Endymion (play)

Endymion, the Man in the Moon is an Elizabethan era comedy by John Lyly, written circa 1588.[1] The action of the play centers around a young courtier, Endymion, who is sent into an endless slumber by Tellus, his former lover, because he has spurned her to worship the ageless Queen Cynthia. The prose is characterised by Euphuism, Lyly's highly ornate, formalised style, meant to convey the intelligence and wit of the speaker. Endymion has been called "without doubt, the boldest in conception and the most beautiful in execution of all Lyly's plays."[2] Lyly makes allusions to ancient Greek and Roman texts and traditional English folklore throughout the play. While the title and characters are references to the myth of Endymion, the plot sharply deviates from the classical story and highlights contemporary issues in Elizabeth I's court through its allegorical framework.

Characters

- Endymion- a young man

- Cynthia- the queen

- Eumenides- Endymion's friend

- Tellus- lady-in-waiting at Cynthia's court

- Semele- lady-in-waiting

- Floscula- Tellus's servant

- Dares- Endymion's page

- Samias- Eumenides' page

- Sir Tophas- a knight

- Epiton- Sir Tophas' page

- Dipsas- aged sorceress who bewitches Endymion for Tellus

- Bagoa- a sorceress, assistant to Dipsas

- Geron- old man, Dipsas's estranged husband

- Corsites – a captain

- Pythagoras- Greek philosopher

- Gyptes- Egyptian soothsayer

- Scintilla- maid-in-waiting

- Flavilla- maid-in-waiting

- Zontes- Nobleman at court, sent to Greece

- Panelion- Nobleman at court, sent to Egypt

- Three ladies and an old man, in a dumbshow

- Fairies

Plot

Prologue

The play begins with a prologue originally created for a performance before Queen Elizabeth I. It asks the audience to excuse anything that might be seen as foolish fancy and asserts the fiction of the narrative.[3]

Act i

Eumenides is seriously concerned that his friend has gone mad. Endymion is raving about being in love with the moon. After pushing him, Endymion clarifies he is in love with Cynthia. Eumenides is astonished at Endymion's ebullient proclamations of love—he decides his friend is bewitched and needs to be closely watched.

Tellus and Floscula have a parallel conversation about Endymion; he has pivoted away from Tellus in his growing obsession with the Queen. Tellus is distraught, but Floscula warns her mistress that the cause is hopeless, and if she compares herself to Cynthia, she would give up "being between you and her no comparison" (I.ii.18). She should instead "wonder than rage at the greatness of [Endymion's] mind, being affected with a thing more than mortal" (I.ii.19). She then warns Tellus that Cynthia's power is absolute, and advises her to leave Endymion to his new love. Tellus becomes enraged and announces her intentions to avenge herself on Endymion. In the final scene of this act, Tellus meets with Dipsas, the sorceress, who explains that while she cannot "rule hearts" (I.iv.27), she can make Endymion's love less ardent, but only for a little while.

In the meantime, Sir Tophas—a pompous, foolish knight—provides comic relief in a witty repartee with the pages of Endymion and Eumenides.

Act ii

Tellus confronts Endymion. In their conversation, she forces him to admit that his love for her has waned, and that he now loves Cynthia. Tellus mentions here that Cynthia is an unchanging virgin queen, a woman (not an immortal goddess). She is like "Vesta" and "Venus," but Endymion explains, ". . .Immortal? . . . No, but incomparable" (II.i.89–98). After the two former lovers part, Dipsas and her assistant, Bagoa, secretly follow Endymion and listen as he laments his love of the unattainable Cynthia as well as regrets over his dismissal of the worthy Tellus. Endymion eventually falls asleep, and Dipsas then bewitches his slumber so that he will not wake.

Immediately after this scene, a dumbshow is performed in which three ladies enter, one makes as though to kill Endymion, but is stopped. Then, an old man enters with a book; he offers it three times to Endymion, who refuses twice and takes it on the third attempt. This scene is explained as a dream sequence at the end of the play.

Act iii

Cynthia learns of Endymion's sleep. She discusses this with Eumenides, Tellus, Semele, and three other lords (Corsites, Zontes, and Panelion). During this conversation, Tellus offends Cynthia by contradicting her judgement of Endymion. Cynthia commands Corsites to remove Tellus from the court and hold her captive. While following this command, however, Corsites falls in love with Tellus. Cynthia sends Eumenides, Zantes and Panelion to Thessaly, Greece, and Egypt to find a cure for Endymion. In Thessaly, Eumenides finds a magic fountain that shows him how to save his friend.

