Eadred

Eadred (c. 923 – 23 November 955) was King of the English from 26 May 946 until his death. He was the younger son of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu, and a grandson of Alfred the Great. His elder brother, Edmund, was killed trying to protect his seneschal from an attack by a violent thief. Edmund's two sons, Eadwig and Edgar, were then young children, so Eadred became king. He suffered from ill health in the last years of his life and he died at the age of a little over thirty, having never married. He was succeeded successively by his nephews, Eadwig and Edgar.

| Eadred | |

|---|---|

Eadred in the early fourteenth-century Genealogical Roll of the Kings of England | |

| King of the English | |

| Reign | 26 May 946 – 23 November 955 |

| Coronation | 16 August 946 Kingston upon Thames |

| Predecessor | Edmund I |

| Successor | Eadwig |

| Born | c. 923 Wessex |

| Died | 23 November 955 (aged c. 32) Frome, Somerset |

| Burial | Old Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Edward the Elder |

| Mother | Eadgifu |

Eadred's elder half-brother Æthelstan inherited the kingship of England south of the Humber in 924, and conquered the south Northumbrian Viking kingdom of York in 927. Edmund and Eadred both inherited kingship of the whole kingdom, lost it shortly afterwards when York accepted Viking kings, and recovered it by the end of their reigns. In 954 the York magnates expelled their last king, Erik Bloodaxe, and Eadred appointed Osullf, the Anglo-Saxon ruler of the north Northumbrian territory of Bamburgh, as the first ealdorman of the whole of Northumbria.

Eadred had been very close to Edmund and inherited many of his leading advisers, such as his mother Eadgifu, Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Æthelstan, ealdorman of East Anglia, who was so powerful that he was known as the 'Half-King'. Dunstan, Abbot of Glastonbury and future Archbishop of Canterbury, was a close friend and adviser, and Eadred appears to have authorised Dunstan to draft charters when he became too ill to attend meetings of the witan (King's Council) in his last years.

The English Benedictine Reform did not reach fruition until the reign of Edgar, but Eadred was a strong supporter in its early stages. He was close to two of its leaders, Æthelwold, whom he appointed Abbot of Abingdon, and Dunstan. However, like earlier kings he did not share the view of the circle around Æthelwold that Benedictine monasticism was the only worthwhile religious life and he appointed Ælfsige, a married man with a son, as Bishop of Winchester.

Background

In the ninth century the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia came under increasing attack from Viking raids, culminating in invasion by the Danish Viking Great Heathen Army in 865. By 878, they had overrun East Anglia, Northumbria, and Mercia, and nearly conquered Wessex, but in that year the West Saxons fought back under Alfred the Great and achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington. In the 880s and 890s the Anglo-Saxons ruled Wessex and western Mercia, but the rest of England was under Viking rule. Alfred constructed a network of burhs (fortified sites), and these helped him to frustrate renewed Viking attacks in the 890s with the assistance of his son-in-law, Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, and his elder son Edward, who became king when Alfred died in 899.[1] In 909, Edward sent a force of West Saxons and Mercians to attack the Northumbrian Danes and the following year the Vikings retaliated with a raid on Mercia. While they were marching back to Northumbria, they were caught by an Anglo-Saxon army and decisively defeated at the Battle of Tettenhall, ending the threat from the Northumbrian Vikings for a generation. In the 910s Edward and Æthelflæd – his sister and Æthelred's widow – extended Alfred's network of fortresses and conquered Viking-ruled eastern Mercia and East Anglia. When Edward died in 924, he controlled all England south of the Humber.[2]

Edward was succeeded by his eldest son Æthelstan, who seized control of Northumbria in 927, thus becoming the first king of all England. Soon afterwards Welsh kings and the kings of Scotland and Strathclyde acknowledged his overlordship. After this, he styled himself in charters by titles such as "king of the English", or grandiosely, "king of the whole of Britain". In 934, he invaded Scotland and in 937, an alliance of armies of Scotland, Strathclyde, and the Vikings invaded England. Æthelstan secured a decisive victory at the Battle of Brunanburh, cementing his dominant position in Britain.[3] Æthelstan died in October 939 and he was succeeded by his half-brother and Eadred's full brother Edmund. He was the first king to succeed to the throne of all England, but he soon lost control of the north. By the end of the year Anlaf Guthfrithson, the Viking king of Dublin, had crossed the sea to become king of York. He also invaded Mercia and Edmund was forced to surrender the Five Boroughs of north-east Mercia to him. Guthfrithson died in 941 and in 942, Edmund was able to recover the Five Boroughs. In 944, he recovered full control of England by expelling the Viking kings of York. On 26 May 946 he was stabbed to death trying to protect his seneschal from attack by a convicted outlaw at Pucklechurch in Gloucestershire, and as his sons were young children Eadred became king.[4]

Family and early life

Eadred's father, Edward the Elder, had three wives, eight or nine daughters, several of whom married Continental royalty, and five sons. Æthelstan, the son of Edward's first wife, Ecgwynn, was born around 894, but she probably died around the time of Alfred's death, as by 901 Edward was married to Ælfflæd. In about 919 he married Eadgifu, who had two sons, Edmund and Eadred. According to the twelfth-century chronicler William of Malmesbury, Edmund was about eighteen years old when he succeeded to the throne in 939, which dates his birth to 920–921, and their father Edward died in 924, so Eadred was born around 923.[5] He had one or two full sisters. Eadburh was a nun at Winchester who was later venerated as a saint. William of Malmesbury gives Eadred a second full sister called Eadgifu like her mother, who married Louis, prince of Aquitaine. William's account is accepted by the historians Ann Williams and Sean Miller, but Æthelstan's biographer Sarah Foot argues that she did not exist, and that William confused her with Ælfgifu, a daughter of Ælfflæd.[6]

Eadred grew up with his brother at Æthelstan's court, and probably also with two important Continental exiles, his nephew Louis, future King of the West Franks, and Alain, future Duke of Brittany. According to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan showed great affection towards Edmund and Eadred: "mere infants at his father's death, he brought them up lovingly in childhood, and when they grew up gave them a share in his kingdom".[7] At a royal assembly shortly before Æthelstan's death in 939, Edmund and Eadred attested charter S 446,[lower-alpha 1] which granted land to their full sister, Eadburh. They both attested as regis frater (king's brother).[8] This is the only charter of Æthelstan attested by Eadred.[9]

Eadgifu and Eadred attested many of Edmund's charters, showing a high degree of family cooperation; initially Eadgifu attested first, but from sometime in late 943 or early 944 Eadred took precedence, perhaps reflecting his growing authority. Eadgifu attested around one-third of Edmund's charters, always as regis mater (king's mother), including all grants to religious institutions and individuals. Eadred attested over half,[lower-alpha 2] and Pauline Stafford comments: "No other adult male of the West Saxon house was ever given such prominence before his accession."[11]

