Eel life history

Eels are any of several long, thin, bony fishes of the order Anguilliformes. They have a catadromous life cycle, that is: at different stages of development migrating between inland waterways and the deep ocean. Because fishermen never caught anything they recognized as young eels, the life cycle of the eel was a mystery for a very long period of scientific history that continues into the present day. Of significant interest is the search for the spawning grounds for the various species of eels and identifying impacts to population decline in each stage of the life cycle.

Past studies of eels

The European eel (Anguilla anguilla) was historically the one most familiar to Western scientists, beginning with Aristotle, who wrote the earliest known inquiry into the natural history of eels. He speculated that they were born of "earth worms", which he believed were formed of mud, growing from the "guts of wet soil" rather than through sexual reproduction. Many centuries passed before scientists were able to demonstrate that such spontaneous generation does not occur in nature.

In 1777, the Italian Carlo Mondini located an eel's ovaries and demonstrated that eels are a kind of fish.[1] In 1876, as a young student in Austria, Sigmund Freud dissected hundreds of eels in search of the male sex organs. He had to concede failure in his first major published research paper, and turned to other issues in frustration.[2][3][4][5]

Larval eels — transparent, leaflike two-inch (five-cm) creatures of the open ocean — were not generally recognized as such until 1893; instead, they were thought to be a separate species, Leptocephalus brevirostris (from the Greek leptocephalus meaning "thin- or flat-head"). In 1886, however, the French zoologist Yves Delage discovered the truth when he kept leptocephali alive in a laboratory tank in Roscoff until they matured into eels, and in 1896 Italian zoologist Giovanni Battista Grassi confirmed the finding when he observed the transformation of a Leptocephalus into a round glass eel in the Mediterranean Sea. (He also observed that salt water was necessary to support the maturation process.) Although the connection between larval eels and adult eels is now well understood, the name leptocephalus is still used for larval eel.

Search for the spawning grounds

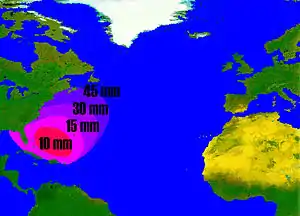

European eel

The Danish professor Johannes Schmidt, beginning in 1904, led a series of expeditions into the Mediterranean Sea and the North Atlantic (the Dana expeditions) to investigate eels. The expeditions were largely financed by the Carlsberg Foundation. He noted that all the leptocephali he found were very similar, and hypothesized that they all must have descended from a common ancestor species. He also observed that the farther out to sea in the Atlantic Ocean he went, the smaller the leptocephali he caught were. In a 1922 expedition, he sailed as far as the Sargasso Sea, south of Bermuda, where he caught the smallest eel-larvae that had ever been seen. Although Schmidt did not directly observe eel spawning, or even find ready-to-spawn adult eels, he was able to deduce the following about the life history of the eel, based on the size distribution of the leptocephali he collected: The larvae of European eels travel with the Gulf Stream across the Atlantic Ocean, and grow to 75–90 mm within one to three years, before they reach the coasts of Europe. Marine eels of the order Anguilliformes also have a leptocephalus stage, and likely pass through a stage similar to the anguillid glass eels, but they are rarely seen in the ocean.

Eels in this so-called "recruitment" developmental stage are known as glass eels because of the transparency of their bodies. The term typically refers to a transparent eel of the family Anguillidae. It is applied to an intermediary stage in the eel's complex life history between the leptocephalus stage and the juvenile (elver) stage. Glass eels are defined as "all developmental stages from completion of leptocephalus metamorphosis until full pigmentation".[6] Once the glass eels arrive at coastal areas, they migrate up rivers and streams, overcoming various natural challenges — sometimes by piling up their bodies by the tens of thousands to climb over obstacles — and they reach even the smallest of creeks. At this stage in their growth they are small enough to benefit from surface tension in order to climb vertical walls.[7]

In fresh water they develop pigmentation, turn into elvers (young eels), and feed on creatures such as small crustaceans, worms, and insects. For 10 to 14 years they mature, growing to a length of 60 to 80 cm. The eels can propel themselves over wet grass and dig through wet sand to reach upstream headwaters and ponds, thus colonizing the continent. During this stage they are called yellow eels because of their golden pigmentation.

In July, some mature individuals migrate back towards the sea, crossing wet grasslands at night to reach rivers that lead to the sea. Eel migration out of their freshwater growth habitats from various parts of Europe, or through the Baltic Sea in the Danish straits, have been the basis of traditional fisheries with characteristic trapnets.