Sir Tophas again appears and now proclaims his love for the hideous sorceress, Dipsas, whose decrepit body and unfavorable nature make her a perfect match in his eyes.

Act iv

The final acts of the play appear to occur after a span of 20–40 years—the entire time that Endymion sleeps.

Tellus remains imprisoned and is required to weave a giant tapestry. Taking advantage of Corsites' love for her, she convinces him to go to Endymion and bring him back to her. When Corsites goes to Endymion, he finds that it is impossible to lift or move the sleeping body. He does, however, call up four wrathful fairies who pinch and torture him for touching Endymion. The fairies chase him offstage, and Cynthia enters, accompanied by the lords Zontes and Panelion, returned from Greece and Egypt. To aid the Queen, Zontes has brought Pythagoras, the mathematician and philosopher, and Panelion has brought a soothsayer named Gyptes. Corsites returns, covered in welts, and explains that Tellus tricked him.

The scene ends with both Gyptes and Pythagoras thwarted by Endymion's spell—they believe that until the witch responsible dies, nothing can be done.

Act v

Eumenides finally returns with information: Cynthia must kiss the sleeping man and he will awaken. The prophecy works, and Endymion comes back to life, though he has aged significantly. He initially barely recognises anyone except for Cynthia. It is later revealed that Bagoa has told the court of Dipsas and Tellus' plot against Endymion, and the sorceress has turned her into a tree in revenge.

Dipsas and Tellus are exposed for their malicious actions and called to account. Tellus begs forgiveness and explains that Endymion's wavering love made her so unhappy that she became mad. Dipsas says that she regrets bewitching Endymion over all her other misdeeds. Endymion explains that his feelings for Cynthia are chaste and sanctified—no one is higher in his affection—but he does not love her romantically. In response, Cynthia grants him her favour, and this blessing transforms him back into a young man. Because Endymion is restored, Tellus is forgiven, and she happily agrees to marry Corsites (who still loves her). Semele and Eumenides are coupled, and Dipsas repents—she returns to her estranged husband Geron and promises to abandon witchcraft. Cynthia tells Bagoa, still a tree, to become human, and she is also restored through the magic of Cynthia's command. All follow Cynthia offstage, and all seems happily resolved.

Epilogue

The final section of the play contains a fable about "A man walking abroad" and two elements competing for "sovereignty" over him in a show of strength: the wind tries to tear the man's coat from his body, while the sun simply warms him, and he voluntarily removes the coat (epilogue.1–10). Lyly's fable, like the prologue, is a direct address to Queen Elizabeth, and suggests that control is gained more easily with warmth than with violence. The next lines explain,

Dread sovereign, the malicious that seek to overthrow us with threats do but stiffen our thoughts . . . But if your Highness vouchsafe with your favorable beams to glance upon us, we shall not only stoop, but with all humility lay both our hands and hearts at your feet. (Epilogue. 11–15).

This directly applies the narrative of the fable to the behaviour of the queen it addresses, and suggests that the action of the play is also intended for her education and benefit.

Although the main plotline is that of Endymion and Cynthia, there are multiple romantic subplots involving Eumenides and Semele, Corsites and Tellus, and a comic subplot with Sir Tophas, who falls in love with the enchantress Dipsas. Sir Tophas is the butt of the jokes and pranks of the crew of pages that constitute a standard feature of Lyly's drama.[4]

Performance and publication

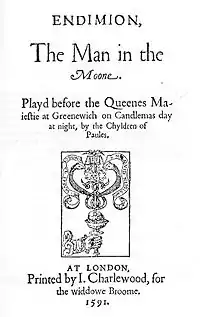

It is not known with certainty when Lyly wrote Endymion, but it was first performed by the Children of Paul's at Greenwich Palace in 1588, on Candlemas (2 February), before Queen Elizabeth I.[5] Endymion was entered into the Stationers' Register on 4 October 1591, and was first published soon after in a quarto printed by John Charlwood for Joan Broome (the widow of bookseller William Broome, who had published reprints of Lyly's Campaspe and Sapho and Phao earlier in 1591). It was published again in Six Court Comedies (1632), the first collected edition of Lyly's plays issued by Edward Blount.