Reign

Battle for control of Northumbria

Like Edmund, Eadred inherited the whole English kingdom, but soon lost Northumbria and had to fight to get it back. The situation was complicated due to the number of rival factions in Northumbria. The Viking Anlaf Sihtricson (also called Olaf Sihtricson and Amlaib Cuaran) ruled Dublin and the southern Northumbrian kingdom of York at different periods. When king of York in the early 940s he had accepted baptism with Edmund as his godfather, indicating submission to his rule, and his coins followed English designs, but Edmund had expelled him in 944. Both Anlaf and the Norse (Norwegian) prince Erik Bloodaxe[lower-alpha 3] ruled York for periods during Eadred's reign. Erik issued coins with a Viking sword design and represented a more serious threat to West Saxon power than Anlaf.[14] The York magnates were key players, led by the powerful Wulfstan, Archbishop of York, who periodically made bids for independence by accepting Viking kings, but submitted to southern rule at other times. In the view of the historian Marios Costambeys, Wulfstan's influence in Northumbria appears to have been greater than Erik's.[15] Osulf, the Anglo-Saxon ruler of the north Northumbrian territory of Bamburgh, supported Eadred when it was in his own interest. The sequence of events is very unclear because different manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle contradict each other, and they also conflict with the evidence of charters, which are the only contemporary sources.[16] Charters of 946, 949–50 and 955 call Eadred ruler of the Northumbrians, and these provide evidence of periods when York submitted to southern rule.[17]

Following Edmund's death, Charter S 521 states that "it happened that Eadred, his uterine brother, [was] chosen in his stead by the nobles".[18] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, he immediately "reduced all Northumbria under his rule" and obtained promises of obedience from the Scots. He may have invaded Northumbria in response to a rebellion supported by the Scots.[19] He was crowned by Archbishop Oda of Canterbury on 16 August 946 at Kingston upon Thames, attended by Hywel Dda, king of Deheubarth in south Wales, Wulfstan and Osulf. The following year at Tanshelf, near the border between Northumbria and Mercia, Wulfstan and the other York magnates pledged allegiance to him.[20]

The York magnates soon reneged on their promises and accepted Erik as king. Eadred responded by leading an army to Ripon, where he burnt down the Minster, no doubt to punish Wulfstan, as it was at the centre of his richest estate.[21] The Northumbrians sought revenge: according to version D of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, "when the king was on his way home, the army (which) was in York overtook the king's army at Castleford, and they made a great slaughter there. Then the king became so angry that he wished to march back into the land and destroy it utterly. When the councillors of the Northumbrians understood that, they deserted Erik and paid to King Eadred compensation for their act."[22] Within a year or two they again changed sides and installed Anlaf Sihtricson as king. In 952 Eadred arrested Wulfstan and in the same year Erik displaced Anlaf, but in 954 the York magnates again threw out Erik and returned to English rule, this time not due to an invasion but by the choice of the northerners, and the change proved to be permanent.[23] Erik was assassinated shortly afterwards, possibly at the instigation of Osulf, and the historian Frank Stenton comments that the time was past when an individual adventurer could establish a dynasty in England.[24][lower-alpha 4] Wulfstan was later released, probably in early 955, but he was apparently not allowed to resume his archbishopric and instead given the bishopric of Dorchester-on-Thames.[30] Eadred then appointed Osulf as the first ealdorman of the whole of Northumbria. Osulf's position was probably so strong that the king had no choice but to appoint him, and it was not until the next century that southern kings were able to make their own choice of ealdormen in Bamburgh itself.[31] In his will, Eadred left 1600 pounds[lower-alpha 5] to be used for protection of his people from famine or to buy peace from a heathen army, showing that he did not regard England as safe from attack.[33]

Administration

Charters issued in the 930s and the 940s suggest continuity of royal government and smooth transitions between the reigns of Æthelstan, Edmund and Eadred.[34] Eadred's principal councillors were mainly people he had inherited from his brother Edmund, and in a few cases went back to his half-brother Æthelstan. Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Ealdorman Æthelstan of East Anglia, had been advisers of King Æthelstan who had become dominant under Edmund. Ealdorman Æthelstan's power under Edmund and Eadred was so great that he became known as Æthelstan Half-King.[35] His prestige was further increased when his wife Ælfwynn became foster-mother to Edmund's younger son Edgar following his mother's early death. The Half-King's brother Eadric was ealdorman of central Wessex, and Eadred granted him land in Sussex which Eadric gave to Abingdon Abbey.[36] Dunstan, the Abbot of Glastonbury and a future Archbishop of Canterbury, was one of Eadred's most trusted friends and advisers, and he attested many of Eadred's charters.[37] Eadgifu had been sidelined under the rule of her stepson Æthelstan, but she became powerful under the rule of her own sons Edmund and Eadred.[38] Ælfgar, the father of Edmund's second wife Æthelflæd, was ealdorman of Essex from 946 to 951. Edmund presented Ælfgar with a sword decorated with gold on its hilt and silver on its sheath, which Ælfgar subsequently gave to Eadred. Ælfgar consistently attested last among the ealdormen, and he may have been subordinate to Æthelstan Half-King.[39] Two thegns, Wulfric Cufing and another Wulfric who was Dunstan's brother, received massive grants of land from Edmund and Eadred, showing that royal patronage could transform minor local figures into great nobles.[40]

Eadred is one of the few later Anglo-Saxon kings for whom no law code is known to survive, although he may have issued the Hundred Ordinance.[41] Ealdormen issued legal judgments on behalf of the king at a local level. One example during Eadred's reign concerned the theft of a woman, probably a slave. A man called Æthelstan of Sunbury was later found to have her in his possession and could not prove he had acquired her legally. He surrendered possession and paid compensation to the owner, but Ealdorman Byrhtferth ordered him to pay his wer (the value of his life) to the king, and when Æthelstan could not pay Byrhtferth required him to forfeit his Sunbury estate.[42] In 952 Eadred ordered "a great slaughter" of the people of Thetford in revenge for their murder of Abbot Eadhelm, perhaps of St Augustine's, Canterbury. This was the usual punishment for crimes committed by communities.[43] The historian Cyril Hart suggests that Eadhelm may have been trying to establish a new monastery there, against the opposition of the local inhabitants.[44] Force was fundamental to West Saxon kings' domination of England, and the historian George Molyneaux sees the Thetford slaughter as an example of their "intermittently unleashed crude but terrifying displays of coercive power".[45]

The Anglo-Saxon court was peripatetic, travelling around the country, and there was no fixed capital.[46] Like other later Anglo-Saxon kings, Eadred's royal estates were mainly in Wessex and he and his court travelled between them. All known locations in Eadred's itinerary were in Wessex, apart from Tanshelf.[47] There was also no central treasury, but Eadred did travel with his sacred relics, which were in the custody of his mass priests.[48] According to Dunstan's first biographer, Eadred "handed over to Dunstan his most valuable possessions: many land charters, the old treasure of earlier kings, and various riches of his own acquiring, all to be guarded faithfully behind the walls of his monastery".[49] However, Dunstan was only one of the people entrusted with Eadred's treasures; there were others such as Wulfhelm, Bishop of Wells. When Eadred was dying, he sent for the property so that he could distribute it, but he died before Dunstan arrived with his share.[50] Ceremonial was important. A charter issued at Easter 949 describes Eadred as "exalted with royal crowns",[51] displaying the king as an exceptional and charismatic character set apart from other men.[52]

