Navan Fort

Navan Fort (Old Irish: Emain Macha Old Irish pronunciation: [ˈeṽənʲ ˈṽaxə]; Modern Irish: Eamhain Mhacha Irish pronunciation: [ˌəunʲ ˈwaxə]) is an ancient ceremonial monument near Armagh, Northern Ireland. According to tradition it was one of the great royal sites of pre-Christian Gaelic Ireland and the capital of the Ulaidh. It is a large circular hilltop enclosure—marked by a bank and ditch—inside which is a circular mound and the remains of a ring barrow. Archeological investigations show that there were once buildings on the site, including a huge roundhouse-like structure that has been likened to a temple. In a ritual act, this timber structure was filled with stones, deliberately burnt down and then covered with earth to create the mound which stands today. It is believed that Navan was a pagan ceremonial site and was regarded as a sacred space. It features prominently in Irish mythology, especially in the tales of the Ulster Cycle. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, "the [Eamhain Mhacha] of myth and legend is a far grander and mysterious place than archeological excavation supports".[1]

Navan Fort or Eamhain Mhacha | |

Location of the site in Northern Ireland | |

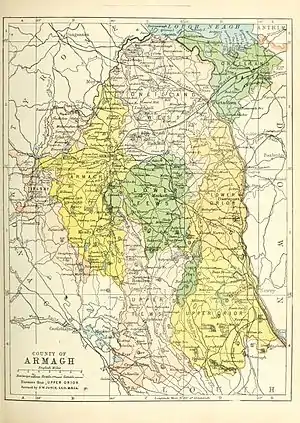

| Location | County Armagh, Northern Ireland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 54°20′53″N 6°41′50″W |

Navan Fort is the heart of the larger 'Navan complex', which also includes the ancient sites of Haughey's Fort (an earlier hilltop enclosure), the King's Stables (a manmade ritual pool) and Loughnashade (a natural lake that has yielded votive offerings).

The name Eamhain Mhacha has been interpreted as "Macha's twins" or "Macha's brooch", referring to a local goddess. 'Navan' is an anglicisation of the Irish An Eamhain.

Name

The Irish name of Navan Fort is Eamhain Mhacha, from Old Irish: Emain Macha. The second element refers to the goddess Macha, for whom nearby Armagh (Ard Mhacha) is also named. However, the overall meaning of the name is unclear. It has been interpreted as "Macha's twins" or "Macha's pair" (possibly referring to the two features on the hilltop, or to Navan Fort and another nearby monument),[2] or as "Macha's brooch" (possibly referring to the shape of the monument). There are tales that try to explain how the name came about. In the second century AD, Greek geographer Ptolemy noted a place called Isamnion somewhere in southeastern Ulster. Some scholars believe this refers to Emain, and Gregory Toner has derived it from Proto-Celtic *isa-mon ("holy mound"). Others believe it refers to a place on the coast.[3]

Eamhain Mhacha, and its short form An Eamhain, was anglicised as 'Owenmagh', 'Nawan' and eventually 'Navan'.[4]

Description

Navan Fort, sometimes called Navan Rath, is a State Care Historic Monument in the townland of Navan. It is on a low hill about 1.6 miles (2.6 km) west of Armagh (at grid ref. area H847 452).[5] The site consists of a circular enclosure 250 metres (820 feet) in diameter, marked by a large bank and ditch encircling the hill. The ditch is on the inside, suggesting the earthwork was symbolic rather than defensive. Inside the enclosure two monuments are visible. North-west of centre is an earthen mound 40 metres (130 feet) in diameter and 6 metres (20 feet) high. South-east of centre is the circular impression of a ring-barrow, about 30 metres (98 feet) in diameter.

Construction and early history

.JPG.webp)

Flint tools and shards of pottery show activity at the site in the Neolithic (c. 4000 to 2500 BC).[7]

In the eighth century BC (Bronze Age), a ring of timber poles was raised at the western site, where the high mound now stands. It was 35m in diameter and surrounded by a ring ditch with an eastern entrance.[7] This ditch was 45 metres (148 feet) in diameter, 5 metres (16 feet) wide and 1 metre (3.3 feet) deep. In the fourth century BC (Iron Age) a new wooden structure was built on the same spot. It was a round building attached to a bigger round enclosure, making a figure-of-eight shape, both with eastern entrances. The larger ring of the figure-of-eight was 30 metres (98 feet) in diameter, the smaller about 20 metres (66 feet). The smaller building had a hearth. The structure has been interpreted as a roundhouse with an attached yard or pen, or a building with an attached enclosure for rituals. Finds suggest that at this time the site was occupied by someone of high standing such as a king, chieftain or druid.[7] They include a chape, a finely-decorated pin and the skull of a Barbary monkey, which was likely a pet that was either imported or given as a gift.[8] The structure was rebuilt several times over the following centuries.[7]

