Electrical substation

A substation is a part of an electrical generation, transmission, and distribution system. Substations transform voltage from high to low, or the reverse, or perform any of several other important functions. Between the generating station and consumer, electric power may flow through several substations at different voltage levels. A substation may include transformers to change voltage levels between high transmission voltages and lower distribution voltages, or at the interconnection of two different transmission voltages. They are a common component of the infrastructure. There are 55,000 substations in the United States.[2]

.PNG.webp)

- Primary power lines' side

- Secondary power lines' side

- Primary power lines

- Ground wire

- Overhead lines

- Transformer for measurement of electric voltage

- Disconnect switch

- Circuit breaker

- Current transformer

- Lightning arrester

- Main transformer

- Control building

- Security fence

- Secondary power lines

Substations may be owned and operated by an electrical utility, or may be owned by a large industrial or commercial customer. Generally substations are unattended, relying on SCADA for remote supervision and control.

The word substation comes from the days before the distribution system became a grid. As central generation stations became larger, smaller generating plants were converted to distribution stations, receiving their energy supply from a larger plant instead of using their own generators. The first substations were connected to only one power station, where the generators were housed, and were subsidiaries of that power station.

Types

Substations may be described by their voltage class, their applications within the power system, the method used to insulate most connections, and by the style and materials of the structures used. These categories are not disjointed; for example, to solve a particular problem, a transmission substation may include significant distribution functions.

Transmission substation

A transmission substation connects two or more transmission lines.[3] The simplest case is where all transmission lines have the same voltage. In such cases, substation contains high-voltage switches that allow lines to be connected or isolated for fault clearance or maintenance. A transmission station may have transformers to convert between two transmission voltages, voltage control/power factor correction devices such as capacitors, reactors or static VAR compensators and equipment such as phase shifting transformers to control power flow between two adjacent power systems.

Transmission substations can range from simple to complex. A small "switching station" may be little more than a bus plus some circuit breakers. The largest transmission substations can cover a large area (several acres/hectares) with multiple voltage levels, many circuit breakers, and a large amount of protection and control equipment (voltage and current transformers, relays and SCADA systems). Modern substations may be implemented using international standards such as IEC Standard 61850.

Distribution substation

A distribution substation transfers power from the transmission system to the distribution system of an area.[3] It is uneconomical to directly connect electricity consumers to the main transmission network, unless they use large amounts of power, so the distribution station reduces voltage to a level suitable for local distribution.

The input for a distribution substation is typically at least two transmission or sub-transmission lines. Input voltage may be, for example, 115 kV, or whatever is common in the area. The output is a number of feeders. Distribution voltages are typically medium voltage, between 2.4 kV and 33 kV, depending on the size of the area served and the practices of the local utility. The feeders run along streets overhead (or underground, in some cases) and power the distribution transformers at or near the customer premises.

In addition to transforming voltage, distribution substations also isolate faults in either the transmission or distribution systems. Distribution substations are typically the points of voltage regulation, although on long distribution circuits (of several miles/kilometers), voltage regulation equipment may also be installed along the line.

The downtown areas of large cities feature complicated distribution substations, with high-voltage switching, and switching and backup systems on the low-voltage side. More typical distribution substations have a switch, one transformer, and minimal facilities on the low-voltage side.

Collector substation

In distributed generation projects such as a wind farm or photovoltaic power station, a collector substation may be required. It resembles a distribution substation although power flow is in the opposite direction, from many wind turbines or inverters up into the transmission grid. Usually for economy of construction the collector system operates around 35 kV, although some collector systems are 12 kV, and the collector substation steps up voltage to a transmission voltage for the grid. The collector substation can also provide power factor correction if it is needed, metering, and control of the wind farm. In some special cases a collector substation can also contain an HVDC converter station.