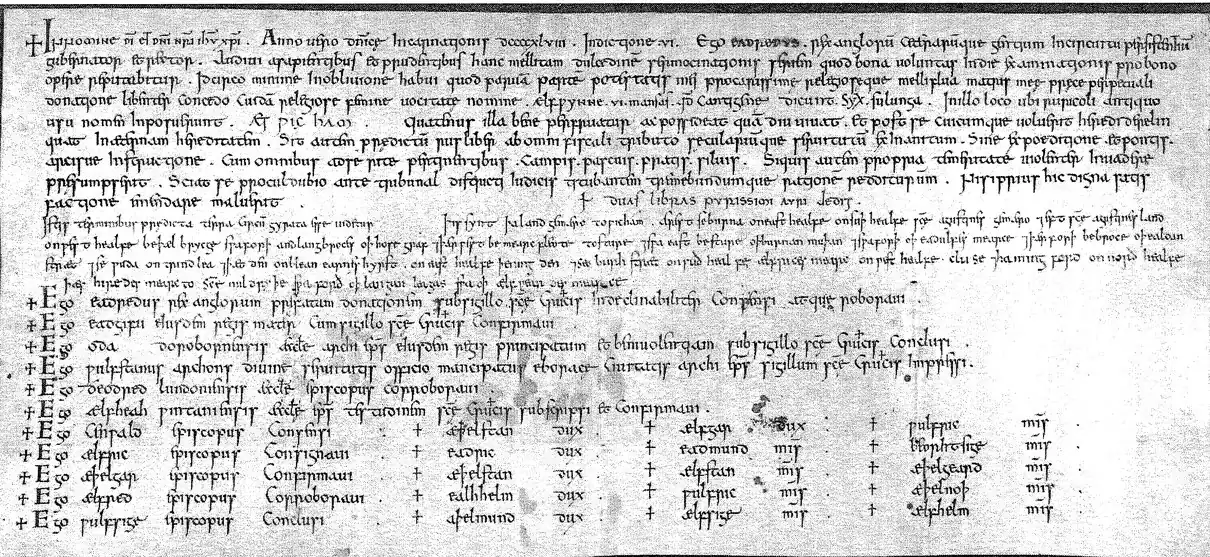

Charters

The period between 925 and 975 was the golden age of Anglo-Saxon royal diplomas,[lower-alpha 6] when they were at their peak as instruments of royal government, and kings used them to project images of royal power and as the most reliable means of communication between the court and the country.[54] Most charters between late in Æthelstan's reign and midway through Eadred's were written in the king's writing office in a style called the "diplomatic mainstream", for example, the charter which is displayed below, written by the scribe called "Edmund C". He wrote two charters dating to Edmund's reign and three in Eadred's. The style almost disappears between around 950 and the end of Eadred's reign. The number of surviving charters declines, with none dating to the years 952 and 954.[55] Charters from this period belong to two other traditions. The reason for the dramatic change in around 950 is not known, but may be due to Eadred transferring responsibility for charter production from the royal writing office to other centres when his health declined in his last years.[56]

One alternative tradition is found in the "alliterative charters", produced between 940 and 956, which display frequent use of alliteration and unusual vocabulary, in a style influenced by Aldhelm, the seventh-century bishop of Sherborne. They are the work of a scribe who was very learned, almost certainly someone in the circle of Cenwald, bishop of Worcester or perhaps the bishop himself. They have Mercian antecedents and most relate to estates north of the Thames. Seven charters of this type survive from 949 to 951, half the total for those years, and another two are dated 955.[58] The historian Simon Keynes comments:

- The "alliterative" charters represent an extraordinary body of material, intimately related to each other, and deeply interesting in their own right as works of learning and literature. Judged as diplomas, they are inventive, spirited, and delightfully chaotic. They stand apart from the diplomatic mainstream, yet they seem nonetheless to emerge from the very heart of the ceremonies of conveyance conducted at royal assemblies.[59]

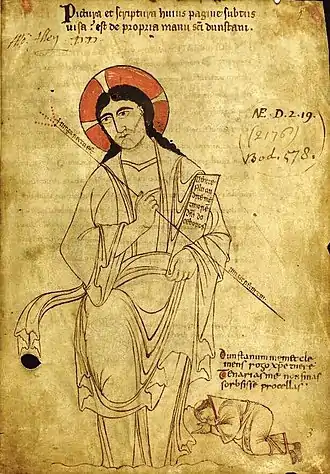

The other alternative tradition is found in the "Dunstan B" charters, which are very different from the "alliterative" charters, with a style which is plain and unpretentious, and which dispenses with the usual initial invocation and proem. They are associated with Dunstan and Glastonbury Abbey, and all the ones issued in Eadred's reign are for estates in the south and west.[60] They were produced between 951 and 986,[61] but they appear to be foreshadowed by a charter of 949 granting Reculver minster and its lands to Christ Church, Canterbury, which claims to be written by Dunstan "with his own fingers". The document is not original and is thought to be a production of the later tenth century, but there are no anachronisms and it has many stylistic features of the "Dunstan B" charters, so it is probably an "improved" version of an original charter.[62] Further evidence associating Dunstan with the charters is provided by commentaries on a manuscript of Caesarius of Arles's Expositio in Apocalypsin, written on Dunstan's order, which has a script so similar to that of the only "Dunstan B" charter to survive as an original manuscript that it is likely that both documents were written by Glastonbury scribes. The charter is described by Keynes as "well disciplined and thoroughly professional".[63] Eight charters of all types survive dating to 953 and 955, out of which six belong to this tradition and two are "alliterative". The six "Dunstan B" charters are not witnessed by the king, and Dunstan was probably authorised to produce charters in the king's name when he was too ill to carry out his duties.[64]

In the 940s the draftsmen of "mainstream" charters used the title "king of the English" and in the early 950s "Dunstan B" charters described Eadred as "king of Albion", whereas "alliterative" charters adopted complex political analysis in the wording of Eadred's title, and only after the final conquest of York described him as "king of the whole of Britain".[65] Several "alliterative" charters, including one issued on the occasion of Eadred's coronation, use expressions such as "the government of kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons and Northumbrians, of the pagans and the Britons".[66] Keynes observes: "It would be dangerous, of course, to press such evidence too far; but it is interesting nonetheless to be reminded that in the eyes of at least one observer, the whole was no greater than the sum of its component parts.[34]

Coinage

_obverse.jpg.webp)

_reverse.jpg.webp)

