear to meet so evil a husband as I have been."[43] Elizabeth survived him by two years.

Family

He married Elizabeth, daughter of Thomas Hynde, a London merchant. They had eleven sons and seven daughters.[44]

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_917426.jpg.webp)

Sons (listed by Hervey):

- Powle Withypoll (c. 1536–1579), son and heir, matriculated pensioner from Gonville Hall, University of Cambridge, Easter 1554. Admitted at Gray's Inn, 1555. Paul Withypoll Esquire of Rendlesham, Suffolk, married Dorothy, a daughter of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Baron Wentworth, and had two sons and two daughters. He was buried at St. Margaret's church, Ipswich on 10 December 1579:[45] Dorothy later remarried to Sir Martin Frobisher. Paul having died before his father Edmund, his son Paul succeeded as heir upon Edmund's death. The younger Paul died without issue in 1585,[46] when the principal estates reverted to his brother Edmund under the terms of their father's will. This younger Edmund, protagonist in a notable dispute with Anthony Felton,[47] was knighted in 1601 and died in 1619.

- John Withypoll

- Bartholomew Withypoll (c. 1539–1573), matriculated pensioner from Gonville Hall, University of Cambridge, Easter 1554.[48] A friend of the poet Gascoigne. In 1562 he was in Madrid as the servant of Thomas Chaloner.[49] He died in 1573 following a journey to Genoa to collect his inheritance.[50]

- Edward Withypoll (c. 1540-after 1595), matriculated pensioner from Gonville Hall, University of Cambridge, Easter 1554. Admitted at Gray's Inn in 1553. He married (c.1578) Elizabeth, daughter of Sir John Brewsse, of Little Wenham, Suffolk.[48] He was named an Executor of his father's will of 1582, but reserved his powers, leaving his brother Peter to act alone. Edward and Elizabeth, and their children John, Edward, Philip and Cecily, were all living in 1595/6.[51]

- Daniel Withypoll (c. 1541-before 1577), matriculated pensioner from Gonville Hall, University of Cambridge, Easter 1554. Took B.A. in 1559/60 and M.A. in 1563, becoming a Fellow of St John's College in 1560. He left no issue.[48]

- Jeremy Withypoll

- William Withypoll

- Peter Withypoll (1549–1613), was probably the first to be christened at St. Margaret's in Ipswich. He matriculated from Magdalene College, Cambridge in 1564 and, having been admitted Fellow of Trinity Hall in 1572 soon afterwards graduated LL.B. Progressing to a Doctorate of Laws, he became a skilled lawyer. He resigned his fellowship around 1583, he married Thomasin, daughter of Thomas Cobb, and widow of John Howe jnr. of Stowmarket, where he afterwards lived. He was Commissary to the Bishop of Norwich for the Archdeaconry of Suffolk from 1580 to 1586.[52] The acting Executor of his father's will in 1582, Peter Withypoll defended a challenge (probably relating to the inheritance money banked in Genoa) brought by his nephew Sir Edmund in 1606 on the basis of a will of his father's written in 1568.[53]

- Ambrose Withypoll (1551–1585), married Martha, daughter of Richard Denny of Bawdsey.[54]

- Benedyke Withypoll

- Benjamin Withypoll (1557–1598), matriculated pensioner of Trinity College, Cambridge in 1575. His wife Margaret died in Ipswich in 1591.[55]

Daughters (listed by Hervey):

- Anne Withypoll

- Alice Withypoll

- Anne Withypoll, married Robert King, Portman of Ipswich, in 1573.[55]

- Marye Withypoll, married Robert Wulmerston (or Wolverston) in 1572. They had sons Robert, Edmund and Charles and daughter Mary.[55]

- Martha Withypoll (b. 1550), married Edward Newman of Brightwell, at Acton, in 1579.[56]

- Elizabeth Withypoll (1553–?1592), married (1) (as his third wife) Henry Reynolds or Rendles of Little Belstead, who died c. 1587. She married (2) (as his second wife) George Brooke of Aspall, and they had two sons.[56] It has been suggested that Elizabeth was the mother of the poet Henry Reynolds,[57] who wrote the English translation of Tasso's Aminta (1628),[58] and Mythomystes (1632).[59]

- Frances Withypoll, married Thomas Blague of Sudbury in 1587.[56]

References

- E. Hawkins (ed. A.W. Franks and H.A. Grueber), Medallic illustrations of the History of Great Britain and Ireland to the Death of George II, Vol. I (The British Museum, 1885).

- Contrary to many accounts, Edmund Withipoll never received knighthood, and styled himself 'Esquier' in his will of 1582. "Sir" Edmund Withipoll was his grandson and eventual heir.

- A.D.K. Hawkyard, 'Withypoll, Edmund (1510/13-82), of London; Walthamstow, Essex and Christchurch, Ipswich, Suff.', in S.T. Bindoff (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558 (Boydell & Brewer 1982), History of Parliament online.

- G.C. Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll: with special reference to the Manor of Christchurch, Ipswich, revised with additions by P.H. Reaney, Walthamstow Antiquarian Society official publication no. 34 (1936).