Collector substations also exist where multiple thermal or hydroelectric power plants of comparable output power are in proximity. Examples for such substations are Brauweiler in Germany and Hradec in the Czech Republic, where power is collected from nearby lignite-fired power plants. If no transformers are required for increasing the voltage to transmission level, the substation is a switching station.

Converter substations

Converter substations may be associated with HVDC converter plants, traction current, or interconnected non-synchronous networks. These stations contain power electronic devices to change the frequency of current, or else convert from alternating to direct current or the reverse. Formerly rotary converters changed frequency to interconnect two systems; nowadays such substations are rare.

Switching station

A switching station is a substation without transformers and operating only at a single voltage level. Switching stations are sometimes used as collector and distribution stations. Sometimes they are used for switching the current to back-up lines or for parallelizing circuits in case of failure. An example is the switching stations for the HVDC Inga–Shaba transmission line.

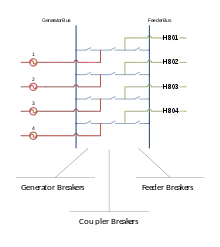

A switching station may also be known as a switchyard, and these are commonly located directly adjacent to or nearby a power station. In this case the generators from the power station supply their power into the yard onto the generator bus on one side of the yard, and the transmission lines take their power from a Feeder Bus on the other side of the yard.

An important function performed by a substation is switching, which is the connecting and disconnecting of transmission lines or other components to and from the system. Switching events may be planned or unplanned. A transmission line or other component may need to be de-energized for maintenance or for new construction, for example, adding or removing a transmission line or a transformer. To maintain reliability of supply, companies aim at keeping the system up and running while performing maintenance. All work to be performed, from routine testing to adding entirely new substations, should be done while keeping the whole system running.

Switchyard at Grand Coulee Dam, United States, 2006. This is a 500 kV switchyard.

Switchyard at Grand Coulee Dam, United States, 2006. This is a 500 kV switchyard. Former high-voltage substation in Stuttgart, Germany, now 110 kV switching station. The 220 kV level is eliminated for grid simplification.

Former high-voltage substation in Stuttgart, Germany, now 110 kV switching station. The 220 kV level is eliminated for grid simplification.

Unplanned switching events are caused by a fault in a transmission line or any other component, for example:

The function of the switching station is to isolate the faulty portion of the system in the shortest possible time. De-energizing faulty equipment protects it from further damage, and isolating a fault helps keep the rest of the electrical grid operating with stability.[5]

Railways

Electrified railways also use substations, often distribution substations. In some cases a conversion of the current type takes place, commonly with rectifiers for direct current (DC) trains, or rotary converters for trains using alternating current (AC) at frequencies other than that of the public grid. Sometimes they are also transmission substations or collector substations if the railway network also operates its own grid and generators to supply the other stations.

Mobile substation

A mobile substation is a substation on wheels, containing a transformer, breakers and buswork mounted on a self-contained semi-trailer, meant to be pulled by a truck. They are designed to be compact for travel on public roads, and are used for temporary backup in times of natural disaster or war. Mobile substations are usually rated much lower than permanent installations, and may be built in several units to meet road travel limitations.[6]

Design

.jpg.webp)

Elements of a substation

Substations generally have switching, protection and control equipment, and transformers. In a large substation, circuit breakers are used to interrupt any short circuits or overload currents that may occur on the network. Smaller distribution stations may use recloser circuit breakers or fuses for protection of distribution circuits. Substations themselves do not usually have generators, although a power plant may have a substation nearby. Other devices such as capacitors, voltage regulators, and reactors may also be located at a substation.

Substations may be on the surface in fenced enclosures, underground, or special-purpose buildings. High-rise buildings may have several indoor substations. Indoor substations are usually found in urban areas to reduce the noise from transformers, improve appearance, or protect switchgear from extreme climate or pollution.

