Eendrachtsland

Eendrachtsland or Eendraghtsland (Dutch: het Landt van d'Eendracht and Land van de Eendracht) is an obsolete geographical name for an area centred on the Gascoyne region of Western Australia. Between 1616 and 1644, during the European age of exploration, Eendraghtsland was also a name for the entire Australian mainland.[1] From 1644, it and the surrounding areas were known as New Holland (and, much later, as Western Australia).[2]

.png.webp)

In 1616, Dirk Hartog, captain of the Dutch East India Company ship Eendracht, encountered the west coast of the Australian mainland, meeting it close to the 26th parallel south latitude (26° south), near what is now known as Dirk Hartog Island in Western Australia.[3]: 119 After leaving the island, the Eendracht sailed in a north-west direction along the coast of the mainland, Hartog charting as he went.[1] He gave this land the name het Landt van d'Eendracht, literally Eendrachtsland, after his ship, the Eendracht (English: "Unity"[1] or "Concord").

Eendrachtsland on the charts

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

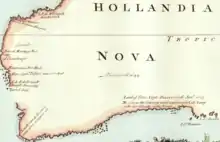

The earliest known appearance of that name on the charts was eleven years later in 1627 on, Caert van't Landt van d'Eendracht ("Chart of the Land of Eendracht"), by Hessel Gerritsz, however the name was in use as early as 1619.[1]

The Caert van't Landt van d'Eendracht images are showing that things were done quite differently in the 1620s as the chart is oriented with north to the left and shows the degrees of latitude on the bottom of the chart.

Eendrachtsland was first revealed to the world in 1626 on the small world map on the title page of the Iournael vande Nassausche Vloot [Journal of the Nassau Fleet]. This was the first published map to show any authentic part of the Australian coastline: it shows t'Eendracht Land as part of a notionally much larger landmass.[3]: 119

T.Lant van Eendracht also appeared on the world map, Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula by Jodocus Hondius II, published in Amsterdam in 1625, and on the world map by Johannes Kepler and Philipp Eckebrecht, Noua Orbis Terrarum Delineatio Singulari Ratione Accommodata Meridiano Tabb. Rudolphi Astronomicarum, composed in 1630 and published in 1658 in Kepler's Rudolphine Tables.[4]

Eendrachtsland coastline knowledge

The chart shows that the knowledge held by the Dutch of the West Australian coastline was increasing, as the chart was based on a number of voyages, beginning with this 1616 voyage of Dirk Hartog.[1]

The 1627 chart, broken here and there by unexplored openings, extends from the Willems River (believed to be the Ashburton River) almost to Albany, Western Australia, spanning the West Australian coastline for a distance of around 1,900 km (1,200 mi). It is worth reproducing here what Heeres wrote in 1899 about the increase of Dutch knowledge of the West Australian coastline, as follows:

From this point [Willems River] then the Eendrachtsland of the old Dutch navigators begins to extend southward. To the question, how far it was held to extend, I answer that in the widest sense of the term ('t Land van Eendracht or the South-land, it reached as far as the South-coast, at all events past the Perth of our day)

[...]

More to southward we find in the chart of 1627 I. d'Edels landt, made in July 1619 by the ships Dordrecht and Amsterdam, commanded by Frederik De Houtman and Jacob Dedel. To the north of Dedelsland the coast is rendered difficult of access by reefs, the so-called (Frederik De) Houtmans-Abrolhos (now known as the Houtman Rocks), also discovered on this occasion. To the south, in about 32° S. Lat. Dedelsland is bounded by the Landt van de Leeuwin, surveyed in 1622. Looking at the coast more closely still, we find in about 29° 30, S. Lat. the name Tortelduyff (Turtle Dove Island), to the south of Houtmans Abrolhos, an addition to the chart dating from about 1624.

[...]

So much for the highly interesting chart of Hessel Gerritsz of the year 1627. If we compare with it the revised edition of the 1618 chart, we are struck by the increase of our forefathers' knowledge of the south-west coast. This revised edition gives the entire coast-line down to the islands of St. François and St. Pieter (133° 30' E. Long. Greenwich), still figuring in the maps of our day: the Land of Pieter Nuyts, discovered by the ship het Gulden Zeepaard in 1627.

[...]

North of Willems rivier, this so-called 1618 chart [with additions] has still another addition, _viz_. G. F. De Witsland, discovered in 1628 by the ship Vianen commanded by G. F. De Witt.[1]

Breaks in the Eendrachtsland coast

By the mid to late 1620s the Dutch had gathered a good deal of information, enabling them to chart the west coast of what had become known by then as Eendrachtsland with some accuracy. Heeres then goes on to say that the coastline showed breaks in various places, due to unexplored openings such as Exmouth Gulf.[1] These gaps are clearly visible on the full sized 1627 chart image.

De Witt's land is not connected with the coast of Willems-rivier; the coast-line of Eendrachtsland does not run on; there is uncertainty as regards what is now called Shark-bay; the coast facing Houtmans Abrolhos is a conjectural one only; the coast-line facing Tortelduyf is even altogether wanting; Dedelsland and 't Land van de Leeuwin are not marked by unbroken lines.[1]

True nature of Eendrachtsland

Heeres then suggests that the mid seventeenth century navigators were constantly faced by the problem of the true character of this South-land, asking themselves the question:

...was it one vast continent or a complex of islands? And the question would not have been so repeatedly asked, if the line of the west-coast had been more accurately known.[1]

End of Eendrachtsland

By 1644 most of these problems of gaps in the coastline were solved, spelling the end of the name Eendrachtsland, in favour of a name, which for the Dutch, was much closer to the heart.

Tasman and Visscher did a great deal towards the solution of this problem, since in their voyage of 1644 they also skirted and mapped out the entire line of the West-coast of what since 1644 has borne the name of Nieuw-Nederland, Nova Hollandia, or New Holland, [charting] from Bathurst Island to a point south of the Tropic of Capricorn.[1]

References

- Jan Ernst Heeres LL. D. Professor at the Dutch Colonial Institute Delft. The Part Borne by the Dutch in the Discovery of Australia 1606-1765 (txt) (A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook - Latin-1(ISO-8859-1)--8 bit) (1 ed.). 46 Great Russell Street W. C.: The Royal Dutch Geographical Society in Commemoration of the XXVth Anniversary of its Foundation. 0501231.txt. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - After 1770, the entire east coast of Australia became known by as New South Wales. However, the Colony of New South Wales never officially included the western half of Australia, which was known as New Holland, until 1832, when the Colony of Western Australia was proclaimed.

- Van Mourik, Justine (2013). "Hartog's Discovery". In Pool, David (ed.). Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia. ISBN 0642278091. OCLC 50401968.

- Robert J. King, “Johannes Kepler and Australia”, The Globe, no.90, 2021, pp.15-24.