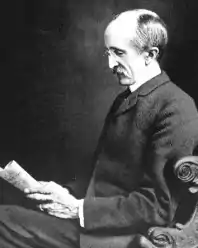

Edward Livingston Trudeau

Edward Livingston Trudeau (October 5, 1848 – November 15, 1915) was an American physician who established the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium at Saranac Lake for treatment of tuberculosis. Dr. Trudeau also established the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis, the first laboratory in the United States dedicated to the study of tuberculosis. He was a public health pioneer who helped to establish principles for disease prevention and control.

Edward Livingston Trudeau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 5, 1848 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | November 15, 1915 (aged 67) Saranac Lake, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Relatives | Garry Trudeau (great-grandson) |

Life and career

Named for statesman Edward Livingston, Trudeau was born in New York City to a family of physicians, the son of Cephise (née Berger) and James de Berty Trudeau, who was descended from Illinois Country Governor Zénon Trudeau.[1] During his late teens, his older brother James contracted tuberculosis and Edward nursed him until his death three months later. At twenty, he enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University (then Columbia College), completing his medical training in 1871.

Trudeau married Lottie Beare in June 1871, and after travelling to Europe the couple settled on Long Island, New York, where Trudeau began his medical practice. Trudeau mentioned Beare in his autobiography and remarked on the fortitude with which she met the many adversities of their married life, which included his tuberculosis, and the deaths of three of their four children. Shortly after settling in their home on Long Island, the couple's first child, Charlotte, whom they called "Chatte", was born.

Trudeau was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1873, shortly before the birth of their second child, Edward Livingston Jr, whom they called Ned. Following conventional thinking of the times, his physicians and friends urged a change of climate. He went to live in the Adirondack Mountains, initially at Paul Smith's Hotel, spending as much time as possible in the open; he subsequently regained his health. In 1876 he moved his family to Saranac Lake and established a medical practice among the sportsmen, guides and lumber camps of the region. In 1877 Lottie gave birth to a third child, Henry, who died after a brief illness in the winter of 1878 or 1879.

In 1882, Trudeau read about Prussian Dr. Hermann Brehmer's success treating tuberculosis with the "rest cure" in cold, clear mountain air. Following this example, Trudeau founded the Adirondack Cottage Sanitorium, with the support of several of the wealthy businessmen he had met at Paul Smiths. In 1894, after a fire destroyed his small laboratory, Trudeau organized the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis with a gift from Elizabeth Milbank Anderson;[1] it was the first laboratory in the United States for the study of tuberculosis. Renamed the Trudeau Institute, the laboratory continues to study infectious diseases. One of Trudeau's early patients was author Robert Louis Stevenson and in gratitude, Stevenson presented Trudeau with a complete set of his works, each one dedicated with a different verse by Stevenson (the books were later lost in a fire at Saranac). Trudeau's fame helped establish Saranac Lake as a center for the treatment of tuberculosis.

A fourth child, Francis B. Trudeau, was born in 1887. Francis later succeeded his father as director of the sanatorium until 1954. Francis was the only one of the four Trudeau children to live a long life. Charlotte (Chatte) contracted tuberculosis at age sixteen while attending a girls school in New York City. She returned home to Saranac Lake where she was nursed by her parents for three years until her death there in 1889. Ned graduated from the Yale College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1900 and began a medical practice in New York City, but died after a bout of pneumonia.

In addition to his work at the sanatorium, Trudeau enjoyed hunting in the woods around Saranac Lake. Although his illness often limited his activities, he enjoyed the outdoors. In later years he had a camp on Upper Saint Regis Lake. Trudeau had many friends and was active in the community, helping to found St. John's in the Wilderness Episcopal Church in Paul Smiths, New York, where he is interred. Edward Livingston Trudeau died in Saranac Lake on November 15, 1915.[2]

Legacy

Trudeau may be viewed as a public health pioneer of the pre-antibiotic era, recognizing the role of crowding in disease transmission, the utility of isolation, and the practice of notifiable disease reporting, and promoting the value of fresh air, exercise, and healthy diet.[3] These principles for disease prevention and control have had enduring global impact. He was chosen to be the first President of the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, founded in June 1904.[4]

The Trudeau Institute, a not-for-profit, biomedical research center, is a direct descendant of the Saranac Laboratory that Trudeau founded. On October 7, 1972, a commemorative plaque was bolted to a rock by the Trudeau Institute on Rabbit Island, located between Spitfire Lake and Upper Saint Regis Lake of Brighton, New York. The plaque honors a historic experiment of Trudeau's in which rabbits were injected with tuberculosis "to determine the effect of environment on the influence and progress" of the disease. Rabbit Island is privately owned and tourists are not encouraged.[5]

On May 12, 2008, the United States Postal Service issued a 76 cent stamp picturing Trudeau, part of the Distinguished Americans series. An inscription identifies him as a "phthisiologist" (an obsolete term for a tuberculosis specialist).

See also

References

- Trudeau, Edward Livingston (1916). An autobiography. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page & Co. Sequence 16, p. 8. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2012 – via Harvard University Library PDS.

- "Tuberculosis Expert Dies". The Indianapolis Star. November 16, 1915. p. 2. Retrieved January 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "T. Mitchell Prudden (New York City) to Edward Livingston Trudeau (Saranac Lake), January 22, 1897". Biographical Sketches and Letters of T. Mitchell Prudden, M.D. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1927. p. 232.

- Rosen, George. "Chapter VIII: Bacteriological Era and Aftermath (Concluded)". A History of Public Health. New York: MD Publications. p. 389.

- "Tuberculin Rabbit Shrine". Roadside America. Retrieved October 25, 2013.