The only coin in common use in late Anglo-Saxon England was the silver penny.[68] Halfpennies were very rare but a few have been found dating to Eadred's reign, one of which has been cut in half to make a farthing. The average weight of a penny of around 24 grains in Edward the Elder's reign gradually declined until Edgar's pre-reform coinage, and by Eadred's time the reduction was about 3 grains.[69] With a few exceptions, the high silver content of 85 to 90% in previous reigns was maintained under Eadred.[70]

One common coin type in Eadred's reign is designated BC (bust crowned), with the king's head on the obverse. Many BC coins are based on an original style of Æthelstan's reign but are of crude workmanship. Some were produced by moneyers who had worked in the previous reign, but there were over thirty new moneyers producing BC coins, out of which nearly twenty are represented by a single coin, so it is likely that there were other moneyers producing BC coins whose coins have not yet been found.[71]

The H (Horizontal) type, with no king's bust on the obverse and the moneyer's name horizontally on the reverse, was even more common, with more than eighty moneyers known for Eadred's reign, many only from single specimens.[72] The dominant styles in Eadred's reign were HT1 in the south and east, with trefoils top and bottom on the reverse (see right), and HR1 in the north midlands, with rosettes instead of trefoils, produced by around sixty moneyers and the most plentiful style in Eadred's reign.[73]

In Northumbria and the north-east in Eadred's reign there were a few moneyers with a large output, whereas coins in the rest of the country were produced by many different moneyers.[74] The mint town is shown on some BC coins, but rarely on H types. A few HRs show Derby and Chester, and one HT1 coin survives with an Oxford inscription and one with Canterbury.[75] The leading York moneyer for almost the whole of Eadred's reign was Ingelgar (see right). He produced high-standard coins for Eadred, Anlaf and Erik and worked until the last months of Eadred's reign, when he was replaced by Heriger. Another large-scale moneyer was Hunred, who may have operated at Derby when York was in Viking hands.[76]

Religion

The major religious movement of the tenth century, the English Benedictine Reform, reached its peak under Edgar, but Eadred was a strong supporter in its early stages.[78] Another proponent was Archbishop Oda, who was a monk with a strong connection with the leading Continental centre, Fleury Abbey. When Eadred came to the throne, two of the future leaders of the movement were at Glastonbury Abbey: Dunstan had been appointed abbot by Edmund, and he had been joined by Æthelwold, the future Bishop of Winchester. The reformers also had lay supporters such as Æthelstan Half-King and Eadgifu, who were especially close to Dunstan.[79] The historian Nicholas Brooks comments: "The evidence is indirect and inadequate but may suggest that Dunstan drew much of his support from the regiment of powerful women in early tenth-century Wessex and from Eadgifu in particular." According to Dunstan's first biographer, Eadred urged Dunstan to accept the vacant see of Crediton, and when he refused Eadred got Eadgifu to invite Dunstan to a meal where she could use her "woman's gift of words" to persuade him, but her attempt was unsuccessful.[80]

During Eadred's reign, Æthelwold asked for permission to go abroad to gain a deeper understanding of the scriptures and a monk's religious life, no doubt at a reformed monastery such as Fleury.[81] He may have thought that the discipline at Glastonbury was too lax.[4] Eadred refused his mother's advice that he should not allow such a wise man to leave his kingdom, instead appointing him as abbot of Abingdon, which was then served by secular priests and which Æthelwold transformed into a leading Benedictine abbey. Eadred supported the community, including granting it a 100 hide royal estate at Abingdon, and Eadgifu was an even more generous donor.[82] Eadred travelled to Abingdon to plan the monastery there and personally measured the foundations where he proposed to raise the walls. Æthelwold then invited him to dine and he accepted. The king ordered that the mead should flow plentifully and the doors were locked so that none would be seen leaving the royal dinner. Some Northumbrian thegns accompanying the king got drunk, as was their custom, and were very merry when they left. However, Eadred died before the work could be carried out, and the building was not constructed until Edgar came to the throne.[83]

Supporters of monastic reform were devoted to cults of saints and their relics. When Eadred burnt down Ripon Minster during his invasion of Northumbria, Oda had the relics of Saint Wilfrid, and Ripon's copy of the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi by Eddius (Stephen of Ripon), seized and brought to Canterbury. The Vita provided the basis for a new metrical life of Wilfrid (Breuiloquium Vitae Wilfridi) by Frithegod, a Frankish scholar in Oda's household, and a preface in Oda's name (although probably drafted by Frithegod) justified the theft by accusing Ripon of scandalous neglect of Wilfrid's relics.[84] Michael Lapidge sees the destruction of the minster as providing the pretext for "a notorious furtum sacrum" (sacred theft).[85] Wilfrid had been an assertively independent northern bishop and in the historian David Rollason's view the theft may have been intended to prevent the relics from becoming a focus for opposition to the West Saxon dynasty.[86] Kings were also avid collectors of relics, which demonstrated their piety and increased their prestige, and Eadred left bequests in his will to priests he had appointed to look after his own relics.[87]

Under Edgar, the view of Æthelwold and his circle that Benedictine monasticism was the only worthwhile form of religious life became dominant, but this was not the view of earlier kings such as Eadred.[88] In 951 he appointed Ælfsige, a married man with a son, as bishop of Winchester.[16] Ælfsige was not a reformer and was later remembered as hostile to the cause.[89] Eadred's reign saw a continuation of a trend away from ecclesiastical beneficiaries of charters. More than two-thirds of beneficiaries in Æthelstan's reign were ecclesiastics and two-thirds were laymen in Edmund's. Under Eadred and Eadwig, three-quarters were laymen.[90]

In the mid-tenth century, some religious noblewomen received grants of land without being members of communities of nuns.[91] Æthelstan granted two estates, Edmund seven and Eadred four. After this the practice ceased abruptly, apart from one further donation. The significance of the donations is uncertain, but the most likely explanation is that some aristocratic women were granted the estates so that they could pursue a religious vocation in their own way, whether by establishing a nunnery or living a religious life in their own homes.[92] In 953 Eadred granted land in Sussex to his mother, and she is described in the charter as famula Dei, which probably means that she adopted a religious life while retaining her own estates, and did not enter a monastery.[93]

Learning

Glastonbury and Abingdon were leading centres of learning, and Dunstan and Æthelwold were both excellent Latinists, but little is known of the studies at their monasteries. Oda was also a competent Latin scholar and his household at Canterbury was the other main centre of learning in the mid-tenth century. The most brilliant scholar there was Frithegod. His poem Breuiloquium Vitae Wilfridi is described by Lapidge, an expert on medieval Latin literature, as "perhaps the most remarkable monument of tenth-century Anglo-Latin literature".[94] It is "one of the most brilliantly ingenious – but also damnably difficult – Latin products of Anglo-Saxon England",[95] which "may be dubiously described as the 'masterpiece' of Anglo-Latin hermeneutic style".[96] Frithegod was a tutor to Oda's nephew Oswald, a future Archbishop of York and the third leader of the monastic reform movement. Frithegod returned to Francia when his patron Oda died in 958.[97]

Eadred's will

Eadred's will is one of only two wills of Anglo-Saxon kings to survive.[99][lower-alpha 9] It reads:

- In nomine Domini. This is King Eadred's will. In the first place, he presents to the foundation wherein he desires that his body shall rest, two gold crosses and two swords with hilts of gold, and four hundred pounds. Item, he gives to the Old Minster at Winchester three estates, namely Downton, Damerham and Calne. Item, he gives to the New Minster three estates, namely Wherwell, Andover and Clere; and to the Nunnaminster, Shalbourne, Thatcham and Bradford. Item, he gives to the Nunnaminster at Winchester thirty pounds. and thirty to Wilton, and thirty to Shaftesbury.