How the adults make the 6,000 km (3,700 mi) open ocean journey back to their spawning grounds north of the Antilles, Haiti, and Puerto Rico remains unknown. By the time they leave the continent, their gut dissolves, making feeding impossible, so they have to rely on stored energy alone.[8] The external features undergo other dramatic changes, as well: the eyes start to enlarge, the eye pigments change for optimal vision in dim blue clear ocean light, and the sides of their bodies turn silvery, to create a countershading pattern which makes them difficult to see by predators during their long open-ocean migration. These migrating eels are typically called "silver eels" or "big eyes".

German fisheries biologist Friedrich Wilhelm Tesch, an eel expert and author, conducted many expeditions with high-tech instrumentation to follow eel migration, first down the Baltic, then along the coasts of Norway and England, but finally the transmitter signals were lost at the continental shelf when the batteries ran out According to Schmidt, a travel speed in the ocean of 15 km per day can be assumed, so a silver eel would need around 140 to 150 days to reach the Sargasso Sea from Scotland and about 165 to 175 days when leaving from the English Channel.

Tesch — like Schmidt — kept trying to persuade sponsors to provide more funding for expeditions. His proposal was to release 50 silver eels from Danish waters, with transmitters that would detach from the eels each second day, float up toward the surface, and broadcast their position, depth, and temperature to satellite receivers. He also suggested that countries on the western side of the Atlantic could perform a similar release experiment at the same time. In December 2018 researchers in the Azores, (about 1,400 km (870 mi) west of the Iberian coast—the furthest point on the migration route identified in previous experiments) fitted 26 large female European eels with satellite tags and released them into the Atlantic Ocean. Tracking demonstrated that the fishes' journey to the Sargasso took a further year, or more.[9]

American eel

Another Atlantic eel species is known: the American eel, Anguilla rostrata. First it was believed European and American eels were the same species due to their similar appearance and behavior, but they differ in chromosome count and various molecular genetic markers, and in the number of vertebrae, A. anguilla counting 110 to 119 and A. rostrata 103 to 110.

The spawning grounds for the two species are in an overlapping area of the southern Sargasso Sea, with A. rostrata apparently being more westward than A. anguilla. This was confirmed in 2023.[10] After spawning in the Sargasso Sea and moving to the west, the leptocephali of the American eel exit the Gulf Stream earlier than the European eel and begin migrating into the estuaries along the east coast of North America between February and late April at an age around one year and a length around 60 mm.

Japanese eel

The spawning area of the Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica, has also been found. Their breeding site is to the west of the Suruga seamount (14–17°N, 142–143°E), near the Mariana Islands.[11] and their leptocephali are then transported to the west to East Asia by the North Equatorial Current.

In June and August 2008, Japanese scientists discovered and caught matured adult eels of A. japonica and A. marmorata in the West Mariana Ridge.[12]

Southern African eels

Southern Africa's four species of freshwater eels (A. mossambica, A. bicolor bicolor, A. bengalensis labiata, and A. marmorata) have an interesting migratory pattern: It takes them on a long journey from their spawning grounds in the Indian Ocean north of Madagascar to high up in some of the Southern African river systems and then back again to the ocean off Madagascar.[13]

New Zealand longfin eels

New Zealand longfin eels breed only once at the end of their lives, making a journey of thousands of kilometres from New Zealand to their spawning grounds near Tonga.[14][15] Their eggs (of which each female eel produces between 1 and 20 million) are fertilized in an unknown manner, but probably in deep tropical water.[16] The mature eels then die, their eggs floating to the surface to hatch into very flat leaf-like larvae (called leptocephalus) that then drift along large oceanic currents back to New Zealand.[14][17] This drifting is thought to take up to 15 months.[16] There have been no recorded captures of either the eggs or larvae of longfin eels.[14]

Decline of the glass eels

No one yet knows the reasons, but beginning in the mid-1980s, glass eel arrival in the spring dropped drastically — in Germany to 10% and in France to 14% of their previous levels — from even conservative estimates. Data from Maine and other North American coasts showed similar declines, although not as drastic.

