Electron affinity

The electron affinity (Eea) of an atom or molecule is defined as the amount of energy released when an electron attaches to a neutral atom or molecule in the gaseous state to form an anion.

- X(g) + e− → X−(g) + energy

This differs by sign from the energy change of electron capture ionization.[1] The electron affinity is positive when energy is released on electron capture.

In solid state physics, the electron affinity for a surface is defined somewhat differently (see below).

Measurement and use of electron affinity

This property is used to measure atoms and molecules in the gaseous state only, since in a solid or liquid state their energy levels would be changed by contact with other atoms or molecules.

A list of the electron affinities was used by Robert S. Mulliken to develop an electronegativity scale for atoms, equal to the average of the electrons affinity and ionization potential.[2][3] Other theoretical concepts that use electron affinity include electronic chemical potential and chemical hardness. Another example, a molecule or atom that has a more positive value of electron affinity than another is often called an electron acceptor and the less positive an electron donor. Together they may undergo charge-transfer reactions.

Sign convention

To use electron affinities properly, it is essential to keep track of sign. For any reaction that releases energy, the change ΔE in total energy has a negative value and the reaction is called an exothermic process. Electron capture for almost all non-noble gas atoms involves the release of energy[4] and thus is exothermic. The positive values that are listed in tables of Eea are amounts or magnitudes. It is the word "released" within the definition "energy released" that supplies the negative sign to ΔE. Confusion arises in mistaking Eea for a change in energy, ΔE, in which case the positive values listed in tables would be for an endo- not exo-thermic process. The relation between the two is Eea = −ΔE(attach).

However, if the value assigned to Eea is negative, the negative sign implies a reversal of direction, and energy is required to attach an electron. In this case, the electron capture is an endothermic process and the relationship, Eea = −ΔE(attach) is still valid. Negative values typically arise for the capture of a second electron, but also for the nitrogen atom.

The usual expression for calculating Eea when an electron is attached is

- Eea = (Einitial − Efinal)attach = −ΔE(attach)

This expression does follow the convention ΔX = X(final) − X(initial) since −ΔE = −(E(final) − E(initial)) = E(initial) − E(final).

Equivalently, electron affinity can also be defined as the amount of energy required to detach an electron from the atom while it holds a single-excess-electron thus making the atom a negative ion,[1] i.e. the energy change for the process

- X− → X + e−

If the same table is employed for the forward and reverse reactions, without switching signs, care must be taken to apply the correct definition to the corresponding direction, attachment (release) or detachment (require). Since almost all detachments (require +) an amount of energy listed on the table, those detachment reactions are endothermic, or ΔE(detach) > 0.

- Eea = (Efinal − Einitial)detach = ΔE(detach) = −ΔE(attach).

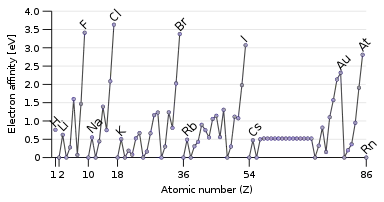

Electron affinities of the elements

Although Eea varies greatly across the periodic table, some patterns emerge. Generally, nonmetals have more positive Eea than metals. Atoms whose anions are more stable than neutral atoms have a greater Eea. Chlorine most strongly attracts extra electrons; neon most weakly attracts an extra electron. The electron affinities of the noble gases have not been conclusively measured, so they may or may not have slightly negative values.

Eea generally increases across a period (row) in the periodic table prior to reaching group 18. This is caused by the filling of the valence shell of the atom; a group 17 atom releases more energy than a group 1 atom on gaining an electron because it obtains a filled valence shell and therefore is more stable. In group 18, the valence shell is full, meaning that added electrons are unstable, tending to be ejected very quickly.

Counterintuitively, Eea does not decrease when progressing down most columns of the periodic table. For example, Eea actually increases consistently on descending the column for the group 2 data. Thus, electron affinity follows the same "left-right" trend as electronegativity, but not the "up-down" trend.

The following data are quoted in kJ/mol.

| Group → | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ Period | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H 73 | He(−50) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li60 | Be(−50) | B 27 | C 122 | N −7 | O 141 | F 328 | Ne(−120) | |||||||||||||

| 3 | Na53 | Mg(−40) | Al42 | Si134 | P 72 | S 200 | Cl349 | Ar(−96) | |||||||||||||

| 4 | K 48 | Ca2 | Sc18 | Ti7 | V 51 | Cr65 | Mn(−50) | Fe15 | Co64 | Ni112 | Cu119 | Zn(−60) | Ga29 | Ge119 | As78 | Se195 | Br325 | Kr(−96) | |||

| 5 | Rb47 | Sr5 | Y 30 | Zr42 | Nb89 | Mo72 | Tc(53) | Ru(101) | Rh110 | Pd54 | Ag126 | Cd(−70) | In37 | Sn107 | Sb101 | Te190 | I 295 | Xe(−80) | |||

| 6 | Cs46 | Ba14 | Lu23 | Hf17 | Ta31 | W 79 | Re6 | Os104 | Ir151 | Pt205 | Au223 | Hg(−50) | Tl31 | Pb34 | Bi91 | Po(136) | At233 | Rn(−70) | |||

