Eduard Arnhold

Eduard Arnhold (10 June 1849 – 10 August 1925) was a German entrepreneur, coal magnate, patron of the arts and philanthropist from the famous Arnhold family.[1][2]

Life

Born in Dessau, Arnhold was the son of the Jewish doctor Adolph Arnhold (1808-1872) and his wife Mathilde Arnhold née Cohn (1826-1905). The bankers Georg and Max Arnhold were his brothers. Henry H. Arnhold was his great grand-nephew.

Coal magnate

Arnhold became one of the wealthiest entrepreneurs under the Kaiser and the Weimar republic in the Silesian bituminous coal industry[3] He was member of the supervisory board of the Dresdner Bank. In 1913, Wilhelm II, German Emperor appointed him as the first and only Jew to the Preußisches Herrenhaus. That he, as a non-converted Jew was "offered" a title of nobility, which he rejected, is a legend that originated in the 1920s, is not substantiated and is now regarded as improbable by researchers.[4]

Art Collector

Arnhold collected art and was friends with artists such as Max Liebermann, Arnold Böcklin, Adolph Menzel and Louis Tuaillon. In 1902, Arnhold acquired Max Liebermann's "Parrot Alley" .[5] He was a major patron of the arts in Berlin. In 1913 hedonated the Villa Massimo in Rome as a cultural institute to the Kingdom of Prussia. The Villa Massimo is now run by the Federal Republic of Germany, and selected artists still receive scholarships and accommodation there. The "Stiftung Eduard Arnhold Hilfsfonds" in the care of the Academy of Arts, Berlin also still grants scholarships for visual artists today.

In addition to his villa on Wannsee and a city flat, he acquired the Hirschfelde manor near Werneuchen at the turn of the century. He redesigned the park there into a sculpture park and brought together works of art by numerous contemporary artists, but also found objects from distant countries. In the park, for example, he had a marble fountain built that had been excavated in Herculaneum on Mount Vesuvius.

Social Philanthropist

In addition to art, Arnhold was also socially committed. In 1907, he donated the Youth Education Centre Kurt Löwenstein in Werftpfuhl, neighbouring Hirschfelde, named after his wife. In this orphanage for girls, the protégés received an education both in the arts and with a perspective for the labour market.

From 1880, Arnhold was a member of the Society of Friends. Between 1911 and 1925, he was a member of the Senate of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society.

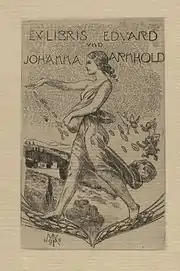

_Eduard_Arnhold.jpg.webp)

_Johanna_Arnhold.jpg.webp)

Arnhold died in 1925 at the age of 76 in Neuhaus am Schliersee. His grave is located at the Friedhof Wannsee, Lindenstraße in Wannsee. He rests there at the side of his wife Johanna Arnhold née Arnthal (1859-1929). In front of the grave wall with inscription plaques is a sculpture by Theodor Georgii depicting a farewell scene.[6] By decision of the Senate of Berlin, the final resting place of Eduard Arnhold (grave location Li AT FW-38) has been dedicated as an honorary grave of the State of Berlin since 1992. The dedication was extended in 2018 for the usual period of twenty years.[7]

References

- Flitter, Emily (2018-08-29). "Henry Arnhold, Patriarch of a Storied Banking Family, Dies at 96". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- "Eduard Arnhold". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- Becker, Peter von (2015-08-08). "Eduard Arnhold: Der Magnat als Mäzen". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). ISSN 1865-2263. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- Kai Drewes: Jüdischer Adel. Nobilitierungen von Juden im Europa des 19. Jahrhunderts. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt 2013, pp 47 f., pp. f.

- "Die Papageien sind unbedenklich - The Parrots Are Unproblematic". www.lootedart.com. Archived from the original on 2016-08-11. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

Max Liebermanns „Papageienallee" aus dem Jahr 1902 etwa, eines der wohl bedeutendsten Stücke der Bremer Kunsthalle, war einst im Besitz des jüdischen Kunstsammlers Eduard Arnhold in Berlin, der es später seiner Tochter Elisabeth vermachte.

- Hans-Jürgen Mende: Lexikon Berliner Begräbnisstätten. Pharus-Plan, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-86514-206-1, p. 659.

- Ehrengrabstätten des Landes Berlin (as of November 2018). (PDF, 413 kB) Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Verkehr und Klimaschutz, p. 2; retrieved 16 February 2021. Anerkennung und weitere Erhaltung von Grabstätten als Ehrengrabstätten des Landes Berlin. (PDF, 369 kB). Abgeordnetenhaus von Berlin, Drucksache 18/14895 vom 21 November 2018, p. 1 und Anlage 2, p. 1; retrieved 16 February 2021.

Further reading

- Johanna Arnhold: Eduard Arnhold. Ein Gedenkbuch. self-published, Berlin 1928.

- Peter von Becker: Eduard Arnhold. Reichtum verpflichtet – Unternehmer und Kunstmäzen. (Jüdische Miniaturen, Band 237.) Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin / Leipzig 2019, ISBN 978-3-95565-321-7.

- Deutsche Akademie Villa Massimo (ed.): Eduard Arnhold. Accademia Tedesca Villa Massimo, Rome 1988.

- Michael Dorrmann: Eduard Arnhold (1849–1925). Eine biographische Studie zu Unternehmer- und Mäzenatentum im Deutschen Kaiserreich. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003748-2.

- Adolf Harnack: Gedächtnisrede bei der Trauerfeier für Herrn Geheimen Kommerzienrat Eduard Arnhold am 15. August 1925. Holten, Berlin 1925.

- Sven Kuhrau: Der Kunstsammler im Kaiserreich. Kunst und Repräsentation in der Berliner Privatsammlerkultur. Ludwig, Kiel 2005, ISBN 3-937719-20-2.

- Dietrich Nummert: Jagd nach Reichtum, Jagd auf Kunst. Kaufmann Eduard Arnhold. In Berlinische Monatsschrift (Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein). Issue 6, 1999, ISSN 0944-5560, pp. 64–69 Portrait on luise-berlin.de).

- Angela Windholz: Villa Massimo. Zur Gründungsgeschichte der Deutschen Akademie in Rom und ihrer Bauten. Michael Imhof, Petersberg 2003, ISBN 3-935590-93-8.

External links

- Literature by and about Eduard Arnhold in the German National Library catalogue

- Eduard Arnhold