In 1997, European demand for eels could not be met for the first time ever, and dealers from Asia bought all they could. The traditional European stocking programs could not compete any longer: each week, the price for a kilogram of glass eel went up another US$30. Even before the 1997 generation hit the coasts of Europe, dealers from China alone placed advance orders for more than 250,000 kg, some bidding more than $1,100 per kg. Asian elvers have sold in Hong Kong for as much as $5,000 to $6,000 a kilogram at times when $1,000 would buy the same amount of American glass eels at their catching sites.[18] Such a kilogram, consisting of 5000 glass eels, may bring at least $60,000 and as much as $150,000 after they leave an Asian fish farm. In New Jersey, over 2000 licenses for glass eel catch were issued and reports of 38 kg per night and fisherman have been made, although the average catch is closer to 1 kg.

Glass eels have been harvested for food from the River Severn, England, for centuries, but for about 200 years, from the sixteenth to eighteenth century, the practice was outlawed by act of Parliament.[19] The restriction was removed in 1873 and in 1908 a collection point and holding station for the catch was established at Epney, Gloucestershire. Initially the crop was sold for human consumption but, as infrastructure for live transport improved, the glass eels were exported throughout Europe for stocking natural waterways and to the Far East for eel aquaculture.[20][21]

The demand for adult eels has continued to grow, as of 2003. Germany imported more than $50 million worth of eels in 2002. In Europe, 25 million kg are consumed each year, but in Japan alone, more than 100 million kg were consumed in 1996. As the European eels become less available, worldwide interest in American eels has increased dramatically.

New high-tech eel aquaculture plants are appearing in Asia, with detrimental effects on the native Japanese eel, A. japonica. Traditional eel aquaculture operations rely on wild-caught elvers, but experimental hormone treatments in Japan have led to artificially spawned eels. Eggs from these treated eels have a diameter of about 1 mm, and each female can produce up to 10 million eggs. However, these treated eels may not solve the eel crisis. Scientists are struggling to get eels to sexual maturity without environmental cues.[22] Additionally, leptocephali (larva) require a diet of marine snow which is difficult to recreate in aquaculture.[22]

Threats to eels

Strong concerns exist that the European eel population might be devastated by a new threat: Anguillicola crassus, a foreign parasitic nematode. This parasite from East Asia (the original host is A. japonica) appeared in European eel populations in the early 1980s. Since 1995, it also appeared in the United States (Texas and South Carolina), most likely due to uncontrolled aquaculture eel shipments. In Europe, eel populations are already from 30% to 100% infected with the nematode. Recently, this parasite was shown to inhibit the function of the swimbladder as a hydrostatic organ.[23][24] As open ocean voyagers, eels need the carrying capacity of the swimbladder (which makes up 3–6% of the eel's body weight) to cross the ocean on stored energy alone.

Because the eels are catadromous (living in fresh water but spawning in the sea), dams and other river obstructions can block their ability to reach inland feeding grounds. Since the 1970s, an increasing number of eel ladders have been constructed in North America and Europe to help the fish bypass obstructions.

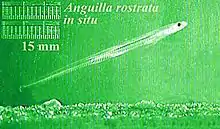

In New Jersey, an ongoing project monitors the glass eel migration with an online in situ microscope. As soon as more funding becomes available, it will be possible to log into the system via a Longterm Ecological Observatory (LEO) site.

See also

References

- Mundine, Carolus (1783). De Angillae Ovariis.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) 6:406-18 - Freud, Sigmund (1877). Beobachtungen über Gestaltung und feineren Bau der als Hoden beschriebenen Lappenorgane des Aals [Observations on the configuration and finer structure of the lobed organs in eels described as testes].

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) Vol. 75, p. 419. Freud's study was in response to Szymon Syrski's book Ueber die Reproductions-Organe der Aale (1874); see Ursula Reidel-Schrewe "Freud's Début in the Sciences" in: Sander L. Gilman, Jutta Birmele, Jay Geller, Valerie D Greenberg (eds.), Reading Freud's Reading, NYU Press, 1995, pp. 1–22. - "Was dachten Nazis über den Aal? | Archiv - Berliner Zeitung" (in German). Berlinonline.de. 2004-10-20. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- FH. "Der Aal im Nationalsozialismus" (in German). Wno.org. Archived from the original on December 17, 2011. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- "Sigmund Freud und der Aal" (in German). Kulturkurier.de. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- Tesh F.W. 2003. The eel, third edition. Published by Blackwell Science. 408 pages

- Safran, Patrick, ed. (2009). Fisheries and aquaculture : towards sustainable aquatic living resources management. Vol. 3. Oxford: UNESCO. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-84826-560-8.

- Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- "Ancient mystery of European eel migration unravelled to help combat decline of critically endangered species". Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- Wright, R.M.; Piper, A.T.; Aarestrup, K. (2023). "First direct evidence of adult European eels migrating to their breeding place in the Sargasso Sea". Scientific Reports. 12. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-19248-8.

- Tsukamoto, Katsumi (23 February 2006). "Spawning of eels near a seamount". Nature. 439 (7079): 929. doi:10.1038/439929a. PMID 16495988. S2CID 4346565.

- Chow, S.; Kurogi, H.; Mochioka, N.; Kaji, S.; Okazaki, M.; Tsukamoto, K. (2009). "Discovery of mature freshwater eels in the open ocean". Fisheries Science. 75: 257–259. doi:10.1007/s12562-008-0017-5. S2CID 39090269.

- Jim Cambray (April 2004). "African freshwater eels - new tools in environmental education". Science in Africa. Archived from the original on 2013-03-17. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

- Jellyman, D.; Tsukamoto, K. (2010). "Vertical migrations may control maturation in migrating female Anguilla dieffenbachii". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 404: 241–247. Bibcode:2010MEPS..404..241J. doi:10.3354/meps08468.

- Jellyman, D. (2006). "Tagging along when longfins go spawning" (PDF). Water & Atmosphere. 14 (1): 24–25.

- McDowall, R. M. (1990). New Zealand freshwater fishes: a natural history and guide (Rev. ed.). Auckland: Heinemann-Reed.

- Chisnall, B. L.; Jellyman, D. J.; Bonnett, M. L.; Sykes, J. R. (2002). "Spatial and temporal variability in length of glass eels (Anguilla spp.) in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 36 (1): 89–104. doi:10.1080/00288330.2002.9517073.

- "Demand for Baby Eels Brings High Prices and Limits". 2000-12-03. Archived from the original on December 24, 2002. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- 25 Henry VIII, c. 7

- 36 & 37 Vict c. 71

- Aprahamian, Miran; Wood, Peter (February 2021). "Estimation of glass eel ( Anguilla anguilla ) exploitation in the Severn Estuary, England". Fisheries Management and Ecology. 28 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1111/fme.12455. S2CID 225134755.

- Bird, Winifred. "In Japan, Captive Breeding May Help Save the Wild Eel". Yale Environment 360. Yale School of the Environment. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Schneebauer, Gabriel; Dirks, Ron P.; Pelster, Bernd (2017-08-17). "Anguillicola crassus infection affects mRNA expression levels in gas gland tissue of European yellow and silver eel". PLOS ONE. 12 (8): e0183128. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1283128S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183128. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5560681. PMID 28817599.

- Würtz, J.; Taraschewski, H. (2000-01-14). "Histopathological changes in the swimbladder wall of the European eel Anguilla anguilla due to infections with Anguillicola crassus". Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 39 (2): 121–134. doi:10.3354/dao039121. ISSN 0177-5103. PMID 10715817.

Sources and further reading

- Banks, R.C., R.W. McDiarmid, A.L. Gardner, & W.C. Starnes (2003). Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada.

- Bussing, W.A. (1998). Peces de las aguas continentales de Costa Rica [Freshwater fishes of Costa Rica]. 2nd ed. San José Costa Rica: Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica.

- Butsch, R.S. (1939). A list of Barbadian fishes. J. B.M.H.S. 7(1): pp. 17–31.

- Böhlke, J.E. & C.C.G. Chaplin (1993). Fishes of the Bahamas and adjacent tropical waters. 2nd edition. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- Claro, R. (1994). Characterísticas generales de la ictiofauna. pp. 55–70. [In] R. Claro [ed.] Ecología de los peces marinos de Cuba. Instituto de Oceanología Academia de Ciencias de Cuba and Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo.

- Claro, Rodolfo, & Lynne R. Parenti (2001). Chapter 2: The Marine Ichthyofauna of Cuba. [In] Claro, Rodolfo, Kenyon C. Lindeman, & L.R. Parenti, [eds.] Ecology of the Marine Fishes of Cuba. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, DC, USA. pp. 21–57. ISBN 1-56098-985-8.

- Erdman, D.S. (1984). Exotic fishes in Puerto Rico. pp. 162–176. [In] W.R. Courtney, Jr. & J.R. Stauffer, Jr. [eds.] Distribution, biology and management of exotic fishes. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, USA.