- H. Miller, 'Withypoll, Paul (by 1485–1547), of London and Walthamstow, Essex,', in S.T. Bindoff (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558 (Boydell and Brewer, 1982). History of Parliament Online.

- Robert Curson of Brightwell was son of William (see T.N.A. Discovery Catalogue, item HD 1538/253/115 (Suffolk Record Office, Ipswich), 1468); Sir Robert is supposed son of Robert Curson of Blaxhall. J.M. Blatchly and B. Haward, 'Sir Robert, Lord Curson, soldier, courtier and spy, and his Ipswich mansion,' Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History XLI Part 3 (2007), pp. 335–49; also J.M. Blatchly, 'Curson, Sir Robert (c. 1460–1534/5), soldier and courtier', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- H. Miller, 'Monoux, George (by 1465–1544), of Bristol, Glos.; London and Walthamstow, Essex', in S.T. Bindoff (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558 (Boydell & Brewer 1982). History of Parliament online.

- R.C.D. Baldwin, 'Thorne, Robert, the elder (c. 1460–1519), also including Robert Thorne the younger (1490–1532) and Nicholas Thorne (1496–1546)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- H. Dalton, Merchants and Explorers: Roger Barlow, Sebastian Cabot, and Networks of Atlantic Exchange 1500–1560 (Oxford University Press 2016); forthcoming, H. Dalton, 'Portraits, pearls, and things "wch are very straunge to owres": The Lost Collections of the Thorne/Withypoll Trading Syndicate, 1520–1550', in C.M. Anderson (ed.), Early Modern Merchants as Collectors (Routledge, London and New York, 2016). See Conference Abstracts, Ashmolean Museum, 15–16 June 2012, pp. 2–3. Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery accession K 1394; the side panels, which include the Withypoll arms, are in collections of the National Gallery, accessions NG 646 and 647. See National Inventory of Continental European Paintings. Images: Photo by Lisa Radley in flickr.com. Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, p. 18.

- L. Lyell and F.D. Watney (eds), Acts of Court of the Mercers' Company 1453–1527 (Cambridge University Press 1936), p. 477-78 and passim.

- See Petition of 14 February 1535 for diminution of the expenses of the shrievalty, in J. Gairdner (ed.), Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII Vol. 8, January–July 1535 (H.M.S.O., London 1885), p. 78, item 208. (British History Online. Retrieved 19 January 2017).

- W. Maitland, The History and Survey of London from its Foundation to the Present Time, 2 vols (By Authority, T. Osborne, J. Shipton and J. Hodges, London 1756), I, p. 236, col. 2.

- An account of Emanuel Lucar will be found in C.A. Bradford, 'Emanuel Lucar and St. Sepulchre, London', Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society New Series VIII Part 1 (Bishopsgate Institute, London 1938), pp. 14–30, (pdf pp. 100–116). Pedigree in Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, p. 36.

- C.M. Clode, The Early History of the Guild of Merchant Taylors, II: The Lives (Harrison and Sons, London 1888), p. 159.

- Miller, 'Withypoll, Paul', History of Parliament online.

- Thomas Lupset, An Exhortation to yonge men, perswadinge them to walke in the pathe way that leadeth to honeste and goodnes. Written to a frend of his by T. Lupsete, Londoner. B.L. (T. Berthelet, Londini 1535). See Bonhams, Sale 1 April 2008 (Book Collection of John and Monica Lawson), Lot 565.

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, pp. 40–42.

- Text in E.M. Nugent, The Thought and Culture of the English Renaissance. An Anthology of Tudor Prose, 1481–1555 (Cambridge University Press, 1956), pp. 82-88 (Google).

- Hynde was Warden of the Mercers in 1513/4 and 1523/4, see Lyell and Watney, Acts of Court of the Mercers' Company, passim.

- A.B. Beavan, The Aldermen of the City of London Temp. Henry III to 1912 (Corporation of the City of London, 1913), II, p. 20. Some relationships described in this work are unreliable.

- Will of Thomas Hynde, Mercer of London (P.C.C. 1529).

- (W. Clarke), Repertorium Bibliographicum: or, Some Account of the Most Celebrated British Libraries, Vol. I (William Clarke, London 1819), p. 125.

- 'Walthamstow: Manors', in W.R. Powell (ed.), A History of the County of Essex, Vol. 6 (V.C.H., London 1973), pp. 253–63 (British History Online. Retrieved 14 April 2017).

- Will of Edmund Withipoll, written 1.v.1582 (P.C.C. 1582).

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, p. 45.

- D.H. Allen, Ipswich Borough Archives, 1255–1835: A Catalogue, Suffolk Records Society XLIII (Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2000), p. 14, item C/1/6/3.

- 'VI: Abstract of sundry deeds relating to houses in the parishes of St. Saviour and St. Olave' (etc), Collectanea Topographica et Genealogica V (J.B. Nichols and Sons, London 1838), p. 45ff, nos. 2, 3 & 4..