| 7 | Fr(47) | Ra(10) | Lr(−30) | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg(151) | Cn(<0) | Nh(67) | Fl(<0) | Mc(35) | Lv(75) | Ts(166) | Og(8) | |||

| La54 | Ce55 | Pr11 | Nd9 | Pm(12) | Sm(16) | Eu11 | Gd(13) | Tb13 | Dy1 | Ho(33) | Er(30) | Tm99 | Yb(−2) | ||||||||

| Ac(34) | Th(113) | Pa(53) | U (51) | Np(46) | Pu(−48) | Am(10) | Cm(27) | Bk(−165) | Cf(−97) | Es(−29) | Fm(34) | Md(94) | No(−223) | ||||||||

| Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Values are in kJ/mol, rounded | |||||||||||||||||||||

| For the equivalent in eV, see: Electron affinity (data page) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Parentheses or Round brackets() denote predictions | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Primordial From decay Synthetic Border shows natural occurrence of the element | |||||||||||||||||||||

Molecular electron affinities

The electron affinity of molecules is a complicated function of their electronic structure. For instance the electron affinity for benzene is negative, as is that of naphthalene, while those of anthracene, phenanthrene and pyrene are positive. In silico experiments show that the electron affinity of hexacyanobenzene surpasses that of fullerene.[5]

"Electron affinity" as defined in solid state physics

In the field of solid state physics, the electron affinity is defined differently than in chemistry and atomic physics. For a semiconductor-vacuum interface (that is, the surface of a semiconductor), electron affinity, typically denoted by EEA or χ, is defined as the energy obtained by moving an electron from the vacuum just outside the semiconductor to the bottom of the conduction band just inside the semiconductor:[6]

In an intrinsic semiconductor at absolute zero, this concept is functionally analogous to the chemistry definition of electron affinity, since an added electron will spontaneously go to the bottom of the conduction band. At nonzero temperature, and for other materials (metals, semimetals, heavily doped semiconductors), the analogy does not hold since an added electron will instead go to the Fermi level on average. In any case, the value of the electron affinity of a solid substance is very different from the chemistry and atomic physics electron affinity value for an atom of the same substance in gas phase. For example, a silicon crystal surface has electron affinity 4.05 eV, whereas an isolated silicon atom has electron affinity 1.39 eV.

The electron affinity of a surface is closely related to, but distinct from, its work function. The work function is the thermodynamic work that can be obtained by reversibly and isothermally removing an electron from the material to vacuum; this thermodynamic electron goes to the Fermi level on average, not the conduction band edge: . While the work function of a semiconductor can be changed by doping, the electron affinity ideally does not change with doping and so it is closer to being a material constant. However, like work function the electron affinity does depend on the surface termination (crystal face, surface chemistry, etc.) and is strictly a surface property.

In semiconductor physics, the primary use of the electron affinity is not actually in the analysis of semiconductor–vacuum surfaces, but rather in heuristic electron affinity rules for estimating the band bending that occurs at the interface of two materials, in particular metal–semiconductor junctions and semiconductor heterojunctions.

In certain circumstances, the electron affinity may become negative.[7] Often negative electron affinity is desired to obtain efficient cathodes that can supply electrons to the vacuum with little energy loss. The observed electron yield as a function of various parameters such as bias voltage or illumination conditions can be used to describe these structures with band diagrams in which the electron affinity is one parameter. For one illustration of the apparent effect of surface termination on electron emission, see Figure 3 in Marchywka Effect.

See also

- Electron-capture mass spectrometry

- Electronegativity

- Electron donor

- Ionization energy — a closely related concept describing the energy required to remove an electron from a neutral atom or molecule

- One-electron reduction

- Valence electron

- Vacuum level

References

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Electron affinity". doi:10.1351/goldbook.E01977

- Robert S. Mulliken, Journal of Chemical Physics, 1934, 2, 782.

- Modern Physical Organic Chemistry, Eric V. Anslyn and Dennis A. Dougherty, University Science Books, 2006, ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3

- Chemical Principles the Quest for Insight, Peter Atkins and Loretta Jones, Freeman, New York, 2010 ISBN 978-1-4292-1955-6

- Remarkable electron accepting properties of the simplest benzenoid cyanocarbons: hexacyanobenzene, octacyanonaphthalene and decacyanoanthracene Xiuhui Zhang, Qianshu Li, Justin B. Ingels, Andrew C. Simmonett, Steven E. Wheeler, Yaoming Xie, R. Bruce King, Henry F. Schaefer III and F. Albert Cotton Chemical Communications, 2006, 758–760 Abstract

- Tung, Raymond T. "Free Surfaces of Semiconductors". Brooklyn College.

- Himpsel, F.; Knapp, J.; Vanvechten, J.; Eastman, D. (1979). "Quantum photoyield of diamond(111)—A stable negative-affinity emitter". Physical Review B. 20 (2): 624. Bibcode:1979PhRvB..20..624H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.20.624.

- Tro, Nivaldo J. (2008). Chemistry: A Molecular Approach (2nd Edn.). New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-100065-9. pp. 348–349.

External links

- Electron affinity, definition from the IUPAC Gold Book