Endymion's production calls for multiple props and stage magic, such as the magic fountain, the lunary bank where Endymion spends his magical sleep, and tree that could change its shape.[6]

Endymion is currently in a state of revival. The 2009 American Shakespeare Center's Young Company produced the first Original Staging Practices production of Endymion, under the direction of Brett Sullivan Santry, in an estimated 400 years. While the script was shortened, the performance included a cast of noteworthy young American actors including; Ben Lauer as Endymion, Mary Margaret Watkins as Cynthia, and Mariah Webb as Tellus.

A 2012 full production by the T24 Drama Society of the University of Kent took place, directed by Freddy Waller and starring John Davis as Endymion and Holly Morran as Cynthia.[7]

The play was performed alongside Lyly's Gallathea in February 2018 by students of the Shakespeare & Performance graduate program at Mary Baldwin University in the American Shakespeare Center's Blackfriars Playhouse.

Sources

As the title indicates, the play references the mythical story of Endymion, but the narrative deviates sharply; the work is a product of the culture in which it was created, and does not seem bound to any historical precedence. This change in plot, however, poses Cynthia as a chaste allegorical model for Queen Elizabeth, who was often represented as a moon goddess in popular imagery.[8] Lyly also seems to have borrowed some hints from the dialogue between the Moon and Venus written by Lucian. Elements in the comic subplot derive from the Italian Commedia dell'arte and the classical Latin comedy of Plautus and Terence.[9]

Critical response

It is widely recognised that Endymion is to a large extent allegorical, with Cynthia representing Queen Elizabeth I. Nineteenth-century critics tended to assign other roles in the play to historical figures of Elizabeth's court: Endymion, perhaps, was Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, while Tellus was Mary, Queen of Scots.[10] Twentieth-century critics have approached these hypotheses sceptically, arguing that if Lyly had ventured any such bold or obvious commentary on Elizabeth's personal life, his career at Court would have ended quickly.[11] Alongside these courtly interpretations, an overtly Christian reading of the allegory has been advocated.[12] From a religious instead of a political angle, Cynthia would represent holy and pure aspirations while Tellus, whose name means "earth" in Latin, would represent worldly desires. Endymion's conflicts between Tellus and Cynthia would be, in this sense, an allegory for the "struggle between fleshly temptation and heavenly contemplation" that all Christians must face.[13]

It is generally agreed that Endymion is the one of Lyly's plays that had the strongest influence on Shakespeare, most obviously on Love's Labor's Lost and A Midsummer Night's Dream.[14] The multiple subplots in Endymion may have inspired Shakespeare's use of comic subplots and clown characters in his own plays, such as Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night.[4]

Endymion is light on characterisation but verbally rich. In the view of one commentator, the play, "with its radiating central image, its mathematical elaboration, its receding depths, its near motionless and queer timelessness," is "more a contemplation than a comedy."[15]

References

- Bevington, David (1996). "Introduction: Date and Authorship". In Bevington, David M. (ed.). Endymion. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 9780719030918. OCLC 45265821.

- Wilson, John Dover. John Lyly. Cambridge, Macmillan and Bowes, 1905; p. 107.

- Lyly, John (1997) [1588]. Endymion. Bevington, David M. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780719030918. OCLC 45265821.

- Bevington, David; Engle, Lars; Maus, Katharine Eisaman; Rasmussen, Eric, eds. (2002). English Renaissance Drama: A Norton Anthology. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 78. ISBN 0-393-97655-6.

- Kiefer, Frederick (2015). English Drama from Everyman to 1660: Performance and Print. Tempe, Arizona: ACRMS (Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies). p. 168. ISBN 978-0-86698-494-2.

- Kiefer 2015, p. 169.

- "Students give rare performance of Elizabethan play by Canterbury-born John Lyly - News, press and media - University of Kent". www.kent.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- Walker 2014, p. 509.

- Boughner, Daniel C. "The Background of Lyly's Tophas." Papers of the Modern Language Association 54 (1939), pp. 967–73.

- Wilson, p. 109.

- Chambers, Vol. 3, p. 415.

- Bryant, John A., Jr. "The Nature of the Allegory in Lyly's Endymion." Renaissance Papers (1956), pp. 4–11.

- Bevington, et al. 2002, pp. 75–76.

- Wilson, pp. 109–10.

- Peter Saccio, quoted in: Terence P. Logan and Denzell S. Smith, eds. The Predecessors of Shakespeare: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1973; p. 132.