In the first century BC, a huge timber roundhouse-like structure was built on the same spot. It was 40 metres in diameter and consisted of an outer wall and four inner rings of posts (probably holding up a roof), which circled a huge central pillar.[7] This oak pillar has been dated by dendrochronology to the year 95 BC: 61 and could have stood about 13 metres tall.[9] The building had a western entrance, toward the setting sun, which suggests it was not a dwelling. A ditch and bank were dug around it. There is evidence that the huge ditch and bank that encircles the hill was dug at about the same time.[10]

Not long after it was built, the building was filled with thousands of stones, to a height of nearly 3 metres.[7] This stone cairn was flat-topped and split into wedges, resembling a spoked wheel when seen from above. There is some evidence that the stones came from an older monument in the area, perhaps a passage tomb.[11] The building was then deliberately burnt down before being covered in a mound of earth. It was made up of many soil types, suggesting that soil was brought from surrounding areas.[11] There is archaeological evidence for similar repeated building and burning at Tara and Dún Ailinne.: 24–25

In the first or second century BC, a figure-of-eight structure was also built at the eastern site. It was similar to those at the western site and may have been built around the same time as the mound.[12] The larger ring was 30 metres (98 feet) in diameter, the smaller about 20 metres (66 feet). This figure-of-eight structure was then cleared away and replaced by another round wooden structure. It was double-walled, had a central hearth and an eastern entrance. Two graves were found just outside the entrance. This structure was in turn replaced by a ring-barrow: a round mound, usually raised over a burial, surrounded by a ditch and bank.[7]

Purpose

It is believed that the creation of the mound was a ritual act, but its meaning is unclear and there are several theories. The timber building may have been built only as a temporary structure to be burned, or it may have briefly served as a temple before its ritual destruction.[10] Scholars suggest that the event was a sacrificial offering to the gods and that the structure was symbolically given to the Otherworld by being ritually burned and buried. Dr Chris Lynn has likened it to the 'wicker man' rite allegedly carried out by the Gauls, in which a large wooden effigy is burned with a living sacrifice inside.[7][11] It is thought that the huge outer bank and ditch was made to mark out the hilltop as a sacred space. It could also have been seen as a way of containing the power of the Otherworld within that space.[13]

Dr Richard Warner suggests that the mound was made to be a conduit between this world and the Otherworld.[13] It may be an attempt to replicate an ancient burial mound (sídhe), which were believed to be portals to the Otherworld and the homes of ancestral gods.[11] He believes the mound was made as a platform on which druids would perform ceremonies and on which kings would be crowned, while drawing power and authority from the gods and ancestors.[13]

It is possible that each part of the monument represents something. The stones inside the wooden structure may represent souls in the house of the dead,[7] or the souls of fallen warriors in their equivalent of Valhalla.[11] Another theory is that the monument symbolizes a union of the three main classes of society: druids (the wooden frame), warriors (the stones) and farmers (the soil).[11] The central pillar could also represent the world pillar or world tree linking the sky, the earth and the underworld.[11] The radial pattern of the stone cairn may represent the sun wheel, a symbol associated with Celtic sun or sky deities.[11]

Dr Lynn writes: "It seems reasonable to suggest that, in the beginning of the first century BC, Navan was an otherworld place, the home of the gods and goddesses. It was a Celtic tribe's sanctuary, its capitol, its sacred symbol of sovereignty and cohesion".[11]

A recent study used remote sensing (including lidar, photogrammatry, and magnetic gradiometry) to map the site, and found evidence of Iron Age and medieval buildings underground, which co-author Patrick Gleeson says suggests that Navan Fort was "an incredibly important religious center and a place of paramount sacral and cultural authority in later prehistory".[14][15]

In Irish mythology

.JPG.webp)

In the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology, Emain Macha is the royal capital of the Ulaidh, the people who gave their name to the province of Ulster. It is the residence of Conchobar mac Nessa, king of Ulster. He is said to have had a warrior training school at Emain.[16] Conchobar's great hall at Emain was called by medieval writers in Chraebruad (the red-branched or red-poled edifice), and his royal warriors are named the Red Branch Knights in English translations.[17]

Emain Macha is said to have been named after Macha, who is believed to have been a sovereignty goddess of the Ulaidh.[18] One tale says that Macha, queen of the Ulaidh, forced her enemy's sons to dig the great bank-and-ditch after marking it out with her neck-brooch (eomuin), hence the name.[18] In another tale, Macha is the fairy wife of Crunnchu. Despite promising not to speak of her, Crunnchu boasts that his wife can outrun the king's horses. The king forces the pregnant Macha to race the horses. She wins, but then gives birth to twins on the finish line. Before dying in childbirth, she curses the Ulstermen to be overcome with the exhaustion of childbirth at the time of their greatest need. This is a fore-tale of the Táin Bó Cúailnge (Cattle Raid of Cooley). The name Emain Macha is thus explained as "Macha's twins".[18]