- Under King John's Charter of 1200, the Borough of Ipswich elected two Bailiffs and twelve Portmen to lead its Council assembly. R. Malster, A History of Ipswich (Phillimore & Co. Ltd., Chichester 2000), pp. 20–21, and p. 68.

- W.H. Richardson (ed.), The Annalls of Ipswche. The Lawes, Customes and Governmt of the Same. Collected... by Nathll Bacon (S.H. Cowell, Ipswich 1884), pp. 277–81.

- The National Archives, Discovery Catalogue, items STAC 5/W9/38; STAC 5/W11/10; STAC 5/W26/40; STAC 2/20/178.

- Allen, Ipswich Borough Archives, pp. 14–17, items C/1/6/4, C/1/6/5 and C/1/6/6.

- The National Archives, Chancery Final Decrees, Dameron v Withipoll (29 October 1579), ref. C 78/51/23. (R. Palmer, Anglo-American Legal Tradition images 0069-0073, at Image 0071. (University of Houston/O'Quinn Law Library)).

- E.J.L. Scott (ed.), Letter-Book of Gabriel Harvey, AD 1573–1580, Camden Society New Series XXXIII (1884), pp. 56–8.

- G. Gascoigne, A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres bounde up in one small Poesie (Richard Smith, London 1573): see A. Chalmers, The Works of the English Poets, from Chaucer to Cowper, 21 vols., Vol. II (J. Johnson, etc. London 1810), p. 451 and pp. 533–34.

- Seckford was M.P. for Ipswich, and his "Great Place" there, in Westgate Street, stood a short distance from Christchurch Mansion. See 'Seckford, Thomas I (1515 or 1516–87), of Woodbridge and Ipswich, Suff. and Clerkenwell, London,' in S.T. Bindoff (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558–1603 (Boydell and Brewer 1982), History of Parliament Online.

- See Two other, very commendable letters, following Three Proper and Wittie, Familiar Letters (H. Bynneman, London 1580), reproduced in J. Haslewood (ed.), Ancient Critical Essays upon English Poets and Poesy (Robert Triphook, London 1815), II, pp. 255–303, at pp. 302–03.

- The 1568 will transcribed in the P.C.C. register for 1606 is considerably shorter than that of 1582 – but may be only an extract?

- 'Lucas, Thomas (1530/1-1611) of the Inner Temple, London, and Colchester, Essex', in S.T. Bindoff (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558 (Boydell and Brewer 1982).History of Parliament online.

- Inquisition post mortem of Edmund Withipole (1582), The National Archives ref. C 142/197/78.

- Will of Edmund Withipoll (P.C.C. 1582).

- D. Lysons, 'Walthamstow: Rectory, etc.', in The Environs of London, Vol.4: Counties of Herts, Essex and Kent (T. Cadell and W. Davies, London 1796), p. 219, at note 90 (Internet Archive).

- 'Wythipool of Ipswich', in Hervey (Clarenceux King of Arms) Suffolk 1561 Heraldic Visitation, see W.C. Metcalfe, The Visitations of Suffolk 1561, 1577, 1612 (Private, Exeter 1882), p. 82.

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, p. 55. Given as '9 December 1577' by J. Venn & J.A. Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses I.iv, Saal to Zuinglius (Cambridge University Press 1927), pp. 484–85 (as "Wythypoll"). See also J. Venn, Biographical History of Gonville and Caius College, 1349–1897, I: 1349–1713 (Cambridge University Press 1897), p. 37.

- Will of Paul Withypoll (P.C.C. 1585).

- A. Hervey, 'Playford and the Feltons', Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History IV, Part 4 (1870), pp. 16-64, at pp. 31-32. Suffolk Institute pdf.

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses I.iv.

- J. Stevenson (ed.), Calendar of State Papers, Foreign Series, of the Reign of Elizabeth, 1562 (Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer, London 1867), p. 214, no. 432, pp. 258–59, nos. 514, 520.

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, pp. 55–58.

- Will of Gyles Bruse (P.C.C. 1595/6): see F.A. Crisp, 'Little Wenham, Co. Suffolk', Fragmenta Genealogica VIII (Frederick Arthur Crisp 1908), at p. 34.

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, pp. 60–62.

- First will of Edmund Withypoll, written 6.iv.1568, and Sentence relating (P.C.C. 1606).

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, p. 62.

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, p. 63.

- Moore Smith, The Family of Withypoll, p. 64.

- K. Tillotson and B.H. Newdigate (eds), The Works of Michael Drayton edited by J. William Hebel, Vol. 5 (Basil Blackwell, 1931), p. 216.

- H. Reynolds, Torquato Tassos Aminta Englisht. To this is added Ariadne's complaint in imitation of Anguillara ; written by the translator of Tasso's Aminta (Aug: Mathewes for William Lee, at the signe of the Turkes Head in Fleetstreet, London 1628)

- H. Reynolds, Mythomystes: wherein a short suruay is taken of the nature and value of true poesy and depth of the ancients above our moderne poets. To which is annexed the tale of Narcissus briefly mythologized (Printed by George Purslowe for Henry Seyle, at the Tigers-head in St. Pauls Church-yard, London 1632).

.