A grounding (earthing) system must be designed. The total ground potential rise and the gradients in potential during a fault (called touch and step potentials) [7] must be calculated to protect passersby during a short circuit in the transmission system. Earth faults at a substation can cause a ground potential rise. Currents flowing in the Earth's surface during a fault can cause metal objects to have a significantly different voltage than the ground under a person's feet; this touch potential presents a hazard of electrocution. Where a substation has a metallic fence, it must be properly grounded to protect people from this hazard.

The main issues facing a power engineer are reliability and cost. A good design attempts to strike a balance between them to achieve reliability without excessive cost. The design should also allow expansion of the station.[8]

Location selection

Selection of the location of a substation must consider many factors. Sufficient land area is required for installation of equipment with necessary clearances for electrical safety, and for access to maintain large apparatus such as transformers.

Where land is costly, such as in urban areas, gas insulated switchgear may save money overall. Substations located in coastal areas affected by flooding and tropical storms may often require an elevated structure to keep equipment sensitive to surges hardened against these elements.[9] The site must have room for expansion due to load growth or planned transmission additions. Environmental effects of the substation must be considered, such as drainage, noise and road traffic effects.

The substation site must be reasonably central to the distribution area to be served. The site must be secure from intrusion by passers-by, both to protect people from injury by electric shock or arcs, and to protect the electrical system from misoperation due to vandalism.

If not owned and operated by a utility company, substations are typically occupied on a long lease such as a renewable 99-year lease, giving the utility company security of tenure.[10]

Design diagrams

The first step in planning a substation layout is the preparation of a one-line diagram, which shows in simplified form the switching and protection arrangement required, as well as the incoming supply lines and outgoing feeders or transmission lines. It is a usual practice by many electrical utilities to prepare one-line diagrams with principal elements (lines, switches, circuit breakers, transformers) arranged on the page similarly to the way the apparatus would be laid out in the actual station.[3]

In a common design, incoming lines have a disconnect switch and a circuit breaker. In some cases, the lines will not have both, with either a switch or a circuit breaker being all that is considered necessary. A disconnect switch is used to provide isolation, since it cannot interrupt load current. A circuit breaker is used as a protection device to interrupt fault currents automatically, and may be used to switch loads on and off, or to cut off a line when power is flowing in the 'wrong' direction. When a large fault current flows through the circuit breaker, this is detected through the use of current transformers. The magnitude of the current transformer outputs may be used to trip the circuit breaker resulting in a disconnection of the load supplied by the circuit break from the feeding point. This seeks to isolate the fault point from the rest of the system, and allow the rest of the system to continue operating with minimal impact. Both switches and circuit breakers may be operated locally (within the substation) or remotely from a supervisory control center.

With overhead transmission lines, the propagation of lightning and switching surges can cause insulation failures into substation equipment. Line entrance surge arrestors are used to protect substation equipment accordingly. Insulation Coordination studies are carried out extensively to ensure equipment failure (and associated outages) is minimal.

Once past the switching components, the lines of a given voltage connect to one or more buses. These are sets of busbars, usually in multiples of three, since three-phase electrical power distribution is largely universal around the world.

The arrangement of switches, circuit breakers, and buses used affects the cost and reliability of the substation. For important substations a ring bus, double bus, or so-called "breaker and a half" setup can be used, so that the failure of any one circuit breaker does not interrupt power to other circuits, and so that parts of the substation may be de-energized for maintenance and repairs. Substations feeding only a single industrial load may have minimal switching provisions, especially for small installations.[8]

Once having established buses for the various voltage levels, transformers may be connected between the voltage levels. These will again have a circuit breaker, much like transmission lines, in case a transformer has a fault (commonly called a "short circuit").

Along with this, a substation always has control circuitry needed to command the various circuit breakers to open in case of the failure of some component.