- Item, he gives sixteen hundred pounds for the redemption of his soul, and the good of his people, that they may be able to purchase for themselves relief from want and from the heathen army, if they need [to do so]. Of this the Archbishop at Christchurch is to receive four hundred pounds, for the relief of the people of Kent and Surrey and Sussex and Berkshire; and if anything happen to the bishop, the money shall remain in the monastery, in the charge of the members of the council who are in that county. And Ælfsige, bishop of the see of Winchester, is to receive four hundred pounds, two hundred for Hampshire and one hundred each for Wiltshire and Dorsetshire; and if anything happen to him, it shall remain-as in a similar case mentioned above-in the charge of the members of the council who are in that county. Item, Abbot Dunstan is to receive two hundred pounds and to keep it at Glastonbury for the people of Somerset and Devon; and if anything happen to him, arrangements similar to those above shall be made. Item, Bishop Ælfsige is to receive the two hundred pounds left over, and keep [the money] at the episcopal see at Winchester, for whichever shire may need it. And Bishop Oscetel is to receive four hundred pounds, and keep it at the episcopal see at Dorchester for the Mercians, in accordance with the arrangement described above. Now Bishop Wulfhelm has that sum of four hundred pounds (?). Item, gold to the amount of two thousand mancuses is to be taken and minted into mancuses;[lower-alpha 10] and the archbishop is to receive one portion, and Bishop Ælfsige a second, and Bishop Oscetel a third, and they are to distribute them throughout the bishoprics for the sake of God and for the redemption of my soul.

- Item, I give to my mother the estates at Amesbury and Wantage and Basing, and all the booklands which I have in Sussex, Surrey and Kent, and all those which she has previously had. Item I give to the archbishop two hundred mancuses of gold, reckoning the hundred at a hundred and twenty. And to each of my bishops one hundred and twenty mancuses of gold. And to each of my earls one hundred and twenty mancuses of gold. And to each [duly] appointed seneschal, and each appointed chamberlain and butler, eighty mancuses of gold. And to each of my chaplains whom I have put in charge of my relics, fifty mancuses of gold and five pounds in silver. And five pounds to each of the other priests. And thirty muncuses of gold to each [duly] appointed steward, and to every ecclesiastic who has been appointed (?) since I succeeded to the throne, and to every member of my household, in whatever capacity he be employed, unless he be.......to the royal palaces.

- Item, I desire that twelve almsmen be chosen on each of the estates mentioned above, and if anything happen to any of them, another is to be put appointed his place; and this is to hold good so long as Christianity endures, to the glory of God and the redemption of my soul; and if anyone refuses to carry it out, his estate is to revert to the place where my body shall rest.[102]

The will is described by Stenton as "the chief authority for the pre-Conquest royal household". It shows that discthegns (seneschals) served at his table and that the other principal officers were butlers and hræglthegns (keepers of the wardrobe).[103] All the estates named in the will are in Wessex, reflecting the concentration of royal property there, although he also mentions booklands in the south-east without specifying the locations.[104] Eadwig cannot have been happy at his exclusion from the will, and it appears to have been set aside following his accession.[105]

Illness and death

Eadred suffered from ill health at the end of his life which gradually got worse and led to his early death.[16] Dunstan's first biographer, who probably attended court as a member of his household, wrote:

- Unfortunately Dunstan's beloved King Eadred was very sickly all through his reign. At mealtimes he would suck the juice out of his food, chew what was left of it for a little and then spit it out: a practice that often turned the stomachs of the thegns dining with him. He dragged on an invalid existence as best he could, despite the protests of his body (?), for quite a long time. Finally his worsening illness came over him more and more often with a thousandfold weight, and brought him unhappily to his deathbed.[107]

The eleventh-century hagiographer Herman the Archdeacon described Eadred as "debilis pedibus" (crippled in both feet),[108] and in his later years he probably delegated authority to leading magnates such as Dunstan.[109] Meetings of the witan were rarer when he was ill and business was limited, with no appointments of ealdormen.[110] He did not marry, perhaps due to his poor health, and he died in his early thirties on 23 November 955, at Frome in Somerset.[16]

He was buried in the Old Minster, Winchester,[lower-alpha 11] although that was probably not his choice as in his will he made bequests to an unspecified location where "he wishes his body to rest", and then property to the Old Minster, implying that they were different places. Eadwig and Ælfsige, bishop of Winchester, may have decided on the burial place.[112] The historian Nicole Marafioti suggests that Eadred may have wished to be buried at Glastonbury and Eadwig insisted on Winchester in order to prevent Eadred's supporters from using the grave as "ideological leverage" against the new regime.[113]

Assessment

Domestic politics and recovering control over the whole of England were central to Eadred's rule and, unlike Æthelstan and Edmund, he is not known to have played any part in West Frankish politics, although in 949 ambassadors from Eadred attended the court of Otto I, King of East Francia at Aachen. Securing a general recognition of his authority was Eadred's primary duty, and his main preoccupation was dealing with northern rebellions.[114] Northumbria fought for its independence against successive West Saxon kings, but the acceptance of Erik proved to be its last throw and it was finally conquered during Eadred's reign.[115] Historians disagree on how great his role was. In the view of the historian Ben Snook, Eadred "relied on a kitchen cabinet to run the country on his behalf and seems never to have exercised much direct authority."[116]

Hart suggests that in Edmund's reign, Eadgifu and Æthelstan Half-King decided much of national policy, and the position did not change much under Eadred.[117] By contrast, in Williams's view, Eadred was "clearly an able and even energetic king, hampered by debility and (at the last) by a serious illness which brought about his early death".[16]

Eadred's attitude towards his nephews is uncertain. Some charters are attested by both Eadwig and Edgar as cliton (medieval Latin for prince), but others by Eadwig as cliton or ætheling (Old English for prince) and Edgar as his brother.[118] When he acceded, Eadwig dispossessed Eadgifu and exiled Dunstan, apparently as part of an attempt to free himself from the powerful advisers of his father and uncle. The attempt failed, as within two years he was forced to share the kingdom with Edgar, who became King of the Mercians, while Eadwig retained Wessex. Eadwig died in 959 after a rule of only four years.[119]

Notes

- A charter's S number is its number in Peter Sawyer's list of Anglo-Saxon charters, available online at the Electronic Sawyer.

