Endling

An endling is the last known individual of a species or subspecies. Once the endling dies, the species becomes extinct. The word was coined in correspondence in the scientific journal Nature.

Usage

The 4 April 1996 issue of Nature published a correspondence in which commentators suggested that a new word, endling, be adopted to denote the last individual of a species.[1][2] The 23 May issue of Nature published several counter-suggestions, including ender, terminarch, and relict.[1][3]

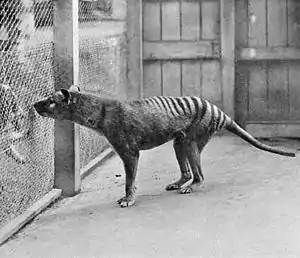

The word endling appeared on the walls of the National Museum of Australia in Tangled Destinies, a 2001 exhibition by Matt Kirchman and Scott Guerin, about the relationship between Australian peoples and their land. In the exhibition, the definition, as it appeared in Nature, was printed in large letters on the wall above two specimens of the extinct Tasmanian tiger: "Endling (n.) The last surviving individual of a species of animal or plant". A printed description of this exhibition offered a similar definition, omitting reference to plants: "An endling is the name given to an animal that is the last of its species."[4][5]

In The Flight of the Emu: A Hundred Years of Australian Ornithology 1901-2001, author Libby Robin stated that "the very last individual of a species" is "what scientists refer to as an 'endling'".[6]

In 2011, the word was used in the Earth Island Journal, in an essay by Eric Freedman entitled "Extinction Is Forever: A Quest for the Last Known Survivors". Freedman defined endling as "the last known specimen of her species."[7]

In "The Sense of an Endling", author Helen Lewis describes the notion of an endling as poignant, and the word as "wonderfully Tolkien-esque".[8]

Author Eric Freedman describes endling as "a word with finality", stating, "It is deep-to-the-bone chilling to know the exact date a species disappeared from Earth. It is even more ghastly to look upon the place where it happened and know that nobody knew or cared at the time what had transpired and why."[9]

Notable endlings

This is not a comprehensive list of contemporary extinction, but a list of high-profile, widely publicised examples of when the last individual of a species was known.

Birds

- The passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) became extinct at 1 p.m. on 1 September 1914 with the death of Martha, the last surviving member of the species, at the Cincinnati Zoo.[10][11]

- Incas, the last known Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), died, also at the Cincinnati Zoo, on 21 February 1918.[11] The species was officially declared extinct in 1939.

- Booming Ben, a solitary heath hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido), was last seen 11 March 1932 on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts.[12]

- Orange Band was the last known dusky seaside sparrow (Ammodramus maritumus nigrescens), who died on 17 June 1987 at the Discovery Island zoological park at Walt Disney World Resort.[13]

Mammals

- In 1627, the last aurochs, an ancestor of bovine and cattle, died in a forest near what is now Jaktorów in modern-day Poland.[14]

- The quagga (Equus quagga quagga) became extinct in the wild in the late 1870s due to hunting for meat and skins, and the subspecies' endling died in captivity on 12 August 1883 at the Artis in Amsterdam.[15]

- On 7 September 1936, the last known thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), also called the Tasmanian tiger, died in Hobart Zoo, after the species was hunted to extinction by farmers. It has been suggested this individual, a female later erroneously called "Benjamin",[16] died of neglect during a night of unusually extreme weather conditions.[17] It was also the last living individual of the family Thylacinidae.

- Celia, the last Pyrenean ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), was found dead on 6 January 2000 in the Spanish Pyrenees, after hunting and competition from livestock reduced the population to one individual.[18]

Reptiles and amphibians

.jpg.webp)

- On 24 June 2012, Lonesome George, the last known Pinta Island tortoise (Chelonoidis niger abingdonii), died in his habitat in the Galápagos Islands.[19]

- Until September 26, 2016, the Atlanta Botanical Garden was home to the last known surviving Rabbs' fringe-limbed treefrog (Ecnomiohyla rabborum) named "Toughie".[20]

- After being considered possibly extinct for 113 years, a Fernandina Island Galápagos tortoise was found in 2019. However, this female is the only confirmed individual.[21]

Invertebrates

- Turgi was the last Partula turgida, a Polynesian tree snail, who died on 31 January 1996 in the London Zoo.[22]

- A tank in the Bristol Zoo was the last refuge of Partula faba, a land snail from Ra'iātea in French Polynesia. The population dropped from 38 in 2012[23] to one in 2015.[24] The last individual died on 21 February 2016.[24]

- George was the last known individual of the Oahu tree snail species Achatinella apexfulva. It died on January 1, 2019, in captivity near Kailua, Hawaii.[25]

Plants

- The Curepipe Botanic Gardens in Mauritius have housed the last specimen of the palm Hyophorbe amaricaulis since the 1950s.[26]