- Eschmeyer, William N., [ed.] (1998). Catalog of Fishes. Special Publication of the Center for Biodiversity Research and Information, no. 1, vol 1–3. California Academy of Sciences. San Francisco, California, USA. 2905. ISBN 0-940228-47-5.

- Fish, M.P. & W.H. Mowbray (1970). Sounds of Western North Atlantic fishes. A reference file of biological underwater sounds. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (1992). FAO yearbook 1990. Fishery statistics. Catches and landings. FAO Fish. Ser. (38). FAO Stat. Ser. 70:(105)

- Food and Agriculture Organization (1997). Aquaculture production statistics 1986–1995. FAO Fish. Circ. 815, Rev. 9.

- Greenfield, D.W & J.E Thomerson (1997). Fishes of the continental waters of Belize. University Press of Florida, Florida.

- International Game Fish Association (1991). World record game fishes. International Game Fish Association, Florida, USA.

- Jessop, B.M. (1987). Migrating American eels in Nova Scotia. Trans. Amer. Fish. Soc. 116: pp. 161–170.

- Kenny, J.S. (1995). Views from the Bridge: A memoir on the freshwater fishes of Trinidad. Julian S. Kenny, Maracas, St. Joseph, Trinidad, & Tobago.

- Lim, P., Meunier, F.J., Keith, P. & Noël, P.Y. (2002). Atlas des poissons et des crustacés d'eau douce de la Martinique. Patrimoines Naturels, 51: Paris: MNHN.

- Murdy, Edward O., Ray S. Birdsong, & John A. Musick 1997. Fishes of Chesapeake Bay. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, DC, USA. ISBN 1-56098-638-7.

- Nelson, Joseph S., Edwin J. Crossman, Héctor Espinosa-Pérez, Lloyd T. Findley, Carter R. Gilbert, Robert N. Lea, & James D. Williams, [eds.] (2004). Common and scientific names of fishes from the United States, Canada, and Mexico, Sixth Edition. American Fisheries Society Special Publication, no. 29. American Fisheries Society. Bethesda, Maryland, USA. ISBN 1-888569-61-1.

- Nielsen, J.G. and E. Bertelsen (1992). Fisk i grønlandske farvande. Atuakkiorfik, Nuuk. 65 s.

- Nigrelli, R.F. (1959). Longevity of fishes in captivity, with special reference to those kept in the New York Aquarium. pp. 212–230. [In] G.E.W. Wolstehnolmen & M. O'Connor [eds.] Ciba Foundation Colloquium on Ageing: the life span of animals. Vol. 5., Churchill, London.

- Ogden, J.C., J.A. Yntema, & I. Clavijo (1975). An annotated list of the fishes of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands. Spec. Publ. No. 3.

- Page, L.M. & B.M. Burr (1991). A field guide to freshwater fishes of North America north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

- Piper, R. (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- Robins, C.R. & G.C. Ray (1986). A field guide to Atlantic coast fishes of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA

- Robins, Richard C., Reeve M. Bailey, Carl E. Bond, James R. Brooker, Ernest A. Lachner, et al. (1980). A List of Common and Scientific Names of Fishes from the United States and Canada, Fourth Edition. American Fisheries Society Special Publication, no. 12. American Fisheries Society. Bethesda, MD.

- Robins, Richard C., Reeve M. Bailey, Carl E. Bond, James R. Brooker, Ernest A. Lachner, et al. 1980. A List of Common and Scientific Names of Fishes from the United States and Canada, Fourth Edition. American Fisheries Society Special Publication, no. 12. American Fisheries Society. Bethesda, MD.

- Smith, C.L. (1997). National Audubon Society field guide to tropical marine fishes of the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, Florida, the Bahamas, and Bermuda. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, NY.

- Tesch, F.-W. (2003) The eel. Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK.

- Wallace, Karen (1993) Think of an Eel, Walker Books, UK. [A picture book for children that describes the life cycle of the eel.]

- Wenner, C.A. (1978). Anguillidae. [In] W. Fischer [ed.] FAO species identification sheets for fishery purposes. West Atlantic (Fishing Area 31). volume 1. FAO, Rome, IT.

External links

- The Maine Eel and Elver Fishery, Maine Department of Marine Resources

- The Maine Eel and Elver Fishery, archived copy

- Fishbase entry for Anguilla anguilla

- Fishbase entry for Anguilla rostrata

- ICES report about eel stock collapse

- U.K Glass Eels — a large commercial firm's website, with history and fact pages

- Projekt eelBASE

.png.webp)