- Eadred almost always attested Edmund's charters as frater regis (king's brother). Two exceptions are "S 505". with cliton (medieval Latin for prince) and "S 511". with cliton et frater regis.[10]

- Most historians identify the Erik who ruled York with Erik Bloodaxe, the son of King Harald Fairhair of Norway, but Clare Downham argues that the two Eriks were different people.[12] See also the discussion by Alex Woolf.[13]

- The chronology is very confused,[25] but most historians accept the sequence of events given here,[26] although they give varying dates. For example, Alex Woolf dates the start of Anlaf's kingship to late 949, whereas Sean Miller thinks that it started in late 950 or 951.[27] Peter Sawyer and Ann Williams argue that Erik only had one period of rule.[28] See also the discussion by Downham.[29]

- In this period a pound was not a coin but a unit of account equivalent to 240 pence.[32]

- Charters or diplomas were legal instruments granting land or privileges by the king to an individual or religious house. They were usually written in Latin on a single sheet of parchment.[53]

- M stands for Moneta (Moneyer). This coin is classified as HT1, with a reverse which has the moneyer's name shown horizontally, three crosses in the middle and trefoils top and bottom.[67]

- The mid-fifteenth century Liber Abbatiæ has the only surviving copy of King Eadred's will. The will in Old English is on f. 23r, translation into Middle English ff. 23r to 23v, and translation into Latin 23v to 24r. The Old English version was printed and translated by Florence Harmer in 1914, and translated by Dorothy Whitelock in 1955 (2nd edition 1979). All three versions were printed by Sean Miller in 2001.[98] Harmer's translation is given here for copyright reasons.

- The other king's will to survive is that of Alfred the Great.[100]

- A mancus could be a weight of gold or a coin worth 30 pence. Very few mancuses survive and they may have only been produced in quantity for ceremonial purposes.[101]

- The Old Minster was demolished in the late eleventh century and replaced with Winchester Cathedral.[111] There are six mortuary chests in the cathedral labelled with the names of Anglo-Saxon monarchs, one of them Eadred. In 1642 Parliamentary Civil War troops emptied the chests and the bones were mixed up, so each chest contains the bones of a variety of people.[106]

References

- Keynes & Lapidge 1983, pp. 9, 12–13, 24–25, 37–38, 41–44; Costambeys 2004a.

- Miller 2004.

- Foot 2011a.

- Williams 2004a.

- Miller 2004; Foot 2011b, pp. 31, 50–51; Mynors, Thomson & Winterbottom 1998, p. 229.

- Foot 2011b, p. 45, 50–51; Williams 2004a; Miller 2004; Mynors, Thomson & Winterbottom 1998, p. 201.

- Foot 2011b, pp. 43, 52–53; Mynors, Thomson & Winterbottom 1998, p. 229.

- Roach 2013, p. 40; "S 446".

- Keynes 2002, Table XXXIa (2 and 3 of 6).

- Keynes 2002, Table XXXIa (3–5 of 6); Dumville 1979, pp. 6–8.

- Stafford 1981, p. 25; Trousdale 2007, pp. 143–145, 213, 215; Keynes 2002, Table XXXIa (3–5 of 6).

- Stenton 1971, p. 360; Costambeys 2004b; Downham 2007, pp. 115–120.

- Woolf 2007, pp. 187–188.

- Williams 2004a; Williams 2004b.

- Hart 2004; Costambeys 2004b.

- Williams 2004b.

- Miller 2014, p. 154.

- Whitelock 1979, p. 551; "S 521".

- Downham 2007, p. 112; Whitelock 1979, p. 222.

- Williams 2004b; Whitelock 1979, pp. 222, 551–552; Downham 2007, p. 113.

- Woolf 2007, p. 186.

- Whitelock 1979, p. 223; Williams 2004b.

- Stenton 1971, p. 361 and n. 1; Woolf 2007, pp. 189–190.

- Stenton 1971, pp. 362–363.

- Williams 1999, p. 87.

- Sawyer 1995, p. 39.

- Woolf 2007, p. 186; Miller 2014, p. 155.

- Sawyer 1995, pp. 39–44; Williams 2004b.

- Downham 2003, pp. 25–51.

- Hart 2004.

- Huscroft 2019, p. 149; Molyneaux 2015, pp. 67 n. 91, 178–179.

- Naismith 2014a, p. 330.

- Yorke 1995, p. 132; Whitelock 1979, p. 555.

- Keynes 1999, p. 473.

- Williams 2004a; Williams 2004b; Lapidge 2009, p. 85.

- Hart 1992, pp. 574, 579.

- Brooks 1984, p. 234; Huscroft 2019, p. 181.

- Stafford 2004.

- Hart 1992, pp. 127–129.

- Brooks 1992, pp. 8–10.

- Williams 2013, p. 8 n. 40; Williams 1999, p. 93.

- Molyneaux 2015, pp. 72, 111.

- Stenton 1971, pp. 562–563; Whitelock 1979, p. 223.

- Hart 1992, p. 600.

- Molyneaux 2015, p. 78.

- Stenton 1971, p. 539.

- Yorke 1995, pp. 101–102; Hill 1981, Map 158.

- Chaplais 1973, p. 48; Whitelock 1979, pp. 555–556.

- Winterbottom & Lapidge 2011, p. 61.

- Winterbottom & Lapidge 2011, p. 65; Whitelock 1979, p. 555 and n. 6; Brooks 1992, pp. 13–14.

- Huscroft 2019, p. 140; Molyneaux 2015, p. 55 n. 34; "S 549".

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 18–19.

- Keynes 2014a, p. 102.

- Keynes 2013, pp. 52–53; Snook 2015, p. 154.

- Keynes 2013, pp. 56–57, 78; Snook 2015, pp. 132–133.

- Keynes 1999, pp. 474–475.

- Brooks & Kelly 2013, pp. 923–929; "S 535".

- Snook 2015, pp. 132–133, 136–143; Keynes 2014b, p. 279.

- Keynes 2013, p. 95.

- Snook 2015, pp. 137–138, 143; Keynes 1994, pp. 180–181.

- Keynes 1994, pp. 173–179.

- Brooks & Kelly 2013, pp. 940–942; "S 546".

- Chaplais 1973, p. 47; Keynes 1994, pp. 186–187; Keynes 2013, p. 96; "S 563".

- Snook 2015, p. 133; Keynes 1994, pp. 185–186; Keynes 2002, Table XXIX.

- Keynes 2008, pp. 6–7.

- Keynes 1997, pp. 70–71; Whitelock 1979, p. 551; ("S 520". ))

- Blunt, Stewart & Lyon 1989, pp. 13–15.

- Grierson & Blackburn 1986, p. 270; Naismith 2014a, p. 330.

- Blunt, Stewart & Lyon 1989, pp. 137–138, 237.

- Naismith 2014b, p. 69.

- Blunt, Stewart & Lyon 1989, pp. 11–12, 191–192.