- Pennantia baylisiana has only ever been known from one wild tree that still lives today.[27] Subsequent trees were cloned, but since 1985 hundreds of trees have been propagated by self-pollination.[28]

- Only one individual of the Wood's cycad (Encephalartos woodii) has existed since it was discovered in 1895, all examples being clones of this single male individual.[29]

- Only one living specimen of the tree species Madhuca diplostemon is known to exist.[30]

See also

- Anthropocene

- Conservation status

- De-extinction

- Extinction

- Frozen zoo (some store genetic material from endlings)

- Holocene extinction

- Lists of extinct animals

- List of neologisms

- Rare species

- Terminal speaker

References

- Jorgensen, Dolly (13 April 2013). "Naming and claiming the last". Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- Robert M. Webster; Bruce Erickson (4 April 1996). "The last word?". Nature. 380 (386): 386. Bibcode:1996Natur.380..386W. doi:10.1038/380386c0. PMID 8602235.

- Elaine Andrews (4 April 1996). "The last word". Nature. 381 (272): 272. Bibcode:1996Natur.381..272A. doi:10.1038/381272d0. S2CID 39305151.

- "Tangled Destinies" (PDF). National Museum of Australia. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Smith, Mike (2001). "The Endling exhibition, Tangled Destinies gallery, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2001" (PDF). National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Robin, Libby (2002). The Flight of the Emu: A Hundred Years of Australian Ornithology 1901-2001. Melbourne University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0522849875.

- Freedman, Eric (2011). "Extinction is Forever: A Quest for the Last Known Survivors". Earth Island Journal. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Lewis, Helen (27 June 2012). "The Sense of an Endling". The New Statesman. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Freedman, Eric (5 July 2008). "Cut from history: An abandoned Tasmanian zoo tells the haunting tale of an ending". EJ Magazine. Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- "Endangered Species Handbook". Animal Welfare Institute. 1983. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Blythe, Anne (27 August 2012). "Extinct Carolina Parakeet still fascinates". www.newsobserver.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "Heath Hen (Extinct)". BeautyOfBirds (formerly Avian Web). Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "Last of dusky sparrows dies". The New York Times. Associated Press. 17 June 1987.

- Rokosz, M. (1995). "History of the Aurochs (Bos taurus primigenius) in Poland" (PDF). Animal Genetics Resources Information. 16: 5–12. doi:10.1017/S1014233900004582. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- Van Bruggen, A.C. (1959). "Illustrated notes on some extinct South African ungulates". South African Journal of Science. 55 (8): 197–200. hdl:10520/AJA00382353_1382.

- Dunlevie, James (6 December, 2022). Stop calling the last thylacine Benjamin, Tasmanian tiger researcher says, ABC News. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- Lewis, Robert; Arnold, David (2002). Tangled Destinies: Exploring land and people in Australia over time through the National Museum of Australia (PDF). Ryebuck Media Pty, Limited. ISBN 0-949380-41-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20.

- Richard Gray and Roger Dobson (31 January 2009). "Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 August 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Valencia, Alexandra; Garcia, Eduardo (24 June 2012). "Lonesome George, last-of-his-kind Galapagos tortoise, dies". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2012-06-27.

- Bo Emerson (28 September 2016). "Rare frog goes extinct, despite Atlanta's rescue efforts". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- "Tortoise thought to be extinct for 113 years has been rediscovered on the Galapagos". Fox News. 2019-02-20.

- "Tiny Tree Snail Finally Creeps To Extinction". Chicago Tribune. 1 February 1996.

- Five of the world's 10 most at-risk species at Bristol Zoo

- "Captain Cook's bean snail Partula faba". islandbiodiversity.com. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

- Ed Yong (2019) "The Last of Its Kind" The Atlantic, July 2019. Accessed June 28, 2019.

- Bachraz, V. (TPTNC).; Strahm, W. (2000). "Hyophorbe amaricaulis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000: e.T38578A10125958. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T38578A10125958.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- de Lange, P. (2014). "Pennantia baylisiana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T30481A62768931. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-2.RLTS.T30481A62768931.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Platt, John (20 April 2010). "World's rarest tree gets some help". Scientific American. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- Bösenberg, J.D. (2020). "Encephalartos woodii". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T41881A51057496.en. Retrieved 2022-07-31.

- Rajwi, Tiki (2020-10-03). "Extinct tree found after 180 years in Kollam grove". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

External links

- What Do You Call the Last of a Species? by Michelle Nijhuis for The New Yorker

- Cut from history by Eric Freedman for Knight Center for Environmental Journalism

- Bringing Them Back to Life Archived 2013-04-11 at the Wayback Machine by Carl Zimmer for National Geographic Magazine.