The Annals of the Four Masters says that the Three Collas conquered the area in 331 AD, burning Emain Macha and driving the Ulaidh eastwards over the River Bann. Another tradition is that Emain Macha was destroyed by Niall of the Nine Hostages, or his sons, in the following century.[19]

Many other characters from Irish mythology are associated with Emain Macha, including:

- Amergin the poet

- Cú Chulainn, the great warrior

- Emer, his strong-willed and beautiful bride

- Conall Cernach, his foster-brother and close friend

- Lóegaire, another warrior

- Cathbad, the chief druid

- Fergus mac Róich, another great warrior and king

- Deirdre of the Sorrows, and Naoise, her brave lover

- Leabharcham, the wise woman

Conservation and tourism

Until 1985, the site was threatened by the growth of a nearby limestone quarry. Due mostly to the efforts of the activist group Friends of Navan, a public inquiry held that year halted further quarrying, and recommended that Navan be developed for tourism. A visitor centre, featuring artefacts and audio-visual exhibitions, was opened in 1993, but closed in 2001 for lack of funds.[20] It reopened in 2005 after the site was bought by Armagh City and District Council.

Other significant prehistoric sites nearby include Haughey's Fort, an earlier Bronze Age hill fort two-thirds of a mile (1 km) to the west; the King's Stables, a manmade pool also dating to the Bronze Age; and Loughnashade, a natural lake which has yielded Iron Age artefacts.

In popular culture

Eamhain Mhacha is the name of an Irish traditional music group formed in 2008.[21] Irish heavy metal band Waylander also has a song called "Emain Macha" on their 1998 album Reawakening Pride Once Lost.

"Emain Macha" is the name of a place in the computer games Dark Age of Camelot,[22] Mabinogi and The Bard's Tale.

See also

- An sluagh sidhe so i nEamhuin? ("Is this a fairy host in Eamhain Mhacha?") – an Irish poem dated to the late 16th century.

References

- MacKillop, James (2004). A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860967-4.

- Newman, Conor. "The making of a royal site in early Ireland". The Past in the Past: the Re-use of Ancient Monuments. Edited by Richard Bradley & Howard Williams. Routledge, 1998. p.139

- Warner, Richard (2013). "Ptolemy's Isamnion promontory: rehabilitation and identification". Emania – Bulletin of the Navan Research Group, Issue 21. pp.21-29

- Navan, Co Armagh. PlaceNamesNI.

- "Navan Fort" (PDF). Environment and Heritage Service NI – State Care Historic Monuments. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- Andy Halpin & Conor Newman. Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press, 2006. pp.95-98

- "A Barbary Ape Skull from Navan Fort, Co. Armagh". Irish Archaeology. 19 May 2014.

- A New History of Ireland, Vol 1. Oxford University Press, 2005. p.167

- James Patrick Mallory, David Brown & Mike Baillie (1999). "Dating Navan Fort". Antiquity, Volume 73, Issue 280. pp.427-431

- Lynn, Chris. "Navan Fort: Home of Gods and Goddesses?". Archaeology Ireland, Volume 7, Issue 1. 1993. pp.17-21

- Mallory, James Patrick (2002). "Recent excavations and speculations on the Navan complex". Antiquity, Volume 76, Issue 292. pp.532-541

- Warner, Richard (2000). "Keeping out the Otherworld: The internal ditch at Navan and other Iron Age hengiform enclosures". Emania – Bulletin of the Navan Research Group, Issue 18. pp.39-42

- Geggel, Laura (5 August 2020). "Massive ancient temple complex may lurk beneath famous Northern Ireland fort". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Gleeson P, Queen's University Belfast, Others, CitationNeeded (c. 2020). "Citation Needed". Citation Needed.

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (1991). Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition. Prentice Hall. p. 112.

- Ó hÓgáin, p.413

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (1991). Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition. Prentice Hall. pp. 284–285.

- Ring, Trudy (2013). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Northern Europe. Routledge. p. 56.

- Bender, Barabara (2001). "The Politics of the Past: Emain Macha (Navan), Northern Ireland". In Layton, Robert (ed.). Destruction and Conservation of Cultural Property. Routledge. pp. 199–209. ISBN 0-415-21695-8.

- "Reels at Fleadh Tullamore 2009". YouTube.

- Shadows Edge – DAOC – Emain – Dark Age of Camelot New Frontiers Map

- Hutton, R. (1991). Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. ISBN 978-063118946-6.

External links

- Navan Centre & Fort – Official site at Visit Armagh

- Navan Fort – information at Northern Ireland Environment Agency

- Navan Research Group – official website

- "High Hopes for NI Tourist Centre" (BBC News)

- BBC Timelines

- Environment and Heritage Service page on Navan Fort, with photos

- Geography in Action: Navan Fort Archived 18 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- The Mysterious Ritual at Emain Macha in 94BC