- Blunt, Stewart & Lyon 1989, pp. 13–15, 130.

- Blunt, Stewart & Lyon 1989, pp. 16, 134–135.

- Blunt, Stewart & Lyon 1989, p. 130.

- Blunt, Stewart & Lyon 1989, pp. 134–135.

- Blunt, Stewart & Lyon 1989, pp. 130–132, 193.

- Dodwell 1982, pp. 53–54.

- Blair 2005, p. 347; Williams 1991, p. 113.

- Williams 2004a; Williams 2004b; Brooks 1992, p. 12.

- Brooks 1992, p. 12; Winterbottom & Lapidge 2011, p. 63.

- Lapidge & Winterbottom 1991, pp. xliii, 19; Yorke 2004.

- Yorke 2004; Lapidge & Winterbottom 1991, pp. 19–21; Thacker 1988, p. 43.

- Thacker 1988, pp. 56–57; Whitelock 1979, p. 906; Lapidge & Winterbottom 1991, pp. 23–25.

- Cubitt & Costambeys 2004; Thacker 1992, p. 235.

- Lapidge 1993, p. 157.

- Rollason 1989, pp. 152–153.

- Rollason 1986, pp. 91–92.

- Blair 2005, pp. 348–349.

- Marafioti 2014, p. 69.

- Stafford 1989, p. 37.

- Brooks1992, p. 7 and n. 24.

- Dumville 1992, pp. 177–178.

- Foot 2000, pp. 141, 181–182; "S 562".

- Lapidge 1993, pp. 25–30.

- Lapidge 1988, p. 46.

- Lapidge 1975, p. 78.

- Lapidge 1988, pp. 47, 65.

- British Library, Add MS 82931, ff, 23r-24r; Harmer 1914, pp. 34–35, 64–65, 119–123; Whitelock 1979, pp. 554–556; Miller 2001, pp. 76–81, 191–194; "S 1515".

- Keynes & Lapidge 1983, p. 173.

- Keynes & Lapidge 1983, pp. 174–178.

- Naismith 2014a, p. 330; Whitelock 1979, p. 555 n. 7.

- Harmer 1914, pp. 64–65.

- Stenton 1971, p. 639; Williams 1991, p. 113.

- Yorke 1995, p. 101; Hill 1981, Map 159.

- Keynes 1994, pp. 188–189; Brooks 1992, p. 14.

- Yorke 2021, pp. 61–63.

- Williams 2004b; Winterbottom & Lapidge 2011, p. 65.

- Williams 2004b; Licence 2014, pp. 8–9.

- Miller 2014, p. 155.

- Roach 2013, p. 212.

- Franklin 2004.

- Keynes 1994, p. 188 and n. 99; Whitelock 1979, p. 555; Yorke 2021, p. 71.

- Marafioti 2014, p. 79.

- Stenton 1971, p. 360; Wood 2010, p. 160.

- Higham 1993, p. 193.

- Snook 2015, p. 125.

- Hart 1992, p. 580.

- Biggs 2008, p. 137.

- Miller 2001, pp. 79–80.

Bibliography

- Biggs, Frederick (2008). "Edgar's Path to the Throne". In Scragg, Donald (ed.). Edgar King of the English: New Interpretations. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. pp. 124–139. ISBN 978-1-84383-399-4.

- Blair, John (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.}

- Blunt, Christopher; Stewart, Ian; Lyon, Stewart (1989). Coinage in Tenth-Century England: From Edward the Elder to Edgar's Reform. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-726060-9.

- "Liber de Hyda or Liber Abbatiae: a chronicle-cartulary of Hyde Abbey, AD 455-1023, compiled from earlier sources, Add MS 82931". British Library. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury. Leicester, UK: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-1182-1.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1992). "The Career of St Dunstan". In Ramsay, Nigel; Sparks, Margaret; Tatton-Brown, Tim (eds.). St Dunstan: His Life, Times and Cult. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-0-85115-301-8.

- Brooks, Nicholas; Kelly, Susan, eds. (2013). Charters of Christ Church Canterbury Part 2. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press for the British Academy. ISBN 978-0-19-726536-9.

- Chaplais, Pierre (1973). "The Anglo-Saxon Chancery: From the Diploma to the Writ". In Ranger, Felicity (ed.). Prisca Munimenta: Studies in Archival & Administrative History Presented to Dr A. E. J. Hollaender. London, UK: University of London Press Ltd. pp. 43–62. ISBN 978-0-340-17398-5.

- Costambeys, Marios (2004a). "Æthelred (d. 911)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52311. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Costambeys, Marios (2004b). "Erik Bloodaxe [Eiríkr Blóðöx, Eiríkr Haraldsson] (d. 954)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8907. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Cubitt, Catherine; Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Oda [St Oda, Odo] (d. 958), archbishop of Canterbury". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49265. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Dodwell, Charles (1982). Anglo-Saxon Art: A New Perspective. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-0861-0.

- Downham, Clare (2003). "The Chronology of the Last Scandinavian Kings of York, AD 937-954". Northern History. 40 (1): 25–51. doi:10.1179/007817203792207979. ISSN 1745-8706. S2CID 161092701.

- Downham, Clare (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Edinburgh: Dunedin. ISBN 978-1-906716-06-6.

- Dumville, David (1979). "The Ætheling: a Study in Anglo-Saxon Constitutional History". Anglo-Saxon England. 8: 1–33. doi:10.1017/s026367510000301x. ISSN 0263-6751. S2CID 159954001.

- Dumville, David (1992). Wessex and England from Alfred to Edgar. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-308-7.

- Foot, Sarah (2000). Veiled Women I: The Disappearance of Nuns from Anglo-Saxon England. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-0043-5.

- Foot, Sarah (2011a). "Æthelstan (Athelstan) (893/4–939), king of England". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/833.(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Foot, Sarah (2011b). Æthelstan: The First King of England. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12535-1.

- Franklin, M. J. (2004). "Walkelin (d. 1098)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28465. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Grierson, Philip; Blackburn, Mark (1986). Medieval European Coinage. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03177-6.

- Harmer, Florence, ed. (1914). Select English Historical Documents of the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 875733891.

- Hart, Cyril (1992). The Danelaw. London, UK: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-044-9.

- Hart, Cyril (2004). "Wulfstan (d. 955/6)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50493. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Higham, Nicholas (1993). The Kingdom of Northumbria: AD 350–1100. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton. ISBN 978-0-86299-730-4.

- Hill, David (1981). An Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-13684-2.

- Huscroft, Richard (2019). Making England 796-1042. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-18246-2.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (1983). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources. London, UK: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Keynes, Simon (1994). "The 'Dunstan B' Charters". Anglo-Saxon England. 23: 165–193. doi:10.1017/S026367510000452X. ISSN 0263-6751. S2CID 161883384.

- Keynes, Simon (1997). "The Vikings in England, c. 790-1016". In Sawyer, Peter (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 48–82. ISBN 978-0-19-820526-5.

