Energy economics

Energy economics is a broad scientific subject area which includes topics related to supply and use of energy in societies.[1] Considering the cost of energy services and associated value gives economic meaning to the efficiency at which energy can be produced.[2] Energy services can be defined as functions that generate and provide energy to the “desired end services or states”.[3] The efficiency of energy services is dependent on the engineered technology used to produce and supply energy. The goal is to minimise energy input required (e.g. kWh, mJ, see Units of Energy) to produce the energy service, such as lighting (lumens), heating (temperature) and fuel (natural gas). The main sectors considered in energy economics are transportation and building, although it is relevant to a broad scale of human activities, including households and businesses at a microeconomic level and resource management and environmental impacts at a macroeconomic level.

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

History

Energy related issues have been actively present in economic literature since the 1973 oil crisis, but have their roots much further back in the history. As early as 1865, W.S. Jevons expressed his concern about the eventual depletion of coal resources in his book The Coal Question. One of the best known early attempts to work on the economics of exhaustible resources (incl. fossil fuel) was made by H. Hotelling, who derived a price path for non-renewable resources, known as Hotelling's rule.[4]

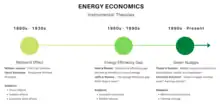

Development of energy economics theory over the last two centuries can be attributed to three main economic subjects – the rebound effect, the energy efficiency gap and more recently, 'green nudges'.

The Rebound Effect (1860s to 1930s)

While energy efficiency is improved with new technology, expected energy savings are less-than proportional to the efficiency gains due to behavioural responses.[5] There are three behavioural sub-theories to be considered: the direct rebound effect, which anticipates increased use of the energy service that was improved; the indirect rebound effect, which considers an increased income effect created by savings then allowing for increased energy consumption, and; the economy-wide effect, which results from an increase in energy prices due to the newly developed technology improvements.[6]

The Energy Efficiency Gap (1980s to 1990s)

Suboptimal investment in improvement of energy efficiency resulting from market failures/barriers prevents the optimal use of energy.[7] From an economical standpoint, a rational decision-maker with perfect information will optimally choose between the trade-off of initial investment and energy costs. However, due to uncertainties such as environmental externalities, the optimal potential energy efficiency is not always able to be achieved, thus creating an energy efficiency gap.

Green Nudges (1990s to Current)

While the energy efficiency gap considers economical investments, it does not consider behavioural anomalies in energy consumers. Growing concerns surrounding climate change and other environmental impacts have led to what economists would describe as irrational behaviours being exhibited by energy consumers. A contribution to this has been government interventions, coined "green nudges’ by Thaler and Sustein (2008),[8] such as feedback on energy bills. Now that it is realised people do not behave rationally, research into energy economics is more focused on behaviours and impacting decision-making to close the energy efficiency gap.[5]

Economic factors

Due to diversity of issues and methods applied and shared with a number of academic disciplines, energy economics does not present itself as a self-contained academic discipline, but it is an applied subdiscipline of economics. From the list of main topics of economics, some relate strongly to energy economics:

Energy economics also draws heavily on results of energy engineering, geology, political sciences, ecology etc. Recent focus of energy economics includes the following issues:

- Climate change and climate policy

- Demand response

- Elasticity of supply and demand in energy market

- Energy and economic growth

- Energy derivatives

- Energy elasticity

- Energy forecasting

- Energy markets and electricity markets - liberalisation, (de- or re-) regulation

- energy infrastructure

- Environmental policy

- Sustainability

Some institutions of higher education (universities) recognise energy economics as a viable career opportunity, offering this as a curriculum. The University of Cambridge, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam are the top three research universities, and Resources for the Future the top research institute.[9] There are numerous other research departments, companies, and professionals offering energy economics studies and consultations.

Sources, links and portals

Leading journals of energy economics include:

There are several other journals that regularly publish papers in energy economics:

- Energy – The International Journal

- Energy Policy

- International Journal of Global Energy Issues

- Journal of Energy Markets

- Utilities Policy

Much progress in energy economics has been made through the conferences of the International Association for Energy Economics, the model comparison exercises of the (Stanford) Energy Modeling Forum and the meetings of the International Energy Workshop.

IDEAS/RePEc has a collection of recent working papers.[10]

Leading energy economists

The top 20 leading energy economists as of December 2016 are:[11]

- Martin L. Weitzman

- Lutz Kilian

- Robert S. Pindyck

- David M. Newbery

- Kenneth J. Arrow

- Richard S.J. Tol

- Severin Borenstein

- Richard G. Newell

- Frederick (Rick) van der Ploeg

- Michael Greenstone

- Richard Schmalensee

- James Hamilton

- Robert Norman Stavins

- Ilhan Ozturk

- Paul Joskow

- Ramazan Sari

- Jeffrey A. Frankel

- David Ian Stern

- Kenneth S. Rogoff

- Rafal Weron

- Michael Gerald Pollitt

- Ugur Soytas

See also

- Energy economists (category)

- Cost of electricity by source

- Ecological economics

- Embodied energy

- Energy accounting

- Energy & Environment

- Energy balance

- Energy policy

- Energy subsidy

- EROEI

- Industrial ecology

- International Energy Agency

- List of energy storage projects

- List of energy topics

- Social metabolism

- Sustainable energy

- Thermoeconomics

References

- Sickles, Robin (2008). "energy economics." The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

- Giraudet, Louis-Gaëtan; Missemer, Antoine (2019), The Economics of Energy Efficiency, a Historical Perspective, retrieved 2021-04-25

- Fell, Michael James (2017-05-01). "Energy services: A conceptual review". Energy Research & Social Science. 27: 129–140. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.02.010. ISSN 2214-6296.

- Hotelling, H. (1931). "The Economics of Exhaustible Resources". Journal of Political Economy. 39 (2): 137–175. doi:10.1086/254195. JSTOR 1822328. S2CID 44026808.

- Giraudet, Louis-Gaëtan; Missemer, Antoine (2019), The Economics of Energy Efficiency, a Historical Perspective, retrieved 2021-04-25

- Herring, Horace; Roy, Robin (2007-04-01). "Technological innovation, energy efficient design and the rebound effect". Technovation. 27 (4): 194–203. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2006.11.004. ISSN 0166-4972.

- Häckel, Björn; Pfosser, Stefan; Tränkler, Timm (2017-12-01). "Explaining the energy efficiency gap - Expected Utility Theory versus Cumulative Prospect Theory". Energy Policy. 111: 414–426. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.09.026. ISSN 0301-4215.

- Thaler, Richard; Sunstein, Cass (2009). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Camberwell, Vic.: Penguin Group Australia. ISBN 9780141040011.

- "Economics Field Rankings: Energy Economics - IDEAS/RePEc". ideas.repec.org.

- "NEP-ENE: New economic research on Energy Economics | IDEAS/RePEc".

- IDEAS/RePEc has a list of energy economists and a ranking of the same.

Further reading

- How to Measure the True Cost of Fossil Fuels March 30, 2013 Scientific American

- Bhattacharyya, S. (2011). Energy Economics: Concepts, Issues, Markets, and Governance. London: Springer-Verlag limited.

- Herberg, Mikkal (2014). Energy Security and the Asia-Pacific: Course Reader. United States: The National Bureau of Asian Research.

- Zweifel, P., Praktiknjo, A., Erdmann, G. (2017). Energy Economics - Theory and Applications. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.