Automation

Early electrical substations required manual switching or adjustment of equipment, and manual collection of data for load, energy consumption, and abnormal events. As the complexity of distribution networks grew, it became economically necessary to automate supervision and control of substations from a centrally attended point, to allow overall coordination in case of emergencies and to reduce operating costs. Early efforts to remote control substations used dedicated communication wires, often run alongside power circuits. Power-line carrier, microwave radio, fiber optic cables as well as dedicated wired remote control circuits have all been applied to Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) for substations. The development of the microprocessor made for an exponential increase in the number of points that could be economically controlled and monitored. Today, standardized communication protocols such as DNP3, IEC 61850 and Modbus, to list a few, are used to allow multiple intelligent electronic devices to communicate with each other and supervisory control centers. Distributed automatic control at substations is one element of the so-called smart grid.

Insulation

Switches, circuit breakers, transformers and other apparatus may be interconnected by air-insulated bare conductors strung on support structures. The air space required increases with system voltage and with the lightning surge voltage rating. For medium-voltage distribution substations, metal-enclosed switchgear may be used and no live conductors exposed to the environment at all. For higher voltages, gas-insulated switchgear, in a gas insulated substation (GIS) reduces the space required around live buses. Instead of bare conductors, buses and apparatus such as switchgear are built into pressurized tubular containers filled with sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), or an alternative gas. This gas has a higher insulating value than air, allowing the dimensions of the apparatus to be reduced. In addition to air or SF6 gas, apparatus will use other insulation materials such as transformer oil, paper, porcelain, and polymer insulators.

Structure

Outdoor, above-ground substation structures include wood pole, lattice metal tower, and tubular metal structures, although other variants are available. Where space is plentiful and appearance of the station is not a factor, steel lattice towers provide low-cost supports for transmission lines and apparatus. Low-profile substations may be specified in suburban areas where appearance is more critical. Indoor substations may be gas insulated substations (GIS) (at high voltages, with gas insulated switchgear), or use metal-enclosed or metal-clad switchgear at lower voltages. Urban and suburban indoor substations may be finished on the outside so as to blend in with other buildings in the area.

A compact substation is generally an outdoor substation built in a metal enclosure, in which each item of the electrical equipment is located very near to each other to create a relatively smaller footprint size of the substation.

See also

References

- "Joint Consultation Paper: Western Metropolitan Melbourne Transmission Connection and Subtransmission Capacity". Jemena. Powercor Australia, Jemena, Australian Energy Market Operator. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Anguiano, Dani (10 December 2022). "Attacks on Pacific north-west power stations raise fears for US electric grid". The Guardian. Los Angeles. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- Stockton, Blaine. "Design Guide for Rural Substations" (PDF). USDA Rural Development. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Steinberg, Neil (13 December 2013). "Lights On but Nobody Home: Behind the Fake Buildings that Power Chicago". Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- "Transformer Fire Video". metacafe. User Eagle Eye. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Boyd, Dan; Rampaul, Glen. "Mobile Substations" (PDF). IEEE Winnipeg PES Chapter. IEEE Power and Energy Society. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- John, Alvin. "EE35T – Substation Design and Layout". The University Of The West Indies at St. Augustine, Trinidad And Tobago. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Donald G. Fink, H. Wayne Beatty Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers Eleventh Edition, McGraw Hill 1978 ISBN 0-07-020974-X Chapter 17 Substation Design

- Baker, Joseph W. "Eliminating Hurricane Induced Storm Surge Damage To Electric Utilities Via In-place Elevation Of Substation Structures And Equipment" (PDF). DIS-TRAN Packaged Substations. Crest Industries. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Chapman, A. and Broom, R., Electricity Substation Leases: Considerations for Utility Companies, Landowners and Developers, Squire Patton Boggs, originally published by Utility Week, 26 January 2018, accessed 22 August 2023

Further reading

R. M. S. de Oliveira and C. L. S. S. Sobrinho (2009). "Computational Environment for Simulating Lightning Strokes in a Power Substation by Finite-Difference Time-Domain Method". IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility. 51 (4): 995–1000. doi:10.1109/TEMC.2009.2028879.