- Keynes, Simon (1999). "England, c. 900–1016". In Reuter, Timothy (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. III. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 456–484. ISBN 978-0-521-36447-8.

- Keynes, Simon (2002). An Atlas of Attestations in Anglo-Saxon Charters, c. 670–1066. 1, Tables. Cambridge, UK: Dept. of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic, University of Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-9532697-6-1.

- Keynes, Simon (2008). "Edgar rex admirabilis". In Scragg, Donald (ed.). Edgar King of the English: New Interpretations. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. pp. 3–58. ISBN 978-1-84383-399-4.

- Keynes, Simon (2013). "Church Councils, Royal Assemblies and Anglo-Saxon Royal Diplomas". In Owen-Crocker, Gale; Schneider, Brian (eds.). Kingship, Legislation and Power in Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. pp. 17–182. ISBN 978-1-84383-877-7.

- Keynes, Simon (2014a). "Charters and Writs". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Second ed.). Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Keynes, Simon (2014b). "Koenwald". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Second ed.). Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 279–280. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Lapidge, Michael (1975). "The Hermeneutic Style in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Literature". Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 4: 67–111. doi:10.1017/S0263675100002726. S2CID 161444797.

- Lapidge, Michael (1988). "A Frankish scholar in tenth-century England: Frithegod of Canterbury/Fredegaud of Brioude". Anglo-Saxon England. 17: 43–65. doi:10.1017/S0263675100004014. S2CID 162109808.

- Lapidge, Michael; Winterbottom, Michael, eds. (1991). Wulfstan of Winchester: The Life of St Æthelwold. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822266-8.

- Lapidge, Michael (1993). Anglo-Latin Literature 900–1066. London, UK: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-012-8.

- Lapidge, Michael, ed. (2009). Byrhtferth of Ramsey: The Lives of St Oswald and St Ecgwine. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955078-4.

- Licence, Tom, ed. (2014). Herman the Archdeacon and Goscelin of Saint-Bertin: Miracles of St Edmund. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968919-4.

- Maddicott, John (2010). The Origins of the English Parliament, 924–1327. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958550-2.

- Marafioti, Nicole (2014). The King's Body: Burial and Succession in Late Anglo-Saxon England. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-4758-9.

- Miller, Sean, ed. (2001). Charters of the New Minster, Winchester. Anglo-Saxon Charters. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press for the British Academy. ISBN 978-0-19-726223-8.

- Miller, Sean (2004). "Edward [called Edward the Elder] (870s?–924), king of the Anglo-Saxons". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8514. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Miller, Sean (2014) [1st edition 1999]. "Eadred". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Molyneaux, George (2015). The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871791-1.

- Mynors, R. A. B.; Thomson, R. M.; Winterbottom, M., eds. (1998). William of Malmesbury: Gesta Regum Anglorum, The History of the English Kings. Vol. I. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820678-1.

- Naismith, Rory (2014a) [1st edition 1999]. "Money". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Second ed.). Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 329–330. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Naismith, Rory (2014b). "Prelude to Reform: Tenth-Century English Coinage in Perspective". In Naismith, Rory; Allen, Martin; Screen, Elina (eds.). Early Medieval Monetary History: Studies in Memory of Mark Blackburn. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 39–83. ISBN 978-0-367-59999-7.

- Roach, Levi (2013). Kingship and Consent in Anglo-Saxon England, 871–978. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03653-6.

- Rollason, David (1986). "Relic-cults as an instrument of royal policy c. 900—c. 1050". Anglo-Saxon England. 15: 91–103. doi:10.1017/S0263675100003707. ISSN 0263-6751. S2CID 153445838.

- Rollason, David (1989). Saints and Relics in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell Ltd. ISBN 978-0-631-16506-4.

- Sawyer, Peter (1995). "The Last Scandinavian Kings of York". Northern History. 31: 39–44. doi:10.1179/007817295790175462. ISSN 1745-8706.

- Snook, Ben (2015). The Anglo-Saxon Chancery: The History, Language and Production of Anglo-Saxon Charters from Alfred to Edgar. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-006-4.

- Stafford, Pauline (1981). "The King's Wife in Wessex 800-1066". Past and Present. 91: 3–27. doi:10.1093/past/91.1.3. ISSN 0031-2746.

- Stafford, Pauline (1989). Unification and Conquest. A Political and Social History of England in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-6532-6.

- Stafford, Pauline (2004). "Eadgifu (b. in or before 904, d. in or after 966), queen of the Anglo-Saxons, consort of Edward the Elder". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52307. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Stenton, Frank (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thacker, Alan (1988). "Æthelwold and Abingdon". In Yorke, Barbara (ed.). Bishop Æthelwold: His Career and Influence. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. pp. 43–64. ISBN 978-0-85115-705-4.

- Thacker, Alan (1992). "Cults at Canterbury: Relics and Reform under Dunstan and his Successors". In Ramsay, Nigel; Sparks, Margaret; Tatton-Brown, Tim (eds.). St Dunstan: His Life, Times and Cult. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-0-85115-301-8.

- Trousdale, Alaric (2007). Rex Augustissimus: Reassessing the Reign of King Edmund of England, 939-46 (PhD). University of Edinburgh. OCLC 646764020.

- Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. (1979) [1st edition 1955]. English Historical Documents, Volume 1, c. 500–1042 (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14366-0.

- Williams, Ann (1991). "Eadred, king of the English 946-55". In Williams, Ann; Smyth, Alfred P.; Kirby, D. P. (eds.). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. London, UK: Seaby. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-85264-047-7.

- Williams, Ann (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England, c. 500-1066. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-312-22090-7.

- Williams, Ann (2004a). "Edmund I (920/21–946)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8501. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Williams, Ann (2004b). "Eadred [Edred] (d. 955)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8510. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Williams, Ann (2013). "Introduction". In Owen-Crocker, Gale; Schneider, Brian (eds.). Kingship, Legislation and Power in Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-1-84383-877-7.

- Winterbottom, Michael; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (2011). The Early Lives of St Dunstan. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960504-0.

- Wood, Michael (2010). "A Carolingian Scholar in the Court of King Æthelstan". In Rollason, David; Leyser, Conrad; Williams, Hannah (eds.). England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876–1947). Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. pp. 135–162. ISBN 978-2-503-53208-0.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba: 789–1070. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

- Yorke, Barbara (1995). Wessex in the Early Middle Ages. London, UK: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-1856-1.

- Yorke, Barbara (2004). "Æthelwold [St Æthelwold, Ethelwold] (904x9–984)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8920. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Yorke, Barbara (2021). "Royal Burial in Winchester: Context and Significance". In Lavelle, Ryan; Roffey, Simon; Weikert, Katherine (eds.). Early Medieval Winchester: Communities, Authority and Power in an Urban Space, c.800-c.1200. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. pp. 59–80. ISBN 978-1-78925-623-9.

External links

- Edred at the official website of the British monarchy

- Eadred 16 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- Portraits of Edred, King of England at the National Portrait Gallery, London