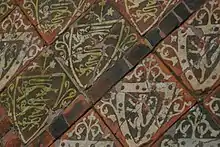

Encaustic tile

Encaustic tiles are ceramic tiles in which the pattern or figure on the surface is not a product of the glaze but of different colors of clay. They are usually of two colours but a tile may be composed of as many as six. The pattern appears inlaid into the body of the tile, so that the design remains as the tile is worn down.[1] Encaustic tiles may be glazed or unglazed and the inlay may be as shallow as 1⁄8 inch (3 mm), as is often the case with "printed" encaustic tile from the later medieval period, or as deep as a quarter inch.

History

.JPG.webp)

What were called encaustic tiles in the Victorian era were originally called inlaid tiles during the medieval period. The use of the word "encaustic" to describe an inlaid tile of two or more colors is linguistically incorrect. The word encaustic from Ancient Greek: ἐγκαυστικός means "burning in" from the ἐν en, "in" and καίειν kaiein, "to burn".[2] The term originally described a process of painting with a beeswax-based paint that was then fixed with heat.[3] It was also applied to a process of medieval enameling. The term did not come into use when describing tile until the nineteenth century. Supposedly, Victorians thought that the two colour tiles strongly resembled enamel work and so called them encaustic. Despite the error, the term has now been in common use for so long that it is an accepted name for inlaid tile work.

Encaustic or inlaid tiles enjoyed two periods of great popularity. The first came in the thirteenth century and lasted until Henry the Eighth's Protestant English Reformation in the sixteenth century which eschewed and removed much medieval church decoration along with the policy of the dissolution of the monasteries.

The second came when the tiles caught the attention of craftsmen during the Gothic Revival era, who after much trial and error mass-produced these tiles, and made them available to the general public. During both periods, tiles were made across Western Europe, though the centre of tile production was in England. Companies in the United States also made encaustic tile during the Gothic Revival architecture style's period. The American Encaustic Tiling Company of Zanesville, Ohio, was active until 1935.[4] However, in the 1930s, encaustic tiling began to lose ground to more affordable glass and vitreous glass tiles.[5]

Manufacture

Modern encaustic tiles use a two-shot moulding process. The 'inlay' colour is moulded first. For multiple colours, a mould with cavities for each colour is used and the individual colours are filled carefully. This coloured clay is then placed face-down in a mould that is backfilled with the body colour. The tiles are then fired.

The manufacture of encaustic clay tiles may be seen today at the Jackfield Tile Museum, one of the Ironbridge Gorge museums.[6]

Use

In both medieval times and in the nineteenth and twentieth century Gothic Revival, tiles were most often made for and laid in churches. Even tiles that were laid in private homes were often copies of those found in religious settings.[7] Encaustic tile floors exist all over Europe and North America, but are most prevalent in England where the greatest numbers of inlaid tiles were made.

See also

- Cement tile

- Jackfield Tile Museum – Museum of ceramic tile making, part of the Ironbridge Gorge

- American Encaustic Tiling Company

References

- "What Are Encaustic Tiles? – Channel4 – 4Homes". cementtile.vn. 2014. Retrieved 30 Oct 2014.

- "Encaustic – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". merriam-webster.com. 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "what is encaustic ? encaustic.co – home page". encaustic.co. 2012. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "tileheritage.org". tileheritage.org. 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Menhem, Chantal. "Encaustic Tiles: Finding Renewed Popularity". Mozaico. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- "Jackfield Tile Museum". Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.

- "Inform Guide – Ceramic Tiled Flooring – informguide-ceramicfloor.pdf" (PDF). pdf.js. 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

Bibliography

- Haberly, Loyd Mediaeval English Pavingtiles 1937